APA style and citations for dummies - Joe Giampalmi 2021

Packaging appearance: formatting and organization

Acing a first impression: formatting title page and page layout

Perfecting presentation: beginnings, endings, and other writings

Formatting research titles and organizing content represent real-life standardization of APA requirements — and increase readability for professors’ grading. Lack of consistent organization is like reading each page written in a different language. APA’s consistency begins with the title page and continues with the format and organization of content pages. Check out the following sections for more nitty gritty about formatting and organization.

![]() Ask your professor the following questions about page formatting and layout:

Ask your professor the following questions about page formatting and layout:

· Do your page layout preferences include any exceptions to APA guidelines?

· Are APA’s five levels of headings required?

· Is a model of your preferences for bulleted lists available?

Page formatting: consistency is key

Using page formatting is like avoiding walking into objects in a dark room: you know the layout. Consistent page formatting helps you navigate the page from top to bottom without running into any layout obstacles.

![]() When formatting an APA page of text, keep in mind the following guidelines:

When formatting an APA page of text, keep in mind the following guidelines:

· Create a one-inch margin on all four sides (a Microsoft Word default).

· Use Times New Roman, a friendly font for many eyes, at 12-point font size.

· Double-space lines and headings.

· Align paragraphs flush left and indent new paragraphs with a tab (or five spaces).

· Strive for a project word length between 2,500 and 3,000 words.

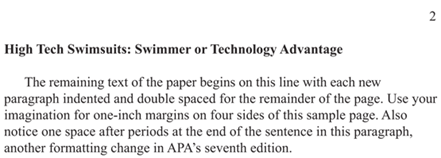

The main body of the paper begins on a new page after the title page (and following the abstract or executive summary if required). APA requires that the title be repeated on the first line of the first page following the title page. Figure 14-3 shows what page 2 looks like.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 14-3: Page 2 in an APA paper.

APA’s seventh-edition upgrades offer font options for students with accommodation needs. Optional fonts include Calibri 11, Arial 11, Lucida Sans Unicode 10, and Georgia 11. Times New Roman 12-point font is standard for most college papers.

![]() A serif is a small line or a flare of short strokes attached to the ends and corners of a letter. Look at this capital “A.” Note the small lines at the baseline on each side of the “A.” Each stem ends in a serif. Some serifs challenge readability for some people, especially when they’re reading from a distance. Fonts or typefaces without serifs, san (without) serif, accommodate a variety of readers, and so APA thoughtfully recommends the previously listed fonts.

A serif is a small line or a flare of short strokes attached to the ends and corners of a letter. Look at this capital “A.” Note the small lines at the baseline on each side of the “A.” Each stem ends in a serif. Some serifs challenge readability for some people, especially when they’re reading from a distance. Fonts or typefaces without serifs, san (without) serif, accommodate a variety of readers, and so APA thoughtfully recommends the previously listed fonts.

![]() “I can’t open your file.” Is anything more stressful to you than receiving this email response from your professor after submitting your assignment? You can avoid this unnecessary stress by conforming to the program. Microsoft Word may be the most popular word processing program used in college. Pages and Google Docs are also popular, but check with your professor. Almost all professors’ computers are compatible with Microsoft Word, and many professors respond to assignments with Word Markup, which isn’t compatible with Pages and Google Docs. Microsoft Word, standard to the PC, is easily adaptable to Apple and other platforms, and free versions are available online.

“I can’t open your file.” Is anything more stressful to you than receiving this email response from your professor after submitting your assignment? You can avoid this unnecessary stress by conforming to the program. Microsoft Word may be the most popular word processing program used in college. Pages and Google Docs are also popular, but check with your professor. Almost all professors’ computers are compatible with Microsoft Word, and many professors respond to assignments with Word Markup, which isn’t compatible with Pages and Google Docs. Microsoft Word, standard to the PC, is easily adaptable to Apple and other platforms, and free versions are available online.

Page organization: Sequence is essential

Page and content organization are the supply of information that flows to the reader and requires logic, sequence, and pace. The body of content is organized into a beginning, middle, and ending — a strategy adaptable to introducing an argument, developing it, and applying it to a thesis. See Chapters 5 and 7 for structural organization and developing an argument.

Some advanced college papers include headings such as statement of the problem, methods, results, and discussion. These headings adapt within the organization of the beginning, middle, and ending. For example, results and discussion are adaptable to the ending of a piece of writing.

APA recommends a sequence of content pages that looks like the following:

· Title page

· Abstract or executive summary

· Text body of paper

· References

· Endnotes

· Tables and figures

· Appendixes

APA identifies labels for some of these content pages as section labels, which are positioned at the top of a new page, bold, capitalized, and centered. Section labels include abstract, references, endnotes, tables, figures, and appendices. Because section labels require a new page, you need to insert a hard page break at the end of the page that finishes the previous section.

As a regular reminder, APA’s sequence of content and formatting is superseded by your professor’s requirements. Also, specialized papers for some courses and advanced certifications will require variations of APA requirements.

Using five levels of headings

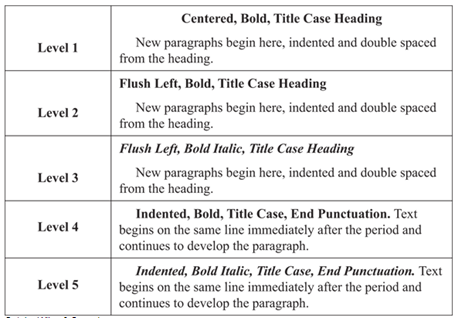

Another APA primary organizational strategy is the use of five levels of headings to differentiate levels of information. Figure 14-4 is a template of what the headings look like and how they coordinate with text.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 14-4: A template for headings.

![]() Similar to an outline, headings require two or more subheadings. A heading may have no subheadings, but not one subheading. Headings and subheadings for a topic, such as “National Healthcare Benefits a Nation,” look like the following:

Similar to an outline, headings require two or more subheadings. A heading may have no subheadings, but not one subheading. Headings and subheadings for a topic, such as “National Healthcare Benefits a Nation,” look like the following:

Level 1 |

Saves Long-Term Healthcare Costs |

Level 2 |

Children Benefit Earlier in Life |

Level 2 |

Adults Experience Fewer Chronic Illnesses |

Utilizing bulleted lists

APA offers bulleted lists as a content organizational strategy, a technique for writing sentences with large quantities of similar information. Bulleted lists are used throughout this book, including numerous lists in this chapter. Lists (bulleted, lettered, and numbered) increase readability by visually highlighting the beginning of each point. Here’s an example of a bulleted list on the topic of advantages of bulleted lists:

· Show similar multiple ideas in concise sentence format.

· Increase readability by highlighting ideas.

· Visually guide the reader to the beginning of each new idea.

· Increase readability by beginning each new idea with similar grammatical constructions.

· Utilize white space on the page to focus on major points.

CAPITALIZING BULLETED LISTS

Capitalization for bulleted items follows standard capitalization rules: If bulleted items are sentences, begin each item with a capital letter, as in the following examples:

· Set oven temperature at 450 degrees.

· Mix flour with sugar and salt.

· Combine wet ingredients with dry ingredients.

If bulleted items are phrases, not sentences, begin each item with a lowercase letter (unless the first word is a proper noun), as in the following list of strategies that contribute to academic success:

· managing time

· balancing course work and social life

· dedicating time for reading and writing.

Because these academic strategies aren’t individual sentences, they aren’t capitalized or punctuated at the end of each item. But the end of the last strategy (dedicating …) is the end of the sentence and requires end punctuation. End-punctuation omission at the end of a list of nonsentence items is a common neglect of college writers.

If you’ve been an observant reader throughout this book, you’ve noticed the For Dummies style includes capitalization of list items that aren’t sentences. Also note in the previous list that each academic-strategy item begins with the same grammatical construction, a gerund (managing, balancing, and dedicating). See Chapter 6 for more information on parallel structure.

PUNCTUATING BULLETED LISTS

APA offers the option of end-item punctuation for lists of phrases. Here’s what ending punctuation with commas looks like:

· managing time,

· balancing course work and social life,

· dedicating time for reading and writing.

A variation of comma end-item punctuation is semicolon end-item punctuation, when items contain a series of commas. Here’s what semicolons at the end of lines look like:

· managing time, work, and play;

· balancing course work, social life, and home life;

· dedicating time for reading and writing.

![]() This end-list punctuation style isn’t preferred among popular publishers and isn’t used in this book. A good punctuation guideline is similar to one for consuming calories: Fewer is healthier.

This end-list punctuation style isn’t preferred among popular publishers and isn’t used in this book. A good punctuation guideline is similar to one for consuming calories: Fewer is healthier.

Using numbered lists

Numbered lists, unlike bulleted lists, represent sequential steps in a process. Here’s an example of numbered steps to complete a research project:

1. Identify a research topic that interests you.

2. Research background information to help focus the topic.

3. Formulate a research question and argument.

4. Research sources to develop the argument.

5. Evaluate the argument.

6. Summarize and cite sources.

7. Create a reference list.

8. Draft a first copy.

9. Elicit feedback and revise drafts at three levels.

10. Edit and submit.

Listing terms and definitions

Another variation of lists is the term-and-definition format, which looks like this.

· easy listening: mood-generating music without vocals or a focus on pop and rock hits

· classical: an orchestral musical style that developed between 1750 and 1825 in reaction to the restrictions of baroque

· grunge: music developed from rock and punk, popular in the ’90s

APA doesn’t capitalize terms. The term definition ends with a period only when a sentence follows the definition. Here’s what that looks like:

· grunge: music developed from rock and punk, popular in the ’90s. You won’t find too many professors who listen to grunge music in their offices.