Practical argument: A text and anthology - Laurie G. Kirszner, Stephen R. Mandell 2019

Finding and evaluating sources

Using sources to support your argument

AT ISSUE

Is Technology a Serious Threat to Our Privacy?

The internet and social media have become deeply woven into our lives, to the point where Facebook has over 2.23 billion users worldwide. Not surprisingly, social media sites have become a primary tool for people—from marketers to cybercriminals—who want to access personal information, for better and for worse. High profile data breaches have raised concerns too. Facebook faced a scandal in 2018 when it revealed that over 87 million of its users’ data had been shared with Cambridge Analytica, a political consulting firm that sought data on American political behavior.

Most people agree that such breaches are bad and that protecting privacy is important. But they disagree over approaches to the problem. Some want stricter government regulation; others think free markets will address the issue; still, others argue that the only way to ensure privacy is for individuals to avoid sharing personal information online.

Later in this chapter, you will evaluate several sources to determine whether they are acceptable for an argumentative essay about technology and privacy. In Chapter 9, you will learn how to integrate sources into an essay on this topic. In Chapter 10, you will see an MLA paper on one aspect of the topic: whether it is ethical for employers to access information posted on job applicants’ social-networking sites. Finally, in Chapter 11, you will learn how to use sources responsibly while considering the question, “Where should we draw the line with plagiarism?”

Finding Sources

In some argumentative essays, you can use your own ideas as evidence in support of your position. In many others, however, you have to do research—collect information (in both print and electronic form) from magazines, newspapers, books, journals, and other sources—to supplement your own ideas.

The obvious question is, “How does research help you to construct better arguments?” The answer is that research enables you to explore the ideas of others, consider multiple points of view, and expand your view of your subject. By doing so, you get a better understanding of the issues surrounding your topic, and as a result, you are able to develop a strong thesis and collect the facts, examples, statistics, quotations, and expert opinion that you will need to support your points. In addition, by taking the time to find reliable, up-to-date sources, you demonstrate to readers that your discussion is credible and that you are someone worth listening to. In short, doing research enables you to construct intelligent, authoritative, and convincing arguments.

As you do research, keep in mind that your argumentative essay should not be a collection of other people’s ideas. It should present an original thesis that you develop with your own insights and opinions. You use the information you get from your research to provide additional support for your thesis and to expand your discussion. In other words, your voice, not the voices of your sources, should control the discussion.

Finding Information in the Library

When most students do research, they immediately go to the internet. Unfortunately, by doing this, they ignore the most reliable source of high-quality information available to them: their college library.

Your college library contains both print and electronic resources that you cannot find anywhere else. Although the internet gives you access to an almost unlimited amount of material, it does not offer the consistently high level of reliable information found in your college library. For this reason, you should always begin your research by surveying the resources of the library.

The best way to access your college library is to visit its website, which is the gateway to a great deal of information—for example, its online catalog, electronic databases, and reference works.

NOTE

Many libraries have a discovery service that enables you to use a single search box to access a wide variety of content—for example, the physical items held by a library as well as content from e-books, journal articles, government documents, and electronic databases. Most discovery services return high-quality results quickly and (like Google) rank them according to relevancy.

The Online Catalog: The online catalog lists all the books, journals, newspapers, magazines, and other material housed in the library. Once you gain access to this catalog, you can type in keywords that will lead you to sources related to your topic.

Online Databases: All college libraries subscribe to databases—collections of digital information that you access through a keyword search. The library’s online databases enable you to retrieve bibliographic citations as well as the full text of articles from hundreds of publications. Some of these databases—for example, Expanded Academic ASAP and Proquest Research Library—provide information on a wide variety of topics. Others—for example, Business Source Premier and Sociological Abstracts—provide information on a particular subject area. Before selecting a database, check with the reference librarian to determine which will be most useful for your topic.

Reference Works: All libraries contain reference works—sources of accurate and reliable information such as dictionaries, encyclopedias, and almanacs. These reference works are available both in print and in electronic form. General encyclopedias—such as the New Encyclopaedia Britannica and the Columbia Encyclopedia—provide general information on a wide variety of topics. Specialized reference works—such as Facts on File and the World Almanac—and special encyclopedias—such as the Encyclopedia of Law and Economics—offer detailed information on specific topics.

NOTE

Although a general encyclopedia (print or electronic) can provide an overview of your topic, encyclopedia articles do not usually treat topics in enough depth for college-level research. Be sure to check your instructor’s guidelines before you use a general encyclopedia in your research.

Finding Information on the Internet

Although the internet gives you access to a vast amount of information, it has its limitations. For one thing, because anyone can publish on the web, you cannot be sure if the information found there is trustworthy, timely, or authoritative. Of course, there are reliable sources of information on the web. For example, the information on your college library’s website is reliable. In addition, Google Scholar provides links to some scholarly sources that are as good as those found in a college library’s databases. Even so, you have to approach this material with caution; some articles accessed through Google Scholar are pay-per-view, and others are not current or comprehensive.

USING GOOGLE SCHOLAR

Google Scholar is a valuable research resource. If you use it, however, you should be aware of its drawbacks:

§ It includes some non-scholarly publications. Because it does not accurately define scholar, some material may not conform to academic standards of reliability.

§ It does not index all scholarly journals. Many academic journals are available only through a library’s databases and are not accessible on the internet.

§ Google Scholar is uneven across scholarly disciplines—that is, it includes more information from some disciplines than others. In addition, Google Scholar does not perform well for publications before 1990.

§ Google Scholar does not screen for quality. Because Google Scholar uses an algorithm, not a human being, to select sources, it does not always filter out junk journals.

§ Some of the articles in Google Scholar are pay-per-view. Before you pay to download an article, check to see if your college library gives you free access.

A search engine—such as Google—helps you to locate and to view documents that you search for with keywords. Different types of search engines are suitable for different purposes:

§ General-Purpose Search Engines: General-purpose search engines retrieve information on a great number of topics. They cast the widest possible net and bring in the widest variety of information. The disadvantage of general-purpose search engines is that you get a great deal of irrelevant material. Because each search engine has its own unique characteristics, you should try a few of them to see which you prefer. The most popular general-purpose search engines are Google, Bing, Yahoo!, and Ask.com.

§ Specialized Search Engines: Specialized search engines focus on specific subject areas or on a specific type of content—for example, business, government, or health services. The advantage of specialized search engines is that they eliminate the need for you to wade through pages of irrelevant material. By focusing your search on a specific subject area, you are more likely to locate information on your particular topic. You can find a list of specialized search engines on the Search Engine List (thesearchenginelist.com).

§ Metasearch Engines: Because each search engine works differently, results can (and do) vary. For this reason, if you limit yourself to a single search engine, you can miss a great deal of useful information. Metasearch engines solve this problem by taking the results of several search engines and presenting them in a simple, no-nonsense format. The most popular metasearch engines are Dogpile, ixquick, MetaGer, MetaCrawler, and Sputtr.

Evaluating Sources

When you evaluate a source, you assess the objectivity of the author, the credibility of the source, and its relevance to your argument. Whenever you locate a source—print or electronic—you should always take the time to evaluate it.

Although a librarian or an instructor has screened the print and electronic sources in your college library for general accuracy and trustworthiness, you cannot simply assume that these sources are suitable for your particular writing project. Material that you access online presents particular problems. Although some material on the internet (for example, journal articles that are published in both print and digital format) is reliable, other material (for example, personal websites and blogs) may be unreliable and unsuitable for your research. Remember, if you use an untrustworthy source, you undercut your credibility.

To evaluate sources, you use the same process that you use when you evaluate anything else. For example, if you are thinking about buying a laptop computer, you use several criteria to help you make your decision—for example, price, speed, memory, reliability, and availability of technical support. The same is true for evaluating research sources. You can use the following criteria to decide whether a source is appropriate for your research:

§ Accuracy

§ Credibility

§ Objectivity

§ Currency

§ Comprehensiveness

§ Authority

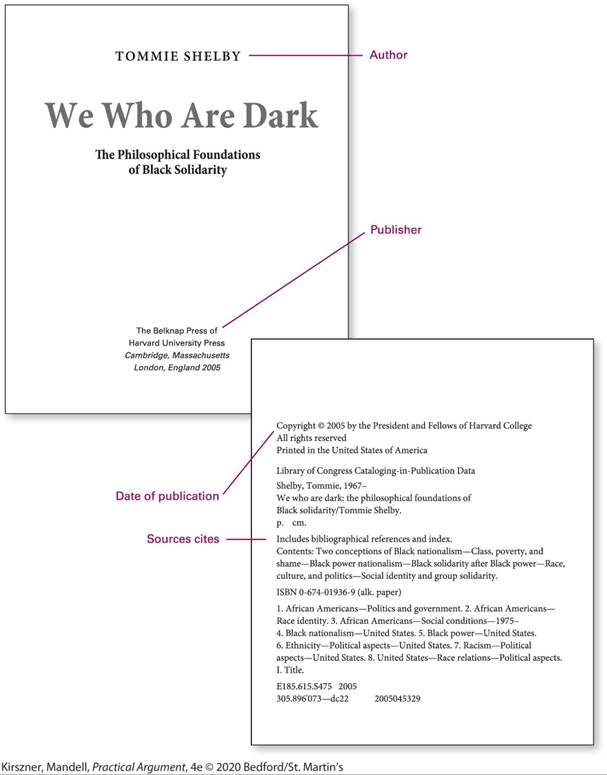

The illustrations on page 291 show where to find information that can help you evaluate a source.

Accuracy

A source is accurate when it is factual and free of errors. One way to judge the accuracy of a source is to compare the information it contains to that same information in several other sources. If a source has factual errors, then it probably includes other types of errors as well. Needless to say, errors in spelling and grammar should also cause you to question a source’s general accuracy.

You can also judge the accuracy of a source by checking to see if the author cites sources for the information that is discussed. Documentation can help readers determine both the quality of information in a source and the range of sources used. It can also show readers what sources a writer has failed to consult. (Failure to cite an important book or article should cause you to question the writer’s familiarity with a subject.) If possible, verify the legitimacy of some of the books and articles that a writer cites by seeing what you can find out about them online. If a source has caused a great deal of debate or if it is disreputable, you will probably be able to find information about the source by researching it on Google.

Credibility

A source is credible when it is believable. You can begin checking a source’s credibility by determining where a book or article was published. If a university press published the book, you can be reasonably certain that it was peer reviewed—read by experts in the field to confirm the accuracy of the information. If a commercial press published the book, you will have to consider other criteria—the author’s reputation and the date of publication, for example—to determine quality. If your source is an article, see if it appears in a scholarly journal—a periodical aimed at experts in a particular field—or in a popular magazine—a periodical aimed at general readers. Journal articles are almost always acceptable research sources because they are usually documented, peer reviewed, and written by experts. (They can, however, be difficult for general readers to understand.) Articles in high-level popular magazines, such as the Atlantic and the Economist, may also be suitable—provided experts wrote them. However, articles in lower-level popular magazines—such as Sports Illustrated and Time—may be easy to understand, but they are seldom acceptable sources for research.

The title page reads as follows.

[Center alignment, in caps] Tommie Shelby [Note reads, Author.]

[Center alignment, larger font] We Who Are Dark

[Center alignment] The Philosophical Foundations of Black Solidarity

The text at the bottom of the page is center aligned and reads as follows.

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England 2005

[Note pointing to ’The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press’ reads, Publisher.]

The citation page reads as follows.

Copyright (copyright symbol) 2005 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College [Note pointing to ’2005’ reads, Date of publication.]

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shelby, Tommie, 1967—

We who are dark: the philosophical foundations of Black solidarity/Tommie Shelby.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index. [Margin note reads, Sources cites.]

Contents: Two conceptions of Black nationalism —Class, poverty, and shame —Black power nationalism —Black solidarity aft¬er Black power —Race, culture, and politics—Social identity and group solidarity.

ISBN 0-674-01936-9 (alk. paper)

1. African Americans—Politics and government. 2. African Americans— Race identity. 3. African Americans—Social conditions—1975— 4. Black nationalism—United States. 5. Black power—United States. 6. Ethnicity—Political aspects—United States. 7. Racism—Political aspects —United States. 8. United States—Race relations—Political aspects.

I. Title.

E185.615.S475 2005

305.896'073—dc22 2005045329

You can determine how well respected a source is by reading reviews written by critics. You can find reviews of books by consulting Book Review Digest—either in print or online—which lists books that have been reviewed in at least three magazines or newspapers and includes excerpts of reviews. In addition, you can consult the New York Times Book Review website—www.nytimes.com/pages/books/index.html—to access reviews printed by the newspaper since 1981. (Both professional and reader reviews are also available at Amazon.com.)

Finally, you can determine the influence of a source by seeing how often other scholars in the field refer to it. Citation indexes indicate how often books and articles are mentioned by other sources in a given year. This information can give you an idea of how important a work is in a particular field. Citation indexes for the humanities, the social sciences, and the sciences are available both in print and electronically.

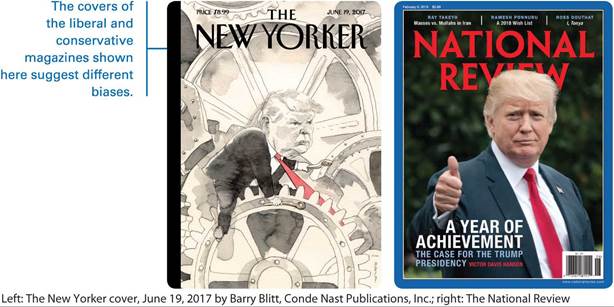

Objectivity

A source is objective when it is not unduly influenced by a writer’s personal opinions or feelings. Ideally, you want to find sources that are objective, but to one degree or another, all sources are biased. In short, all sources—especially those that take a stand on an issue—reflect the opinions of their authors, regardless of how hard they may try to be impartial. (Of course, an opinion is perfectly acceptable—as long as it is supported by evidence.)

The cover page of The New Yorker, June 19, 2017 by Barry Blitt, Conde Nast Publications, Inc. shows President Daniel Trump jammed in a set of gears with his tie stuck and dragging him.The cover page of the National Review, February 5, 2018 shows President Daniel Trump giving the thumbs-up sign. The title reads, A Year of Achievement. The Case for the Trump Presidency.A note to the cover pages reads, The covers of the liberal and conservative magazines shown here suggest different biases.

As a researcher, you should recognize that bias exists and ask yourself whether a writer’s assumptions are justified by the facts or are simply the result of emotion or preconceived ideas. You can make this determination by looking at a writer’s choice of words and seeing if the language is slanted or by reviewing the writer’s points and seeing if his or her argument is one-sided. Get in the habit of asking yourself whether you are being offered a legitimate point of view or simply being fed propaganda.

Currency

A source is current when it is up to date. (For a book, you can find the date of publication on the copyright page, as shown on page 291. For an article, you can find the date on the front cover of the magazine or journal.) If you are dealing with a scientific subject, the date of publication can be very important. Older sources might contain outdated information, so you want to use the most up-to-date source that you can find. For other subjects—literary criticism, for example—the currency of the information may not be as important as it is in the sciences.

Comprehensiveness

A source is comprehensive when it covers a subject in sufficient depth. The first thing to consider is whether the source deals specifically with your subject. (If it treats your subject only briefly, it will probably not be useful.) Does it treat your subject in enough detail? Does the source include the background information that you need to understand the discussion? Does the source mention other important sources that discuss your subject? Are facts and interpretations supported by the other sources you have read, or are there major points of disagreement? Finally, does the author include documentation?

How comprehensive a source needs to be depends on your purpose and audience as well as on your writing assignment. For a short essay for an introductory course, editorials from the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal might give you enough information to support your argument. If you are writing a longer essay, however, you might need to consult journal articles (and possibly books) about your subject.

Authority

A source has authority when a writer has the expertise to write about a subject. Always try to determine if the author is a recognized authority or simply a person who has decided to write about a particular topic. For example, what other books or articles has the author written? Has your instructor ever mentioned the author’s name? Is the author mentioned in your textbook? Has the author published other works on the same subject or on related subjects? (You can find this information on Amazon.com.)

You should also determine if the author has an academic affiliation. Is he or she a faculty member at a respected college or university? Do other established scholars have a high opinion of the author? You can often find this information by using a search engine such as Google or by consulting one of the following directories:

· Contemporary Authors

· Directory of American Scholars

· International Who’s Who

· National Faculty Directory

· Who’s Who in America

· Wilson Biographies Plus Illustrated

![]()

EXERCISE 8.1 EVALUATING SOURCES

Assume that you are preparing to write an argumentative essay on the topic of whether information posted on social-networking sites threatens privacy. Read the sources that follow, and evaluate each source for accuracy, credibility, objectivity, currency, comprehensiveness, and authority.

§ Zeynep Tufekci, “The Privacy Debacle”

§ David N. Cicilline and Terrell McSweeny, “Competition Is at the Heart of Facebook’s Privacy Problem”

§ Daniel Lyons, “Facebook: Privacy Problems and PR Nightmare”

THE PRIVACY DEBACLE

ZEYNEP TUFEKCI

This essay appeared in the January 30, 2018 issue of the New York Times.

Did you make a New Year’s resolution to exercise more? Perhaps you downloaded a fitness app to help track your workouts, maybe one that allows you to share that data online with your exercise buddies?

If so, you probably checked a box to accept the app’s privacy policy. For most apps, the default setting is to share data with at least the company; for many apps the default is to share data with the public. But you probably didn’t even notice or care. After all, what do you have to hide?

For users of the exercise app Strava, the answer turns out to be a lot more than they realized. Since November, Strava has featured a global “heat map” showing where its users jogged or walked or otherwise traveled while the app was on. The map includes some three trillion GPS data points, covering more than 5 percent of the earth. Over the weekend, a number of security analysts showed that because many American military service members are Strava users, the map inadvertently reveals the locations of military bases and the movements of their personnel.

Perhaps more alarming for the military, similar patterns of movement appear to possibly identify stations or airstrips in locations where the United States is not known to have such operations, as well as their supply and logistics routes. Analysts noted that with Strava’s interface, it is relatively easy to identify the movements of individual soldiers not just abroad but also when they are back at home, especially if combined with other public or social media data.

“Data privacy is not like a consumer good.”

Apart from chastening the cybersecurity experts in the Pentagon, the Strava debacle underscores a crucial misconception at the heart of the system of privacy protection in the United States. The privacy of data cannot be managed person-by-person through a system of individualized informed consent.

Data privacy is not like a consumer good, where you click “I accept” and all is well. Data privacy is more like air quality or safe drinking water, a public good that cannot be effectively regulated by trusting in the wisdom of millions of individual choices. A more collective response is needed.

Part of the problem with the ideal of individualized informed consent is that it assumes companies have the ability to inform us about the risks we are consenting to. They don’t. Strava surely did not intend to reveal the GPS coordinates of a possible Central Intelligence Agency annex in Mogadishu, Somalia—but it may have done just that. Even if all technology companies meant well and acted in good faith, they would not be in a position to let you know what exactly you were signing up for.

Another part of the problem is the increasingly powerful computational methods called machine learning, which can take seemingly inconsequential data about you and, combining them with other data, can discover facts about you that you never intended to reveal. For example, research shows that data as minor as your Facebook “likes” can be used to infer your sexual orientation, whether you use addictive substances, your race and your views on many political issues. This kind of computational statistical inference is not 100 percent accurate, but it can be fairly close—certainly close enough to be used to profile you for a variety of purposes.

A challenging feature of machine learning is that exactly how a given system works is opaque. Nobody—not even those who have access to the code and data—can tell what piece of data came together with what other piece of data to result in the finding the program made. This further undermines the notion of informed consent, as we do not know which data results in what privacy consequences. What we do know is that these algorithms work better the more data they have. This creates an incentive for companies to collect and store as much data as possible, and to bury the privacy ramifications, either in legalese or by playing dumb and being vague.

What can be done? There must be strict controls and regulations concerning how all the data about us—not just the obviously sensitive bits—is collected, stored and sold. With the implications of our current data practices unknown, and with future uses of our data unknowable, data storage must move from being the default procedure to a step that is taken only when it is of demonstrable benefit to the user, with explicit consent and with clear warnings about what the company does and does not know. And there should also be significant penalties for data breaches, especially ones that result from underinvestment in secure data practices, as many now do.

Companies often argue that privacy is what we sacrifice for the supercomputers in our pockets and their highly personalized services. This is not true. While a perfect system with no trade-offs may not exist, there are technological avenues that remain underexplored, or even actively resisted by big companies, that could allow many of the advantages of the digital world without this kind of senseless assault on our privacy.

With luck, stricter regulations and a true consumer backlash will force our technological overlords to take this issue seriously and let us take back what should be ours: true and meaningful informed consent, and the right to be let alone.

COMPETITION IS AT THE HEART OF FACEBOOK’S PRIVACY PROBLEM

DAVID N. CICILLINE AND TERRELL McSWEENY

This editorial was published in WIRED on April 24, 2018.

Our data are being turned against us. Data powers disinformation campaigns attacking democratic institutions. It is used to foment division and turn us against one another. Cambridge Analytica harvested the personal information of approximately 87 million Facebook users not just to target would-be voters with campaign ads but, as former Cambridge Analytica staffer Christopher Wylie put it to the New York Times, to “fight a culture war in America.”

Consumers are trusting companies with vast amounts of intimate data and receiving very little assurance that it will be properly handled and secured. In turn, our data are used to power the connected services we use, and depending on the platform or app, are sold to advertisers. Sometimes, as in the case of Facebook, we receive services for free in exchange for our data.

But in this system individuals bear the risk that their data will be handled properly—and have little recourse when it is not.

It is time for a better deal. Americans should have rights to and control over their data. If we don’t like a service, we should be free to move our data to another.

But Facebook’s control of consumers’ information and attention is substantial and durable. There are more than 200 million monthly active Facebook users in the United States, and the company already owns two potential competitors—Instagram, a social photo-sharing company, and WhatsApp, a messaging service. Facebook also collects and mines consumers’ data across the internet, even for consumers without Facebook accounts.

It is also difficult and time-consuming to move data between platforms.

The ability to control this data isn’t just part of Facebook’s business model; it’s also a vital component of creating choice, competition, and innovation online. The value of Facebook’s network grows and depends on the number of people who are on it.

But unlike other networks—such as your phone company, which is required to let you keep your existing phone number when switching service providers and make calls regardless of the carrier you use—Facebook and other technology companies also have the final say over whether you can take your key information to a competing service or communicate across different platforms.

The result of this asymmetry in control? The same network effect that creates value for people on Facebook can also lock them into Facebook’s walled garden by creating barriers to competition. People who may want to leave Facebook are less likely to do so if they aren’t able to seamlessly rebuild their network of contacts, photos, and other social graph data on a competing service or communicate across services.

This friction effectively blocks new competitors—including platforms that might be more protective of consumers’ privacy and give consumers more control over their data—from entering the market. That’s why we need procompetitive policies that give power back to Americans through more rights and control over their data.

“It is critical that we restore Americans’ control over their data.”

Privacy and competition are becoming increasingly interdependent conditions for protecting rights online. It is critical that we restore Americans’ control over their data through data portability and interoperability requirements.

Data portability would reduce barriers to entry online by giving people tools to export their network—rather than merely downloading their data—to competing platforms with the appropriate privacy safeguards in place.

Before it was acquired by Facebook, Instagram owed much of its immense growth to the open APIs that allowed users of Twitter and Facebook to import their friend networks to a new, competing service.

And today, you can already use your Facebook account to import your profile and contacts on Spotify and some other social apps.

Interoperability would facilitate competition by enabling communication across networks in the way the Open Internet was designed to work.

The bottom line: Unless consumers gain meaningful control over their personal information, there will continue to be persistent barriers to competition and choice online.

Of course, there need to be guardrails in place to protect the privacy and security of users.

Legislators and regulators also need to more extensively reform data security and privacy law to improve privacy, transparency, and accountability online—particularly among data brokers and credit reporting agencies like Equifax—and create more transparency in political advertisements and spending online.

But at a minimum, Americans should have real control over their data. A procompetitive solution to reducing barriers to entry online will encourage platforms to compete on providing better privacy, control, and rights for consumers.

FACEBOOK: PRIVACY PROBLEMS AND PR NIGHTMARE

DANIEL LYONS

This essay was published by Newsweek on May 25, 2010.

Facebook’s 26-year-old founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg may be a brilliant software geek, but he’s lousy at public relations. In fact the most amazing thing about Facebook’s current crisis over user privacy is how bad the company’s PR machine is.

Instead of making things better, Facebook’s spin doctors just keep making things worse. Instead of restoring trust in Facebook, they just make the company seem more slippery and sneaky. Best example is an op-ed that Zuckerberg published earlier this week in the Washington Post, a classic piece of evasive corporate-speak that could only have been written by PR flacks.

In the op-ed, Zuckerberg pretends to believe that the biggest concern users have is how complicated Facebook’s privacy controls are. He vows to remedy that by making things simpler.

But the real problem isn’t the complexity of Facebook’s privacy controls. The problem is the privacy policy itself. Of course Zuckerberg knows this. He’s many things, but stupid isn’t one of them. The real point of his essay, in fact, was that Facebook has no intention of rolling back the stuff that people are really upset about.

“The problem is the privacy policy itself.”

The company did revise its privacy policy this week, and some privacy experts were appeased, while others said Facebook still has more work to do. For one thing, if you want to keep Facebook from sharing your info with Facebook apps and connected websites, you have to opt out—meaning, the default setting is you’re sharing. From my perspective a better policy would just to have everything set to private, by default.

But at this point the details of the policy aren’t even the real issue. The real issue is one of perception, which is that sure, Facebook made some changes, but only because they had no choice. The perception is that Facebook got caught doing something wrong, and sheepishly backed down. That is the narrative that will be attached to this latest episode, and it’s not a good one for Facebook.

As for that vapid op-ed earlier in the week, Facebook might also have thought twice about publishing the piece in the Washington Post, since Donald E. Graham, chairman of the Post, also sits on Facebook’s board of directors and has been an important mentor to Zuckerberg.

Everyone involved, including Graham himself, says nobody pulled any strings, that Facebook just submitted the piece to the Post without Graham’s knowledge, and the Post chose to run it because it was of interest to readers.

In other words we are asked to believe that though Graham and Zuckerberg are close friends, and presumably Zuckerberg has been consulting with Graham (and other board members) over the privacy crisis, Zuckerberg and his team never mentioned to Graham the fact that Facebook was going to publish an op-ed in Graham’s newspaper.

Okay. Maybe that’s true. Nevertheless, of all the newspapers in the world, why choose the one that’s owned by one of your board members? Chalk up another clunker for the Facebook PR team.

Facebook’s real problem now is that Zuckerberg and his PR reps have made so many ludicrous statements that it’s hard to believe anything they say. They’ve claimed that they’re only changing privacy policies because that is what members want. They’ve said, when the current crisis began, that there was nothing wrong with the policy itself—the problem was simply that Facebook hadn’t explained it well enough.

One gets the impression that Facebook doesn’t take any of this stuff very seriously. It just views the complaints as little fires that need to be put out. The statements Facebook issues aren’t meant to convey any real information—they’re just blasts from a verbal fire extinguisher, a cloud of words intended not to inform, but to smother.

Just keep talking, the idea seems to be, and it doesn’t matter what you say. In fact the more vapid and insincere you can be, the better. Eventually the world will get sick of the sound of your voice, and the whiners will give up and go away.

Of course Facebook wouldn’t need to do any of this spinning if it would just fix its privacy policy. It could, for example, go back to the policy it used in 2005, which said your info would only be shared with your friends.

No doubt Zuckerberg has performed a bunch of calculations, weighing the cost of the bad publicity against the benefit of getting hold of all that user data. And he’s decided to push on and endure the black eye.

Which tells you all you need to know about Mark Zuckerberg, and the value of the information that Facebook is collecting.

![]()

EXERCISE 8.2 WRITING AN EVALUATION

Write a one- or two-paragraph evaluation of each of the three sources you read for Exercise 8.1. Be sure to support your evaluation with specific references to the sources.

Evaluating Websites

The internet is like a freewheeling frontier town in the old West. Occasionally, a federal marshal may pass through, but for the most part, there is no law and order, so you are on your own. On the internet, literally anything goes—exaggerations, misinformation, errors, and even complete fabrications. Some websites contain reliable content (for example, journal articles that are published in both print and digital format), but many do not. The main reason for this situation is that there is no authority—as there is in a college library—who evaluates sites for accuracy and trustworthiness. That job falls to you, the user.

Another problem is that websites often lack important information. For example, a site may lack a date, a sponsoring organization, or even the name of the author of the page. For this reason, it is not always easy to evaluate the material you find there.

ACCEPTABLE VERSUS UNACCEPTABLE INTERNET SOURCES

Before you use an internet source, you should consider if it is acceptable for college-level work:

Acceptable Sources

§ Websites sponsored by reliable organizations, such as academic institutions, the government, and professional organizations

§ Websites sponsored by academic journals and reputable magazines or newspapers

§ Blogs by recognized experts in their fields

§ Research forums

Unacceptable Sources

§ Information on anonymous websites

§ Information found in chat rooms or on discussion boards

§ Personal blogs written by authors of questionable expertise

§ Information on personal web pages

§ Poorly written web pages

When you evaluate a website (especially when it is in the form of a blog or a series of posts), you need to begin by viewing it skeptically—unless you know for certain that it is reliable. In other words, assume that its information is questionable until you establish that it is not. Then apply the same criteria you use to evaluate any sources—accuracy, credibility, objectivity, currency, comprehensiveness, and authority.

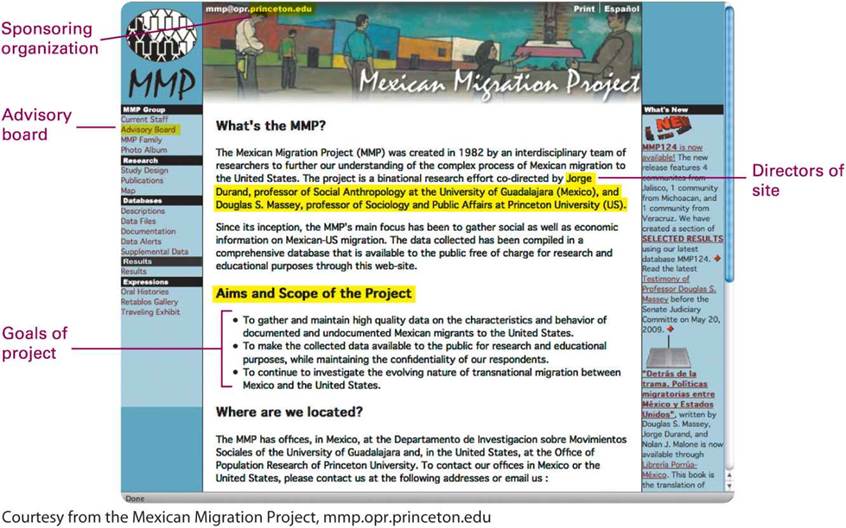

The web page pictured on page 302 shows where to find information that can help you evaluate a website.

Accuracy

Information on a website is accurate when it is factual and free of errors. Information in the form of facts, opinions, statistics, and interpretations is everywhere on the internet, and in the case of Wiki sites, this information is continually being rewritten and revised. Given the volume and variety of this material, it is a major challenge to determine its accuracy. You can assess the accuracy of information on a website by asking the following questions:

§ Does the site contain errors of fact? Factual errors—inaccuracies that relate directly to the central point of the source—should immediately disqualify a site as a reliable source.

§ Does the site contain a list of references or any other type of documentation? Reliable sources indicate where their information comes from. The authors know that people want to be sure that the information they are using is accurate and reliable. If a site provides no documentation, you should not trust the information it contains.

§ Does the site provide links to other sites? Does the site have links to reliable websites that are created by respected authorities or sponsored by trustworthy institutions? If it does, then you can conclude that your source is at least trying to maintain a certain standard of quality.

§ Can you verify information? A good test for accuracy is to try to verify key information on a site. You can do this by checking it in a reliable print source or on a good reference website such as Encyclopedia.com.

Credibility

Information on a website is credible when it is believable. Just as you would not naively believe a stranger who approached you on the street, you should not automatically believe a site that you randomly encounter on the web. You can assess the credibility of a website by asking the following questions:

§ Does the site list authors, directors, or editors? Anonymity—whether on a website or on a blog—should be a red flag for a researcher who is considering using a source.

§ Is the site refereed? Does a panel of experts or an advisory board decide what material appears on the website? If not, what standards are used to determine the suitability of content?

§ Does the site contain errors in grammar, spelling, or punctuation? If it does, you should be on the alert for other types of errors. If the people maintaining the site do not care enough to make sure that the site is free of small errors, you have to wonder if they will take the time to verify the accuracy of the information presented.

§ Does an organization sponsor the site? If so, do you know (or can you find out) anything about the sponsoring organization? Use a search engine such as Google to determine the purpose and point of view of the organization.

The center panel at the top shows an illustration of a Mexican town and Mexicans. At the top left corner the text reads, mmp at o p r dot Princeton dot edu. [Note pointing to highlighted text ’princeton dot edu’ reads, Sponsoring organization.] At the top right corner the text reads, Print; Español. The text at the center panel reads as follows.

[Sub-heading] What’s the MMP?

The Mexican Migration Project (MMP) was created in 1982 by an interdisciplinary team of researcher to further our understanding of the complex process of Mexican migration to the United States. The project is a binational research effort co-directed by Jorge Durand, professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Guadalajara (Mexico), and Douglas S. Massey, professor of Sociology and Public Affairs at Princeton University (U S). [The last sentence from ’Jorge Durand’ is highlighted and a note pointing to it reads, Directors of site.]

Since its inception, the MMP’s main focus has been to gather social as well as economic information on Mexican-U S migration. The data collected has been compiled in a comprehensive database that is available to the public free of charge for research and educational purposes through this web-site.

[Sub-heading, highlighted] Aims and Scope of the Project

[Bullet point] To gather and maintain high quality data on the characteristics and behavior of documented and undocumented Mexican migrants to the United States.

[Bullet point] To make the collected data available to the public for research and educational purposes, while maintaining the confidentiality of our respondents.

[Bullet point] To continue to investigate the evolving nature of transnational migration between Mexico and the United States.

[Annotation to the bullet points reads, Goals of project.]

[Sub-heading] Where are we located?

The MMP has offices, in Mexico, at the Departmento de Investigacion sobre Movimientos Sociales of the University of Guadalajara and, in the United States, at the Office of Population Research of Princeton University. To contact our offices in Mexico or the United States, please contact us at the following addresses or email us (colon)

The left panel of the webpage shows the logo of Mexican Migration Project (MMP). Below it are sub-headings with links as follows.

[Sub-heading] MMP Group:

Current Staff

Advisory Board [Advisory Board is highlighted and a callout reads, Advisory board]

MMP Family

Photo Album

[Sub-heading] Research

Study Design

Publications

Map

[Sub-heading] Databases:

Descriptions

Data Files

Documentation

Data Alerts

Supplemental Data

[Sub-heading] Results:

Results

[Sub-heading] Expressions:

Oral Histories

Retablos Gallery

Traveling Exhibit

The right panel of the webpage is headed ’What’s New’ with a graphic design showing the heading. The text reads as follows.

MMP 1 2 4 is now available! The new release features 4 communities from Jalisco, 1 community from Michoacan, and 1 community from Veracruz. We have created a section of Selected Results using our latest database MMP 1 2 4.

Read the latest Testimony of Professor Douglas S. Massey before the Senate Judiciary Committe on May 20, 2009.

A photo of a book.

(Open quotes) Detrás de la trama. Politicas migratorias entre México y Estados Unidos (closequotes), written by Douglas S. Massey, Jorge Durand, and Nolan J. Malone is now available through Libería Porrúa-México. This book is the translation of

Objectivity

Information on a website is objective when it limits the amount of bias that it displays. Some sites—such as those that support a particular political position or social cause—make no secret of their biases. They present them clearly in their policy statements on their home pages. Others, however, try to hide their biases—for example, by referring only to sources that support a particular point of view and not mentioning those that do not.

Keep in mind that bias does not automatically disqualify a source. It should, however, alert you to the fact that you are seeing only one side of an issue and that you will have to look further to get a complete picture. You can assess the objectivity of a website by asking the following questions:

§ Does advertising appear on the site? If the site contains advertising, check to make sure that the commercial aspect of the site does not affect its objectivity. The site should keep advertising separate from content.

§ Does a commercial entity sponsor the site? A for-profit company may sponsor a website, but it should not allow commercial interests to determine content. If it does, there is a conflict of interest. For example, if a site is sponsored by a company that sells organic products, it may include testimonials that emphasize the virtues of organic products and ignore information that is skeptical of their benefits.

§ Does a political organization or special-interest group sponsor the site? Just as you would for a commercial site, you should make sure that the sponsoring organization is presenting accurate information. It is a good idea to check the information you get from a political site against information you get from an educational or a reference site—Ask.com or Encyclopedia.com, for example. Organizations have specific agendas, and you should make sure that they are not bending the truth to satisfy their own needs.

§ Does the site link to strongly biased sites? Even if a site seems trustworthy, it is a good idea to check some of its links. Just as you can judge people by the company they keep, you can also judge websites by the sites they link to. Links to overly biased sites should cause you to reevaluate the information on the original site.

USING A SITE’S URL TO ASSESS ITS OBJECTIVITY

A website’s URL (uniform resource locator) can give you information that can help you assess the site’s objectivity.

· Look at the domain name to identify sponsorship. Knowing a site’s purpose can help you determine whether a site is trying to sell you something or just trying to provide information. The last part of a site’s URL can tell you whether a site is a commercial site (.com and .net), an educational site (.edu), a nonprofit site (.org), or a governmental site (.gov, .mil, and so on).

· See if the URL has a tilde (~) in it. A tilde in a site’s URL indicates that information was published by an individual and is unaffiliated with the sponsoring organization. Individuals can have their own agendas, which may be different from the agenda of the site on which their information appears or to which it is linked.

AVOIDING CONFIRMATION BIAS

Confirmation bias is a tendency that people have to accept information that supports their beliefs and to ignore information that does not. For example, people see false or inaccurate information on websites, and because it reinforces their political or social beliefs, they forward it to others. Eventually, this information becomes so widely distributed that people assume that it is true. Numerous studies have demonstrated how prevalent confirmation bias is. Consider the following examples:

§ A student doing research for a paper chooses sources that support her thesis and ignores those that take the opposite position.

§ A prosecutor interviews witnesses who establish the guilt of a suspect and overlooks those who do not.

§ A researcher includes statistics that confirm his hypothesis and excludes statistics that do not.

When you write an argumentative essay, do not accept information just because it supports your thesis. Realize that you have an obligation to consider all sides of an issue, not just the side that reinforces your beliefs.

Currency

Information on a website is current when it is up-to-date. Some sources—such as fiction and poetry—are timeless and therefore are useful whatever their age. Other sources, however—such as those in the hard sciences—must be current because advances in some disciplines can quickly make information outdated. For this reason, you should be aware of the shelf life of information in the discipline you are researching and choose information accordingly. You can assess the currency of a website by asking the following questions:

§ Does the website include the date when it was last updated? As you look at web pages, check the date on which they were created or updated. (Some websites automatically display the current date, so be careful not to confuse this date with the date the page was last updated.)

§ Are all links on the site live? If a website is properly maintained, all the links it contains will be live—that is, a click on the link will take you to other websites. If a site contains a number of links that are not live, you should question its currency.

§ Is the information on the site up to date? A site might have been updated, but this does not necessarily mean that it contains the most up-to-date information. In addition to checking when a website was last updated, look at the dates of the individual articles that appear on the site to make sure they are not outdated.

Comprehensiveness

Information on a website is comprehensive when it covers a subject in depth. A site that presents itself as a comprehensive source should include (or link to) the most important sources of information that you need to understand a subject. (A site that leaves out a key source of information or that ignores opposing points of view cannot be called comprehensive.) You can assess the comprehensiveness of a website by asking the following questions:

§ Does the site provide in-depth coverage? Articles in professional journals—which are available both in print and online—treat subjects in enough depth for college-level research. Other types of articles—especially those in popular magazines and in general encyclopedias, such as Wikipedia—are often too superficial (or untrustworthy) for college-level research.

§ Does the site provide information that is not available elsewhere? The website should provide information that is not available from other sources. In other words, it should make a contribution to your knowledge and do more than simply repackage information from other sources.

§ Who is the intended audience for the site? Knowing the target audience for a website can help you to assess a source’s comprehensiveness. Is it aimed at general readers or at experts? Is it aimed at high school students or at college students? It stands to reason that a site that is aimed at experts or college students will include more detailed information than one that is aimed at general readers or high school students.

Authority

Information on a website has authority when you can establish the legitimacy of both the author and the site. You can determine the authority of a source by asking the following questions:

§ Is the author an expert in the field that he or she is writing about? What credentials does the author have? Does he or she have the expertise to write about the subject? Sometimes you can find this information on the website itself. For example, the site may contain an “About the Author” section or links to other publications by the author. If this information is not available, do a web search with the author’s name as a keyword. If you cannot confirm the author’s expertise (or if the site has no listed author), you should not use material from the site.

§ What do the links show? What information is revealed by the links on the site? Do they lead to reputable sites, or do they take you to sites that suggest that the author has a clear bias or a hidden agenda? Do other reliable sites link back to the site you are evaluating?

§ Is the site a serious publication? Does it include information that enables you to judge its legitimacy? For example, does it include a statement of purpose? Does it provide information that enables you to determine the criteria for publication? Does the site have a board of advisers? Are these advisers experts? Does the site include a mailing address and a phone number? Can you determine if the site is the domain of a single individual or the effort of a group of individuals?

§ Does the site have a sponsor? If so, is the site affiliated with a reputable institutional sponsor, such as a governmental, educational, or scholarly organization?

![]()

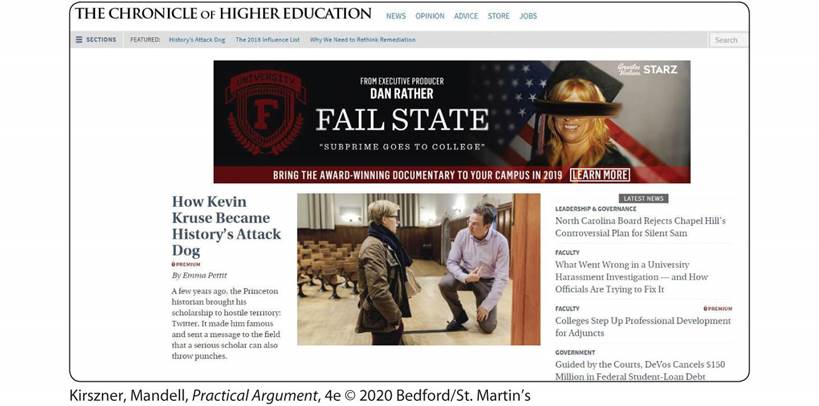

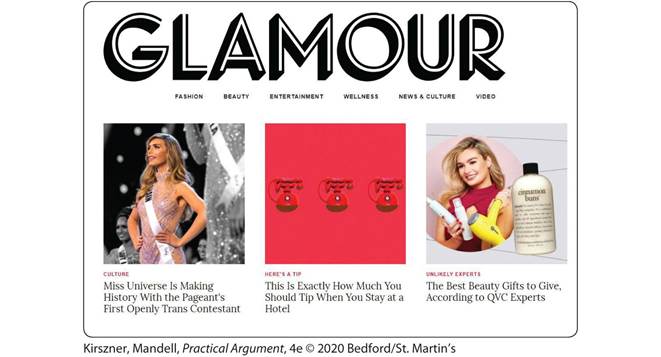

EXERCISE 8.3 CONSIDERING TWO HOME PAGES

Consider the following two home pages—one from the website for the Chronicle of Higher Education, a publication aimed at college instructors and administrators, and the other from the website for Glamour, a publication aimed at general readers. Assume that on both websites, you have found articles about privacy and social-networking sites. Locate and label the information on each home page that would enable you to determine the suitability of using information from the site in your paper.

The title bar at the top of the home page reads, The Chronicle of Higher Education on the left, and shows the links to News, Opinion, Advice, Store, and Jobs beside it.

The menu bar below it shows the Sections tab, followed by Featured news articles, and a Search icon on the right.

The home page shows an ad of Fail State. Below it is an article on the left hand along with a photo. On the right hand is a series of news articles under the heading Latest News.

At the top of the home page is the name of the magazine Glamour in large font. Below it is the menu bar showing the following genres: Fashion, Beauty, Entertainment, Wellness, News and Culture, and Video.

The page shows three articles from left to right as follows: Culture: Miss Universe Is Making History With the Pageant’s First Openly Trans Contestant along with a photo of the Miss Universe; Here’s a Tip: This Is Exactly How Much You Should Tip When You Stay at a Hotel along with an illustration of three telephones; and Unlikely Experts: The Best Beauty Gifts to Give, According to Q V C Experts along with a photo of a woman holding cosmetic items in an inset and a bottle of cinnamon buns.

![]()

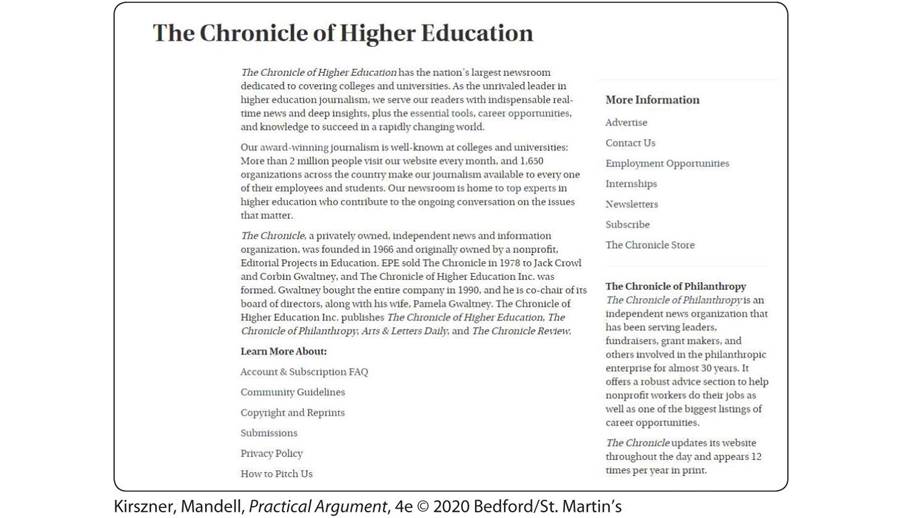

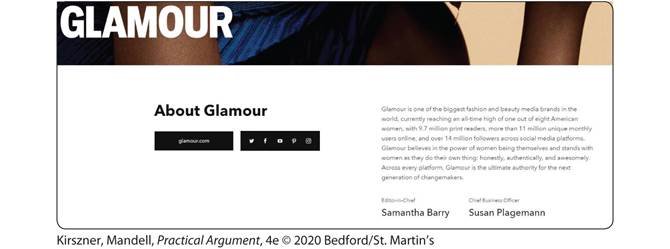

EXERCISE 8.4 CONSIDERING TWO MISSION STATEMENTS

Here are the mission statements—statements of the organizations’ purposes—from the websites for the Chronicle of Higher Education and Glamour, whose home pages you considered in Exercise 8.3. What additional information can you get from these mission statements? How do they help you to evaluate the sites as well as the information that might appear on the sites?

The text at the top reads, The Chronicle of Higher Education. (Boldface, large font)

The following text reads,

[New paragraph] The Chronicle of Higher Education (in italics) has the nation’s largest newsroom dedicated to covering colleges and universities. As the unrivaled leader in higher education journalism, we serve our readers with indispensable real-time news and deep insights, plus the essential tools, career opportunities, and knowledge to succeed in a rapidly changing world.

[New paragraph] Our award-winning journalism is well-known at colleges and universities: More than 2 million people visit our website every month, and 1,650 organizations across the country make our journalism available to every one of their employees and students. Our newsroom is home to top experts in higher education who contribute to the ongoing conversation on the issues that matter.

[New paragraph] (in italics) The Chronicle, a privately owned, independent news and information organization, was founded in 1966 and originally owned by a nonprofit, Editorial Projects in Education, E P E sold The Chronicle in 1978 to Jack Crowl and Corbin Gwaltney, and The Chronicle of Higher Education Inc. was formed. Gwaltney bought the entire company in 1990, and he is co-chair of its board of directors, along with his wife, Pamela Gwaltney. The Chronicle of Higher Education Inc. publishes The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Chronicle of Philanthropy, Arts and Letters Daily, and The Chronicle Review. [The names of the magazines are in italics.]

Learn More about:

Account and Subscription FAQ

Community Guidelines

Copyright and Reprints

Submissions

Privacy Policy

How to Pitch Us

On the right hand, the text reads as follows.

More Information

Advertise

Contact Us

Employment Opportunities

Internships

Newsletters

Subscribe

The Chronicle Store

The text below it reads as follows.

The Chronicle of Philanthropy

The Chronicle of Philanthropy is an independent news organization that has been serving leaders, fundraisers, grant makers, and others involved in the philanthropic enterprise for almost 30 years. It offers a robust advice section to help nonprofit workers do their jobs as well as one of the biggest listings of career opportunities.

The Chronicle updates its website throughout the day and appears 12 times per year in print.

On the left side, the text reads, About Glamour. Below it is the website link and the links to its social pages, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Pinterest, and Instagram.

On the right side, the text reads, Glamour is one of the biggest fashion and beauty media brands in the world, currently reaching an all-time high of one out of eight American women, with 9.7 million print readers, more than 11 million unique monthly users online, and over 14 million followers across social media platforms. Glamour believes in the power of women being themselves and stands with women as they do their own thing: honestly, authentically, and awesomely. Across every platform, Glamour is the ultimate authority for the next generation of changemakers.

Editor-in-Chief, Samantha Barry. Chief Business Officer, Susan Plagemann.

![]()

EXERCISE 8.5 EVALUATING MATERIAL FROM WEBSITES

Each of the following sources was found on a website: Bart Lazar, “Why We Need a Privacy Label on the Internet,” page 308; Douglass Rushkoff, “You Are Not Facebook’s Customer,” page 309; and Igor Kuksov, “All Ears: The Dangers of Voice Assistants,” page 309.

Assume that you are preparing to write an essay on the topic of whether information posted on social-networking sites threatens privacy. First, visit the websites on which the articles below appear, and evaluate each site for accuracy, credibility, objectivity, currency, comprehensiveness, and authority. Then, using the same criteria, evaluate each source.

WHY WE NEED A PRIVACY LABEL ON THE INTERNET

BART LAZAR

This piece appeared on Politico on April 25, 2018.

As Facebook and other internet companies deal with the fallout from security lapses before and after the presidential election, lawmakers are increasingly concerned that lax oversight is resulting in major violations of Americans’ privacy. When Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg testified before two committees earlier this month, even GOP lawmakers typically opposed to regulations said new rules to restrict the actions of Facebook and other internet companies may be necessary.

To finish reading this article and evaluate its source, Google search for Bart Lazar’s “Why We Need a Privacy Label on the Internet” or go to: https://www.politico.com/agenda/story/2018/04/25/internet-privacy-label-000656.

YOU ARE NOT FACEBOOK’S CUSTOMER

DOUGLASS RUSHKOFF

This article was posted to Douglass Rushkoff’s personal website.

The ire and angst accompanying Facebook’s most recent tweaks to its interface are truly astounding. The complaints rival the irritation of AOL’s dial-up users back in the mid-’90s, who were getting too many busy signals when they tried to get online. The big difference, of course, is that AOL’s users were paying customers. In the case of Facebook, which we don’t even pay to use, we aren’t the customers at all.

To continue reading this article and evaluate its source, Google search for Douglass Rushkoff’s “You Are Not Facebook’s Customer” or go to: www.rushkoff.com/you-are-not-facebooks-customer/.

ALL EARS: THE DANGERS OF VOICE ASSISTANTS

IGOR KUKSOV

This article originally appeared on Kaspersky Lab’s website on February 28, 2017.

Nowadays the proverb “the walls have ears” is not as metaphoric as it used to be.

“The telescreen received and transmitted simultaneously. Any sound that Winston made, above the level of a very low whisper, would be picked up by it. … There was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment.” That is George Orwell’s description of Big Brother’s spying devices in the novel 1984.

To continue reading this article and evaluate its source, Google search for Igor Kuksov’s “All Ears: The Dangers of Voice Assistants” or go to: www.kaspersky.com/blog/voice-recognition-threats/14134/.

![]()

EXERCISE 8.6 EVALUATING A BLOG POST

Read the blog post below and then answer the questions on page 311.

SHOULD ATHLETES HAVE SOCIAL MEDIA PRIVACY? ONE BILL SAYS YES

SAM LAIRD

This article first appeared on Mashable.com on February 6, 2012.

Should universities be allowed to force student athletes to have their Facebook and Twitter accounts monitored by coaches and administrators?

No, says a bill recently introduced into the Maryland state legislature.

The bill would prohibit institutions “from requiring a student or an applicant for admission to provide access to a personal account or service through an electronic communications device”—by sharing usernames, passwords, or unblocking private accounts, for example.

Introduced on Thursday, Maryland’s Senate Bill 434 would apply to all students but particularly impact college sports. Student-athletes’ social media accounts are frequently monitored by authority figures for instances of indecency or impropriety, especially in high-profile sports like football and men’s basketball.

“Student-athletes’ social media accounts are frequently monitored.”

In one example, a top football recruit reportedly put his scholarship hopes in jeopardy last month after a series of inappropriate tweets.

The bill’s authors say that it is one of the first in the country to take on the issue of student privacy in the social media age, according to the New York Times.

Bradley Shear is a Maryland lawyer whose work frequently involves sports and social media. In a recent post to his blog, Shear explained his support for Senate Bill 434 and a similar piece of legislation that would further extend students’ right to privacy on social media.

“Schools that require their students to turn over their social media user names and/or content are acting as though they are based in China and not in the United States,” Shear wrote.

But legally increasing student-athletes’ option to social media privacy could also help shield the schools themselves from potential lawsuits.

On his blog, Shear uses the example of Yardley Love, a former University of Virginia women’s lacrosse player who was allegedly murdered by her ex-boyfriend, who played for the men’s lacrosse team.

If the university was monitoring the lacrosse teams’ social media accounts and missed anything that could have indicated potential violence, it “may have had significant legal liability for negligent social media monitoring because it failed to protect Love,” Shear wrote.

On the other hand, if the school was only monitoring the accounts of its higher-profile football and basketball players, Shear wrote, then that could have been considered discrimination and the university “may have been sued for not monitoring the electronic content of all of its students.”

Do you think universities should be allowed to force their athletes into allowing coaches and administrators to monitor their Facebook and Twitter accounts?

Questions

1. What steps would you take to determine whether Laird’s information is accurate?

2. How could you determine whether Laird is respected in his field?

3. Is Laird’s blog written for an audience that is knowledgeable about his subject? How can you tell?

4. Do you think this blog post is a suitable research source? Why or why not?

5. This blog post was written in 2012. Do you think it is still relevant today? Why or why not?