APA style and citations for dummies - Joe Giampalmi 2021

Developing lifetime literacy skills: reading for success

Achieving your personal best: student improvement plan

Earning applause: APA writing for the academic audience

You’ve achieved your academic success today because your family recognized the value of reading and teaching you reading skills at a young age. Studies show that successful readers are happier, healthier, and more economically secure. Reading on level by about fourth grade predicts academic and career success, regardless of socioeconomic background. Add if you need more evidence, readers make better choices of a significant other. Why do you think college libraries are so popular?

Reading to learn

Trying to educate yourself in college without reading is like trying to swim without water; oceans of knowledge are inaccessible. In addition to reading for pleasure, college students also read as their primary source of learning and absorbing information. Reading-to-learn strategies and content-specific approaches to engaging with information differ for nonfiction sources such as textbooks, research articles, technical materials, and math and science content. Intense content, such as that found in textbooks, requires a deliberate pace and frequent re-readings. I discuss these strategies in greater detail in the following sections.

Engaging with critical thinking skills

College reading not only requires that you learn and discover skills that are common to high school reading, but also that you engage with the following critical thinking skills:

· Applying: What other topics are similar to what you read? How is the topic applicable to current events, other books you are reading, topics in other courses, and your life in general?

· Questioning: What questions does the topic raise? Who or what is affected? …

· Evaluating: What are the topic’s assets and liabilities? Does it have more pluses than minuses? Is any part of the topic an outlier?

· Validating: Is the topic mainstream and generally accepted as believable? Is the publication source accepted as valid in the field?

· Speculating: How does the topic respond to what-if scenarios? What if the topic was relevant a hundred years ago, or will be relevant a hundred years in the future?

· Articulating: What one sentence clarifies the topic? Can that sentence be revised following the strategies discussed in Chapter 6?

· Synthesizing: How does this information fit into the big picture?

![]() You can develop your critical-thinking skills by responding to the following questions before, during, and after reading:

You can develop your critical-thinking skills by responding to the following questions before, during, and after reading:

· What are the author’s background (including financial affiliations), positions on the topic, and level of respectability within the field? Is the author considered mainstream or an outlier?

· Do the date and source of publication increase or decrease relevance to the topic?

· What did you learn from skimming titles, headings, subheadings, and figures? What information is revealed in the abstract, glossary, notes, or appendix?

· What do you identify as a purpose for reading? Why was the topic assigned? How does the reading align with course content?

· What background information do you know about the topic? What could you briefly read that provides additional background information? Do the citations and references add to this information?

· What’s a one-sentence summary that identifies what you learned from the reading?

· What books offer additional follow-up on the topic?

· What questions and clarifications need follow-up?

Read to live longer

Scientists have discovered that people who read novels live longer. Strategies for reading novels and similar fiction include the following:

· Skim a plot summary to familiarize yourself with the setting, plot, and characters. Also read a short background on the author, time period, and location.

· Recognize the focus, concentration, and attention to detail required to read the novel — which also represents your mental growth. Acclimation to the story may take 50 or more pages.

· Read with a pencil and record notes, questions, and clarifications. Draw diagrams to connect characters and ideas. Record page numbers for future reference. Frequently stop, think, and record thoughts. End a reading session at the end of a chapter. Capitalize on the author’s use of interpretation of events.

· Identify how the author’s use of literary devices (flashbacks, foreshadowing, symbolism, and repetition) applies to the plot or theme.

Talking to yourself: Annotation

Annotation, another read-to-learn strategy, is self-conversation where you discuss your reading. Like any conversation, reflecting increases learning. Sometimes called active reading, annotation creates connections among an author’s ideas. The purpose of annotation is to locate key information to recall and react to for class discussion and writing reference. Strategies for annotation include

· Identifying relationships among ideas

· Locating main and supporting points

· Paraphrasing main ideas using familiar words

· Identifying new vocabulary, terms, and concepts

· Applying, speculating, and questioning

![]() Highlighting lacks the effectiveness of annotating because it does not require handwriting, a brain-engaging activity. Annotating can be completed in book margins or by writing on sticky notes.

Highlighting lacks the effectiveness of annotating because it does not require handwriting, a brain-engaging activity. Annotating can be completed in book margins or by writing on sticky notes.

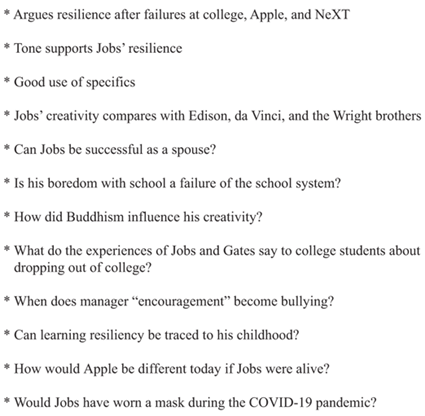

The following figure contains a sample paragraph.

Here is a sample annotation for this paragraph.

![]() Strategies to read textbooks

Strategies to read textbooks

Textbooks represent some of the most challenging materials you’ll be required to read, and frequently the most expensive, sometimes requiring a mortgage. However, like a house, textbooks represent a good investment, and many textbooks will be lifetime treasures. As you become more experienced with college academics, you’ll develop a sense of how to approach textbooks — like a gentle lamb or a ferocious lion, either reading for general ideas and concepts, or attacking it for facts and fundamentals. Read textbooks with the confidence that you can understand concepts. Textbook reading strategies include

· Reading the Preface to identify the author’s approach

· Previewing titles, headings, and other organizational aids

· Studying to align content with the type of text, such as fiction or nonfiction

· Creating and answering test questions

· Reading study questions at the end of a chapter, and previews at the beginning

· Explaining what you read to someone in your class

· Learning new vocabulary, terms, and concepts

· Reading at a slow pace and in small chunks

· Ending textbook sessions with notes and annotations for future review

A recent study identified the benefits of reading textbook chapters backward, beginning with study questions and working toward the front of the chapter.

Improving your reading plan

You may not be surprised to hear that not all college students work with the same intensity; some students approach academics like a lamb, and some like a lion. But in the world of higher education, lambs can become lions. If you’re a lamb — and your reading skills are producing grades lower than a B-level GPA — then you can transform into an academic lion by modeling the reading behaviors of your school’s best scholars.

With a few weekly hours committed to additional reading, you can become an academic predator, achieving higher reading proficiency, improving your performance in all courses, earning a higher GPA, and increasing your career and lifetime opportunities. The following sections discuss some strategies you can include in your reading improvement plan.

Be committed

To rule the reading jungle, schedule at least one 2-hour reading block every week. Logistics of that commitment include the following:

· Identifying your ideal time, location, and environment for scheduling reading sessions. Determine if your reading energy is highest in the morning, evening, or nighttime. Select a convenient location that motivates you — outdoors, near a window, or in a study room. Separate yourself from devices. Your social media empire won’t collapse in two hours.

· Creating a reading-session plan. Establish length and content goals for the reading you want to accomplish. Read the most challenging materials first. Annotate or summarize. Finish with a reading accountability strategy such as writing the purpose or application of the reading.

· Determining a reading purpose. Establish a reading purpose, in the form of a question, for each section you read.

![]() Begin every academic project with 30 minutes of background reading on the topic. Read for topic history, approaches, positions, relevancy, and implications.

Begin every academic project with 30 minutes of background reading on the topic. Read for topic history, approaches, positions, relevancy, and implications.

Incorporate reading in your everyday life

Long-term strategies (around your semester workload) to improve your college reading skills include

· Exploring a variety of formats and genres, such as poetry, plays, science fiction, short stories, biography, memoir, and technology

· Talking with people who read similar books or authors

· Browsing large bookstores and small local bookstores and searching for books on Amazon

· Researching topics that interest you, such as music genres, finance, languages, cooking, travel, and do-it-yourself skills

![]() In addition to academic reading, read for leisure about 30 minutes daily, which provides additional practice and information. Read current events, which can provide background and context for classroom discussion and writing.

In addition to academic reading, read for leisure about 30 minutes daily, which provides additional practice and information. Read current events, which can provide background and context for classroom discussion and writing.

Your daily functional reading will require another 30 minutes: directions, schedules, forms, signs, websites — anything college students need to navigate through their day. As you read, reflect, speculate, evaluate, and apply.

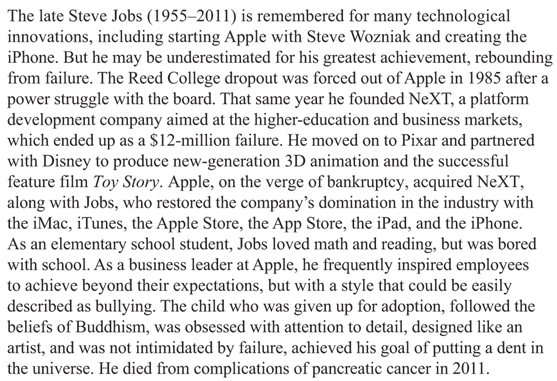

Read like Steve Jobs

The late Steve Jobs, the celebrated college dropout, developed an obsession for reading as a young student. Books that he recommended everyone read include the following:

· 1984 by George Orwell

· Diet for a Small Planet by Frances Moore Lappé

· Moby Dick by Herman Melville

· The Innovator’s Dilemma by Clayton Christensen

· King Lear by William Shakespeare

· The Collected Poems of Dylan Thomas by Dylan Thomas

A recent study found that benefits of leisure reading each day included improvements in the following:

· Mental stimulation …

· Memory

· Focus and concentration

· Analytical skills

· Vocabulary

· Writing skills

Read and read some more

Books that are popular among your peers and required reading at many universities include the following:

· Drive: The Surprising Truth about What Motivates Us … by Daniel H. Pink (Riverhead Books)

· Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race by Margot Lee Shetterly (William Morrrow)

· Garbology: Our Dirty Love Affair with Trash by Edward Humes (Avery)

· The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot (Crown)

· Stuffed and Starved: The Hidden Battle for the World Food System by Raj Patel (Melville House)

· Educated: A Memoir by Tara Westover (Random House)

Self-educated leaders

Can reading be a sole source of education, without a formal degree? Becoming “educated” is an achievement people work for, not a status based on who they are and how they were born. Some self-motivated people earn their education and notoriety solely through reading rather than in a credentialed institution.

Your familiarity with the following autodidacts reflects your reading background.

Technology Leaders |

Political Leaders |

Business Leaders |

Literary Leaders |

Steve Jobs |

Abigail Adams |

Andrew Carnegie |

Edgar Allan Poe |

Bill Gates |

Grover Cleveland |

Ray Kroc |

J.D. Salinger |

Michael Dell |

Frederick Douglass |

John D. Rockefeller |

Maya Angelou |

Orville Wright |

Patrick Henry |

Walt Disney |

Walt Whitman |

Wilbur Wright |

James Monroe |

Henry Ford |

Bob Dylan |

Paul Allen |

George Washington |

Estée Lauder |

Samuel Clemens |

Steve Wozniak |

Eleanor Roosevelt |

Ted Turner |

Herman Melville |

For a limited number of highly motivated and disciplined people, reading offers a path to self-education without a college degree. The autodidacts listed here are examples of the result of obsessive book reading. “Although I dropped out of college and got lucky pursuing a career in software, getting a degree is a much surer path to success,” wrote Bill Gates in a recent blog post. “College graduates are more likely to find a rewarding job, earn higher income, and even, evidence shows, live healthier lives than if they didn’t have degrees.” Also, you have the opportunity to experience an event that Bill Gates never experienced, a college graduation and family party.

Additional books that are frequently required for college writing reference include the following:

· Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

· Big Data Baseball: Math, Miracles, and the End of a 20-Year Losing Streak by Travis Sawchik (Flatiron Books)

· The Geography of Genius: Lessons from the World's Most Creative Places by Eric Weiner (Simon & Schuster)

· Blink: The Power of Thinking without Thinking by Malcolm Gladwell (Back Bay Books)

· Give and Take: Why Helping Others Drives Our Success by Adam Grant (Penguin Books)

· The Female Brain by Dr. Louann Brizendine (Harmony)