The only business writing book you’ll ever need - Laura Brown, Rich Karlgaard 2019

The basics

Types of business writing

This section provides specific guidance for different genres of business writing. It doesn’t aim to be comprehensive. Rather, I’ve used input from the business writing survey I conducted for this book to confirm the kinds of things businesspeople write most often, and we’ll focus on those. Here you’ll find guidance on daily writing tasks, like e-mails and instant messages, as well as bigger tasks, like presentations and press releases. For all of them, you’ll find prompts about how to apply some or all of the Seven Steps as you write and refine.

THE BASICS

“Bad e-mail is the bane of my life.”

—SURVEY RESPONDENT

Ask businesspeople what they do for a living, and you’ll get all kinds of answers. Ask them what they do all day, and they’re likely say, “Deal with e-mail.” For most of us, e-mailing at work is as common as breathing. But it shouldn’t be as thoughtless.

DO YOU REALLY WANT TO SEND AN E-MAIL?

It’s easy to fire off an e-mail, but it’s not always the right thing to do. Before you write, consider whether you really should (see the decision tree in “To Write or Not to Write” here). In some situations, you should definitely choose not to send an e-mail.

Don’t send an e-mail when a phone call would work better. Endless rounds of e-mails to clarify, explain, and enlarge can often be prevented if you just pick up the phone.

Don’t fire off an e-mail when you’re angry. Give yourself time to cool off, so you don’t send something you’ll regret later.

Speaking of regret, if there’s anything in your e-mail—anything at all—that might hurt you or your organization, don’t do it. If you know or suspect that someone in your organization has done something illegal, unethical, unwise, or even just embarrassing, don’t e-mail about it. E-mail is not private. It’s discoverable in legal proceedings. Too many businesspeople are still far too careless about what they put in writing, and we see headlines about people incriminating themselves and their organizations in e-mails. There’s no excuse. If you’re not comfortable with reading about it on the front page of the New York Times, don’t put it in writing. Pick up the phone instead, or discuss the issue face-to-face.

MAKE SURE YOUR PURPOSE IS CLEAR

If I could offer only one piece of advice for e-mails, this would be it: make sure your reader knows why you’re writing. How many times have you plowed through a long e-mail trying to figure out what you’re supposed to do with it? How many times have you given up on a long e-mail before you’ve fully understood what it’s about? You don’t want your message on the receiving end of this kind of treatment.

We’re all moving fast when we compose and read e-mails, but it will actually save you time if you stop and think for a moment. Ask yourself, “What am I asking my reader to do?” The answer might be that you want your reader to take some kind of action. Or it might be that you want your reader to understand something. Whatever the answer is, put it into one sentence, and place a version of that sentence at the top of your message. You’ll save your reader and yourself a lot of confusion and follow-up.

WRITE FOR YOUR READER

Consideration for your reader starts with your subject line, which should be concise and specific. A good subject line can help readers prioritize messages and find them later. If your message is especially important, consider putting “important” or “response needed” in the subject line. (See the box “Hints and Tips for Effective E-mails” here for more suggestions about effective subject lines.)

Think from the point of view of your reader as you plan and write your e-mail. Anticipate objections, and make it easy for your reader to reply.

START STRONG AND SPECIFIC

A recent study based on analytics derived from billions of e-mails suggests, surprisingly, that readers’ attention spans seem to be increasing. Since 2011, the average time spent on reading an e-mail has grown by nearly 7 percent. That’s the good news. The bad news is that even with this growth, the average amount of time spent on each e-mail is only eleven seconds.*

With slightly over ten seconds of reader attention, it’s critical that you place your main point in the first three lines of your e-mail. If you count on your reader to scroll to the bottom of your message to get to the request, conclusion, or deadline, you risk losing him altogether.

GET YOUR CONTENT RIGHT

That short reader attention span also demands that you keep your message as brief as possible. Narrow down your content to the essentials, especially in an initial message. Follow-up messages can be longer, once you know that your reader is engaged.

You should limit each e-mail to one topic only. Secondary topics risk being buried at the bottom and never seen. The “one topic per e-mail” rule also makes it easier for you and your readers to search and find information in your in-boxes later.

FIX IT BEFORE YOU SEND IT

Before you send an e-mail, run though this quick checklist:

![]() Remember that e-mail isn’t private. Don’t put anything confidential in your message. If your e-mail contains anything that could incriminate or embarrass you, your colleagues, or your organization, delete it.

Remember that e-mail isn’t private. Don’t put anything confidential in your message. If your e-mail contains anything that could incriminate or embarrass you, your colleagues, or your organization, delete it.

![]() Is there anyone you ought to copy? Do you really need to copy the people you are copying?

Is there anyone you ought to copy? Do you really need to copy the people you are copying?

![]() If you’re forwarding an e-mail, be sure there’s nothing in it that you shouldn’t share. Especially if you’re forwarding a long thread, it’s worthwhile scrolling down to check.

If you’re forwarding an e-mail, be sure there’s nothing in it that you shouldn’t share. Especially if you’re forwarding a long thread, it’s worthwhile scrolling down to check.

![]() Is it clear to your reader in the first couple of lines what you are asking of her?

Is it clear to your reader in the first couple of lines what you are asking of her?

![]() Have you made your message as concise as possible?

Have you made your message as concise as possible?

Get Your E-mails Opened and Read

“It is very frustrating when I find out that my e-mail was not read (completely), just glossed over. Then again, I do the same thing until I am ready to respond to the e-mail, and then I read it. But if no response is requested . . . or I’m not interested in the topic or discussion . . . I’ll never know if a response was expected from me, because I haven’t actually read the e-mail.”

—SURVEY RESPONDENT

No one wants to send an e-mail that gets no reply. That has happened to all of us, and most of us have been guilty of failing to respond to a message we’ve received. When you send an e-mail, your message is competing with dozens, if not hundreds, of other messages in your reader’s in-box. How do you craft a message that your reader will actually open and read?

It starts with the subject line.

![]() Make your subject line as specific as possible.

Make your subject line as specific as possible.

![]() Use the subject line to state the response required from the reader (e.g., “read only” or “response requested”).

Use the subject line to state the response required from the reader (e.g., “read only” or “response requested”).

State your request within the first three lines of your message. Your opening should include:

![]() The context for the message and the request

The context for the message and the request

![]() The request itself

The request itself

![]() The deadline, if appropriate

The deadline, if appropriate

![]() The recipient’s incentive to continue to read to the bottom

The recipient’s incentive to continue to read to the bottom

Format your message for easy scanning.

![]() If your message is more than a few lines, use bullets and short paragraphs.

If your message is more than a few lines, use bullets and short paragraphs.

![]() Use bold to highlight deadlines and any milestones or intermediate deadlines.

Use bold to highlight deadlines and any milestones or intermediate deadlines.

Using these few simple tricks will make it easier for your reader to process and respond to your message. Over time, you’ll develop a reputation as an efficient communicator who doesn’t waste people’s time, and you’ll earn greater cooperation from your colleagues.

Hints and Tips for Effective E-mails

Patty Malenfant

In this day of short messages on Twitter and one-sentence captions on Facebook photos, the business world would do well to follow the same communication principles when using e-mail. To capture the interest of your reader so your e-mail will be read and you’ll receive the response needed, you must communicate briefly and efficiently. Everyone’s in-box is full, and you want your e-mail to be the one that gets read.

How do you do this? You need to use the e-mail subject line to state why you are sending the e-mail and what type of response you want. By inserting short action instructions before the subject, you can let the reader know what they need to do with your e-mail. Here are some examples:

![]() READ ONLY: This instruction lets the receiver know that the e-mail is just for their information; a response is not necessary, and no action is being requested. The receiver can hold this e-mail until a time in the near future to read it, but they do not have to act on it. Example: READ ONLY: ABC Client Accepts Proposal and Documents Being Finalized.

READ ONLY: This instruction lets the receiver know that the e-mail is just for their information; a response is not necessary, and no action is being requested. The receiver can hold this e-mail until a time in the near future to read it, but they do not have to act on it. Example: READ ONLY: ABC Client Accepts Proposal and Documents Being Finalized.

![]() RESPONSE REQUIRED: This instruction is for those e-mails where the receiver needs to do more than read—they need to reply. You are waiting for their response so you can take an action on your end. Example: RESPONSE REQUIRED: ABC Client Negotiated Contract Down $250.

RESPONSE REQUIRED: This instruction is for those e-mails where the receiver needs to do more than read—they need to reply. You are waiting for their response so you can take an action on your end. Example: RESPONSE REQUIRED: ABC Client Negotiated Contract Down $250.

![]() ACTION REQUIRED: This instruction lets the reader know that they need to do something with your e-mail beyond reading and responding—they need to take action. If you want to highlight a deadline for the action, you can add “Deadline” plus that date at the end of the subject line. Example: ACTION REQUIRED: Contract Proposal Final Approvals—Deadline July 15.

ACTION REQUIRED: This instruction lets the reader know that they need to do something with your e-mail beyond reading and responding—they need to take action. If you want to highlight a deadline for the action, you can add “Deadline” plus that date at the end of the subject line. Example: ACTION REQUIRED: Contract Proposal Final Approvals—Deadline July 15.

![]() EOM: “EOM” stands for “End of Message.” You will use this when you want to send only a quick message, comparable to a text message, but you are using e-mail. There is nothing in the body of the e-mail to review or requiring a response; in fact, there is nothing in the body of the e-mail at all, since the whole message is the subject line. Example: Wrapping up call—will be 15 minutes late for lunch EOM.

EOM: “EOM” stands for “End of Message.” You will use this when you want to send only a quick message, comparable to a text message, but you are using e-mail. There is nothing in the body of the e-mail to review or requiring a response; in fact, there is nothing in the body of the e-mail at all, since the whole message is the subject line. Example: Wrapping up call—will be 15 minutes late for lunch EOM.

Now that you have mastered the subject line of your e-mail, you need to be sure the content in the body succinctly communicates to your reader what they must know and/or do. You will have no more than three short paragraphs of two to four sentences each. Introduce the e-mail with a professional greeting and close with the same before your name and title, as appropriate for your organization.

In the first paragraph, give your reader any background information they need to know. The second paragraph follows with the challenge at hand or what is needed. Use the closing paragraph to cover any remaining questions or comments about the follow-up required.

By following these easy tips, you can now go forth and be sure that your e-mail will be the one everyone wants to read!

Patty Malenfant is a human resources leader for a Fortune 500 hospitality company in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area.

The Etiquette of E-mail Writing

Rosanne J. Thomas

Face-to-face communication is considered the best way to build relationships and deliver important messages. But the speed, convenience, and accuracy of text-based communication now make this mode the number one choice among professionals. We have a myriad of ways to communicate via text, but in business, e-mail is still the go-to method. However, there is a lot at stake with this mode of communication. Professionals at the highest levels have suffered extreme personal, financial, and health consequences as a result of carelessly crafted, hastily sent e-mails. And, of course, e-mail lives forever. How can we protect our reputations while maximizing the benefit of e-mail communication? Here are some guidelines.

![]() Apply the standard of “if you would not say it face-to-face, do not write it in an e-mail.” Studies show that people are much “braver” when communicating from behind a screen and that the lack of nonverbal cues often makes e-mails sound more aggressive than intended.

Apply the standard of “if you would not say it face-to-face, do not write it in an e-mail.” Studies show that people are much “braver” when communicating from behind a screen and that the lack of nonverbal cues often makes e-mails sound more aggressive than intended.

![]() Direct your message properly. Double-check e-mail addresses. Do not send “Reply All” messages unless absolutely necessary. Use “BCC” (blind carbon copy) ethically, and not to mislead your primary recipient into thinking that the e-mail exchange is confidential.

Direct your message properly. Double-check e-mail addresses. Do not send “Reply All” messages unless absolutely necessary. Use “BCC” (blind carbon copy) ethically, and not to mislead your primary recipient into thinking that the e-mail exchange is confidential.

![]() Read through e-mail threads completely before responding or forwarding. Use greater formality in e-mail composition with clients, company executives, persons from other cultures, and those you do not know well. Include an appropriate salutation and closing. Make sure sentences are properly structured. Observe the rules of capitalization and punctuation.

Read through e-mail threads completely before responding or forwarding. Use greater formality in e-mail composition with clients, company executives, persons from other cultures, and those you do not know well. Include an appropriate salutation and closing. Make sure sentences are properly structured. Observe the rules of capitalization and punctuation.

![]() Allow words to convey their meaning and emotion. Steer clear of emoticons and emojis in professional e-mails. Avoid using all capital letters, no capital letters, multiple exclamation points, bold typeface, bright colors, or flashing text.

Allow words to convey their meaning and emotion. Steer clear of emoticons and emojis in professional e-mails. Avoid using all capital letters, no capital letters, multiple exclamation points, bold typeface, bright colors, or flashing text.

![]() Proofread all e-mails. Use but do not rely solely upon grammar-check and spell-check tools. Read e-mails aloud to be sure they reflect your intended tone.

Proofread all e-mails. Use but do not rely solely upon grammar-check and spell-check tools. Read e-mails aloud to be sure they reflect your intended tone.

![]() Respond to e-mails promptly. If you cannot respond at least by the end of the day, have an “Out of Office” message automatically sent back to the recipient. This will help preserve the relationship.

Respond to e-mails promptly. If you cannot respond at least by the end of the day, have an “Out of Office” message automatically sent back to the recipient. This will help preserve the relationship.

Rosanne J. Thomas is the founder and president of Protocol Advisors, Inc., of Boston, Massachusetts, and the author of Excuse Me: The Survival Guide to Modern Business Etiquette (AMACOM, 2017).

Requests

Most communications in business are requests of one kind or another. Whether you’re asking for help or just for a bit of the reader’s attention, taking the time to plan and craft your request—rather than winging it—can significantly increase your chances of getting what you want and can save you time and hassle over the long run.

WHAT DO YOU WANT?

The fundamental purpose of any request—be it for assistance, information, or any other goal—is to enlist the cooperation of the reader. In order to do that, you need to be very clear about what you’re asking. This point sounds ridiculously simplistic, until you consider the number of messages you’ve received that have left you wondering, “What exactly do you want from me?” Unless your request is very straightforward, it’s worth taking a minute to clarify it in your own mind. If you’re asking for help, is it clear what kind of help you want? What, specifically, would you like the reader to do, and when?

WRITE FOR YOUR READER

Understanding your objective and stating it clearly is only half of the communication equation. The other half is understanding your reader: her potential attitude toward your request and what it might take for her to say yes. If you can anticipate her response, you can address any potential objections she might raise and motivate her to respond positively to your request.

START STRONG AND SPECIFIC

You should state your request early in your message, to orient the reader and allow her to decide whether to read your message now or wait until she can give it more time and attention.

GET YOUR CONTENT RIGHT

In addition to being clear about your request, you should be sure to provide any information your reader might need to make a decision. Include any necessary documentation related to your request. Let the reader know how you prefer to be contacted, if it’s not apparent.

Explaining the reason behind the request might help your reader respond favorably. Letting the reader know how important the request is to you can also motivate her to respond. How will you benefit if she grants your request? How might she benefit?

Your request should also include a deadline, if applicable and appropriate. Be sure your deadline is specific—asking for a response “ASAP” makes it easy for your reader to forget about your request. If you have a particularly tight deadline, explain the reason behind it. People will work harder to meet a deadline if they understand the reason for it.

CHECK IT BEFORE YOU SEND IT

Before you send off your request, check it over to make sure nothing feels wrong:

![]() Make sure your request comes early in your message and is clearly understandable to the reader.

Make sure your request comes early in your message and is clearly understandable to the reader.

![]() Use a courteous, not demanding, tone. Remember, you’re trying to gain cooperation from your reader.

Use a courteous, not demanding, tone. Remember, you’re trying to gain cooperation from your reader.

![]() Don’t take your reader or his attitude for granted, and don’t assume he’ll say yes to your request.

Don’t take your reader or his attitude for granted, and don’t assume he’ll say yes to your request.

![]() Remember to thank your reader.

Remember to thank your reader.

SAMPLE E-MAIL WITH A REQUEST

To: John Mottola

Date: April 17, 2019

Subject: Can you share configuration for BBL?

Hi Jack,

I’m writing a proposal for Evergreen, and I’m wondering if you could share the details of how you configured the package for the BBL installation. I’d like to do something similar for Evergreen. I want to submit the proposal on April 26.

I looked on the CRM, but I don’t see a lot of detail there. Can you shoot me an e-mail or spend a few minutes on the phone with me?

Thank you!

Kelby

Escalated Request When a Deadline Is Approaching

When a deadline is looming and you haven’t had the response to your request you need, it’s time to escalate. An escalated request follows the same basic principles as an initial request, but it’s pared down to the essentials and it makes a special appeal to the reader.

![]() Edit the subject line. When you send a follow-up to your request, edit the subject line to let the reader know the deadline is looming. If your original subject line was “Can you provide data for the report?,” you might edit it to say “Deadline Friday: Can you provide data for the report?” or “Reminder: Can you provide data for the report?”

Edit the subject line. When you send a follow-up to your request, edit the subject line to let the reader know the deadline is looming. If your original subject line was “Can you provide data for the report?,” you might edit it to say “Deadline Friday: Can you provide data for the report?” or “Reminder: Can you provide data for the report?”

![]() Keep it short. Your follow-up request should be brief and should contain the most essential information the reader needs to carry out what’s being asked. Don’t get bogged down in details.

Keep it short. Your follow-up request should be brief and should contain the most essential information the reader needs to carry out what’s being asked. Don’t get bogged down in details.

![]() Acknowledge that the reader is busy.

Acknowledge that the reader is busy.

![]() Let the reader know why the request is important to you or to the organization.

Let the reader know why the request is important to you or to the organization.

![]() Let the reader know why you’re asking him and not someone else—what can he do that no one else can do for you?

Let the reader know why you’re asking him and not someone else—what can he do that no one else can do for you?

![]() Restate the deadline, and explain why it’s important.

Restate the deadline, and explain why it’s important.

![]() Offer to help. If there’s any way you can make it easier for the reader, offer to do so.

Offer to help. If there’s any way you can make it easier for the reader, offer to do so.

![]() If appropriate, indicate that you’ll follow up again shortly, maybe with a phone call.

If appropriate, indicate that you’ll follow up again shortly, maybe with a phone call.

![]() Be sure to say “thank you.”

Be sure to say “thank you.”

SAMPLE E-MAIL WITH AN ESCALATED REQUEST

To: John Mottola

Date: April 23, 2019

Subject: Deadline Friday: Can you share configuration for BBL?

Hi Jack,

Just following up on this. I’d like to use the same configuration you used for BBL in my proposal to Evergreen, which is due on Friday the 26th. I know you’re swamped with JWB right now, but your insight here could really help us close the deal. Even just the server information would make a big difference.

I’ll give you a call tomorrow.

Thank you for your help!

Kelby

Bad News Messages

Good news messages are easy to write, but conveying bad news can be rough. The key here is to save the reader’s feelings to the greatest extent possible. That means opening with a buffer—a thank-you, if appropriate, or some kind of statement of appreciation. To avoid giving the reader false hope, though, you should transition very quickly to a diplomatic and kind statement of the bad news. If appropriate, it’s fine to express regret over the news, but not an apology. If there’s some hope of good news in the future, make sure you communicate that hope conservatively, without making a firm commitment. Close with a statement of goodwill.

Dear Erik,

Thank you for submitting the proposal for creating a task force on recruiting. You suggested some great ideas, but unfortunately we have to prioritize expanding the product line this season and we don’t have the resources right now.

I would like to return to this idea once we have the product line resolved. Let’s stay in touch about it.

Thanks again,

Mack

Instant Messages

Instant messaging or chatting is nearly as quick and easy as talking, but it isn’t talking—it’s writing, and it requires a little care. No matter what IM or chat app you’re using, these guidelines can help make your messages more productive and efficient.

IS IM THE RIGHT MEDIUM?

IM is almost too easy to use. It’s the default medium of communication for a lot of us at work, but it’s not always the most appropriate one. Before you ping a colleague, it’s a good idea to slow down long enough to ask yourself a few questions: “Do I really need this answer immediately? Is it worth interrupting my colleague to get it in this way? Would it be more efficient to save up a few questions and ask them all at once? Would it be better to let my colleague answer in his own time instead of insisting on a response now?” It’s also worth considering what kind of record, if any, you’ll need of the discussion with your colleague. Some messaging programs preserve your message history when you shut down your computer, but others don’t. So if you want an easily accessible record of your exchange, instant messaging might not be the best choice of medium.

MIND YOUR MANNERS

Respect the availability status of your colleagues, and if it’s red, don’t send a message unless it’s an absolute emergency. Your colleague might be in the middle of a Webex or videoconference and not appreciate the distraction on the screen, or she might be concentrating on finishing a task.

You also need to be aware of tone when you’re sending messages. It’s easy to slip into a very casual tone. That’s fine when you and your colleague are on the same wavelength, but take care you don’t use a super-casual tone with someone you don’t know well. Be especially careful if you have more than one chat window or channel going at once.

Remember that you’re at work. Instant messaging can be fun, but you’re not on Facebook or Instagram. Respect your colleagues’ time, and exercise restraint when sharing to group chats or channels; remember that everyone is trying to get their work done.

WATCH WHAT YOU SAY

Even when you’re pinging with good work friends, remember that instant messages are official business communications. They are not confidential. They’re the property of your company, and many companies monitor them. You’re probably cautious about cursing in the office; you should exercise the same caution when you’re messaging. One popular instant messaging program warns users: “Keep your conversations limited to what can be safely said in an elevator or a crowded restaurant.” Keep it appropriate.

USING INSTANT MESSAGING EFFICIENTLY

A few little tricks can help improve the efficiency of your instant messaging. Before you launch into a long message, ask your colleague if she’s there and available. Make your “Are you there?” message more specific by letting your colleague know what you want to ping about. Instead of “Hey, got a second?” try “Hey, got a second to review the XYZ agreement?” or “Hey, got a second to read something for me?” or “Hey, got a second to show me how to use that software?” And be frank about what you’re asking for; don’t type “qq?” if what you really want is to discuss whether or not to fire a vendor or some other large topic.

Presentations

Thirty million PowerPoint presentations are given every day throughout the world. How can you make yours memorable?

PINPOINT YOUR PURPOSE

Attention can wander during a presentation, so it’s important that you know exactly what you want to get from yours. As an exercise, try creating a one-sentence objective for the presentation, such as “By the end of the presentation, I want the audience to understand that our solution offers more tools than the competition’s does and can be customized for their needs” or “By the end of the presentation, I want x members of the audience to request an onsite demo” or “By the end of the presentation, I want to have cleared the obstacles to partnering on this project.” Try to make your objective as active as possible, in order to avoid building a presentation that’s essentially an information dump. What do you want your audience to do as a result of seeing your presentation?

WRITE FOR YOUR AUDIENCE

As you work on your slides, think from the point of view of the people who will have to look at them. What are they expecting from your presentation? What information do they need? How would you feel sitting through this presentation? How can you make the slides easy for the audience to read and ensure that they reinforce your main points? Let your understanding of your audience’s needs guide the preparation of your slides.

ORIENT YOUR AUDIENCE AT THE BEGINNING

The opening of your presentation is an especially critical moment. Presumably you have everyone’s attention at the beginning. No one has had a chance to get bored, to get distracted by their phone, or to grow worried about the work they’re not getting done because they’re sitting in this presentation. Use this moment to let your audience know what will be covered in the presentation. Insert an outline slide at the beginning, and return to it throughout the presentation to help your audience with transitions and help them pace themselves in terms of energy and attention.

GET YOUR CONTENT RIGHT

There’s a strong impulse when you’re preparing your slides to include too much content. Research has shown that people typically remember only four slides from a twenty-page deck.† That’s not very encouraging news if you’re putting your heart and soul into an informative presentation, but from a strategic point of view, it’s good to know. Rather than packing your presentation full of facts, you’re better off choosing a few key points you want your audience to remember, and organizing the presentation around those. Think of your PowerPoint deck as a set of prompts for your performance rather than as a repository for complete information.‡

Set up your slides as a visual aid for when you’re making a speech or presentation, not as a trove of data. When presented with a very text-heavy slide, people will typically space out or stop listening and read the slide (people can read faster than you can talk). If you want to provide detailed information to your audience, you can make and distribute a leave-behind deck that contains your entire talk. For the presentation itself, keep your slides concise and the focus on you.

USE VISUALS EFFECTIVELY

Think visually as you create your slides.§ There’s no need to convey information only through words—think about how you can use images and graphics to get your points across. But be careful with graphs and charts: don’t present graphics that are too small or detailed for the audience to see easily or understand quickly. If you have an important chart or table that is complex, present a simplified version of it on your slide and give the audience the full version, printed on paper, to examine more closely.

IF SOMETHING FEELS WRONG, FIX IT

Proofread your slides very carefully. Noticing a typo for the first time when you’re standing in front of a group is a ghastly experience, and it makes you look bad. If possible, ask someone who is not familiar with the content to proof the presentation for you.

Allow yourself time to rehearse the presentation and revise it, even if you feel pretty comfortable about the content. Notice transitions that aren’t smooth, areas where your content seems thin, sections that drag. Rehearsing can give you more confidence and will improve your audience’s experience by helping you improve your slides.

SLIDE REVISION CHECKLIST

![]() Choose readable fonts, and limit the number of fonts you use. Stick to a few basic, easy-to-read fonts, no more than two different fonts per slide.

Choose readable fonts, and limit the number of fonts you use. Stick to a few basic, easy-to-read fonts, no more than two different fonts per slide.

![]() Use animation and sound sparingly and only if they support the message of your presentation. If they enhance the meaning and clarity of your presentation, use them. If they compete with your content, don’t.

Use animation and sound sparingly and only if they support the message of your presentation. If they enhance the meaning and clarity of your presentation, use them. If they compete with your content, don’t.

![]() In bullet points, use parallel grammatical constructions to help your audience follow your ideas.

In bullet points, use parallel grammatical constructions to help your audience follow your ideas.

![]() Use formatting like bold and italics sparingly and consistently. Too much of this kind of formatting can make your slides hard to read.

Use formatting like bold and italics sparingly and consistently. Too much of this kind of formatting can make your slides hard to read.

For sample presentations, please visit me at www.howtowriteanything.com.

Creating Visuals

Not all business communication occurs through writing—a lot occurs through visuals. In fact, words aren’t always your best tool. Sometimes data is easier to understand if it’s represented graphically. You don’t have to be a graphic designer to learn the language of visual communication.

CHOOSE THE RIGHT GRAPHIC

There are lots of graphics options for you to choose from: photos and other images, as well as different kinds of charts and graphs. The type of graphic you choose will depend on your data and the story you want to tell with it.

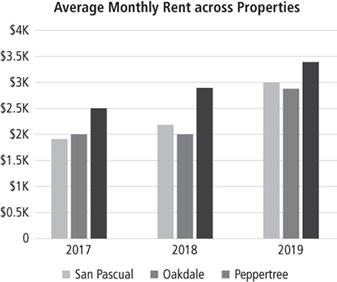

COLUMN CHART

A column chart lets you compare values using vertical bars.

BAR CHART

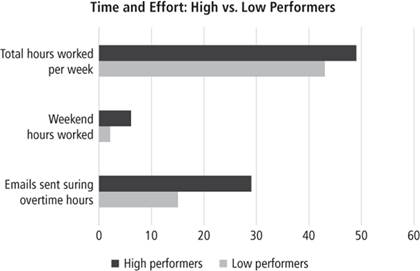

A bar chart lets you compare values using horizontal bars. The layout of a bar chart makes it better suited than a column chart for data with long labels.

STACKED BAR CHART

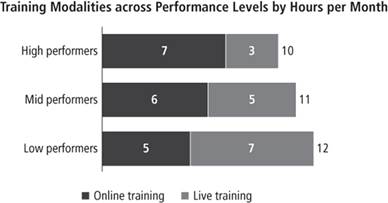

A stacked bar chart breaks out the components of a total number, so you can compare segments as well as totals.

LINE CHART

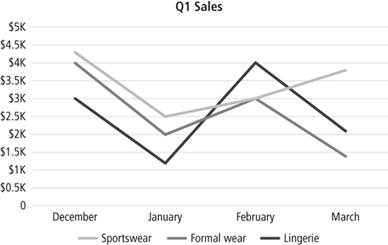

A line chart is used to track and compare values over time. It can show small increments of time more effectively than a bar chart can.

PIE CHART

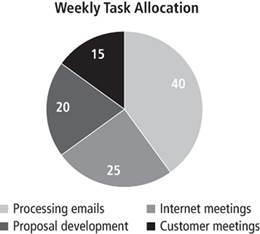

A pie chart is a circle divided into slices, useful for showing numerical proportion.

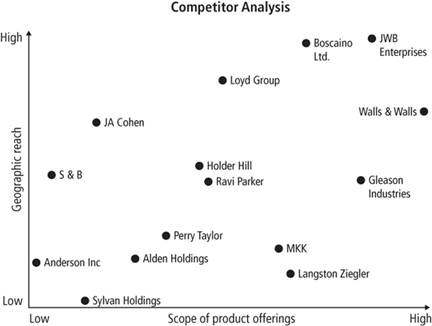

DOT OR SCATTER PLOT

A dot or scatter plot shows data positioned on vertical and horizontal axes. It might be used to show the effect of one variable on another. In this example, a company is using a scatter plot to evaluate its competitors on two dimensions: geographic reach and scope of product offerings.

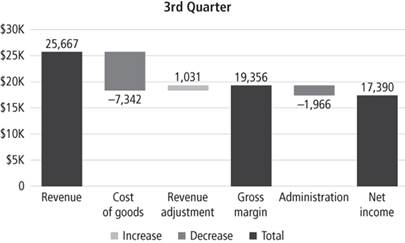

WATERFALL CHART

Waterfall charts show how the cumulative effects of different inputs contribute to a net value.

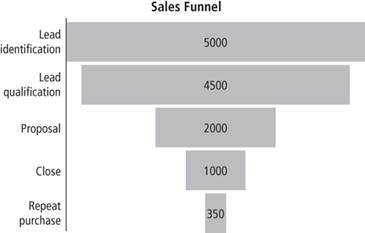

FUNNEL CHART

Funnel charts are often used in sales to show the potential revenue for each stage in the sales process. They can help you identify areas in the process where value is at greatest risk of being lost, and they can help identify an unhealthy sales funnel. In this example, the qualification process is not weeding out many prospects, which leads to many rejected proposals.

MAKE SURE YOUR WORDS AND GRAPHICS COMPLEMENT EACH OTHER

When you use words and graphics together, you need to make sure they work together in harmony and support each other. The first and most obvious rule is that the content of your words and graphics should be consistent. For example, if you’re calling out some numbers from a graphic, make sure those numbers are accurate.

Avoid repeating the content of the graphic in your prose. If you’re simply going to rehash the contents of the graphic in writing, there’s not much point in including the graphic. Instead, strategically use information from your graphics to support the arguments you’re making in prose.

Proposals

Businesses of all kinds create proposals for potential customers and clients—for example, to bid for work, to outline the scope of a job, or to state a price. The content of a sales proposal will vary widely, depending on the kind of business you’re in, and most businesses have a standard format they use. Check to see if your organization has a proposal template, then use these suggestions to make it as compelling as possible.

GET THE ASK CLEAR

If you write a lot of proposals, it’s tempting to go on automatic pilot, filling in the various sections with numbers and other details. That approach is probably fine a lot of the time, especially if you provide the same service or product over and over. But it’s worth mentioning here that you should pay attention to your prospective customer, and make sure your proposal reflects your understanding of their needs.

WRITE FOR YOUR READER

If you’re preparing a proposal, it’s probably at the request of someone you’ve talked to at your potential customer. Needless to say, you should consider carefully all the information your contact has given you. You should also go beyond that. Depending on the situation, it’s very likely that others in the organization will review your proposal. Who might they be, and what might they be concerned about? If your contact person is not the decision-maker, it might be worthwhile to ask who else will review the proposal.

Everyone reviewing a proposal will be concerned about cost, but don’t assume that cost is the only factor. Really think about your reader’s needs, and ensure that your proposal addresses them.

GET THE CONTENT RIGHT

Decide how you want to present estimates in your proposal. Sometimes estimates are binding. In other cases, the proposal contains a clause stating that the final cost may vary depending on a variety of circumstances. You should date your proposal and include an expiration date for the price quoted, so that you don’t bind yourself to a price forever and there’s no misunderstanding with the customer.

If there’s a risk of cost overruns, address that risk directly and outline the factors that might cause them, including unanticipated circumstances on the job or changes in the customer’s requirements.

If you feel the customer isn’t entirely sure what they want, consider providing several different estimates for different options. Some companies routinely include add-ons in proposals, which can lead to more business, but add-ons can also annoy customers if they feel they are being upsold. Any add-ons you suggest should clearly address the customer’s needs as you understand them.

CHECK IT BEFORE YOU SEND IT

If you’re using a template for your proposal or repurposing a proposal you’ve used before, have a look before you send it to make sure you’re including complete information and that you’re not inadvertently leaving in the details of previous proposals, including the names of other companies and prices for other jobs.

Also check to see that you’ve included everything, and that your numbers add up accurately. Errors can be embarrassing and sometimes costly.

For sample proposals, please visit me at www.howtowriteanything.com.

RFPs

Some organizations will prepare and circulate a Request for Proposals (RFP) in search of a vendor to do a particular job, usually for jobs of a significant size. Some organizations that use public money are mandated to use an RFP in the bidding process.

If you’re responding to an RFP, be very sure you follow its requirements exactly. Any deviation can throw you out of the running without further consideration.

A long sales proposal in response to an RFP may include the following elements:

Letter of transmittal

Title page

Executive summary

Description of current problem

Description of current method

Description of proposed method

Analytical comparison of current and proposed methods

Equipment requirements

Cost analysis

Delivery schedule

Summary of benefits

Breakdown of responsibilities

Description of vendor, including team bios

Vendor’s promotional literature

Contract