Writing Smart, 3rd edition - Princeton Review 2018

Research papers

Writing research papers

For many people, the research paper is the most daunting academic task. But rest assured, research papers are highly doable and can even be relatively painless when you have a clear plan of attack. If you follow the steps discussed in this chapter, writing a research paper is no more difficult than following an intricate recipe for chocolate cake.

Research paper format

A research paper is really just a long essay, so it will have the same basic construction.

Introduction

Some papers will ask you to prove some sort of argument and others will ask only for loads of information about a subject. If you are trying to prove a thesis, indicate that during the introduction. If you are writing a purely informative paper, set forth the subject of the paper in the introduction along with the aspects of the subject you intend to discuss.

Body

The body of the paper consists of the information you have garnered through your extensive research. In a paper that presents an argument, the body includes a cogent support of the argument. It also includes one section for the opposition’s case, which you then endeavor to disprove. You make your own argument much more convincing by allowing the reader to see the counter-arguments made, and then a reasoned rebuttal of such.

In an informational paper, the body presents all the research on your subject, in a logical and organized manner.

Separate your research into themes, and then build the paper theme by theme, using paragraphs to separate them. In a paper that’s more than 25 pages, paragraphing may not be sufficient to separate your themes. In that case, subsections may be necessary, and within those subsections you may need to create paragraphs. Whatever format you select, make sure you maintain it consistently throughout your paper.

Research papers also allow for other media such as photographs and illustrations, so the body of the paper often includes both text and visual material. Take full advantage of this and use them where appropriate to accent and allow the reader to attach visual images to the text. A research paper is like a long magazine article, and what usually interests you in long magazine articles? Not just the information presented, but also the manner in which it is displayed and—let’s be honest here—the fancy pictures. A research paper should be interesting, and a pleasing layout can be an important part of that.

The body of the paper refers to sources quite regularly, as that is the aim of a research paper. Any direct quotes from sources or paraphrases from research sources are footnoted. This means, after a quote or paraphrase, put a number (these references will go in order of the paper), and at the bottom of the page, you write the source of the note, including title, author, publisher. You will find more information on how to write footnotes in the Specifics section of this chapter.

Conclusion

The conclusion restates the main point and indicates how the paper has accomplished it. If your paper argued for a particular thesis, reiterate how that thesis was proved by the successive examples. If your paper described a phenomenon, summarize the information presented and what it showed you.

Bibliography

One thing that distinguishes a research paper from other nonfiction writing is the inclusion of a bibliography. Here you will indicate the sources you used for the information you presented in the paper. Anything you read that aided you in your understanding of the subject is included here, according to the guidelines described later in this chapter.

Writing the paper

Step 1: Select your topic or thesis

Some teachers may assign a specific topic, but most will provide a possible range and allow you to select your own. A research paper is an opportunity for your teacher or professor to assess your research and writing skills. Typically, your instructor will assign a paper of some specified length—5, 10, or 20 pages—on a variety of topics. “Cover some important issue about Colonial history in the early 1800s,” she might say. It is then up to you to select the exact topic, find out all there is to know about it, and write the thing. For instance, our friend Tim might be assigned a paper.

Tim is taking a class in nutritional sociology and his teacher announces, “A five-page research paper on some way sugar’s influence is seen in our society, due in one month. I expect you to research and annotate this responsibly.”

The most important criteria for a topic are its interest to you and the breadth of the topic.

Interest to you

If the topic you select holds no appeal, it is very doubtful your paper will be interesting to you or your reader. This can lead to problems, because if you are not interested, it will be that much more difficult to get yourself to write the darn thing, and what you do write will not be your best. Even if the range of topics does not light your fire, try to find an angle that does. You may not be interested in the Reconstruction-era South, but you may be interested in the race relations, health care, or leisure activities of that time. A bit of research here into the range of topics from which you have to choose can be extremely beneficial. Read for things that catch your interest. Look at titles of books for ideas on what other writers have been interested in; you may be inspired.

Tim reads up on sugar at the library. He talks to people in the street about sugar. He eats a packet of sugar straight out of the sugar bowl in a restaurant, provoking complaints to the management from other customers. He listens to “A spoonful of sugar makes the medicine go down” and briefly considers writing his paper about sugar in the modern American musical; his research is blocked by his inability to find any other references to sugar in musicals, with the notable exception of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which he finds frighteningly hallucinatory. He is seen walking through the street clutching a bag of sugar and shaking his head, bewildered.

Breadth of topic

This is generally the stickiest issue when writing a paper. You want your topic to be small enough to cover in a paper, but broad enough that you can wring 10 or 20 pages out of it. Though you would be astounded on what people can base a 200-page book, a paper on the Reconstruction-era south would probably need closer to 1,000 pages, while the sash of Robert E. Lee’s uniform would probably fill only one good paragraph.

Tim briefly considers a paper about sugar in general, then goes to the library and finds 250 books on that topic. Too many. He regroups and considers a paper about the first bite of a candy bar; is it different from the other bites? He returns to the library, finds nothing.

Step 2: Get your topic approved

Before you begin searching for the perfect quote, make sure the topic you have chosen is an acceptable one. Few things are worse than starting a huge bulk of research or writing only to find out that it was all for nothing. If your topic is off the mark, your teacher or professor can guide you to one more suitable. You can’t lose by asking.

Frustrated, Tim visits his teacher after class. “The first bite of a candy bar?” she asks.

“Yes,” says Tim. “It’s the part of a candy bar I like the best.”

“Well,” the teacher says, “if it’s candy bars you’re interested in, why don’t you write your paper on that? I myself am a Milky Way fan. I love nougat.”

Tim ponders this. Could it be, he wonders, that specific personality types like specific types of candy bars? He proposes this thesis to his teacher. Intrigued, she approves his paper topic.

Step 3: Conduct the research

Your main task is to find out as much as you can about your topic. You may be writing a research paper in which you are arguing for one thesis or another, or you may be describing a particular situation or phenomenon. Find as much material as possible about your topic. Your librarian can help you, if needed. Librarians are great resources and are usually very willing to offer assistance.

It is not necessary for you to read every word of every book or article you find. Once you have amassed a collection, look through the tables of contents of the books and read those chapters that seem applicable. Look in the bibliography of these books for suggestions of other books that might be helpful.

As you collect your reference material, you should start taking notes. It is imperative that your notes be taken in an organized manner, because often this stage of the paper allows you to get your thinking done, and the more organized and clear your thinking, the better your paper. For each book or article you read, you should have a separate set of cards. At the top of each card put the title of the book from which the notes were gathered.

Then, at the top right corner of the card, mark how this note applies to your paper. This can be even easier if you use color coding. For instance, if your paper describes the secret lives of presidents, you might put the title of the book on the left, The Best and the Brightest, and on the right a red mark, indicating that this book is about Kennedy. Keep a master list explaining all your color codes and other reference marks in case you confuse yourself. Writing down quotes from books that strike you as important or particularly relevant is also helpful. Noting the page number here will come in handy when you want to footnote. Set aside a list of illustrations and photographs related to your subject.

Tim spends the next two weeks at the library, poring over psychiatric journals and candy wrappers. He sets up a complex cross-coding system involving colors and shapes. Cards related to daring types he marks with a triangle, stay-at-homes he marks with a square, tormented souls get a circle. Caramel candy bars are yellow, mint is green, mixtures are purple.

Tim has been working feverishly at the library. So thrilled is he by Professor Whipt’s article that he found three more articles by Whipt written in the past year. Tim collects fifty cards; his confidence grows. He knows he has something here.

Step 4: Make an outline

Once you have most of your research completed, you are ready to begin your outline.

An outline is absolutely indispensable for a research paper because it gives you an idea of what you are writing and what you need to write next. It also breaks your paper up into distinct parts, which will guide your writing process as well as allow you to write sections out of order. Bored with writing one section? Check your outline and start working on a different section that seems more interesting.

An outline is a sort of annotated table of contents for your research paper, and writing this outline provides you with an opportunity to organize your thoughts and your paper. The outline then provides you with a structure.

Write Your statement of purpose

You already have an idea of the subject of your paper, now you need to describe this subject with some sort of concise statement. For example: The purpose of this paper is to compare the courting rituals of men and women in 21st-century urban areas.

Organize your cards

Separate your cards into the order in which you want to refer to their topics. Depending on the length of your paper, you may have 3 to 30 subcategories. Try to organize them so that related subjects are close together, and there is some sort of natural transition between paragraphs.

Write your conclusion

We know, you’ve already written your statement of purpose in the first part of the outline, but it can only help to make it clearer to yourself, and the conclusion should refer to the organizational structure you’ve set up to support it.

While at home with his note cards, Tim contemplates his research. Just what is his thesis? What does his research lead him to? He knows there is a psychology to which chocolate bars different people choose, but what is it? He writes:

Thesis: Candy bars and personality—is there a connection? Yes.

Tim consults his note cards and orders them into a logical thought process.

I. Psychology has long posited that there is a strong connection between the types of foods we eat and our psyches.

A. Hogg’s study of food and society

1. Quote about judging society by food on card 2

2. How long study went on

B. Weird nutritional shakes in American society

1. Calvinist

C. Food preferences of people throughout history

1. Pres. Clinton

2. Romans

II. Nutty Nougat, other mixed versions

. People desperate for action

III. Caramels

. Sentimentality

1. Quote on card 7

IV. Nut bars

. The tough guy: peanuts and machismo

V. Solid chocolate bar

. High-minded? or

A. Repressed?

VI. Coconut bars

. Sometimes you feel like a nut?

1. Psychopaths and coconut

VII. Butter Krisp, toffee bars, Tasty Toffee

. Are they really classier than the rest of us?

VIII. The opposition, the idea of taste as personal issue

. Card 24, Dr. Faust says there is no connection, we all have free will

A. Card 26, Dr. Schmidt says taste changes over eras

IX. Rebuttal

. Swiss studies, television commercials

A. Fashion analogy

X. Conclusion: The connection between candy bars and personality cannot be ignored, and allows us all to know more about sugar and the world we live in, and the way it affects us.

Tim sets his paper down next to the ordered cards, places his books next to them, and takes a well-deserved break.

Step 5: Check your plan

When your outline is finished, you should have a paragraph-byparagraph plan of action. Do you know what each paragraph is to be about? Does each paragraph support your statement of purpose? If the topic of the paper is in the form of a question, does your outline answer it? When you can answer yes to these questions, you are officially ready to write.

Step 6: Write a rough draft

Many writers prefer to leave the writing of their introductory paragraph till the end, when they know exactly what they will be introducing. You probably want to start writing the paragraph that will follow the introduction, the paragraph in which you begin discussion of the topic. Here, your research index cards will come in handy. You already have your cards organized for each paragraph; now use them, making clear your quotes and paraphrases with footnotes, and presenting the findings of all that research. Follow your outline carefully, going paragraph by paragraph, keeping your cards in order for easy reference by the end. Give yourself plenty of time; burnout and exhaustion lead to sloppy writing. When you get to the end you can write your introductory and conclusive paragraphs, which will be fairly similar.

Step 7: Take a break (or a day off), then reread and edit the paper

Once you have written your paper according to the form of your outline, you have what is known as the first draft. You will probably want to take a day off after finishing the first draft to give yourself some breathing room before you come back to edit it. Make sure one paragraph flows smoothly to the next. Make sure you have given credit where credit is due. When paraphrasing or quoting you MUST credit the source, inserting footnotes as you go along.

Questions to ask when you are editing your paper

· Do I make a convincing case for my point?

· Do I present the story of whatever I’m describing in an interesting and engaging manner?

· Are both my arguments and the opposition’s arguments clearly presented?

· Does each paragraph serve a clear function either in describing the phenomenon or arguing the case?

· Do the sentences flow logically?

· Does each sentence serve a clear function in its paragraph?

If you find an unnecessary paragraph or sentence, eliminate it. If you have not made your point, look to find where you have strayed from your outline. Rewrite any illogical sentences. If you have a trusted friend, you may want to have her read it. This is all a lot of work, but it is work that is absolutely essential for a good paper. Also check for misspellings and grammatical mistakes. Make sure you read your paper through at least twice, correcting errors as you go along. Once you have edited and cleaned up any errors, you are ready for the final touches.

Editing Drill

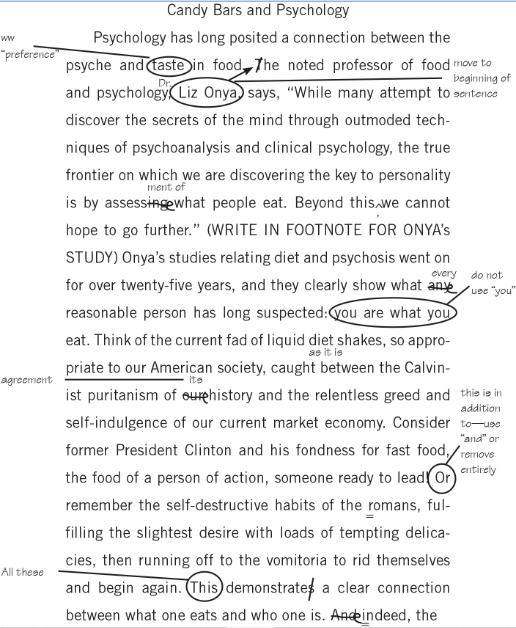

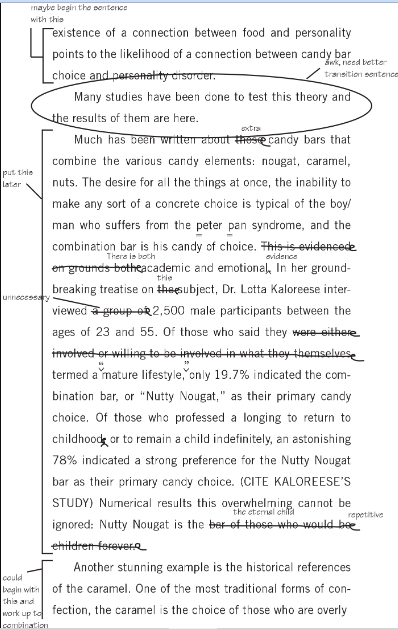

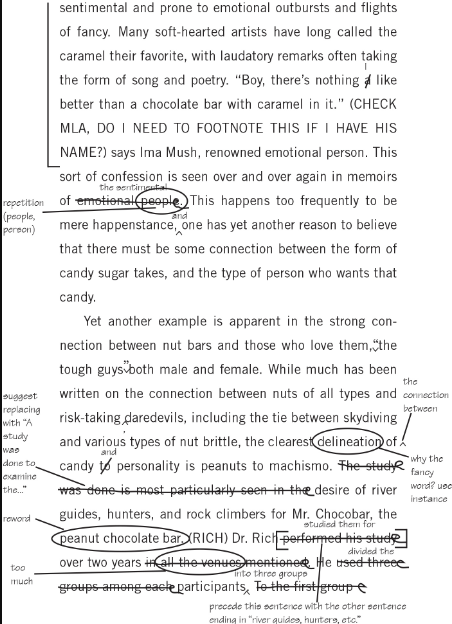

Edit Tim’s five-page paper, referring back to the editing guidelines in Chapter 4. Then compare your edits with ours in the section following this paper.

Candy Bars and Psychology

Psychology has long posited a connection between the psyche and taste in food. The noted professor of food and psychology, Liz Onya, says, “While many attempt to discover the secrets of the mind through outmoded techniques of psychoanalysis and clinical psychology, the true frontier on which we are discovering the key to personality is by assessing what people eat. Beyond this we cannot hope to go further.” (WRITE IN FOOTNOTE FOR ONYA’s STUDY) Onya’s studies relating diet and psychosis went on for over twenty-five years, and they clearly show what any reasonable person has long suspected: you are what you eat. Think of the current fad of liquid diet shakes, so appropriate to our American society, caught between the Calvinist puritanism of our history and the relentless greed and self-indulgence of our current market economy. Consider former President Clinton and his fondness for fast food, the food of a person of action, someone ready to lead! Or remember the self-destructive habits of the romans, ful-filling the slightest desire with loads of tempting delicacies, then running off to the vomitoria to rid themselves and begin again. This demonstrates a clear connection between what one eats and who one is. And indeed, the existence of a connection between food and personality points to the likelihood of a connection between candy bar choice and personality disorder.

Many studies have been done to test this theory and the results of them are here.

Much has been written about those candy bars that combine the various candy elements: nougat, caramel, nuts. The desire for all the things at once, the inability to make any sort of a concrete choice is typical of the boy/man who suffers from the peter pan syndrome, and the combination bar is his candy of choice. This is evidenced on grounds both academic and emotional. In her ground-breaking treatise on the subject, Dr. Lotta Kaloreese interviewed a group of 2,500 male participants between the ages of 23 and 55. Of those who said they were either involved or willing to be involved in what they themselves termed a mature lifestyle, only 19.7% indicated the combination bar, or “Nutty Nougat,” as their primary candy choice. Of those who professed a longing to return to childhood, or to remain a child indefinitely, an astonishing 78% indicated a strong preference for the Nutty Nougat bar as their primary candy choice. (CITE KALOREESE’S STUDY) Numerical results this overwhelming cannot be ignored: Nutty Nougat is the bar of those who would be children forever.

Another stunning example is the historical references of the caramel. One of the most traditional forms of confection, the caramel is the choice of those who are overly sentimental and prone to emotional outbursts and flights of fancy. Many soft-hearted artists have long called the caramel their favorite, with laudatory remarks often taking the form of song and poetry. “Boy, there’s nothing a like better than a chocolate bar with caramel in it.” (CHECK MLA, DO I NEED TO FOOTNOTE THIS IF I HAVE HIS NAME?) says Ima Mush, renowned emotional person. This sort of confession is seen over and over again in memoirs of emotional people. This happens too frequently to be mere happenstance, one has yet another reason to believe that there must be some connection between the form of candy sugar takes, and the type of person who wants that candy.

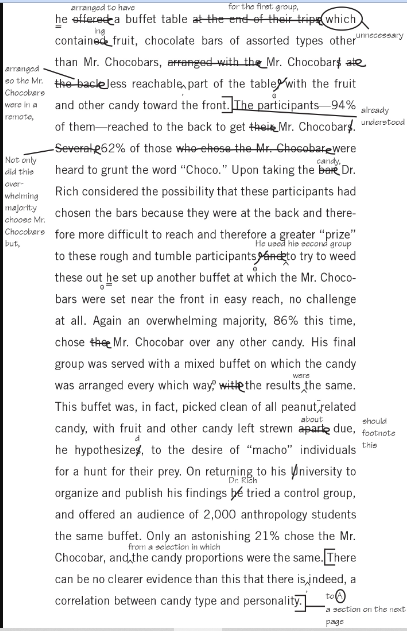

Yet another example is apparent in the strong connection between nut bars and those who love them, the tough guys both male and female. While much has been written on the connection between nuts of all types and risk-taking daredevils, including the tie between skydiving and various types of nut brittle, the clearest delineation of candy to personality is peanuts to machismo. The study was done is most particularly seen in the desire of river guides, hunters, and rock climbers for Mr. Chocobar, the peanut chocolate bar. (RICH) Dr. Rich performed his study over two years in all the venues mentioned. He used three groups among each participants. To the first group he offered a buffet table at the end of their trips which contained fruit, chocolate bars of assorted types other than Mr. Chocobars, arranged with the Mr. Chocobars at the back less reachable part of the table, with the fruit and other candy toward the front. The participants—94% of them—reached to the back to get their Mr. Chocobars. Several, 62% of those who chose the Mr. Chocobar, were heard to grunt the word “Choco.” Upon taking the bar. Dr. Rich considered the possibility that these participants had chosen the bars because they were at the back and therefore more difficult to reach and therefore a greater “prize” to these rough and tumble participants, and to try to weed these out he set up another buffet at which the Mr. Chocobars were set near the front in easy reach, no challenge at all. Again an overwhelming majority, 86% this time, chose the Mr. Chocobar over any other candy. His final group was served with a mixed buffet on which the candy was arranged every which way, with the results the same. This buffet was, in fact, picked clean of all peanut related candy, with fruit and other candy left strewn apart, due, he hypothesizes, to the desire of “macho” individuals for a hunt for their prey. On returning to his University to organize and publish his findings he tried a control group, and offered an audience of 2,000 anthropology students the same buffet. Only an astonishing 21% chose the Mr. Chocobar, and the candy proportions were the same. There can be no clearer evidence than this that there is indeed, a correlation between candy type and personality.

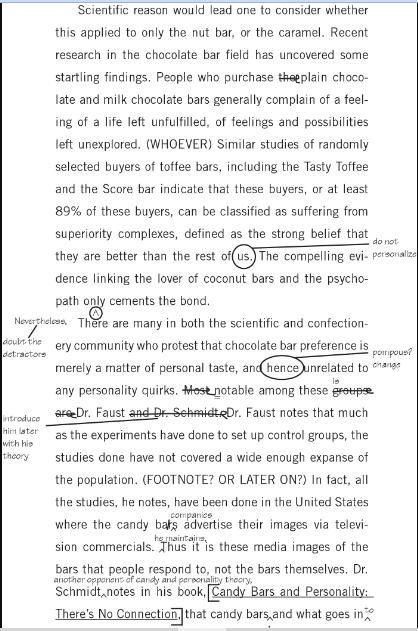

Scientific reason would lead one to consider whether this applied to only the nut bar, or the caramel. Recent research in the chocolate bar field has uncovered some startling findings. People who purchase the plain chocolate and milk chocolate bars generally complain of a feeling of a life left unfulfilled, of feelings and possibilities left unexplored. (WHOEVER) Similar studies of randomly selected buyers of toffee bars, including the Tasty Toffee and the Score bar indicate that these buyers, or at least 89% of these buyers, can be classified as suffering from superiority complexes, defined as the strong belief that they are better than the rest of us. The compelling evidence linking the lover of coconut bars and the psychopath only cements the bond.

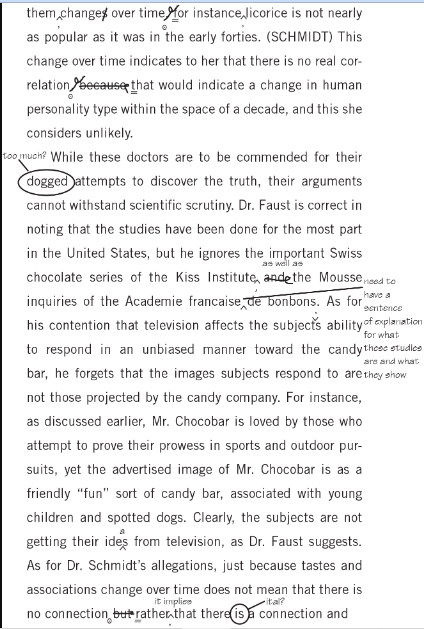

There are many in both the scientific and confectionery community who protest that chocolate bar preference is merely a matter of personal taste, and hence unrelated to any personality quirks. Most notable among these groups are Dr. Faust and Dr. Schmidt. Dr. Faust notes that much as the experiments have done to set up control groups, the studies done have not covered a wide enough expanse of the population. (FOOTNOTE? OR LATER ON?) In fact, all the studies, he notes, have been done in the United States where the candy bars advertise their images via television commercials. Thus it is these media images of the bars that people respond to, not the bars themselves. Dr. Schmidt notes in his book, Candy Bars and Personality: There’s No Connection, that candy bars and what goes in them changes over time, for instance licorice is not nearly as popular as it was in the early forties. (SCHMIDT) This change over time indicates to her that there is no real correlation, because that would indicate a change in human personality type within the space of a decade, and this she considers unlikely.

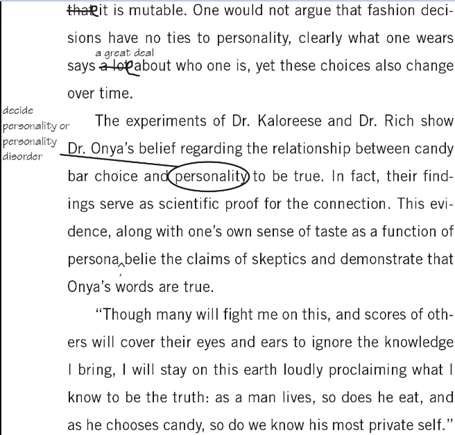

While these doctors are to be commended for their dogged attempts to discover the truth, their arguments cannot withstand scientific scrutiny. Dr. Faust is correct in noting that the studies have been done for the most part in the United States, but he ignores the important Swiss chocolate series of the Kiss Institute and the Mousse inquiries of the Academie francaise de bonbons. As for his contention that television affects the subjects ability to respond in an unbiased manner toward the candy bar, he forgets that the images subjects respond to are not those projected by the candy company. For instance, as discussed earlier, Mr. Chocobar is loved by those who attempt to prove their prowess in sports and outdoor pursuits, yet the advertised image of Mr. Chocobar is as a friendly “fun” sort of candy bar, associated with young children and spotted dogs. Clearly, the subjects are not getting their ides from television, as Dr. Faust suggests. As for Dr. Schmidt’s allegations, just because tastes and associations change over time does not mean that there is no connection but rather that there is a connection and that it is mutable. One would not argue that fashion decisions have no ties to personality, clearly what one wears says a lot about who one is, yet these choices also change over time.

The experiments of Dr. Kaloreese and Dr. Rich show Dr. Onya’s belief regarding the relationship between candy bar choice and personality to be true. In fact, their findings serve as scientific proof for the connection. This evidence, along with one’s own sense of taste as a function of persona belie the claims of skeptics and demonstrate that Onya’s words are true.

“Though many will fight me on this, and scores of others will cover their eyes and ears to ignore the knowledge I bring, I will stay on this earth loudly proclaiming what I know to be the truth: as a man lives, so does he eat, and as he chooses candy, so do we know his most private self.”

Our version, with edits

Here is the version marked with the edits we thought were necessary. Are they the same as your edits? Don’t worry if they aren’t, but check for differences to see the reasoning behind them.

Once you have made all the edits, both organizational and stylistic, you are ready to put your paper into its final stages, complete with reference and format specifications. This work is mostly mechanical, but it does require that you pay close attention to minute details. The end is in sight, but don’t let that allow you a sloppy finish.

Step 8: Create a bibliography

A bibliography is the list of references used in the writing of a paper. Compile your bibliography according to the rules of whatever style guide you are using, whether MLA, APA, or Chicago. Citation style is usually determined by your instructor, so be sure to ask if you’re not sure! Note that in the final draft of Tim’s research paper beginning on the next page, Chicago style is used.

Step 9: Title your paper

Finally, when the rest of the paper is sitting on your desk all clean and edited with bibliography, you can create a title. For some reason, academic papers tend to have titles with colons in them.

Spiderman: Arachnid or Anarchist?

Stalin, Hitler, and Mussolini:

People I’m Glad I Didn’t Know

And so forth. Your title should indicate the subject of your paper in a pithy manner, and, if possible, be eye-catching. Don’t be afraid to have some fun with this; it’s the part of your paper your teacher sees first and should be as interesting as you can make it.

Step 10: Write your final draft

Sometimes You Feel Like A Nut, Sometimes You Don’t:

Candy Bars and the Psychology of Taste

by Tim

Psychology has long posited a connection between the psyche and food preferences. Noted professor of food and psychology Liz Onya says, “While many attempt to discover the secrets of the mind through outmoded techniques of psychoanalysis and clinical psychology, the true frontier on which we are discovering the key to personality is an assessment of what people eat.”1 Onya’s studies relating diet and psychosis went on for over twenty-five years, and they clearly show what every reasonable person has long suspected: one is what one eats. Think of the current fad of liquid diet shakes, so appropriate to American society, caught as it is between the Calvinist puritanism of its history and the relentless greed and self-indulgence of its current market economy. Consider former President Clinton and his fondness for fast food, the food of a person of action, someone ready to lead! Remember the self-destructive habits of the Romans, fulfilling the slightest desire with loads of tempting delicacies, then running off to the vomitoria to rid themselves and begin again. All these demonstrate a clear connection between what one eats and who one is. Further, the existence of a connection between food and personality points to the likelihood of a connection between candy bar choice and personality disorder.

This theory has been tested time and time again, and the results of these tests coincide: there is a connection. One of the earliest such studies explored the historical references of the caramel. Perhaps the most traditional form of confection, the caramel is the choice of those who are overly sentimental and prone to emotional outbursts and flights of fancy. Many soft-hearted artists have long called the caramel their favorite, with laudatory remarks often taking the form of song and poetry. “Boy, there’s nothing I like better than a chocolate bar with caramel in it.”2 says Ima Mush, renowned emotional person. This sort of confession is seen over and over again in memoirs of emotional people. This happens too frequently to be mere happenstance, yet another reason to believe that there must be some connection between the form of candy sugar takes, and the type of person who wants that candy.

Much has also been written about candy bars that combine the various candy elements: nougat, caramel, nuts. The desire for all things at once, the inability to make any sort of a concrete choice is typical of the boy/man who suffers from the Peter Pan syndrome, and the combination bar is his candy of choice. There is both academic and emotional evidence. In her ground-breaking treatise on this subject, Dr. Lotta Kaloreese interviewed 2,500 male participants between the ages of 23 and 55. Of those who said they lived what they termed a “mature lifestyle,” only 19.7% indicated the combination bar, or “Nutty Nougat,” as their primary candy choice. Of those who professed a longing to return to childhood or to remain a child indefinitely, an astonishing 78% indicated a strong preference for the Nutty Nougat bar as their primary candy choice.3 Numerical results this overwhelming cannot be ignored: Nutty Nougat is the bar of the eternal child.

Yet another example is apparent in the strong connection between nut bars and those who love them, the “tough guys,” both male and female. While much has been written on the connection between nuts of all types and risk-taking daredevils, including the tie between skydiving and various types of nut brittle, the clearest instance of candy’s connection to personality is the tie between peanuts and machismo. A study was commissioned to examine the common desire among river guides, hunters, and rock climbers for the Mr. Chocobar, a chocolate bar with peanuts.4 Dr. Rich divided the participants into three groups and studied them over two years. He arranged to have a buffet table for the first group, containing fruit and chocolate bars of assorted types, including Mr. Chocobars. He designed the buffet so the Mr. Chocobars were in a remote, less reachable part of the table. The participants—94% of them—reached to the back to get a Mr. Chocobar. Not only did this overwhelming majority select Mr. Chocobar, but 62% of those who chose the Mr. Chocobar were heard to grunt the word “Choco” upon taking the candy. Dr. Rich considered the possibility that these participants had chosen the bars because they were at the back and more difficult to reach, therefore a greater “prize” to these rough-and-tumble participants. He used his second group to try to weed these out. He set up another buffet at which the Mr. Chocobars were set near the front in easy reach, no challenge at all. Again an overwhelming majority, 86% this time, chose Mr. Chocobar over any other candy. His final group was served with a mixed buffet on which the candy was arranged every which way, and the results were the same. This buffet was, in fact, picked clean of all peanut-related candy, with fruit and other candy left strewn about, due, he hypothesized, to the desire of “macho” individuals for a hunt for their prey. On returning to his university to organize and publish his findings, Dr. Rich examined a control group. He offered an audience of 2,000 anthropology students the same buffet. Only 21% chose the Mr. Chocobar from a selection in which the candy proportions were the same.

Scientific curiosity would lead one to consider whether this connection between personality and preference applied only to the nut bar and the caramel. Recent research in the chocolate bar field has uncovered some startling findings. People who purchase plain chocolate and milk chocolate bars generally complain of a feeling of a life left unfulfilled, of feelings and possibilities left unexplored.5 Similar studies of randomly selected buyers of toffee bars, including the Tasty Toffee and the Score bar, indicate that at least 89% of these buyers suffer from superiority complexes, defined as the strong belief that they are better than the rest of the population. The compelling evidence linking the lover of coconut bars and the psychopath only cements the bond. There can be no clearer evidence than this that there is, indeed, a correlation between candy type and personality.

Nevertheless, there are many in both the scientific and confectionery communities who protest that chocolate bar preference is merely a matter of personal taste, and therefore unrelated to any personality quirks. Notable among these is Dr. Faust. Dr. Faust notes that, much as the experimenters have tried to set up control groups, none of the studies have covered a wide enough expanse of the population.6 Furthermore, Dr. Faust adds, the studies have all been conducted in the United States, where the candy bar companies advertise their images via television commercials. Thus, he maintains, people in the United States respond to these media images, not to the bars themselves. Dr. Schmidt, another opponent of candy-personality theory, notes in her book Candy Bars and Personality: There’s No Connection that candy bars, and what goes into them, change over time. For instance, licorice is not nearly as popular as it was in the early forties.7 This change over time indicates to her that there is no real correlation, because that would indicate a change in human personality type within the space of a century, and this she considers unlikely.

While Faust and Schmidt are to be commended for their dogged attempts to discover the truth, their arguments cannot withstand scientific scrutiny. Dr. Faust is correct in noting that the studies have been conducted for the most part in the United States, but he ignores the important Swiss chocolate series of the Kiss Institute, as well as the Mousse inquiries of the Académie francaise de bonbons.8 The Kiss Institute found the same superiority connection referred to earlier, displayed by over 500 participants from France, Switzerland, and Germany. The Mousse inquiries provided convincing evidence for the claim that various forms of mousse can be used in the treatment of many types of neuroses, establishing another clear connection between the psyche and chocolate. As for Dr. Faust’s contention that television affects the subject’s ability to respond in an unbiased manner toward the candy bar, he does not consider that the images projected by the candy company are unrelated to the interests and aspirations of the candy devotees. For instance, as discussed earlier, Mr. Chocobar is loved by those who attempt to prove their prowess in sports and outdoor pursuits, yet the advertised image of Mr. Chocobar is as a friendly “fun” sort of candy bar, associated with young children and spotted dogs. Clearly, the subjects are not getting their ideas from television, though Dr. Faust believes otherwise. As for Dr. Pheelgud’s allegations, just because tastes and associations change over time does not mean that there is no connection between the two. It implies, rather, that there is a connection and it is mutable. One would not argue that fashion decisions have no ties to personality, clearly what one wears says a great deal about who one is, yet these choices also change over time.

The experiments of Dr. Kaloreese and Dr. Rich show Dr. Onya’s belief regarding the relationship between candy bar choice and personality to be true. In fact, their findings serve as scientific proof for the connection. This evidence, along with one’s own sense of taste as a function of persona, belie the claims of skeptics and demonstrate the truth of Onya’s words. “Though many will fight me on this, and scores of others will cover their eyes and ears to ignore the knowledge I bring, I will stay on this earth loudly proclaiming what I know to be the truth: as a man lives, so does he eat, and as he chooses candy, so do we know his most private self.”9

Bibliography

Faust, Goethe. “I’d Sell My Soul to Publish a Book About Candy. In Dubious Arguments. Chicago: Arguers Anonymous Press, 1998.

Onya, Liz. Let’s Eat Some More. New York: Glutton & Sons, 1994.

Kaloreese, Lotta. “Men Who Would Be Children.” In Experiments in Chocolate. Edited by Russell Upsom Grubb. Pennsylvania: Bar Press, 1991.

Mush, Ima. Notes on a Sentimental Life. Hawaii: Soft Hearts & Company, 1993.

Phat, Hy. “The Life I Could Have Had: Plain Chocolate and the Repressed.” In Watchamacallit and Aphasia: An Introduction to Chocolate and Mental Health. Edited by Roland Butter. Arizona: Bench Press, 1992.

Schmidt, I. Candy Bars And Personality: There’s No Connection. New York: Skeptics & Co., 1988.

Rich, Tu. Peanuts And Machismo: I Know They Are Connected. Texas: Men Don’t Press, 1993.

Swiss, Miss. The Mousse Inquiries. Switzerland: Braids & Company, 1962.

Whipt, I. M. “An Important Study.” Nougat Quarterly, 103 (1987), 12—34.

Common research paper pitfalls

Getting bogged down in an organizational swamp

The organizing process may take you quite a while, and there is the temptation to say to yourself, “I’ve been working on this paper organization for four hours and I haven’t written a thing! This is awful!” Relax. Thinking through your paper is an important step of writing.

Nonetheless, don’t get caught in the endless note-taking trap. A pleasant rule of thumb: the length of your notes should not exceed the length of your paper. If you find yourself buying a second package of 100 index cards, you’ve gone overboard; reign yourself in, organize the cards, and start writing.

Writing before the research is done

Finish your research before you start writing, because you never know if something you find will prove your thesis wrong or right. The research process helps you know what you want to write. Writing before your research is finished is like constructing a building before the blueprint has been drawn.

Procrastinating

With an organized outlook and meticulous research you can write a term paper in less time than you might think. Nevertheless, you should still allow yourself at least one week for every five pages. Trying to write the paper in one night will, in most cases, ensure that you produce a paper that is poorly written and conceptually crippled. You’ve probably heard of the all-nighter, as in, “I stayed up all night and wrote the whole paper in five hours and then I got an A.” For some people, that may be possible, but for most of us, it leads only to incoherent, sloppy writing. If you are the type to procrastinate, set up a written schedule giving yourself due dates for your research, your outlines, your first five pages, etc. Then give it to someone who you trust will bug you enough to remind you but not enough so you will never forgive her.

Striving for perfection

“What?” you say, “Perfection a pitfall?”

Here’s the situation: If you try to make every sentence that you write perfect as you write it, the odds are that you will never get your paper written. You will have the opportunity to edit your paper later. The purpose of the paper is to present your thesis and your research, not to write a literary masterpiece. Get your paper written in rough draft and then attempt perfection, or you will end up writing the first sentence for the rest of your life.

Plagiarism

Don’t take credit for someone else’s work, fake footnotes, or fake research. Your instructor will be able to discern original work from plagiarized work, and you will have to face the consequences.

Focusing on quantity over quality

It is tempting, sometimes, to ramble on for pages and pages because you believe your paper has to achieve a certain length. Say what you mean to say and no more; any unnecessary sentences will only weaken your paper. Your paper should be long enough to cover your topic, and once you have covered it, finish. Pieces that don’t belong will stick out and destabilize the structure you have invested so much time in building.

Formatting and citations

Since term papers are all about research, you must indicate the sources of your research within your paper. This is done with footnotes (or endnotes), references within the text, and a bibliography or works cited page. Follow the style guide specified by your instructor. The main ones are MLA, APA, and Chicago.

There are some rules to follow when including references within a paper.

Quotations

Any quotation you use in your paper should be copied exactly as it appears in the original source and cited appropriately. If you must shorten a quotation, indicate that sections were removed by using the ellipses, those three dots “…” which translate to “Something has been omitted here.”

Quotations of fewer than four typed lines should be placed within quotation marks and introduced by a comma or a colon. Quotations of four typed lines or longer are also introduced by a comma or a colon, but are set off from the text by triple spacing, and indented five lines on either side; they can also be single-spaced.

Footnotes and endnotes

They are ordered references indicated by a superscript number after a paraphrase or quotation that is not your own.10 These references should be used only when necessary. Useless quotes used to pad the length will be spotted, and notes that have been fractured to provide a higher number of notes will weaken your writing. Footnotes are written at the bottom of the page on which the reference appears, endnotes are given on a separate page at the end of the paper.

Footnotes and endnotes serve the same purpose; the format you use depends on your teacher’s preference.

In the body of your paper:

The difference between owning a dog and owning a cat is simple: “dogs have masters; cats have staff.”1

Let’s say you’re following Chicago style. The footnote would look like this:

1 Kitty Lovah, “Cats Rule and Dogs Drool,” in The Ascendant Feline (New York: Random Place, 1998), 61.

If you continue with references to the same book, you can repeat the author’s last name and show the new page.

2 Lovah, 117—118.

If you have used two different books by the same author, you can repeat the author’s last name, and the title or an abbreviation of the title, and then the page number(s). Like this:

3 Lovah, Canine Subordination, 56.

There are endless variations on note format, for articles in periodicals, books with multiple authors, and so on. The basic rule is that the author’s name is given first; the book title is italicized; an article or section of a book is put in quotation marks; and the publication information is given.

References within text

These are used only in papers with very few references. Basically, include all the information you would have written in the footnote, as we just did.

Bibliography

A bibliography is a list of all the works used in compiling a research paper. If you have used a book or article for information, it belongs in your bibliography, even if you have not directly cited it. Do not list books you did not use, no matter how fancy you want to appear. If you have used footnotes or endnotes, you should list the works in alphabetical order without numbers. If you have used references within the text, number your entries.

Bibliographical entries are constructed differently from footnotes. Here is what a bibliography should look like, again using Chicago style.

Lebowitz, Fran. Social Studies. New York: Random House, 1977.

Title

Don’t underline, capitalize, or do anything else fancy to the title of your research paper. You can have a title page if you want one, but it is not necessary.

Page numbers

Do not count the title page, if you include one, in the page count. The page count starts on the first page, but you don’t write down the page number until the second page. This is because we assume the reader knows that the first page he is reading is, in fact, the first page.

Italics and quotation marks

Titles of books, plays, and long poems get italics. If you have no italics, underline. Titles of shorter pieces get put in quotation marks.

In conclusion…

Research papers aren’t so terrible; they just call for a detailed plan of attack and a structured schedule. Writing a research paper is much like writing any other academic or non-personal essay. If you ever get stuck and don’t know what to write next, ask yourself, “What am I trying to say?” and write that down. That is the surest way to clear, direct communication through writing.

Recommended reading

These books are not generally fun to read, except The Elements of Style, but they contain useful information for writing research papers.

Guide to Reference Books, American Library Association.

MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations, Modern Language Association.

William Strunk and E. B. White, The Elements of Style, Macmillan.

1 Liz Onya, Let’s Eat Some More (New York: Glutton & Sons, 1994), 107.

2 Ima Mush, Notes on a Sentimental Life (Hawaii: Soft Hearts & Company, 1993), 21.

3 Lotta Kaloreese, “Men Who Would Be Children” in Experiments in Chocolate, ed. Russell Upsom Grubb (Pennsylvania: Bar Press, 1991), 32—45.

4 Tu Rich, Peanuts and Machismo (Texas: Men Don’t Press, 1993), 10.

5 Hy Phat, “The Life I Could Have Had: Plain Chocolate and the Repressed” in Watchamacallit and Aphasia: A Journal of Chocolate and Mental Health, ed. Roland Butter (Arizona: Bench Press, 1992).

6 Goethe Faust, “I’d Sell My Soul to Publish a Book About Candy” in Dubious Arguments (Chicago: Arguers Anonymous Press, 1998), 14—23.

7 I. Schmidt, Candy Bars and Personality: There’s No Connection (New York: Skeptics & Company, 1988), 34—35.

8 Miss Swiss, The Mousse Inquiries (Switzerland: Braids & Company, 1962).

9 Onya, 72.

10 It looks just like this.