APA style and citations for dummies - Joe Giampalmi 2021

Revising: why rewriting is so important

Covering all bases: three-level revising

Earning applause: APA writing for the academic audience

IN THIS CHAPTER

Modeling revision practices of best writers

Rethinking the big picture

Pruning paragraphs and sentences

Searching for precise words

Systematic revising, the motherboard of academic and career writing success, offers an opportunity to transition writing from good to great, to restructure a C-paper into an A-paper.

Writing professors generally agree that their best writers are their best rewriters. Successful writing results from major revisions of second, third, and sometimes fourth drafts. During these revisions, a shift happens as writers revise at the structural level, paragraph and sentence levels, and word level. Writers show improvement from draft to draft as they also fulfill a multi-draft requirement of many university first-year-writing programs.

APA recognizes the importance of revising manuscripts, saying, “Most manuscripts need to be revised….” This advice applies to all serious writing. (You decide the seriousness of your texting, emailing, and social posting.)

In this chapter, I guide you through an organized revision plan from a global approach through to a local approach. You see an improvement in your writing as you organize your argument, tighten your paragraph and sentence structure, and choose precise words. If you commit to revising every time you write, you’ll see your writing improve with every new project.

![]() Don’t equate revising with editing. Editing is like throwing a ball with a friend; revising is like teaching your dog to catch a ball. Editing and proofreading, lower-order skills, involve the correction of spelling, grammar, punctuation, and usage — mechanical skills that improve readability. Revising, a higher-order skill, is the recursive process of rethinking, ’re-visioning’, and rewriting.

Don’t equate revising with editing. Editing is like throwing a ball with a friend; revising is like teaching your dog to catch a ball. Editing and proofreading, lower-order skills, involve the correction of spelling, grammar, punctuation, and usage — mechanical skills that improve readability. Revising, a higher-order skill, is the recursive process of rethinking, ’re-visioning’, and rewriting.

Heading to the operating room: time to revise with “Major surgery”

“It is no sign of weakness or defeat that your manuscript ends up in need of major surgery. This is common in all writing and among the best of writers,” said E. B. White (1899—1985), author of Charlotte’s Web and co-author of the iconic The Elements of Style. White emphasizes that “the best of writers” revise with “major surgery.” Other legendary writers who promote revising include

· Robert Graves, British poet and novelist (1895—1985): “There is no such thing as good writing. Only good rewriting.”

· Nora DeLoach, American mystery writer (1940—2001): “Writing is rewriting.”

· Mark Twain, American humorist (1835—1910): “A successful book is not made of what is in it, but of what is left out of it.”

· Patricia Reilly, American children’s literature author (b. 1935): “Revision is the heart of writing.”

· S. A. Bodeen, American young adult novelist (b. 1965): “It’s easier to revise lousy writing than to revise a blank sheet of paper.”

· Vladimir Nabokov, Russian-American novelist (1899—1977): “I have rewritten — often several times — every word I have ever published.”

· Robert Cormier, American author (1925—2000): “The beautiful part of writing is that you don't have to get it right the first time, unlike, say a brain surgeon. You can always do it better, find the exact word, the apt phrase, the leaping simile.”

· Judy Blume, American young adult author (b. 1938): “I'm a rewriter. That's the part I like best … once I have a pile of paper to work with, it's like having the pieces of a puzzle. I just have to put the pieces together to make a picture.”

· James Michener, American author (1907—1997): “I'm not a very good writer, but I'm an excellent rewriter.”

Revising: why rewriting is so important

A wise person once said only fools and dead people never change their minds. You’re neither a fool nor unable to revise your writing. Writers do change their minds. Successful writers have been revising since the invention of the eraser, which evolved into your deletion key. Revising is part of the creative process and common to the work of artists, architects, automakers, designers, and chefs — even spouses occasionally revise.

The goal of revising is improving performance. If the Wright brothers didn’t continuously revise and improve, the invention of flight would have been delayed. If famous writers lacked their passion to revise, many famous literary works of art would not exist.

The value of revising to you as an academic writer includes

· Improves structural organization

· Clarifies development of ideas

· Eliminates unnecessary and overused words

· Corrects inaccurate use of language conventions

Experienced professors can easily identify one-and-done writing projects that lack commitment to revising. Red flags of one-draft writing include

· An unbalanced pace of argument development

· A loosely structured argument that lacks tie-in to the focus

· A pattern of longer sentences with excessive afterthoughts

· Editing errors resulting from limited manuscript readings

· Patterns of clichés and informal language

· Wordiness resulting from a lack of feedback

· A grade that won’t please you

Revising may not have been a regular writing process strategy prior to college, but it’s necessary for successful college writing. Professors not only hold you more accountable for your writing ideas, but their preparation hours allow them more time to evaluate your writing content.

The following sections show you techniques for getting feedback and how to apply that feedback to sections of your paper.

Seeking feedback when revising

Quality revision begins with quality feedback. Your primary source of feedback is your professor. Your most effective professor feedback strategy is scheduling a conference to review your writing. Ask questions using the language of writing: organization, tone, focus, development, and opening and closing. As you become familiar with sources (see Chapter 11) and citations (refer to Chapter 10), ask questions about them. If you lack understanding of your professor’s comments, ask questions about how to address them. Keep your professor focused on the information you want. As you practice feedback and revising, you’ll develop self-feedback skills to complement feedback from others.

![]() In addition, cultivate a dependable, trusted peer as a feedback partner. Peer feedback research shows that the person giving the feedback improves writing more than the person receiving the feedback. You give feedback on a peer’s writing and you see a peer’s approach that addresses assignment issues. You’ll also follow your mom’s advice that giving is better than receiving.

In addition, cultivate a dependable, trusted peer as a feedback partner. Peer feedback research shows that the person giving the feedback improves writing more than the person receiving the feedback. You give feedback on a peer’s writing and you see a peer’s approach that addresses assignment issues. You’ll also follow your mom’s advice that giving is better than receiving.

A successful revising strategy demands a 24- to 36-hour separation from a previous draft. The interval frees data from the brain’s working memory, the most limited storage capacity of the brain. Another technique that frees memory is a short walk or run.

![]() Occasionally writers make false starts or experience writer’s block. A false start, like losing your appetite for an overpriced menu item, can result from too broad or too narrow an argument or the unavailability of research to support the argument. Before committing to a topic, ensure sufficient research is available. If you experience writer’s block or a temporary inability to create text, find another area of your project to continue with: revising, reading, researching, validating citations and references — something that progresses your paper. As you know, almost all college deadlines, like workplace deadlines, are set in stone. In many cases, asking your professor for a deadline extension is like telling your professor you mismanaged your time.

Occasionally writers make false starts or experience writer’s block. A false start, like losing your appetite for an overpriced menu item, can result from too broad or too narrow an argument or the unavailability of research to support the argument. Before committing to a topic, ensure sufficient research is available. If you experience writer’s block or a temporary inability to create text, find another area of your project to continue with: revising, reading, researching, validating citations and references — something that progresses your paper. As you know, almost all college deadlines, like workplace deadlines, are set in stone. In many cases, asking your professor for a deadline extension is like telling your professor you mismanaged your time.

Rewriting in action: A real-life example

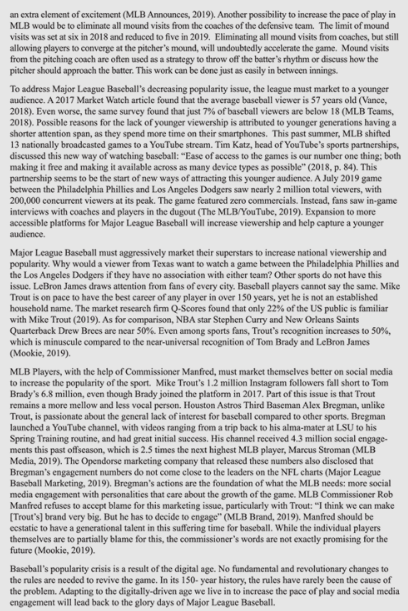

The following example (see Figure 8-1) of an unrevised college research paper was submitted by Grant Giampalmi, then a freshman at Boston College. The revision of the opening, middle, and closing appears in the sections that follow. The paper earned an A.

![]() Citations in this model have been fictionalized to avoid plagiarism, and the reference list is not included. Citations are detailed in Part 3. Note: The font sizes in the examples in this chapter aren’t in line with APA style. They’ve been sized for this book.

Citations in this model have been fictionalized to avoid plagiarism, and the reference list is not included. Citations are detailed in Part 3. Note: The font sizes in the examples in this chapter aren’t in line with APA style. They’ve been sized for this book.

FIGURE 8-1: An unrevised college research paper. Published with permission from Grant Giampalmi.