Student's guide to writing college papers, Fourth edition - Kate L. Turabian 2010

How researchers think about their answers/arguments

What researchers do and how they think about it

Writing your paper

Students are often surprised to realize that what they had thought was the main job of research—looking up information on a topic—is a small part of a successful research project. Before you start looking things up, you have to find a good research question to guide your reading and note taking: what you look for is information that will support and/or test an answer to that question. But once you think you have found an answer, your work has just begun. Readers won't accept that answer just because you believe it: you have to give them good reasons to believe it too. And they won't just take your word that your reasons are good ones: you have to support each reason with reliable evidence. In short, readers expect you to offer a complete and convincing argument that uses the information you have found to explain and support your answer.

1.3.1 Think of Your Readers as Allies, Not Opponents

By argument, we do not mean anything like the heated exchanges you see on TV or among your friends, where anything goes because all anyone cares about is winning. Unfortunately, many students imagine all arguments are like that, partly because the loud and angry ones are so memorable but also because the language we use to describe argument makes it sound like combat:

I will defend my position from the attack of my opposition; then I will marshal my most powerful evidence to counterattack. I'll probe for weak spots in the other position, so that I can undermine it and knock down its key claims. We will fire away at each other until one or the other of us gives up and surrenders, leaving only the victor and the vanquished.

Experienced researchers know that they would be foolish to treat readers like enemies to be vanquished. To succeed, a researcher must enlist readers as allies who agree to do or think what the researcher claims they should. If you hope to win over your readers, you must adopt a stance that encourages them not to be defensive but receptive, because you treat their views, beliefs, and questions with respect. That does not mean telling them only what they already believe or want to hear—after all, your ultimate goal is to change their minds. But you do have to attend closely to what you know (or imagine) your readers already believe, so that you can move them from where they are to where your new claim would lead them.

CAUTION

Don't Pander to Teachers

Many students are rewarded in high school for writing papers that tell teachers what they want to hear by repeating what the teacher has already said. But that can be a grave mistake in college: it bores your teachers, who think it is not enough that you just rehash what's said in class and in the readings. They want to see not only that you know the class material but that you can use that knowledge to think for yourself. If your papers, especially your research papers, merely summarize what you've read or repeat back your teacher's ideas, you will get that dreaded comment: This does not go far enough.

When your teacher says that you must make an argument to support your answer, don't think of having an argument, in which everyone battles for their position and no one changes their minds. Instead, imagine an intense, yet amiable conversation with people who want to find a good answer to your question as much or even more than you do. They don't want to hear about your opinions but about reasoned claims you can support. They want to know what reasons led you to your claim and what evidence makes you think those reasons are true. Because this is a conversation, they'll expect you to consider their point of view and to address any questions or concerns they might have. And they'll expect you to be forthcoming about any gaps in your argument or complications in your evidence. In short, they want you to work with them to achieve the best available answer, not for all time but for now.

1.3.2 Think of Your Argument as Answers to Readers' Questions

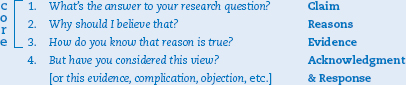

To create that kind of argument, you will have to answer the questions that any rational person would ask whenever you ask them to do or believe something new. Each answer corresponds to one of the parts of argument.

1.3.2.1 The Core of an Argument: Claim + Reasons + Evidence

Your answers to the first three questions constitute the core of your argument.

1. Claim: What's the answer to your question? Once you raise your research question, readers naturally want to know the answer. That answer is what you claim and then support.

Although many people think that black musical artists of the 1950s and 1960s were harmed when white performers “covered” black records by creating their own versions to sell to white audiences, I claim that the practice of racial covering actually helped the original artists more than it harmed them.claim

2. Reasons: Why should I believe that? Unless your answer is obvious (in which case, the question was not worth asking), readers will not accept it at face value. They'll want to know why they should accept your claim as true.

Although . . ., I claim that the practice of racial covering actually helped the original artists more than it harmed them claim because without covers white teens would not have heard or bought the original recordings,reason 1 because covers gave white audiences a taste for blues, R&B, and gospel,reason 2 and because white teens then began to seek out the work of black performers.reason 3

3. Evidence: How do you know that? Even when your reasons seem plausible, responsible readers won't accept them just on your say-so. They expect you to ground each reason in the factual evidence you collect from sources.

Although . . ., I claim that . . .claim because. . . .reasons My evidence that white teens would not have heard or bought the original recordings is as follows: [sales statistics, information on record distribution and radio play, quotations from performers and producers at the time, etc.].evidence for reason 1

1.3.2.2 Acknowledging Readers' Voices

You'll have the basis for a sound argument once you can offer readers a claim that answers your question, reasons to believe that they should accept your claim, and evidence showing that those reasons are true. These three elements make up the core of every argument. But if you offer only the reasons and evidence that you think support your claim, thoughtful readers may feel that you have not dealt with them fairly. They want to know not only what you found that supports your claim, but also what you found that might work against, or at least complicate it—especially if they have views that are different from yours.

So in addition to the reasons and evidence that you pull together to support your claim, you should answer questions that might seem to challenge it:

4. Acknowledgment and Response: But what about this other view? You cannot expect your readers to think exactly as you do. They will know things you don't, they will believe things you don't, and they may even distrust the kind of argument you want to make. If you adopt a genuinely cooperative stance, then you are obliged to acknowledge and respond to at least some of the questions that arise because of those differences.

I claim that. . . .claim + reasons + evidence To be sure, there were many elements of exploitation in racial covering. The white performers, not the black artists, received the money and fame. And many artists of the 1950s never received any of the benefits that came later.acknowledgment But covers helped to bring about a situation in which black artists are among our most popular, influential, and wealthy pop musicians.response

1.3.2.3 Explaining Your Logic

In some cases, researchers make arguments in which they have to explain not only their reasons and evidence, but their principles of reasoning. Suppose, for example, you were visiting your friend Paul in Cajun country. It is a warm July evening, so he invites you to go for a walk on the levee, and then he adds, “You might want to put on long sleeves.” This makes no sense, so you ask, “Why?” “Because the sun's going down,” he replies. Now you are truly baffled. You understand Paul's claim, and you can see the sun going down. But you just cannot understand why that means you should wear long sleeves on a warm July night. His reason is true, and his evidence is good. But his argument so far fails.

That's when we need a warrant, when readers understand our claim and accept our reason and evidence, but do not see why the reason (the sun going down) supports the claim (you need long sleeves). So now you ask again: “Why does the sun doing down mean that I need long sleeves?” As it happens, Paul has a good answer in the form of a warrant: “Ah,” he says. “You don't know about swamp country. When the sun goes down, the mosquitoes come out. If you don't cover up, they will eat you alive.”

Now it all makes sense. As an expert in swamp-country living, Paul knew a principle of reasoning that you did not: When the sun goes down, you should protect your skin from mosquitoes. Once you learn the principle, you can accept the claim (though you might wonder why anyone would go walking among mosquitoes that want to eat you alive).

A warrant states a principle of reasoning of the form: When this condition is true, we can draw this conclusion. They are used most often when an expert (Paul) makes an argument about something he knows well (swamp-country living) for someone who is not an expert (you). The expert (Paul) needs a warrant if the non-expert (you) understands a claim (put on long sleeves) and accepts the truth of its supporting reason (the sun is going down) but doesn't see how the reason supports the claim. The warrant supplies the missing connection: “When the sun goes down, the mosquitoes come out, and you must protect your skin from bites. So wear long sleeves to protect your arms.”

5. Warrant: Why does that evidence support your claim? When readers see the world in ways that are very different from yours, they may not recognize what general principle of reasoning connects your reasons and your claims. This situation rarely arises when you write a paper for a class, but it might. For example, you would have to supply a warrant if some readers asked, But whydoes it matter that white teens would not have heard R&B without covers? How does that show that covers helped more than harmed black artists? To which you would have to reply with a general principle:

An artist benefits from any product that expands his audience for future sales, even if he makes no money off the sale of that product.warrant

For the most part, only advanced researchers need warrants, most often when experts write for readers who are not experts, when they use a new or controversial research method, or when they address a controversial issue. You probably won't have to explain your logic in a paper for a class, so we will not dwell on this fifth question. But you should know that readers might ask it.

1.3.3 Use the Parts of Argument to Guide Your Research

A research question helps guide your research because it tells you generally what information to look for: whatever is relevant to answering your question. But in the parts of argument you have an even better guide. As you search for and read your sources, remember that you will need information to answer at least four questions that every cooperative argument must address.

Plan Your Research Around the Questions of Argument

Every argument must answer the three questions that define the core of a research argument, and cooperative ones must also answer a fourth.

Create a plan to search for and read sources so that you have good answers to each of these questions:

1. Claim: If you begin without a plausible claim that answers your research question, start by reading general treatments of your topic in order to get ideas for possible answers.

2. Reasons: Once you have a claim that can serve as an hypothesis, make a list of the reasons why you think that claim is true. If you think of too few plausible reasons, do some more general reading. If you still can't find any, look for another claim.

3. Evidence: Once you have a list of reasons, search for specific data that might serve as evidence to support each one. Depending on the kind of reason, that evidence might be statistics, quotations, observations, or any other facts. If you cannot find evidence for a reason, then you have to replace that reason. If you find evidence that goes against a reason, keep the evidence. You may need to acknowledge it in your paper.

4. Acknowledgment & Response: As you read for claims, reasons, and evidence, keep a record of anything that might complicate or contradict your argument. You will need to acknowledge it if you think it might also occur to your readers.

We discuss these steps more fully in chapters 6 and 7.