APA style and citations for dummies - Joe Giampalmi 2021

Reading and responding: reaction paper basics

Understanding first year writing: APA essays and reaction papers

Perfecting presentation: beginnings, endings, and other writings

Reaction papers, also known as response papers, are the younger siblings of research papers and the cousins of essays. Reaction papers like to hang around with the college kids. Reading and responding by analyzing is similar to analyzing sources for your research papers.

![]() For your academic enjoyment, many professors require reaction papers as their go-to assignment. From the professor’s perspective, they’re easy to design and apply to almost every academic experience. They’re popular in content courses such as history, economics, psychology, and political science. They’re frequently assigned orally, which challenges you to be ready with your questions about assignment details. If you earn B’s on your research papers and essays, you should earn A’s on your reaction papers, because they lack the formulaic structure of research papers and essays. Like swimming in the ocean, you have many directions to go with reaction papers, but you should avoid rip currents and areas where you can lose control of your direction.

For your academic enjoyment, many professors require reaction papers as their go-to assignment. From the professor’s perspective, they’re easy to design and apply to almost every academic experience. They’re popular in content courses such as history, economics, psychology, and political science. They’re frequently assigned orally, which challenges you to be ready with your questions about assignment details. If you earn B’s on your research papers and essays, you should earn A’s on your reaction papers, because they lack the formulaic structure of research papers and essays. Like swimming in the ocean, you have many directions to go with reaction papers, but you should avoid rip currents and areas where you can lose control of your direction.

Reaction papers are also a test of your reading skills, especially between-the-lines critical-thinking skills such as evaluating, prioritizing, applying, contrasting, questioning, authenticating, and synthesizing.

APA’s stamp on reaction papers includes writing in an academic style, citing sources, and listing sources on a reference page. APA lacks specifics for title page design and formatting, but you can easily apply principles from research formatting. In these sections, I guide you along the way. If citations and references are not part of your requirement, using them accurately will impress your professor and improve your grade.

Here are some questions to ask your professor about essays and response papers:

· Do you have a preferred title page design?

· Is APA’s page formatting style acceptable?

· How many and what type of sources are required?

· Is a reference list required?

· Are formal citations required?

Writing a successful reaction paper

A successful reaction paper requires application of your two most important college skills, reading and writing.

Reading and reacting generally requires you to read one or a few articles and to respond with your supported reactions. If you are assigned two or more authors, you are expected to respond to a synthesis of concerns. You may also be asked to respond to a lecture, book, video, PowerPoint presentation, current event, website, or social media post. Your writing purpose is to engage with the author. You do not need to follow the chronological order of the readings.

![]() Some professors lie awake at night thinking of academic experiences to respond to — a class, a person in the news, a holiday, a podcast episode, a commercial, an election, a speaker, and so forth. Professors lose sleep thinking of experiences for students to react to.

Some professors lie awake at night thinking of academic experiences to respond to — a class, a person in the news, a holiday, a podcast episode, a commercial, an election, a speaker, and so forth. Professors lose sleep thinking of experiences for students to react to.

You can respond to reading by agreeing, disagreeing, questioning, or confirming. Your response can be generated by anger, surprise, belief, or doubt. Write your response guided by the principles of good academic writing, especially audience and purpose. You can review these principles in Chapter 5.

Other writing guidelines specific to reaction papers include

· Write in the first person I. Avoid the first-person plural we, and avoid third-person references such as the writer, the author, and the researcher. See Chapter 6 for more information on person (point of view).

· Regularly use the phrases “such as” and “for example” to support your reactions.

· Connect reactions to the course for which the paper was assigned, other courses, your life, society, books, the arts, current events, and your independent reading.

· Prioritize reactions you want to respond to.

· Support your reactions with partial quotations.

![]() Of course, you don’t want to write an unsuccessful reaction paper. But if you receive an unsuccessful grade, it could be attributed to any of the following:

Of course, you don’t want to write an unsuccessful reaction paper. But if you receive an unsuccessful grade, it could be attributed to any of the following:

· Summarizing rather than analyzing

· Submitting a paper that’s too short

· Lacking support for reactions

· Lacking citations and reference list, if required

· Formatting a reference list without hanging indentations

![]() If you want to overachieve, cite an outside source or two to additionally support a reaction. Include your citation in the reference list.

If you want to overachieve, cite an outside source or two to additionally support a reaction. Include your citation in the reference list.

Analyze; don’t summarize. Analysis includes who and what the experience affects. Here’s an example of analyzing and connecting a reading to a college experience:

Shatner’s (2020) principle of “creating a safe and supportive academic climate” is demonstrated in our class (pp. 84—85). Professor Callahan encourages us to express our opinion on course topics, especially when the opinion is unpopular. For example, I recently expressed an opinion that our college lacks equal support of men’s and women’s athletic teams. I said this as a female athlete in a class with numerous male athletes. Because of the respectful classroom environment created by Professor Callahan and his encouragement to create unpopular discourse, I felt confident to express my opinion. I felt comfortable knowing Shatner’s principles were part of my classroom experience.

Your writing response is preceded by your reading. Review Chapter 9 for strategies such as applying, questioning, evaluating, speculating, articulating, and synthesizing. Also read as a believer and doubter.

Organizing a reaction paper

Reaction paper organization includes the following structure.

Introduction

Identify the elements of the source(s) you’re reacting to (author, source, publisher, and publication date), followed by a topic summary of the source’s major points.

![]() You can exceed your professor’s expectations by creatively titling your reaction paper and beginning with an engaging first sentence prior to identifying your source. Here’s an example:

You can exceed your professor’s expectations by creatively titling your reaction paper and beginning with an engaging first sentence prior to identifying your source. Here’s an example:

Thesis

The thesis identifies the purpose of the paper and a promise to the reader of what will develop. Formulate a position that summarizes the responses you are reacting to.

Here are a few examples:

· First World countries have a moral obligation to share medical knowledge with Third World countries.

· People want their freedom; they also want their safety. Where do these two desires intersect?

· Support for public education is not a shared responsibility throughout the country; it should be.

Body

The body develops the thesis with references to evidence, conclusion, ideas, and description. Develop reaction points in separate paragraphs, supported with summary, paraphrase, quotations, and citations. Your grade depends on how well you support your reactions.

Ending

The ending represents your final thoughts on your reaction, the last message to the reader. Ending strategies include reflecting on the topic with a prediction, so what, or big-picture meaning.

Reference list

Insert a hard page break at the end of the last line of text. Center “References” in bold (not in quotations). See Chapter 12 for reference list guidelines. Be sure to include the source(s) you’re reacting to in the reference list.

From APA writing skills that I discuss in Chapter 5, prioritize the following skills when writing reaction papers: audience, purpose, tone, focus, and transitions.

Formatting a reaction paper

Here’s a look at APA formatting guidelines (some are similar to the research paper) that apply to reaction papers — assuming your professor didn’t provide any:

· Length about 3—4 pages, with about 800 words (a little longer than an essay)

· Margins one inch on all four sides

· Double-spaced text and headings

· Times New Roman font, 12-point size

· No running heads

· Page numbers in the upper-right corner, similar to research papers

· Heading levels, if applicable, similar to heading level guidelines in Chapter 14

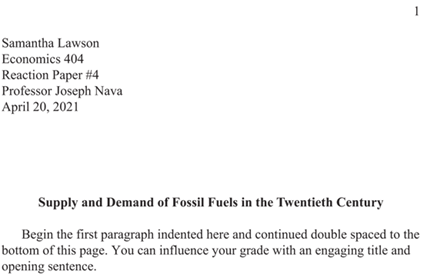

An acceptable design for a title page (see Figure 15-2) includes the following:

· In the upper-left corner, single space your name, the course name, the assignment name, the professor’s name, and the due date.

· Begin the title about one-third of the way down the page. Write the title in title case (Chapter 14), center and bold. Don’t underline or italicize.

· Begin text double spaced below the title. Indent new paragraphs.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 15-2: An example of an acceptable title page for reaction papers.

![]() Your professor’s first indicator of an unsuccessful paper is one that neglects to meet the length requirement. You may be a proficient, economical writer, but an assignment that is a page under length will raise suspicion and scrutiny. Many professors believe that papers that don’t meet length requirements are inferior papers.

Your professor’s first indicator of an unsuccessful paper is one that neglects to meet the length requirement. You may be a proficient, economical writer, but an assignment that is a page under length will raise suspicion and scrutiny. Many professors believe that papers that don’t meet length requirements are inferior papers.