APA style and citations for dummies - Joe Giampalmi 2021

Focusing on essay structure and formatting

Understanding first year writing: APA essays and reaction papers

Perfecting presentation: beginnings, endings, and other writings

Congratulations on the A’s you earned for your high school essays; your professors are not impressed. They expect more, as does APA, which established standards for academic writing style and documentation.

Essays and research papers share similar foundations of a beginning, middle, and ending, but some essay elements vary. Here’s a look at the essay’s major parts and their purposes.

· Introduction: A title that predicts the essay’s contents, a first sentence that engages the reader, an opening that encourages reading, and a transition from the opening to the body.

· Body: Middle paragraphs that develop the thesis, supporting it with examples, data, and experts’ opinions integrated with the author’s opinion (source engagement).

· Ending: Reflection and a final reader message, such as “what if” and “so what,” and referencing the opening.

![]() Your professor expects much more than a summary. The last paragraph is the last piece of information your professor reads before beginning the grading process.

Your professor expects much more than a summary. The last paragraph is the last piece of information your professor reads before beginning the grading process.

Keeping your essay moving

Essays have fewer moving parts than research papers. They lack the research paper’s abstract, table of contents, figures and tables, and appendices. But successful essays do require a strong focus, condensed development, and intense engagement — in addition to memorable reader value. Here are some essay approach strategies for achieving those objectives:

· Analyze assignment requirements and identify wording of major tasks, such as argue, trace, prioritize, explain, and compare.

· Read background information on the topic.

· Research sources for thesis support and author engagement.

· Outline content for the beginning, middle, and ending.

· Identify citations and corresponding references.

![]() Your professor may require a reference list for some essays. Always ask. Review sources and reference lists in Chapters 11 and 12.

Your professor may require a reference list for some essays. Always ask. Review sources and reference lists in Chapters 11 and 12.

Writing a memorable essay title

Titles are as important to essays as names are to courses. Would you read a book that had an uninteresting title, order an entrée with an unappetizing name, or go to a movie with an unappealing title? Obviously, no, and neither would your professor have much enthusiasm in reading your essay with an uninteresting title — also your first step toward ensuring an uninteresting grade.

When you begin an essay assignment (or any other writing assignment), identify a working title, using it as a general reference to the topic that provides some focus until you identify your formal essay. Professional writers finalize titles at the end of their projects when they know the content they’re titling.

![]() Begin your essay with a title that identifies the topic and previews the argument’s focus. Essay titles are less formal and more playful than research titles. Here are some title techniques and examples:

Begin your essay with a title that identifies the topic and previews the argument’s focus. Essay titles are less formal and more playful than research titles. Here are some title techniques and examples:

· Repetition: Repeat sounds that attract reader attention. Perfect Apartment Pets; Tips for Transitioning into College Technology; Major College Admissions, Major Admission Problems

· Rhymes and opposites: Engage with language memorable to readers. Small Colleges with Big Debt

· Puns: Play with language that appeals to readers. Service Projects That Make Dollars and Sense

· Literary references: Refer to classic literature familiar to your readers. The Best of College Athletics, The Worst of College Athletics; The Walter Mitty of Madison Avenue; To Fee or Not to Fee

![]() Avoid titles that promise too much and reveal lack of focus: Three Dozen Steps for a Fantastic College Experience.

Avoid titles that promise too much and reveal lack of focus: Three Dozen Steps for a Fantastic College Experience.

Starting your essay with a bang

The most important sentence that may influence your grade is the first sentence of your essay. Your investment in the extra time can produce high yields. Follow the title with a first sentence that engages the reader. First-sentence and opening strategies for essays include the following:

· Expert quotations: Connect readers with words of experts. “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results,” allegedly said Albert Einstein.

· Unusual information: Surprise readers with little known information. The Nation’s Report Card, The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), reveals a startling fact about students who score high in all subject areas: They write more in school than students who score poorly.

· Series of questions: Challenge readers with questions on the topic, such as: When do we stop college tuitions that approach a hundred thousand dollars a year? When do we stop student loans that exceed monthly luxury car payments? When do we stop the insanity of the cost of higher education?

· Emotional appeal: Appeal to readers’ sentiments, such as: Next to loving and caring about their children, parents’ most important responsibility is to provide them with the best education available. Fulfilling your child’s educational needs requires your active participation. Making homework sessions a regular part of your nightly routine is an excellent way to do this. Your child’s educational tomorrow is based on the accumulation of help with each night’s homework assignments today.

· Summary: Preview the topic with one sentence, such as: Is all work and no play synonymous with college success? Not according to a ten-year study by a team of Harvard researchers who analyzed academic habits of a successful college experience.

· Anecdotes: Describe a personal experience that previews the topic, such as: When I started freelance writing in the late eighties, I frequently asked editors to recommend the best book for future writers. The book unanimously suggested, and the book that remains the foundation of my teaching and writing, is Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style.

![]() Don’t begin an essay (or any other college paper) with a standard dictionary definition.

Don’t begin an essay (or any other college paper) with a standard dictionary definition.

![]() Don’t underestimate the importance of an engaging title and opening. Research on scoring essays shows that strong essay openings encourage scorers to think, “This essay is going to be a strong piece of writing, and I’m going to find the evidence to support the good grade I think it deserves.”

Don’t underestimate the importance of an engaging title and opening. Research on scoring essays shows that strong essay openings encourage scorers to think, “This essay is going to be a strong piece of writing, and I’m going to find the evidence to support the good grade I think it deserves.”

Risky writing reinforces reader interest

Essay readers expect information. Unlike research readers, they also expect entertainment and an occasional surprise. Here are some examples of rhythmical language techniques that provide entertainment and surprise:

· Adjective noun patterns: Many college students experience the frustration of a wet pet.

· Verbs in successive clauses: The candidate backed by one party was attacked by the other party.

· Compound nouns: Ocean resorts offer sun and fun.

· Verb noun rhymes: Pennsylvania drivers fear deer every fall. Stop texts; stop wrecks.

· Compound action words: Successful people know when to stop worrying and start producing.

Giving the body what it needs: Figurative language

Figurative language that occasionally elicits a reader’s smile adds reader interest while developing the body of the essay. Here are some examples:

· Personification: Attributing human qualities to inanimate objects. Alaskan spruce trees look tired in the summer.

· Similes: Comparing the familiar with the unfamiliar. Walking on a cold bathroom floor is like ice-skating barefooted.

· Metonymy: Words that express a broader idea. English author Edward Bulwer-Lytton said, “The pen is mightier than the sword.”

· Chiasmus: A verb reversal commonly used in speech. Joe Logue, my high school coach, always said, “When the going gets tough, the tough get going.”

John F. Kennedy said, “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”

· Hyperbole: Extreme exaggeration. My printer drinks gallons of ink.

Avoiding crash endings

Everything that begins has an end — think about that. Here are some techniques for ending essays.

· Lead-reference: Clarifies or amplifies the opening and unites the beginning and ending

· Memorable sentence: Leaves the reader with an inspirational message

· Transition: Amplifies the message from the previous paragraph

· So what: Provides the big-picture implication

· Prediction: Expresses what could happen as a result of this message

Formatting your essay

Essay structure lacks the complexity of research structure because research support depends on data, whereas essay support depends on explanation. Consequently, APA provides fewer formatting guidelines for essays, and formatting becomes the primary responsibility of the professor. With your professor’s guidelines taking precedence, here are some standard formatting guidelines for essays:

· Length between 650 to 700 words

· Margins one inch on all four sides

· Double spaced text and headings

· Times New Roman font, 12-point size

· No running head

· Page numbers in the upper-right corner

· A title page with the title placed in the middle of the page. If a separate title page is required, use the research paper title page design in Chapter 14.

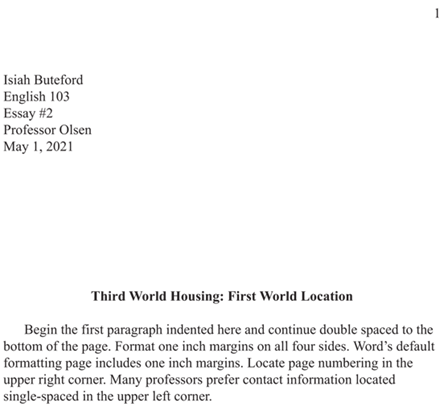

An acceptable design for a title page includes the following:

· In the upper-left corner, single space your name, the course name, the assignment name, the professor’s name, and the due date.

· Begin the title about one-third down the page. Type the title in title case (Chapter 14), center, and bold. Don’t underline or italicize.

· Begin text double spaced below the title. Indent new paragraphs.

If your professor doesn’t provide guidelines for an essay title page, refer to Figure 15-1.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 15-1: Example of essay title page.

Formatting your essay citations

Many college writing departments adopt an informal citation format exclusively for essays, which is an adaption of APA citation style. Ask your professor if your school provides a model for informal essay citations. Research papers require APA’s formal citation style.

Essays don’t require scholarly peer-reviewed sources of research papers, but one or two primary sources help support your paper. (You can review primary and secondary sources in Chapter 10.) Essays can thrive with a primary source and combinations of secondary and popular sources. Popular sources are written for general audiences and usually lack peer review and citations. They include publications such as Forbes, The Atlantic, U.S. News and World Report, National Geographic, and The Economist. Other popular sources include TED Talks and Office for National Statistics.

Successful college essays can be written with four to five sources, but check with your professor for requirements. Essays also require source engagement. Although research writing requires source engagement to support the research argument, essay source engagement requires integrating the author’s (your) essay argument with experts’ research. Here’s an example of essay engagement:

Brown’s (2015) “Managing Student-Athletes’ Stress” argues that “the combination of athletics, grades, and social life” positions student-athletes in the “at risk level” on Clarkson’s mental health scale (pp. 99—100). Robertson (2017) recommended “psychology maintenance” as part of athletes’ regular training routine (p. 79). As an athlete at a Division III school, I am not aware of the athletic pressure I envisioned at Division I scholarship schools, where athletic pressure and academic performance cause high stress on athletes.