Quick and dirty tips for better writing - Mignon Fogarty 2008

Chapter 1. Dirty words

Even though my show is called “Grammar Girl,” the secret is that it’s not usually grammar that confounds people—it’s usage. I get complaints from purists, but Usage Girl doesn’t have the same ring to it as Grammar Girl, and my books and podcasts aren’t for purists anyway—they’re for people who actually need help. Usage is about choosing the right word or phrase. It’s something teachers generally expect you to pick up on your own, and it’s the thing you’re most likely to get skewered for if you screw up. (Life is so unfair!) I don’t recall ever being taught the difference between affect and effect, for example; I was just expected to know.

Certain words are more difficult than others. I call them the dirty words, and we’re going to tackle them here.

AN HONORABLE CHALLENGE: A VERSUS AN

A lot of people learned the rule that you put a before words that start with consonants and an before words that start with vowels, but it’s actually a bit more complicated than that.

The actual rule is that you use a before words that start with a consonant sound and an before words that start with a vowel sound.

Squiggly waited for an hour.

Aardvark was on a historic expedition.

An hour is correct because hour starts with a vowel sound. People seem to most commonly get tripped up by words that start with the letters h and u because sometimes these words start with vowel sounds and sometimes they start with consonant sounds. For example, it is a historic expedition because historic starts with an h sound, but it is an honorable fellow because honorable starts with an o sound.

Squiggly had a Utopian idea.

Aardvark reminded him it’s an unfair world.

The letters o and m can be tricky too. Usually you put an before words that start with o, but sometimes you use a. For example, you would use a if you were to say, “She has a one-track mind,” because one-track starts with a w sound.

Squiggly wants to work as a missionary.

Aardvark wants to get an MBA.

Other letters can also be pronounced either way. Just remember it is the sound that governs whether you use a or an, not the first letter of the word.

Pronunciation Wars

Since pronunciation is what guides the choice between a and an, people in different regions, where pronunciations are different, can come to different conclusions about which is the appropriate word.

Many pronunciation differences exist between British and American English. For example, the word for a certain kind of plant is pronounced “erb” in American English and “her-b” in British English.

Even within the United States there can be regional pronunciation differences. Although the majority of people pronounce the h in historic, some people on the East Coast pronounce historic as “istoric” and thus argue that an historic monument is the correct form.

In the rare cases where this is a problem, use the form that will be expected in your country or by the majority of your readers.

Definitely!

A and an are called indefinite articles. The is called a definite article. The difference is that a and an don’t say anything special about the word that follows. For example, think about the sentence “I need a horse.” You’ll take any horse—just a horse will do. But if you say, “I need the horse,” then you want a specific horse. That’s why the is called a definite article—you want something definite. At least that’s how I remember the name.

Tweedle Thee and Tweedle Thuh

I find it interesting that there are two indefinite articles to choose from (a and an) depending on the word that comes next, but there is only one definite article (the). But there’s a special pronunciation rule about the that is similar to the rule about when to use a and an: The is pronounced “thuh” when it comes before a word that starts with a consonant sound, and it’s pronounced “thee” when it comes before a word that starts with a vowel sound. It can also be pronounced “thee” for emphasis, for example, if you wanted to say, “Twitter is the [pronounced “thee”] hot social networking tool.” I actually have trouble remembering this rule and have to make special marks in my podcast scripts to remind myself to get the pronunciation right. I think I must have missed the day they covered this in school, and I’ve never recovered.

A LOT OF TROUBLE: ALOT VERSUS A LOT

VERSUS ALLOT

The correct spelling is “a lot.”

Alot is not a word.

A lot means “a large number.”

Allot means “to parcel out.”

I WOULD NEVER AFFECT INTEREST JUST FOR

EFFECT: AFFECT VERSUS EFFECT

If you don’t know the difference between affect and effect, don’t worry—you’re not alone. These two words are consistently among the most searched for words in online dictionaries, and I get at least one e-mail message a week asking me to explain the difference. In fact, the confusion over affect and effect could be why impact has emerged to mean “affect” in business writing: people give up trying to figure out the difference between affect and effect and rewrite their sentences, unfortunately substituting an equally inappropriate word. (See “Impact,”.)

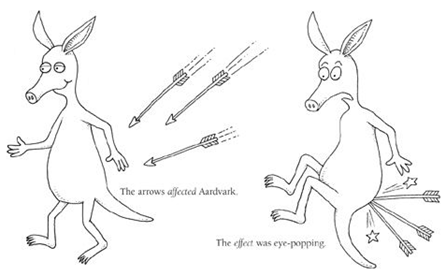

The difference between affect and effect is actually pretty straightforward: the majority of the time you use affect as a verb and effect as a noun.

Affect most commonly means something like “to influence” or “to change.”

The arrows affected Aardvark.

The rain affected Squiggly’s plans.

Affect can also mean, roughly, “to act in a way that you don’t feel,” as in He affected an air of superiority.

Effect has a lot of subtle meanings as a noun, but to me the meaning “a result” seems to be at the core of most of the definitions.

The effect was eye-popping.

The sound effects were amazing.

The rain had no effect on Squiggly’s plans.

So most of the time affect is a verb and effect is a noun. There are rare instances where the roles are switched, but this is “Quick and Dirty” grammar, not comprehensive grammar, and if you stick with the verb-noun rule, you’ll be right about 95 percent of the time.

An Effective Memory Trick

For our purposes, affect is a verb and effect is a noun. Now we can get to the memory tricks. First, get this image in your mind: the raven flew down the avenue. Why? Because the letters a-v-e-n (in both raven and avenue) are the same first letters as “affect verb effect noun”!

Need another one? Because effect is usually a noun, that means you can usually put an article in front of it and the sentence will still make sense. Look at these examples:

The effect is eye-popping.

He kissed her for [the] effect.

In both of these cases effect is a noun and you can put the in front of it without making the sentence completely weird. The isn’t necessary in the second example, but it doesn’t ruin the sentence. On the other hand, look at these sentences where affect is a verb:

The eye-popping arrow [the] affects everyone that way.

The kiss [the] affected her.

You can’t insert the direct article, the, before affect in those sentences, which means you want to use the verb (affect), not the noun (effect). I remember this rule by remembering that the ends with e and effect starts with e, so the two e’s butt up against each other.

The effect was eye-popping.

Exception Alert

Affect can be used as a noun when you are talking about psychology. It means the mood that someone appears to have. For example, a doctor may say, “The patient displayed a happy affect.” Psychologists find the word useful because they can never really know what someone else is feeling. Technically, they can only know how someone appears to be feeling.

Effect can be used as a verb that essentially means “to bring about,” or “to accomplish.” For example, you could say, “Aardvark hoped to effect change within the burrow.”

ALTHOUGH IT’S NOT A REAL RULE, IT STILL

BOTHERS ME: ALTHOUGH VERSUS WHILE

I often have to tell people their pet peeves aren’t actually hard-and-fast grammar rules. I have to tell people it’s OK to split infinitives, and in some cases it’s fine to end a sentence with a preposition.

I know it’s upsetting to find out your nearest and dearest beliefs are wrong because I have my own mistaken pet peeve: it bugs me no end when people use while to mean although, but however hard I looked, I couldn’t convince myself I was right. The horror!

You see, I believe although means “in spite of the fact that,” as in Although the tree was tall, Squiggly and Aardvark thought they could make it to the top. Although is what’s called a concessive conjunction, meaning that it is used to express a concession. On the other hand, I believe that while should be reserved to mean “at the same time,” as in While Squiggly gathered wood, Aardvark hid the maracas.

At first I was sure I was right because Eric Partridge said in his book Usage and Abusage that “while for although is a perverted use of the correct sense of while, which properly means ’at the same time.’ ”

Ha!

But then I discovered that Fowler’s Modern English Usage states it is normal and acceptable to use while to mean “although.” Fowler even called Partridge’s comment “indefensible.” It’s a grammar rumble, people.

I decided to go over their heads and see what the Oxford English Dictionary has to say, and it backs up Fowler with an entry stating that while can mean “although.” Two additional dictionaries concurred. I was thwarted, but I’d given it a good shot.

One reason I’m telling you this story is that I want you to know that I go to this much trouble to validate all of your pet peeves too, but sometimes it isn’t possible.

My only small vindication is that there are sentences where it is confusing to use while to mean “although,” and then it isn’t allowed. For example, if you said, “While Squiggly is yellow, Aardvark is blue,” people wouldn’t know whether you were contrasting their colors or saying that Aardvark is only blue when Squiggly is yellow. In cases like that, you have to use although.

So, moving forward, I will continue to reserve while for times when I mean “at the same time”—old habits are hard to break—but I will now refrain from striking out while every chance I get. I wonder if the Modern Manners Guy will want me to send apology cards to all the writers I terrorized about this over the years. I hope not!

Next, I have two related bonus facts for you.

First, there isn’t any difference between although and though when they are being used as described above. Though is a less formal version of although, but it’s in such common use that it’s OK to use it in formal writing too.

Second, while and whilst both mean the same thing. Although whilst is still used in British English, it is considered archaic in American English. It’s just a language quirk that whilst survived in Britain but perished in America.

I ASSURE YOU I WILL ENSURE EVERYONE

HAS INSURANCE: ASSURE VERSUS ENSURE

VERSUS INSURE

Assure, ensure, and insure have the same underlying meaning, but they each have a slightly different use.

Assure is the only one of the three words that means “to reassure someone or to promise.”

I assure you that the chocolate is fresh.

Ensure chiefly means “to make certain or to guarantee.”

He must ensure that the effect is eye-popping.

Insure can be interchangeable with ensure in some cases, but it is easiest to keep these words straight by reserving insure for references to insurance.

I need to insure my car.

The definitions are different in British English: in Britain, assure can mean “to insure against a loss.”

ABANDON YOUR BACKWARD WAYS:

BACKWARD VERSUS BACKWARDS

When backward and backwards are used to describe verbs, both words are correct and interchangeable.

The children moved backward/backwards.

Count backward/backwards from ten to one.

The s is more common in Britain than in the United States, so you should consider what the convention is in your country and use backwards in Britain and backward in the United States. This regional difference is one reason you’re probably confused. If you read The New York Times and BBC websites in the same day, you could see the word used both ways.

The exception is that you never use the s when you use backward as an adjective (in other words, to describe a noun). It is always backward as an adjective.

They couldn’t understand the peeves’ backward ways.

Aardvark wondered if the program had backward compatibility.

So if you are in the United States, you have it easier because you can just remember that it’s always backward, without the s, not backwards. We like shortcuts here, like drive-through restaurants, so you can remember that we’ve lopped off the s. But, if you are using British English, then you have to remember that it’s backwards as an adverb and backward as an adjective.

The story is similar for the words toward and towards: both are correct and interchangeable, and you can use either one because they mean the same thing. The s is more common in Britain than in the United States, so you should take into account what the convention is in your country and use towards in Britain and toward in the United States. Again, a memory trick can be to remember that Americans like shortcuts.

I FEEL BAD: BAD VERSUS BADLY

Interviewers often ask if people are afraid to write to me, and the answer, sadly, is yes. I get a lot of e-mail messages in which people (even my mother!) include blanket requests for forgiveness for any unidentified grammar errors. I feel bad about that—my goal isn’t to make people self-conscious or afraid.

In addition, I get skewered when I make an error (or perceived error) myself. So when I was quoted in an article saying, “I feel bad about that,” a lot of readers saw a chance to send me a gotcha e-mail message about using bad to modify feel. They maintained that I should have said, “I feel badly about that.” I’m not perfect, and I make lots of errors (especially in live interviews), but this isn’t one of them.

The quick and dirty tip is that it is correct to say you feel bad when you are expressing an emotion. To say “I feel badly” could imply that there’s something wrong with your sense of touch. Every time I hear people say, “I feel badly,” I imagine them in a dark room having trouble feeling their way around with numb fingers.

I get that image because badly is an adverb, meaning that it modifies a verb (adverbs sometimes modify adjectives and other adverbs too). So when you say, “I feel badly,” the adverb badly relates to the action verb feel. Since the action verb feel can mean “to touch things,” feeling badly can mean you’re having trouble touching things.

This is a problem with most of the verbs that describe senses such as taste and smell. Consider the different meanings of these two sentences:

I smell bad.

I smell badly.

When you say, “I smell badly,” badly is an adverb that modifies the verb smell. You’re saying your sniffer isn’t working, just as when you say you feel badly you’re saying your fingers aren’t working. When you say, “I smell bad,” bad is an adjective, which means it modifies a noun. You’re saying you stink, just as when you say, “I feel bad,” you’re saying you are regretful or sad or ill or wicked.

The reason people often think they should say they feel badly is that it’s only after linking verbs such as feel, smell, and am that you use an adjective such as bad. With most other verbs, it’s correct to use the adverb. For example, if you gave a horrible speech, you could say, “It went badly.” If a child threw a fit in a shopping mall, it would be correct to say, “She behaved badly.” The quick and dirty tip is to remember the following:

Adjectives follow linking verbs.

Adverbs modify action verbs.

See here and here for further discussion about linking verbs.

CHOOSE BETWEEN THE BEES AND THE TWEENS: BETWEEN VERSUS AMONG

There is a difference between between and among: you use between when you are writing about two things and among when you are writing about more than two things. That’s a quick and dirty tip, and there are exceptions, but if you remember that between is for two things and among is for more than two things, then you’ll be right most of the time.

I’m expecting to hear a collective groan about the corny mnemonic that I’m going to give you, but I do think it will help you remember when to use the word between. Here’s the sentence: Squiggly dreaded choosing between the bees and the tweens. The idea is that Squiggly is choosing between two different groups—bees and tweens—and the correct word is between.

Here’s a bonus: the difference between among and amongst is similar to the difference between while and whilst. Amongst is more common in British English and is considered old-fashioned or archaic in American English.

The Inbetweeners

For those of you who may not know, tween is a word that’s used to describe kids who are at that weird stage between childhood and their teenage years. Depending on whom you ask, a tween can be a youth who is anywhere from eight to fourteen years old.

I know some of you will be wondering about the exception to that rule. Here’s the deal: you can use the word between when you are talking about distinct, individual items even if there are more than two of them. For example, you would say, “She chose between Harvard, Brown, and Yale,” because the colleges are individual items she is choosing between. On the other hand, if you were talking about the colleges collectively you would say, “She chose among the Ivy League schools.”

BRING IT ON: BRING VERSUS TAKE

I received a comment about bring versus take that I found especially interesting from a man named Farrel, who is from an unspecified country. His impression is that everyone in his home country knows the difference between bring and take, and it’s just Americans who don’t seem to be able to get it right. I don’t know if that’s true, but I’ll take his word for it and try to do my part to fix the problem.

Whether you use bring or take depends on your point of reference for the action. The quick and dirty tip is that you ask people to bring things to the place you are, and you take things to the place you are going. For example, I would ask Aardvark to bring Squiggly to my party next week, and then Aardvark would call Squiggly and ask, “May I take you to Grammar Girl’s party?”

I am asking Aardvark to bring Squiggly because I am at the destination—from my perspective, Aardvark is bringing someone here. Aardvark is offering to take Squiggly because he is transporting Squiggly to a remote destination—from Aardvark’s perspective, he is taking someone there.

Here are two examples that help me remember.

First, think of a restaurant where you order food to go. It’s often informally called getting “takeout.” When you get take-out food, you’re moving the food from your location (the restaurant) to somewhere else (a destination). And it’s take-out food, not bring-out food. You’re taking the food to a destination.

Second, if I’m sitting at home feeling lazy, wishing dinner would appear, I would say, “I wish someone would bring me dinner.” I imagine Pat stopping at a restaurant and getting dinner to go. From my perspective, he is bringing me dinner because dinner is coming to my location.

I suspect that one reason people get confused about bring and take is that there are many exceptions to the basic rules. For example, idioms such as bring home the bacon and take a bath and phrasal verbs such as bring up, bring about, take down, and take after don’t comply with the rule that bring means to cause something to go to the speaker and take means to cause something to go away from the speaker.

Nevertheless, when your point is that something is being moved from one location to another, the rule is that things are brought to the speaker and taken away from the speaker. You ask people to bring things to you, and you take things to other people. You ask people to bring you coffee, and you offer to take the dishes to the kitchen. You tell people to bring you good news, and you take your camera to the beach.

As an aside, the past tense of bring is brought, as in He brought me dinner. In some regions people say brung or brang, but those words aren’t standard English.

Finally, an interesting note is that the words come and go follow rules that are similar to those for bring and take. Come is like bring: you ask people to come here—to come to where you are. And go is like take: you tell people to go away—to move away from your location. Aardvark and Squiggly will come to my party, and when Aardvark calls Squiggly, he’ll say, “Let’s go to Grammar Girl’s party.”

IF YOU MUST USE BAD GRAMMAR,

DON’T DO IT BY ACCIDENT: BY ACCIDENT

VERSUS ON ACCIDENT

Some of the most difficult questions I get are from people who didn’t grow up speaking English and who want to know why we use a particular preposition in a specific phrase. Why do we say I’m in bed instead of I’m on bed? Do people suffer from a disease or suffer with a disease? Are we in a restaurant or at a restaurant? I’m a native English speaker, so my first thought is usually something like, “I don’t know why; in bed just sounds right,” and sometimes either option seems correct.

But there’s one question I am able to answer—Why do some people say “on accident” and some people say “by accident”?—because I was lucky enough to find an entire research paper on the topic, published by Leslie Barratt, a professor of linguistics at Indiana State University.*

According to Barratt’s study, use of the two different versions appears to be distributed by age. Whereas on accident is common in people under thirty-five, almost no one over forty says on accident. Most older people say by accident. It’s quite amazing: the study says that on is more prevalent under age ten, both on and by are common between the ages of ten and thirty-five, and by is overwhelmingly preferred by those over thirty-five. (I’m over thirty-five, and I definitely prefer by accident.)

An interesting conclusion from the paper is that although there are some hypotheses, nobody really knows why younger people all over the United States started saying on accident instead of by accident. For example, there’s the idea that on accident is parallel to on purpose, but nobody has proven that children all across the country started speaking differently from their parents because they were seeking parallelism. Although I have no proof, I suspect that it must have something to do with nationwide media since it is such a widespread age-related phenomenon. Barney & Friends hasn’t been on TV long enough to be the culprit, and Sesame Street has been on TV too long to be the culprit. Really, all we can say is that it’s just one of those language things that happens sometimes.

Although on accident grates on the ears of many adults, Barratt found that there is no widespread stigma associated with saying on accident. So it seems to me that as the kids who say on accident grow up (some of whom are even unaware that by accident is an option, let alone the preferred phrase of grown-ups), on accident will become the main, accepted phrase. By that time, there won’t be enough of us left who say by accident to correct them!

THE CAN-CAN DANCE: CAN VERSUS MAY

Legions of exasperated teachers have responded, “May I go to the bathroom!” when children raise their hands and ask, “Can I go to the bathroom?” Technically, can is used to ask if something is possible, and may is used to ask if something is permissible. So yes, those kids can go to the bathroom (we hope!); what they need is to know if they have their teachers’ permission to proceed—if they may go to the bathroom. Nevertheless, substituting can for may is done so commonly it can hardly be considered wrong. This is what I call a cover letter grammar topic—use may when you are in formal situations or want to be especially proper, but don’t get too hung up about it in everyday life.

A CAPITOL IDEA: CAPITAL VERSUS CAPITOL

When the noun capitol ends with an -ol, it is referring to state capitol buildings or the Capitol building in Washington, D.C. You can remember that the rotunda of the Capitol building is round like the letter o.

The other kind of capital, with an -al at the end, refers to uppercase letters, wealth, or a city that is the seat of government for its region or is important in some way. Don’t get confused by the fact that capital with an -al is used for a capital city and capitol with an -ol is used for a state’s capitol building. Just remember that capitol with an -ol refers only to buildings, and fix in your mind that image of the round, o-like rotunda of the U.S. Capitol building. (See the rules about capitalizing capitol.)

I LIKE TO GIVE COMPLIMENTS:

COMPLIMENT VERSUS COMPLEMENT

Imagine the voice of a movie trailer announcer: “Two words. One pronunciation. In a world where choosing the right word can mean life or death, Squiggly must make a decision: i or e.”

OK. You can stop imagining the corny voice now. Fortunately for Squiggly, I have a great memory trick for remembering the difference between compliment and complement. A compliment (with an i) is a word of praise, so just remember the sentence

I like to give compliments.

Complement (with an e) means that something pairs well with something else. You can remember the meaning by thinking things that complement each other often complete each other, and complement and complete both have e’s in them.

Things that complement each other often complete each other.

IT’S DECEPTIVELY INFLAMMABLE:

WORDS THAT SHOULD BE BANNED

If you write that a crossword puzzle is deceptively easy, does that mean it is easy or hard? The answer is that using the word deceptively can lead to confusion, and the best approach is to rewrite the sentence.

There’s a similar story for the word inflammable. Some people think it means “easy to burn” and other people think it means “resistant to burning.” It’s best to avoid it altogether.

PEOPLE FEAR THINGS THAT ARE DIFFERENT:

DIFFERENT FROM VERSUS DIFFERENT THAN

Different from is preferred to different than. I remember this by remembering that different has two f’s and only one t, so the best choice between than and from is the one that starts with an f.

Squiggly knew he was different from the other snails.

IN OTHER WORDS, GET IT RIGHT:

I.E. VERSUS E.G.

Misusing i.e. and e.g. is one of the top five mistakes I used to see when editing technical documents. People are so mixed up (and so certain in their confusion) that I would get back drafts from clients where they had actually crossed out the right abbreviation and replaced it with the wrong one. I had to just laugh.

I.e. and e.g. are both abbreviations for Latin terms. I.e. stands for id est and means “that is.” E.g. stands for exempli gratia, which means roughly “for example.” “Great. Latin,” you’re probably thinking. “How am I supposed to remember that?”

But by now, I’m sure you know that I’m not going to ask you to remember Latin. I’m going to give you a memory trick! So here’s how I remember the difference. Forget about i.e. standing for “that is.” From now on, to you, i.e., which starts with i, means “in other words,” and e.g., which starts with e, means “for example.”

Starts with i = in other words

Starts with e = example

A few listeners have also written in to say they remember the difference between i.e. and e.g. by imagining that i.e. means “in essence,” and noting that e.g. sounds like “egg,” as in “egg-sample,” and those are good memory tricks too.

So now that you have a few tricks for remembering what the abbreviations mean, let’s think about how to use them in a sentence.

E.g. means “for example,” so you use it to introduce an example:

Aardvark likes card games, e.g., bridge and crazy eights.

Squiggly visited Ivy League colleges, e.g., Harvard and Yale.

Because I used e.g., you know I have provided a list of examples of card games that Aardvark likes and colleges Squiggly visited. It’s not a definitive list of all card games Aardvark likes or colleges Squiggly visited; it’s just a few examples.

On the other hand, i.e. means “in other words,” so you use it to introduce a further clarification:

Aardvark likes to play cards, i.e., bridge and crazy eights.

Squiggly visited Ivy League colleges, i.e., Harvard and Yale.

Because I used i.e., which introduces a clarification, you know that these are the only two card games Aardvark enjoys and the only two colleges Squiggly visited.

Here are two more examples:

Squiggly loves watching old cartoons (e.g., DuckTales and Tugboat Mickey). The words following e.g. are examples, so you know that they are just some of the old cartoons Squiggly enjoys.

Squiggly loves watching Donald Duck’s nephews (i.e., Huey, Dewey, and Louie). The words following i.e. provide clarification: they tell you the names of Donald Duck’s three nephews.

An important point is that if I’ve failed, and you’re still confused about when to use each abbreviation, you can always just write out the words “for example” or “in other words.” There’s no rule that says you have to use the abbreviations.

Here are a few other things about i.e. and e.g. Don’t italicize them; even though they are abbreviations for Latin words, they’ve been used for so long that they’re considered a standard part of the English language. (I.e. and e.g. are italicized in this section because I use italics to highlight words that are being discussed as words instead of being used for their meaning.) Also, remember that they are abbreviations, and there is always a period after each letter.

Also, I always put a comma after i.e. and e.g. I’ve noticed that my spell checker always freaks out and wants me to remove the comma, but five out of six style guides recommend using the comma.

Finally, I tend to reserve i.e. and e.g. to introduce parenthetical statements, but it’s also perfectly fine to use i.e. and e.g. in other ways. You can put a comma before them, or if you use them to introduce a main clause that follows another main clause, you can put a semicolon before them. You can even put an em dash before i.e. and e.g. if you are using them to introduce something dramatic. They’re just abbreviations for words, so you can use them in any way you’d use the words in essence or for example.

I WANT EACH OF YOU TO WIN:

EACH VERSUS EVERY

Each and every mean the same thing and are considered singular nouns, so they take singular verbs. (Note the singular verbs in the following examples.) If you want to get technical, you can use each to emphasize the individual items or people:

Each car is handled with care.

and every to emphasize the larger group:

Every car should use hybrid technology.

People often say “each and every” for emphasis, but it is redundant.

EVERYONE LOVES SQUIGGLY:

EVERYONE VERSUS EVERYBODY

Everyone and everybody mean the same thing: every person. You can use them interchangeably and they are considered singular.

Everyone loves Squiggly.

Everybody is coming over after the parade.

FARTHER THAN YOU’VE EVER GONE BEFORE:

FURTHER VERSUS FARTHER

The quick and dirty tip here is that you use farther to talk about physical distance and further to talk about metaphorical or figurative distance. It’s easy to remember because farther has the word far in it, and far obviously relates to physical distance.

For example, you might say, “Squiggly and Aardvark walked to a town far, far away. After many miles, Squiggly grew tired. ’How much farther?’ he asked in despair.”

Did you see that? Squiggly used farther because he was asking about physical distance.

If Aardvark were frustrated with Squiggly, he might say, “Squiggly, I’m tired of your complaining; further, I’m tired of carrying your maracas.” In this case, Aardvark used further because he isn’t talking about physical distance, he’s talking about metaphorical distance: further along the list of irritations.

Sometimes the quick and dirty tip breaks down because it’s hard to decide whether you’re talking about physical distance or not. For example, take a look at this sentence: I’m further along in my book than you are in yours. You could think of it as a physical distance through the pages and use farther or as a figurative distance through the story and use further.

The good news is that in these ambiguous cases it doesn’t matter which word you choose. It’s fine to use further and farther interchangeably when the distinction isn’t clear. People have been using them interchangeably for hundreds of years!

Just remember that farther has a tie to physical distance and can’t be used to mean “moreover” or “in addition.” When I mean “in addition,” I always use furthermore instead of further. Because furthermore and farther are more different from each other than further and farther, I never get confused.

Aardvark’s feet hurt. Furthermore, Squiggly’s complaining was driving him batty.

He reminded Squiggly they didn’t have much farther to go.

An interesting side note is that in Britain people use the word farther much less than people do in the United States. At least one source speculates that this is because with British pronunciation, farther sounds too much like father.

I AM WOMAN, HEAR ME ROAR:

FEMALE VERSUS WOMAN

Regardless of your political beliefs, I believe everyone can agree that this has been an amazing year for women in politics. First, Nancy Pelosi became the first female Speaker of the House, and then Hillary Clinton became the first woman to have a good chance of becoming president of the United States.

Because of these events, writers have spilled a lot of ink on stories about female advances, which means I have received a lot of messages asking about correct use of female and woman.

Before I answer the usage question, I want to address a related issue, which is that some people may argue that it’s sexist to point out these women’s sex. They say that such language implies that it’s unexpected that the Speaker would be a woman, in the way that saying someone is a male nurse or a female doctor wrongly implies that men aren’t usually nurses or that women aren’t usually doctors. But, given that Nancy Pelosi is, for example, actually the first woman to ever be Speaker of the House, I don’t believe it’s sexist to point out that she is a woman because that fact is an exciting and unique part of the story.

So then, what is the best way to talk about Nancy Pelosi being a woman? The word woman is primarily a noun, but it is also less commonly used as an adjective (which means in some cases it can be used to modify nouns).

A quick and dirty tip for testing the validity of using woman as an adjective in a particular sentence is to substitute the word man to see if it makes sense. For example, it sounds ridiculous to say someone is “the first man Speaker of the House.” Of course, you would say “male Speaker of the House.” So, even though it’s not strictly wrong to use woman as an adjective, it’s better to use the primary adjective, female, and say that Nancy Pelosi is the first female Speaker of the House.

IF THERE WERE FEWER GRAMMARIANS . . . :

LESS VERSUS FEWER

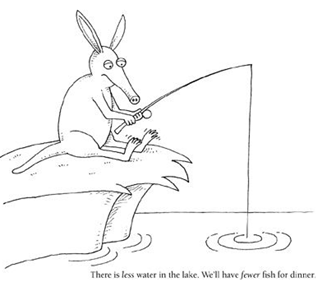

Less and fewer are easy to mix up. They mean the same thing—the opposite of more—but you use them in different circumstances. The quick and dirty tip is that you use less with mass nouns and fewer with count nouns.

Count Nouns Versus Mass Nouns

I’m worried that I’ve scared you off, but it’s easy to remember the difference between mass nouns and count nouns.

A count noun is just something you can count. I’m looking at my desk and I see books, pens, and M&M’s. I can count all those things, so they are count nouns and the right word to use is fewer. I should eat fewer M&M’s.

Mass nouns are just things that you can’t count individually. Again, on my desk I see tape and clutter. Those things can’t be counted individually, so the right word to use is less. If I had less clutter, my desk would be cleaner. Another clue is that you don’t make mass nouns plural: I would never say I have clutters on my desk or that I need more tapes to hold my book covers together.

Sometimes it isn’t obvious if something is a mass noun or a count noun because some words can be used in different ways. For example, coffee can refer to either a mass of liquid or a cup of liquid. If you’re responsible for filling the coffee decanter at a wedding, and you’re getting carried away, your boss may ask you to make less coffee. But if you’re a waiter serving cups of coffee to the tables, and the crowd is waning, your boss may tell you to take out fewer coffees next time. She means cups of coffee, but it’s common to hear that shortened to just coffee as in Bring me a coffee, please. Remember that I said mass nouns (such as coffee) can’t be made plural? In this example, I’ve made a mass noun plural (coffees), but in the process I transformed it into a count noun. So the rule still holds.

Furniture is another tricky word; it isn’t immediately obvious whether it is a mass noun or a count noun. If I think of a furniture store, I think of lots of individual pieces of furniture, but furniture is a collective name for a mass of stuff. You could say, “Look at all those chairs,” but you would never say, “Look at all those furnitures.” Furniture is a mass noun, and chair is a count noun. Therefore, you’d say, “We need less furniture in this dance hall. Can we have fewer chairs?”

Exceptions

There are exceptions to these rules; for example, even though we count hours, dollars, and miles, it is customary to use the word less to describe time, money, and distance (perhaps because these things can be divided into infinitely small units). For example, you could say, “That wedding reception lasted less than two hours. I hope they paid the band less than four hundred dollars.” So keep in mind that time, money, and distance are different, but if you stick with the quick and dirty tip that less is for mass nouns and fewer is for count nouns, you’ll be right most of the time.

Memory Tricks

There are two ways I remember when to use less and when to use fewer.

First, I think of the classic example of the grocery store express lane. Most of the signs for these lanes read, “10 items or less,” and that’s just wrong. The signs should read, “10 items or fewer,” because items are individual, countable things. Between hearing people complain about the signs and seeing the signs every week or so, it sticks in my head that it should be fewer items. And when I stand in line and count the fifteen items that belong to the person in front of me in the ten-items-or-fewer lane, I’m strongly reinforcing the idea that items are countable.

Second, I have a memory trick, and I’ve even had a cartoon drawn up so that you can see into my imagination. I think of Aardvark sitting by a lake. He’s fishing. The water is low in the lake this year, so there is less water in the lake. You can’t count water in a lake. Less and lake both begin with the letter l. There is less water in the lake. Squiggly is worried about dinner. Aardvark usually catches four fish, but what if there are only three? “We’ll have fewer fish for dinner,” Squiggly thinks to himself fretfully. You can count fish. Fewer and fish both start with the letter f, and Squiggly is counting fish in his head. They’ll have fewer fish for dinner.

HOW YOU DOIN’?: GOOD VERSUS WELL

It’s such a simple little question: how are you? But I’ve heard from people who feel a twinge of trepidation or even full-blown frustration every time they have to decide whether to say they’re good or they’re well.

“I’m good,” is what you’re likely to hear in general conversation, but there are grammar nitpickers out there who will chide you if you say it. The wonderful news is that those nitpickers are wrong: it’s perfectly acceptable to say, “I’m good,” and you shouldn’t have to shamefully submit to teasing remarks such as the time-honored and leering, “How good are you?”

The nitpickers will tell you that well is an adverb (and therefore modifies verbs) and that good is an adjective (and therefore modifies nouns), but the situation isn’t that simple.

The key is to understand how linking verbs differ from action verbs. (Trust me, this is worth it so you can look people in the eye and say, “I’m good,” with absolute confidence.)

First, let’s talk about action verbs. They’re easy; they describe actions. Verbs such as run, jump, and swim are all action verbs. If you want to describe an action verb, you use an adverb such as well. You could say, “He runs well; she jumps well; they swim well.” Well is an adverb that relates to all of those action verbs.

Linking verbs, on the other hand, are a bit more complicated. Linking verbs aren’t about actions as much as they are about connecting other words together. They’re also sometimes called “copulative verbs.”

I think of the verb to be as the quintessential linking verb. The word is is a form of the verb to be, and if I say, “Squiggly is yellow,” the main purpose of is is really just to link the word Squiggly with the word yellow. Other linking verbs include seem, appear, look, become, and verbs that describe senses, such as feel and smell. That isn’t a comprehensive list of linking verbs—there are at least sixty in the English language—but I hope I’ve given you an idea of how they work. (See the appendix for a list of common linking verbs.)

One complication is that some verbs—such as the sensing verbs—can be both linking verbs and action verbs. A trick that will help you figure out if you’re dealing with a linking verb is to see if you can replace the verb with a form of to be; if so, then it’s probably a linking verb.

For example, you can deduce that feels is a linking verb in the sentence He feels bad because if you replace feels with the word is, the sentence still makes sense:

He feels bad.

He is bad.

(The sentence makes sense; feels was a linking verb)

On the other hand, you can deduce that feels is an action verb in the sentence He feels badly because if you replace feels with is, the sentence doesn’t make sense anymore:

He feels badly.

He is badly.

(The sentence doesn’t make sense; feels was an action verb)

OK, so now you understand the difference between linking verbs and action verbs. That may seem like a detour on the way to learning why it is OK to say, “I’m good,” but it’s important because the thing people seem to forget is that it’s standard to use adjectives—such as good—after linking verbs. When you do it, they are called predicate adjectives, and they refer back to the noun before the linking verb. That’s why, even though good is primarily an adjective, it is OK to say, “I am good”: am is a linking verb, and you use adjectives after linking verbs.

Aside from the linking-verb-action-verb trickiness, another reason people get confused about this topic is that well can be both an adverb and a predicate adjective. As I said earlier, in the sentence He swam well, well is an adverb that describes how he swam. But when you say, “I am well,” you’re using well as a predicate adjective. That’s fine, but most sources say well is reserved to mean “healthy” when it’s used in this way. So if you are recovering from a long illness and someone is inquiring about your health, it’s appropriate to say, “I am well,” but if you’re just describing yourself on a generally good day and nobody’s asking specifically about your health, a more appropriate response is, “I am good.”

Finally, it’s very important to remember that it’s wrong to use good as an adverb after an action verb. For example, it’s wrong to say, “He swam good.” Cringe! The proper sentence is He swam well, because swam is an action verb and it needs an adverb to describe it. Remember, you can only use adjectives such as good and bad after linking verbs; you can’t use them after action verbs.

LET’S GET THOSE KIDS GRADUATED:

GRADUATED VERSUS GRADUATED FROM

Every graduation season I get e-mail messages complaining about people who say “Johnny graduated high school.” And those complainers are right to be annoyed.

Although the graduated high school construction is becoming more common, it is incorrect. Here are the proper ways to use the verb graduated:

A school does the act of graduating a student: Stanford graduated thousands of students this year.

Students are graduated from a school: Squiggly graduated from Stanford.

If you want to be persnickety, you can also say a student was graduated from a school: Squiggly was graduated from Stanford.

WELL, I’LL BE HANGED: HANGED

VERSUS HUNG

When you’re talking about the past tense, curtains were hung and people were hanged. You can remember that by thinking of “’Twas the night before Christmas”: “The stockings were hung by the chimney with care.” That’s right. Stockings were hung. On the other hand, the standard English word is hanged when you are talking about killing people by dangling them from a rope. Therefore, it’s correct to say that Saddam Hussein was hanged in Baghdad. To remember hanged, I think of a prospector in the Old West expressing surprise by saying, “I’ll be hanged!” Hangings were common in the Old West.

It seemed a little curious to me that there would be two past-tense forms of the word hang that differ depending on their meaning, so I did a little digging and found out that in Old English there were two different words for hang (hon and hangen), and the entanglement of these words (plus an Old Norse word hengjan) is responsible for there being two past-tense forms of the word hang today.

IMPACT

Impact has taken root in the business world as a replacement for affect, as in Cutting prices will impact our salespeople. The problem is that many people object to using impact this way; they maintain that it means “to hit” and that any other use is jargon.

Yes, you will find the definition “to influence” in the dictionary under impact, but trust me, you’ll lead a happier life if you shun such usage.

IF I WANTED TO WAIT ONLINE, I’D BE AT MY

COMPUTER: IN LINE VERSUS ON LINE

A common regionalism that listeners ask me about is people using the phrase on line instead of in line to mean they are physically waiting in a row with other people. For example, Mary wrote that she read a story in The New York Times describing people standing on line instead of standing in line. She said she’s been hearing it more and more in the past few years and thinks it sounds ridiculous, and a listener named Julie noted that it’s irritating because when people say they are on line, she assumes they are on the Internet.

There’s nothing grammatically incorrect about using on line to mean standing in line; it just sounds strange to people who aren’t used to hearing it. An online language map from the University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee shows that people who say on line are clustered in New York City, New Jersey, Connecticut, Massachusetts, possibly Philadelphia. This is a very small but densely populated, media-rich area. The phrase standing on line will probably spread as it becomes widely distributed by New York television programs and publications and as people travel and move in and out of the region.

Today, a Google search for “standing in line” returns about thirty-seven times as many hits as a search for “standing on line,” so it would appear that for the time being in line is still much more common.

INTO THE WILD: INTO VERSUS IN TO

Into is a preposition that has many definitions, but they all generally relate to direction.

On the other hand, in by itself can be an adverb, preposition, or adjective (and to by itself is a preposition or an adverb). Sometimes in and to just end up next to each other.

Maybe examples will help!

He walked into the room.

(Which direction was he going? Into the room.)

We broke in to the room.

(“Broke in” is a phrasal verb. What did you break in to? The room.)

SPITEFUL GRAMMAR: IN SPITE OF VERSUS

DESPITE

“In spite of” and “despite” mean the same thing and are interchangeable. For example, it is correct to say either of the following:

She ran well despite having old shoes.

She ran well in spite of having old shoes.

Some people prefer “despite” because it is shorter. (“In despite of” is wrong.)

IT’S HORRIBLE: IT’S VERSUS ITS

When I was in second grade, I lost a spelling bee because I misspelled the word its. I put an apostrophe in when I shouldn’t have, and it was a very traumatic moment in my young life. I think this lesson is burned into my mind precisely because of my past misdeeds, and although I can’t change my past, I believe the next best thing would be to save all of you from similar apostrophe-induced horrors.

It’s with an apostrophe s always means “it is” or “it has.” For example, you could write, “It’s lunch time,” with it-apostrophe-s, or you could write, “It is lunch time,” without the contraction. It’s is a contraction of two words: it is.

It’s [it is] lunch time.

It’s [it is] a shame the chocolate tree is out of season.

Its is the possessive form of it. You would use its without the apostrophe in sentences like these:

The tree needs its branches trimmed.

The chocolate tree has a scratch on its trunk.

Every time I see the eBay commercials with three-dimensional “its” standing in for products, I flash back to second grade and feel as if the its are out to get me. So maybe that odd image of wild crazy its chasing Grammar Girl around the room can help you remember to use special care when confronted with its. They’re very dangerous!

The reason for the confusing its-trap is that its without an apostrophe is a possessive pronoun just like hers, ours, and yours. None of the possessive pronouns take an apostrophe s to become possessive. You make most words possessive by adding an apostrophe s to the end, but not pronouns. Who is the other pronoun that can cause apostrophe confusion because it can also exist with or without an apostrophe s. That’s because who’s is a contraction for who is or who has. Whose is the possessive form of who.

Who’s at the door?

Whose door is that?

Just remember to take an extra second to consider whether you are using the right form of its and whose. Even if you know the difference, it’s easy to slip up when you are writing quickly.

WHAT I LIKE ABOUT YOU: LIKE VERSUS AS

I bet you didn’t know there is a raging grammar war about the word like (and I’m, like, not even, like, referring to Valley Girl dialect). If you don’t believe me, walk into a room full of grammarians, plop down in a comfy chair, and say, “It’s like I’m sitting in my own living room.” I dare you!

The background is that traditionally like is a preposition and as is a conjunction. Nevertheless, people have been using like as if it were a conjunction for at least one hundred years, and grammarians have been raging against that use for just as long.

First, let’s quickly review prepositions and conjunctions. Prepositions create relationships between words in a clause or phrase. Examples are in, around, and through. Note that prepositions are not usually followed by verbs.

Squiggly walked through the door.

Aardvark was in the loft.

A conjunction connects words, phrases, or clauses. Common conjunctions are and, but, and or. Note that an entire clause (including a verb) can follow a conjunction.

Squiggly walked through the door and caught

Aardvark in the loft.

The proper way to differentiate between like and as is to use like when no verb follows.

Squiggly throws like a raccoon.

It acted just like my computer.

Notice that when I use like, the words that come after are generally simple. A raccoon and my computer are the objects of the preposition.

If the clause that comes next includes a verb, then you should use as.

Squiggly throws as if he were a raccoon.

He acted just as I would expect him to behave.

Notice that when I use as, the words that come after tend to be more complex.

You generally hear like used in everyday speech, so that helps me remember that like is the simpler word—at least it is followed by simpler words. As sounds stuffier and is followed by a more complex clause that contains a verb.

Whether you abide by this rule or not probably depends on how much of a grammar stickler you are. It’s common to hear sentences like this: It’s like I’m back in high school. And as a result, many people don’t know it’s wrong.

I have to admit that after researching this topic I felt a bit browbeaten. Even as like is becoming more entrenched in everyday use, professional grammarians are absolutely resolved that this is a trend worth fighting against. Many language experts seem fully prepared to rail against the conjunctive use of like with all their might.

So my advice is don’t do it—don’t use like as a conjunction, especially in writing, unless you are ready for the full force of rampaging grammarians to rain down on you (which is not what I’m generally going for in the advice I give you).

Here are more examples of correct sentences to help you remember the rule:

My cousin looks like Batman.

My neighbor yelled like a maniac.

It’s as if my cousin were Batman.

My neighbor yelled as though he were a maniac.

A final note is that there is no discernible difference between as if and as though. Some sources say that as if is often used for less likely scenarios—my cousin being Batman—and as though for more likely scenarios—my neighbor is a maniac—but this isn’t a definitive rule.

PLEASE, TAKE THIS LITERALLY: LITERALLY

The word literally literally means “in a literal sense.” Exactly. Without exaggeration. Word for word. When you say your head is going to literally explode, there are a lot of people whose blood pressure literally rises as they imagine putting lit firecrackers in your ears to make your sentence correct. It’s best to avoid using literally to add extra emphasis to your writing.

Squiggly’s head is about to literally explode.

I WISH I MAY, I WISH I MIGHT:

MAY VERSUS MIGHT

The difference between may and might is subtle. If something is likely to happen, use may:

Squiggly may come over later.

Aardvark may get dressed up.

If something is a mighty stretch, use might:

Squiggly might win the lottery.

Aardvark might grow wings and fly.

THE PET PEEVE OF HARD-CORE NITPICKERS:

NAUSEOUS VERSUS NAUSEATED

Many people say they are nauseous when their stomach is queasy. Using nauseous in that way sometimes makes sticklers nauseated because they stick with the rule that nauseous means to induce nausea, whereas nauseated means you feel sick.

The nauseous fumes permeated the room.

The fumes were nauseating.

We all felt nauseated.

So although only the most irritating people will judge you on your grammar when you’re describing how sick you feel, it’s best to avoid nauseous altogether and use nauseated when you’re well enough to care about word choice and nauseating when you’re describing something that makes you sick.

I’M PASSING OUT MEMORY TRICKS:

PASSED VERSUS PAST

Past is a noun you use when talking about a long time ago: that was in the past.

Passed is a verb you use when talking about going by something: we passed the store a mile ago.

My quick and dirty tip for remembering the difference is to make an “ssss” sound when you pass by things (whossshhh) to help you remember that the word with two s’s is an action. Sure it’s silly, and the other people in your car may look at you strangely, but I bet you’ll remember, and wouldn’t you rather have people question your sanity than your grasp of the English language?

GUILTY AS CHARGED: PLED VERSUS PLEADED

Can you open a newspaper these days without reading about a star or politician pleading guilty to a crime? I’d guess not, given how many e-mail messages I receive asking about the correct use of the verb to plead!

Although pled and pleaded are both in common use, language sticklers prefer pleaded.

Squiggly pleaded guilty to stealing the chocolate tree seeds.

Sir Fragalot pleaded guilty to shouting incomplete sentences in the town square.

A Google News search returns about six hundred entries for “pled guilty” and about thirty-seven thousand entries for “pleaded guilty.”

PEOPLE THESE DAYS: PEOPLE VERSUS PERSONS

Nowadays, people is almost always the right choice when you are talking about more than one person.

How many people were at the party?

Eight people showed up.

Some dictionaries don’t even include persons as the plural of person anymore, and most of the dictionaries that do include persons note that it is uncommon, archaic, or going out of style. Traditionally, people was proper when referring to a mass of people (e.g., Squiggly couldn’t believe how many people were at the fair), and persons was proper when referring to a distinct number of individuals (e.g., Squiggly noted that eight persons showed up for the meeting).

AND THEN THERE WERE NONE: THEN VERSUS THAN

Do you get confused about then versus than? Don’t worry; you aren’t alone. People ask me about this a lot.

Then has an element of time. For example, it can mean “next” or “at that time”:

We ate, and then we went to the movies.

Movies were a lot cheaper back then.

Than conveys a comparison:

DVDs are more expensive than video cassettes.

Aardvark is taller than Squiggly.

The quick and dirty tip is that than and comparison both have the letter a in them, and then and time both have the letter e in them.

WHICH’S BREW: THAT VERSUS WHICH

That versus which is covered so frequently in grammar books that I almost hate to bring it up, but using the wrong word is such a common mistake that I feel obligated to cover it. I used to edit documents all the time where people used the wrong word, and what really killed me was when I sent a document to a client for review and got it back with a perfectly fine that changed to a which.

Here’s the deal: some people will argue that the rules are more complex and flexible than this, but I like to make things as simple as possible, so I say that you use that before a restrictive clause and which before everything else.

A restrictive element is just part of a sentence you can’t get rid of because it specifically restricts the noun. Here’s an example:

Gems that sparkle often elicit forgiveness.

The words that sparkle restrict the kind of gems you’re talking about. Without them, the meaning of the sentence would change. Without them, you would be saying that all gems elicit forgiveness, not just the gems that sparkle. (Note also that you don’t need commas around the words that sparkle.)

A nonrestrictive element is something that can be left off without changing the meaning of the sentence. You can think of a nonrestrictive element as simply additional information. Here’s an example:

Diamonds, which are expensive, often elicit forgiveness.

Alas, in Grammar Girl’s world, diamonds are always expensive, so leaving out the words which are expensive doesn’t change the meaning of the sentence. Also note that the phrase is surrounded by commas.

A quick and dirty tip (with apologies to Wiccans and Hermione Granger) is to remember that you can always throw out the “whiches” and no harm will be done. If it would change the meaning to throw out the element, then you need a that. For example, do all cars use hybrid technology? Is every leaf green? The answer is no: only some cars have hybrid technology and only some leaves are green. It would change the meaning to throw out the element in the examples below, so you need a that. Note also the “that element” isn’t surrounded by commas.

Cars that have hybrid technology get great gas mileage.

Leaves that are green contain chlorophyll.

WHO SAYS GRAMMAR IS EASY?: THAT VERSUS WHO

The quick and dirty tip is that you use who when you are talking about a person and that when you are talking about an object. Stick with that rule and you’ll be safe.

But, of course, it is also more complicated than that. The who-goes-with-people rule is the conventional wisdom; on the other hand, there is a long history of writers using that as a relative pronoun when writing about people. Chaucer did it, for example.

So, it’s more of a gray area than some people think, and if you have strong feelings about it, you could make an argument for using that when you’re talking about people. But my guess is that most people who use who and that interchangeably do it because they don’t know the difference. I don’t consider myself a grammar snob—this is quick and dirty grammar, after all—but in this case, I have to take the side of the people who prefer the strict rule. To me, using that when you are talking about a person makes them seem less than human. I always think of my friend who would only refer to his new stepmother as “the woman that married my father.” He was clearly trying to indicate his animosity and you wouldn’t want to do that accidentally.

Finally, even if you accept the conventional wisdom, there are some gray areas and strange exceptions. For example, what do you do when you are talking about something animate that isn’t human? It can actually go either way. I would never refer to my dog as anything less than who, but my fish could probably be a that.

One strange exception is that you can use whose, which is the possessive form of who, to refer to both people and things because English doesn’t have a possessive form of that. So it’s fine to say, “The desk whose top is cluttered with grammar books,” even though it is obviously ridiculous to say, “The desk who is made of cherry wood.”

So now you understand the details, but you can also remember the quick and dirty rule that who goes with people and that goes with things.

THERE IS FIREFIGHTERS ON THE SCENE: THERE IS VERSUS THERE ARE

Newscasters say things such as There is firefighters on the scene with shocking frequency because they turn there is into the contraction there’s. I made this mistake in my own show once early on, so I spent a lot of time pondering what made me do it! Obviously, I would never say, “There is firefighters on the scene,” but somehow that contraction—there’s—just rolls off the tongue in a way that there are doesn’t because of the double r sound. Just know that it’s a language land mine to watch out for, especially when you are speaking instead of writing.

JUST TRY TO STOP ME FROM GETTING ANNOYED: TRY AND VERSUS TRY TO

I got really frustrated while researching the difference between try and and try to because try and is obviously wrong but none of my books seemed willing to take a stand. They all said try and is an accepted informal idiom that means “try to.” They say to avoid try and in formal writing, but not to get too worked up about it otherwise. But none of them addressed what bothers me about the phrase try and, which is that if you use and, as in this example—I’m going to try and visit Aardvark—you are separating trying and visiting. You’re describing two things: trying and visiting. When you use try to—I am going to try to visit Aardvark—you are using the preposition to to link the trying to the visiting.

I may have to put this on my list of pet peeves, and as I’ve said before, people almost always form pet peeves about things that are style issues or where the rules aren’t clear.

YOU’RE MY FAVORITE READER: YOUR VERSUS YOU’RE

I believe people get your and you’re mixed up for a simple reason: the words sound the same. You have to just remember the difference. Your is the possessive form of you.

Do these belong to you?

Are these your maracas?

You’re is a contraction of two words: you are. Remember that an apostrophe can stand in for missing letters, and in this case it stands in for the missing letter a. It doesn’t save much space, but it does change the phrase from two syllables to one syllable, so I guess it serves an honorable purpose.

You are a talented percussionist.

You’re going to be famous someday.

OBJECTIFICATION: SUBJECT VERSUS OBJECT

There are a few word choices that are tricky because before you can choose, you have to determine whether you are talking about the subject or the object of a sentence, so it adds another layer of things you have to remember. Before we get to the word choices in this section, I’m going to explain the difference between a subject and an object. Don’t worry. I know it sounds abstract, but it’s easy.

If we think about people, the subject of the sentence is the person doing something, and the object of the sentence is having something done to them. If I call Squiggly, then I am the subject, and Squiggly is the object. He is the target of my action: calling.

Still having a hard time remembering? Here’s my favorite mnemonic: If I say, “I love you,” you are the object of my affection, and you is also the object of the sentence (because I am loving you, making me the subject and you the object). How’s that? I love you. You are the object of my affection and the object of my sentence. It’s like a Valentine’s Day card and grammar mnemonic all rolled into one.

Lie Down Sally: Lay Versus Lie

If you exclude the meaning “to tell an untruth” and just focus on the setting/reclining meaning of lay and lie, then the important distinction is that lay requires a direct object and lie does not. So, you lie down on the sofa because you are taking an action (and there is no direct object), but you lay the book down on the table because lay refers to the book, which is the target of your action (making the book the direct object).

Those examples are in the present tense, so you are talking about doing something now.

Lie down on the sofa!

Lay down your pencil!

Musical Genius and Memory Tricks

For those of you who are thinking “Direct object? Whatever!” I have a few quick and dirty memory tricks.

You can remember that lie means “to recline,” which is what people do when they lie down. They sound the same: To lie is to “rec-lie-n.” I remember that you use lay when you are laying down an object by thinking of the line “Lay it on me.” You’re laying something (it, the direct object) on me. It’s a catchy, silly, 1970s kind of line, so I can remember it and remember that it is correct.

If you’re into music, you can remember that both the Eric Clapton song “Lay Down Sally” and the Bob Dylan song “Lay Lady Lay” are wrong. They should be “Lie Down Sally” and “Lie Lady Lie.”

To say “Lay down Sally” would imply that someone should grab Sally and lay her down. If Clapton wanted Sally to rest in his arms on her own, the correct line would be “Lie down Sally.” These examples are in the present tense. It’s pretty easy: you lay something down; people lie down by themselves.

But then everything goes haywire because lay is the past tense of lie. It’s a total nightmare! One of my listeners recommended a great memory trick for this one. He uses the rhyme “Yesterday, down I lay” to remember that the past tense of lie is lay.

Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep

One reason I believe that people have a hard time remembering to use lie to mean “recline” is the children’s prayer that includes the line “Now I lay me down to sleep.” The reason the prayer uses lay instead of lie is in that line you are talking about laying yourself down. So you are the object of your own action. Just as you lay a book on the table, you are laying yourself down on the bed.

That kind of sentence construction is unusual, although you will hear it when people talk about doing something to themselves. For example, people do harm to themselves or see themselves in a mirror.

So don’t get confused by that prayer. Just remember that lie means “recline,” if you’ve got a direct object you’ve got to lay it on me, and yesterday, down I lay.

Conjugating Lay and Lie

Lie is an intransitive verb, and lay is a transitive verb.

· Squiggly wanted to lie down.

· Please lay the cat in the mud.

The past tense of lie is lay:

· Last week, Squiggly lay down on the floor.

· The cat lay in the mud after it rained yesterday.

The past participle of lie is lain:

· Squiggly has lain on the floor for days.

· The cat has lain in the mud for hours.

The present participle of lie is lying:

· Squiggly is lying on the floor.

· The cat is lying in the mud.

The past tense of lay is laid:

· Last week, I laid the TPS report on your desk.

· Aardvark forcefully laid the book on the table.

The past participle of lay is laid:

· I have laid the TPS report on your desk.

· Aardvark has forcefully laid the book on the table.

The present participle of lay is laying:

· He is laying the TPS report on your desk as we speak.

· Aardvark considered forcefully laying the book on the table.

Don’t feel bad if you can’t remember these verb forms right away. Practice will help, and truthfully, I still have to look most of them up every time I use them. It’s important to know what you know, and to look up what you don’t know because these are hard-and-fast rules.

Present Tense |

Present Participle |

Past Tense |

Past Participle |

Lay |

Laying |

Laid |

Have laid |

Lie |

Lying |

Lay |

Have lain |

SIT. STAY. ROLLOVER: SIT VERSUS SET

The story with sit and set is similar to the story with lay and lie: set requires a direct object, sit does not. I have a memory trick that may help you remember the difference between the two words. When you’re training a dog, you tell her to sit. My first dog’s name was Dude and she was a girl, so we would tell her, “Sit, Dude. Sit.” And she would plop her little bottom down. She was a good dog. She was a bullmastiff, so actually her bottom wasn’t that little.

So get an image in your mind of a big bullmastiff responding to the command “Sit.” That is how you use sit—for the action of sitting.

Set, on the other hand, requires an object. I would set Dude’s leash on the table, but she would still think we were going for a walk. I know she saw me set it down, but she was always full of hope. In those examples, the leash and the word it were the objects. I set the leash on the table, and she saw me set it down.

So remember that a dog (or person) sits, and you set things, like leashes, down.

Dude, sit!

I wish Dude would sit on her bed instead of on my bed.

If I set her leash on the table, maybe she’ll forget about going for a walk.

She saw me set it down, but she still thinks we’re going.

WHOM DO YOU LOVE?: WHO VERSUS WHOM

You’ve always wondered how to use who and whom. I know you have! Maybe you don’t sit on a grassy hill under an oak tree fondly wondering, but when you have to write a sentence that may need a whom, your blood pressure rises at least a degree or two.

I’ll have a quick and dirty trick for you later, but first I want you to actually understand the right way to use these words. The words who and whom are both pronouns. Knowing which word to choose also requires you to know the difference between subject and object because you use who when you are referring to the subject of a clause and whom when you are referring to the object of a clause.

For example, it is, “Whom did you step on?” if you are trying to figure out that I squished Squiggly because Squiggly is having the squishing done to him. He is the object. Similarly, you could ask me, “Whom do you love?” because you are asking about the object—the target of my love. I know, it’s shocking, but George Thorogood and the Destroyers were being grammatically incorrect when they belted out the song, “Who do you love?” It doesn’t sound as catchy, but it should have been “Whom do you love?”

So, when is it OK to use who? If you were asking about the subject of these sentences then you would use who.

Who loves you?

Who stepped on Squiggly?

In both these cases the one you are asking about is the subject—the one taking action—so you use who.

Now, back to that blood pressure. I’m not a doctor, and I don’t play one on TV, but I can still don my metaphorical white coat and dispense a prescription to lower your blood pressure: it’s a simple memory trick—we’ll call it the “him-lich” maneuver. It’s as easy as testing your sentence with the word him: if you can hypothetically answer your question with the word him, you need a whom.

Here’s an example: who/whom do you love? Imagine a guy you love—your father, your boyfriend, Chef Boyardee. I’m not here to judge you. The answer to the question Who/whom do you love? would be “I love him.” You’ve got a him, so the answer is whom: whom do you love?

I hope this isn’t the first time you’ve realized that you shouldn’t rely on George Thorogood and the Destroyers for grammar guidance.

Remember: him equals whom.

Whoever Versus Whomever

You can’t always use the him trick for whoever and whomever, but the same grammar rule holds true: you use whoever when you are talking about the subject (someone taking an action). In the next sentence, whoever (the person leaving the doughnuts) is taking the action.

· Whoever left these doughnuts in the conference room made our day.

You use whomever when you are talking about the object of a sentence, or the person who had something done to them. In the next sentence, whomever is the target of my action (seeing them).

· Whomever I see first will win the tickets.

* L. Barratt, “What Speakers Don’t Notice: Language Changes Can Sneak In,” in Innovation and Continuity in Language and Communication of Different Language Cultures, ed. Rudolf Muhr (New York: Peter Lang, 2006). Also in TRANS 16/2005: http://www.inst.at/trans/16Nr/01_4/barratt16.htm (accessed June 13, 2007).