How to write a lot: a practical guide to productive academic writing - Silvia Paul J. 2019

Specious Barriers to Writing a Lot

Writing is a grim business, much like repairing a sewer or running a mortuary. Although I’ve never dressed a corpse, I’m sure that it’s easier to embalm the dead than to write an article about it. Writing is hard, which is why so many of us do so little of it. When they talk about writing, professors and graduate students usually sound thwarted. They want to tackle their article or get to their book, but some big and stubborn barrier is holding them back.

I call these specious barriers: They look like legitimate reasons for not writing at first glance but crumble under critical scrutiny. In this chapter, we’ll look askance at the most common barriers to writing a lot and describe simple ways to climb over them.

SPECIOUS BARRIER 1

“I can’t find time to write,” aka “I would write more if I could just find big blocks of time.”

This barrier is the big one, the Ur-barrier from which most writing struggles descend. But as popular as it is, the belief that we can’t find time to write is still specious—much like the belief that people use only 10% of their brains. Like most false beliefs, this barrier persists because it’s comforting. It’s reassuring to believe that circumstances are against us and that we would write more if only our weekly schedule had more big chunks of open time. Our friends around the department understand this barrier because they struggle with writing too. And so we thrash through the copse and thicket of the work week, hoping to stumble out eventually into the open prairie.

Why is this barrier specious? The key is the word find. When people endorse this specious barrier, I imagine them roaming through their schedules like naturalists in search of “Time to Write,” that most elusive and secretive of creatures. Do we need to “find time to teach?” Nope—we have a teaching schedule, and we don’t fail to show up for our classes. If you think that writing time is lurking somewhere, hidden deep within your weekly schedule, you won’t write a lot. If you think that you won’t be able to write until a big block of time arrives, such as spring break or the summer months, then writing your book will take forever.

Instead of finding time to write, allot time to write. People who write a lot make a writing schedule and stick to it. Let’s take a few moments to think about a writing schedule that would work for you. Ponder your typical work week: are there some hours that are generally free every week? If you teach on Tuesdays and Thursdays, maybe Monday and Wednesday mornings are good times to write. If you’re free and mentally alert in the afternoons, maybe times later in the day would work well for you. If you have a friend who would like to sit and write with you in a quiet room every Friday from 9:00 a.m. to noon, perhaps the two of you could prove that misery does love company.

Chapter 3 digs into the care and feeding of writing schedules, so we’ll have much more to say about picking and fine-tuning a schedule then. For now, think of writing as a class that you teach. Most classes are around 3 to 6 hours each week, so schedule 4 hours for your “writing class” during the normal work week. Four hours doesn’t sound like much, but it’s plenty—approximately 240 minutes more than most people write in a typical week, in fact. Each person will have a different set of good times for writing, given his or her other commitments. The key is the habit—the week-in, week-out regularity—not the number of days, the number of hours, or the time of day. It doesn’t matter if you pick one day a week or all five weekdays—just choose regular times, chisel them into the granite of your weekly calendar, and write during those times.

I’ve followed many schedules over the years. My first writing schedule, based on the fragments I can assemble from my parenthood-induced amnesia, was from 8:00 a.m. to 10:00 a.m., Monday through Friday. I would set my alarm for 8:00 a.m., grouse about the inhumanly early hour, and then write for 2 hours at home. Looking back, I have to snicker at my past self. I felt so hard-core when I woke up at 8:00 a.m., like I should drink raw eggs, rack up a barbell, and get a neck tattoo after wrapping up the day’s writing. Having kids put an end to that idyllic writing schedule, so I shifted to writing from 5:00 a.m. to 7:00 a.m. at home every weekday—sticking to that schedule for a few years merits a barbed wire neck tattoo. For the past few years, I write on campus after dropping the kids off at school, roughly from 7:50 a.m. to 9:30 a.m.

Instead of scheduled writing, most academics use a stressful and inefficient strategy called binge writing (Kellogg, 1994). The drama of binge writing has three acts. First, people spend at least a month or two intending to write, ruminating about their half-done project, and stewing in guilt and worry. Eventually, anxiety over the looming project goads them into claiming a huge chunk of time—perhaps a whole Saturday or the week of spring break—during which they fling themselves at their neglected project with the cold and steely determination of someone suiting up to investigate an odd smell coming from the crawl space. Finally, after an eyebrow-singeing blaze of typing, they emerge hours later, weary and bedraggled, covered in coffee grounds and printer toner, relieved to have more words on the page, but discouraged at how hard-fought those words were.

And then the binge-writing cycle begins anew—more waiting, more worry, more eyebrow-singeing. Binge writers spend more time feeling guilty about not writing than schedule-followers spend writing. Writing schedules, aside from fostering much more writing, dampen the drama that surrounds academic writing. When you follow a schedule, you stop worrying about not writing, stop complaining about not finding time to write, and stop indulging in ludicrous fantasies about how much you’ll write over the summer. Instead, you write during your allotted times and then forget about it. We have better things to worry about than writing, such as whether we’re drinking too much coffee or why the cats have started hoarding knitting needles and steel wool. But we needn’t worry about finding time to write: I’ll just get back to this book tomorrow at around 7:50 a.m.

People are often surprised by the notion of scheduling. “Is that really the trick?” they ask. “Isn’t there another way to write a lot?” There are some options you could consider—irrational hope, cussed stubbornness, or intensive hypnotherapy that transforms you into the kind of person who finds writing fun and easy—but, for most of us, making a writing schedule and sticking to it is our best option. After researching the work habits of successful writers, Ralph Keyes (2003) noted that “the simple fact of sitting down to write day after day is what makes writers productive” (p. 49). If you allot 4 hours a week for writing, you will be astounded at how much you will write in a single semester. In time, you’ll find yourself committing unthinkable academic heresies. You’ll submit grant proposals early; you’ll revise and resubmit manuscripts quickly; and, one day, you’ll say something indelicate when your pal in the department says, “This semester is killing me—I can’t wait for the summer so I can finally do some writing.”

SPECIOUS BARRIER 2

“I need to do some more analyses first,” aka, “I need to read a few more articles/books/letters/epigraphs/scrolls.”

Like all specious barriers, the idea that “I need to do more prep work first” sounds reasonable. “After all,” you might say, “you can’t write something without a lot of reading.” But there’s a line between productivity and procrastination—a deep trench, really, that more than a few assistant professors have fallen into while walking to the library to pick up the last book they need to read before starting to write their own.

Academic culture reinforces this barrier. We respect perfectionism and diligence. We know that scholarship requires freakish amounts of reading, laborious data analysis, and regrettably necessary trips to inconvenient archives in Barcelona and Paris. But binge writers are also binge readers and binge statisticians. The bad habits that keep them from getting down to writing also keep them from doing the prewriting (Kellogg, 1994)—the reading, outlining, organizing, brainstorming, planning, and number-crunching necessary for typing words.

It’s easy to pull away this creaky crutch—do whatever you need to do during your allotted writing time. Just as it’s easy to put off typing, it’s easy to put off the prep work, so stuff it all into the scheduled time. Need to crunch some more stats? Need to read some articles, review page proofs, or read books about writing and publishing? Your writing schedule has the space for all that.

Writing is more than typing words. For me, writing’s endpoint is sending an article to a journal, a book to a publisher, or a grant proposal to a funding agency. Any activity that gets me closer to that goal counts as writing. When writing journal articles, for example, I often spend a few consecutive writing periods working on the analyses. Sometimes I spend a whole writing period on ignominious aspects of writing, like reviewing a journal’s submission guidelines, making figures and tables, or checking page proofs.

Academic writing has many parts. We will never “find the time” to retrieve and read all of the necessary articles, just as we’ll never “find the time” to write a review of those articles. This is another reason why scheduling time to write is the way to write a lot.

SPECIOUS BARRIER 3

“To write a lot, I need a new computer” (see also “fancy productivity software,” “a nice office chair,” “a better desk,” “a home office”).

Of all the specious barriers, this is the most desperate. I’m not sure that people really believe this one—unlike the other barriers, this may be a mere excuse. When I started writing seriously during graduate school, I bought an ancient computer from a fellow student’s boyfriend. This computer was prehistoric even by 1996 standards—no mouse, no Windows, just a keyboard, a soothing blue DOS screen, and WordPerfect 5.0. When the computer died, taking some of my files with it to its grave, I bought a laptop that I typed into the ground. Even now, I’m writing this book on a “state-contract special” that is so old that it occasionally scowls and shakes its fist at me from its porch rocker. My laser printer is now old enough to run for a city council seat.

If you find yourself blaming your lack of “productivity tools”—an Orwellian euphemism for “high-tech procrastination devices”—remember the inkwell and typewriter. What would your 1920s scholarly self, with its rakish pocket watch or fetching bob, say if it overheard you pining for some fancy new software or device? And what would you say if you heard your 1920s self and its excuses?

§ “Blast it all, someone else has the card catalog drawer I need—I can’t possibly work on my book today.”

§ “Curses, reading that source would require walking across campus, entering the library, and retrieving physical printed matter. The indignity!”

§ “I’m waiting for the next generation of typewriters to come out before starting my next book. I hear they’ll have a number 1 key so I won’t have to press the lowercase l key when typing dates. Think of how much faster I’ll write!”

Scholars wrote lots of books—big, fascinating, profound, important books—before digital “productivity tools” were invented. Indeed, one wonders if writing was easier for them. They could simply write, happily hunting-and-pecking away without the itchy suspicion that someone, somewhere, just said something on the Internet.

What about chairs and desks and rooms? For nearly a decade I used a metal folding chair as my official writing chair. When the folding chair retired, I replaced it with a more stylish, but equally hard, vintage fiberglass chair. For the curious, Figure 2.1 shows where I wrote this book’s first edition. That room had a big, simple desk with my laser printer (in its jejune days) and a coaster for my coffee. Before I splurged on that desk, I had a $10 particleboard folding table, which in a nod to fashion I covered with a $4 tablecloth. I wrote most of a book (Silvia, 2006) and a couple dozen articles sitting on my folding chair in front of that folding table.

FIGURE 2.1. My writing room from long ago.

The more I write, the worse my writing environs become. I’ve been working at my university long enough to know where the unloved and deserted rooms are, so I usually do my morning writing in a lab room that resembles a place that scientists hastily abandoned in the opening scene of a disaster movie. Figure 2.2 shows where I wrote most of a recent book (Silvia, 2015) and much of the second edition of this one. Note the hard plastic chair and particleboard table with a stylish fake wood-grain top—I’ve gone full-circle, I suppose.

FIGURE 2.2. A recent writing hovel.

Unproductive writers often bemoan the lack of “their own space” to write. Perhaps parenthood has shifted my standards, but any space where stuffed animals are unlikely to hit the back of my head will suffice. In a string of small apartments and houses, I wrote on a small table in the living room, in my bedroom, in the guest bedroom, in the master bedroom, and even (briefly) in a bathroom. I wrote the first edition of this book in the guest bedroom in my old house. But that room was eventually lost to cribs and changing tables, so I set up a lounge chair, lamp, printer, and coffee coaster at the end of a hallway. Even now, I don’t have my own space at home to write. But I don’t need it—there’s always a free bathroom.

“In order to write,” wrote Saroyan (1952), all a person needs “is paper and a pencil” (p. 42). In fact, Saroyan might have overstated it. As Fowler (2006) reminded us, “You can write only with your brain” (p. 1). We can’t pin the blame on old computers and slow WiFi—only making a schedule and sticking to it will make us productive writers.

SPECIOUS BARRIER 4

“I’m waiting until I feel like it,” aka, “I write best when I’m inspired to write.”

You usually hear this barrier among writers who really, really don’t want to make a writing schedule. “My best work comes when I’m inspired,” they say. “It’s no use trying to write when I’m not in the mood. I need to feel like writing.” This barrier is cruel because it is half-true. We all have moments when we feel inspired—we lose sense of time, the sentences tumble out, and what we write, as F. Scott Fitzgerald (1955) eloquently put it, is “good, good, good” (p. 7).

Inspiration is like a slot machine. The problem isn’t that inspiration never strikes, it’s that inspiration strikes erratically and unpredictably. Flow’s fickle quality is what hooks us. That’s why so many people wait for inspired moments to hit, puzzled about why the muse is forsaking them and their footnotes.

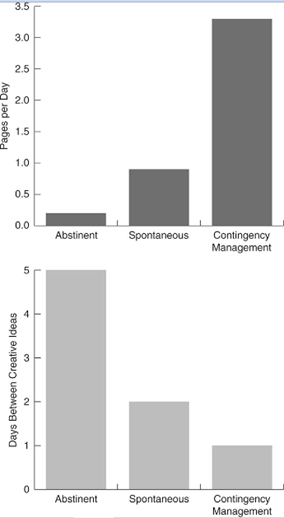

Inspired moments are precious, but we needn’t wait for inspiration to do good work. Robert Boice (1990) gathered a small sample of college professors who struggled with writing, and he randomly assigned them to use different writing strategies (p. 79). People in an abstinence condition were forbidden from all non-emergency writing; people in a spontaneous condition scheduled 50 writing sessions but wrote only when they felt inspired; and people in a contingency management condition scheduled 50 writing sessions and were forced to write during each session. (They had to send a check to a disliked organization if they didn’t do their writing. The resulting incoming junk mail would have hurt more than the money.) The outcome variables were the number of pages written per day and the number of creative ideas per day.

Figure 2.3 shows what Boice found. First, people in the contingency management condition wrote a lot—they wrote 3.5 times as many pages as people in the spontaneous condition and 16 times as much as those in the abstinence condition. People who wrote “when they felt like it” were barely more productive than people told not to write at all—inspiration is overrated. Second, forcing people to write boosted their creative ideas for writing. The typical number of days between creative ideas was merely 1 day for people who were forced to write; it was 2 days for people in the spontaneous condition and 5 days for people in the abstinence condition. Writing breeds more good ideas for writing.

FIGURE 2.3. The effects of different writing strategies on (top) the number of pages written per day and (bottom) the modal number of days between creative writing ideas. Data from Boice (1990).

Another reason not to wait for inspiration is that some kinds of writing are so unpleasant that no one will ever feel like doing them. Who wakes up in the morning with an urge to write about “Specific Aims” and “Consortium/Contractual Arrangements?” Who enjoys writing awkward and self-conscious “yay, me!” personal statements for fellowships? If you have moods where you’re gripped by a desire to read the Department of Health and Human Services Grants.gov Application Guide SF424 (R&R), you have a bright future. But the rest of us need much more than “feeling like it” to finish a grant or fellowship proposal.

Struggling writers who “wait for inspiration” should get off their high horse and join the unwashed masses of real academic writers. The ancient Greeks assigned muses for poetry, music, and tragedy, but they didn’t mention a muse for references and footnotes. Our writing is important, but we don’t have fans lurking outside the conference hotel hoping for our autographs on recent issues of the Journal of Vision Science. We want our writing to be as good as it can be, but we’ll settle for “be” if we can’t get “good.”

Ralph Keyes (2003) has shown that great novelists and poets—people who we think should wait for inspiration—reject the notion of writing when inspired. The prolific Anthony Trollope (1883/1999) wrote that

there are those . . . who think that the man who works with his imagination should allow himself to wait till—inspiration moves him. When I have heard such doctrine preached, I have hardly been able to repress my scorn. To me it would not be more absurd if the shoe-maker were to wait for inspiration, or the tallow-chandler for the divine moment of melting. . . . I was once told that the surest aid to the writing of a book was a piece of cobbler’s wax on my chair. I certainly believe in the cobbler’s wax much more than the inspiration. (p. 121)

How do these great writers write instead? Successful professional writers, regardless of whether they’re writing novels, nonfiction, poetry, or drama are prolific because they write regularly—usually daily. As Keyes (2003) put it, “Serious writers write, inspired or not. Over time they discover that routine is a better friend to them than inspiration” (p. 49). One might say that they make a schedule and stick to it.

SPECIOUS BARRIER 5

“I should clear the decks before getting down to writing,” aka, “I’ll write even faster later on if I wrap up all this other stuff first.”

This barrier involves ingenious self-deception. We convince ourselves that by avoiding writing, we are actually writing faster. “Sure, I could write a couple pages this week,” we say to ourselves, “but if I spend this week clearing the decks of grading and service, then I’ll have a clear mind and can write much faster next week.” Indeed, a tell-tale sign that spring break is a week away is the sudden flowering of calculus among the humanities professors. “Why write two pages this week and four next week, for an average of three pages per week, when I could write zero this week and 10 next week, for an average of five per week?” they’ll say. “It’s all about the rates and slopes, people!” If anything could make a Renaissance historian dig into partial derivatives and Laplace approximations, avoiding working on a book is it.

“Clearing the decks” is mental alchemy: We transmute the lead of procrastination into the gold of efficiency. But let’s be candid with ourselves. By avoiding writing for a week and throwing ourselves into other tasks, we aren’t planning, preparing, or positioning ourselves for a great bout of writing later—we’re just procrastinating. And those decks are never going to be clear. We can sweep the jetsam of e-mail and memos and reviews from our humble rowboat, but when our bosses clear the decks of their enormous container ships and luxury yachts, where do you think their rubbish lands? A professor’s decks are never clear: there will always be barnacles to scrape, cannons to polish, and scurvy-stricken grad students to free from the brig.

When you use a weekly writing schedule, you stop seeing some weeks as lost causes. The first week of class? Follow your writing schedule. The last week of class? Writing schedule. The week before spring break? Writing schedule. And spring break itself? Maybe you should take spring break off—you’ve earned it.

CONCLUSION

Humans are immensely creative animals. No other species can come up with such fiendishly compelling excuses for not writing, and only people can make procrastination look productive. Bonobos and orangutans, for example, just sit around and groom each other when they don’t want to work on their dissertations, but humans will throw themselves into reading and grading and learning new citation software.

This chapter has debunked some common reasons people give for not writing this week, from searching for time to clearing the decks. We’ve all indulged in these mental comfort blankets, but it’s hard to type when you’re wrapped in a blanket. Instead, I developed this book’s core idea—academics should schedule time for writing much like we schedule time for teaching and tackle writing’s many tasks during that time.

Writing schedules are simple in theory but not always easy in practice. What are good times and places to pick? What project should we tackle first? How can we defend our frail schedules against the work week’s many time predators? The next chapter describes some simple tools for turning your fledgling schedule into a fearsome writing habit.