Practical argument: A text and anthology - Laurie G. Kirszner, Stephen R. Mandell 2019

Summarizing, paraphrasing, quoting, and synthesizing sources

Using sources to support your argument

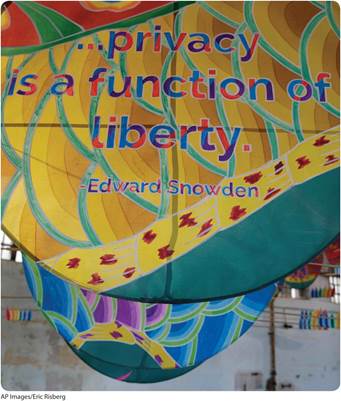

This installation on Alcatraz Island from artist Ai Weiwei features a quotation from Edward Snowden, who became a notorious figure after leaking classified information about potentially privacy-invading surveillance programs to the public.

AT ISSUE

Is Technology a Serious Threat to Our Privacy? (continued)

In Chapter 8, you learned how to evaluate sources for an essay about the dangers of posting personal information online. In this chapter, you will learn how to take notes from sources that address this issue.

As you saw in Chapter 8, before you can decide what material to use to support your arguments, you need to evaluate a variety of potential sources. After you decide which sources you will use, you can begin thinking about where you might use each source. Then, you will need to consider how to integrate information from the sources you have chosen into your essay in the form of summary, paraphrase, and quotation. When you actually write your argument, you will synthesize source material into your essay, blending information from your sources with your own ideas and interpretations (as the student writer did when she wrote the MLA research paper in Chapter 10).

Summarizing Sources

A summary restates the main idea of a passage (or even of an entire book or article) in concise terms. Because a summary does not include the examples or explanations in the source, and because it omits the original source’s rhetorical strategies and stylistic devices, it is always much shorter than the original. Usually, in fact, it consists of just a sentence or two.

WHEN TO SUMMARIZE

Summarize when you want to give readers a general sense of a passage’s main idea or a source’s position on an issue.

When you summarize information, you do not include your own opinions, but you do use your own words and phrasing, not those of your source. If you want to use a particularly distinctive word or phrase from your source, you may do so—but you must always place such words in quotation marks and document them. If you do not, you will be committing plagiarism. (See Chapter 10 for information on documenting sources; see Chapter 11 for information on avoiding plagiarism by using sources responsibly.)

The following paragraph appeared in a newspaper opinion essay.

ORIGINAL SOURCE

When everyone has a blog, a MySpace page, or Facebook entry, everyone is a publisher. When everyone has a cellphone with a camera in it, everyone is a paparazzo. When everyone can upload video on YouTube, everyone is a filmmaker. When everyone is a publisher, paparazzo, or filmmaker, everyone else is a public figure. We’re all public figures now. The blogosphere has made the global discussion so much richer—and each of us so much more transparent. (“The Whole World Is Watching,” Thomas L. Friedman, New York Times, June 27, 2007, p. 23)

The following effective summary conveys a general but accurate sense of the original paragraph without using the source’s phrasing or including the writer’s own opinions. (One distinctive and hard-to-reword phrase is placed in quotation marks.) Parenthetical documentation identifies the source of the material.

EFFECTIVE SUMMARY

The popularity of blogs, social-networking sites, cell phone cameras, and YouTube has enhanced the “global discussion” but made it very hard for people to remain anonymous (Friedman 23).

Notice that this one-sentence summary is much shorter than the original passage and that it does not include all the original’s examples. Still, it accurately communicates a general sense of the original paragraph’s main idea.

The following summary is not acceptable. Not only does it express the student writer’s opinion, but it also uses the source’s exact words without putting them in quotation marks or providing documentation. (This constitutes plagiarism.)

UNACCEPTABLE SUMMARY

It seems to me that nowadays blogs, social-networking sites, cell phone cameras, and YouTube are everywhere, and what this means is that we’re all public figures now.

SUMMARIZING SOURCES

Do

§ Convey the main idea of the original passage.

§ Be concise.

§ Use your own original words and phrasing.

§ Place any distinctive words borrowed from your source in quotation marks.

§ Include documentation.

Do not

§ Include your own analysis or opinions.

§ Include digressions.

§ Argue with your source.

§ Use your source’s syntax or phrasing (unless you are quoting).

![]()

EXERCISE 9.1 WRITING A SUMMARY

Write a two-sentence summary of the following passage. Then, edit your summary so that it is only one sentence long. Be sure your summary conveys the main idea of the original passage and includes proper documentation (see Chapter 10).

Make sure you represent your best self on any social network. On LinkedIn, that means crafting a professional persona. On Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, and Twitter, even if you’re mainly interacting with friends, don’t forget that posts may still be public.

According to a CareerBuilder.com survey, 60 percent of employers research job candidates on social media, and over half are reluctant to hire candidates with no online presence. They’re mainly looking for professionalism, whether you’re a fit for the company and proof of qualifications. If your social media profiles show you in that light, you’re golden. (Alice Underwood, “9 Things to Avoid on Social Media While Looking for a New Job,” Glassdoor, 3 Jan., 2018)

Paraphrasing Sources

A paraphrase is different from a summary. While a summary gives a general overview of the original, a paraphrase presents the source’s ideas in detail, including its main idea, its key supporting points, and perhaps even its examples. For this reason, a paraphrase is longer than a summary. (In fact, it may be as long as the original.)

WHEN TO PARAPHRASE

Paraphrase when you want to communicate the key points discussed in a source—particularly a complex or complicated passage—in clear, accessible language.

Like a summary, a paraphrase uses your own words and phrasing, not the language and syntax of the original. Any distinctive words or phrases from your source must be placed in quotation marks. When you paraphrase, you may not always follow the order of the original source’s ideas, but you should try to convey the writer’s emphasis and most important points.

The following paragraph is from an editorial that appeared in a student newspaper.

ORIGINAL SOURCE

Additionally, as graduates retain their Facebook accounts, employers are increasingly able to use Facebook as an evaluation tool when making hiring decisions. Just as companies sometimes incorporate social functions into their interview process to see if potential hires can handle themselves responsibly, they may also check out a student’s Facebook account to see how the student chooses to present him or herself. This may seem shady and underhanded, but one must understand that social networks are not anonymous; whatever one chooses to post will be available to all. Even if someone goes to great pains to keep an employer-friendly profile, his or her friends may still tag pictures of him or her which will be available to whoever wants to see them. Not only can unexpected Facebook members get information by viewing one’s profile, but a user’s personal information can also leak out by merely registering for the service. Both the user agreement and the privacy policy indicate that Facebook can give information to third parties and can supplement its data with information from newspapers, blogs, and instant messages. (“Beware What You Post on Facebook,” The Tiger, Clemson University, August 4, 2006)

The following paraphrase reflects the original paragraph’s emphasis and clearly communicates its key points.

EFFECTIVE PARAPHRASE

As an editorial in The Tiger observes, because students keep their accounts at social-networking sites after they graduate, potential employers can use the information they find there to help them evaluate candidates’ qualifications. This process is comparable to the way a company might evaluate an applicant in person in a social situation. Some people may see the practice of employers checking applicants’ Facebook pages as “shady and underhanded,” but these sites are not intended to be anonymous or private. For example, a person may try to maintain a profile that will be appropriate for employers, but friends may post inappropriate pictures. Also, people can reveal personal information not only in profiles but also simply by registering with Facebook. Finally, as Facebook states in its membership information, it can supply information to others as well as provide data from other sources. (“Beware”)

Notice that this paraphrase includes many of the details presented in the original passage and quotes a distinctive phrase, but its style and sentence structure are different from those of the original.

The following paraphrase is not acceptable because its phrasing and sentence structure are too close to the original. It also borrows words and phrases from the source without attribution and does not include documentation.

UNACCEPTABLE PARAPHRASE

As more and more college graduates keep their Facebook accounts, employers are increasingly able to use them as evaluation tools when they decide whom to hire. Companies sometimes set up social functions during the interview process to see how potential hires handle themselves; in the same way, they can consult a Facebook page to see how an applicant presents himself or herself. This may seem underhanded, but after all, Facebook is not anonymous; its information is available to all. Many people try to keep their profiles employer friendly, but their friends sometimes tag pictures of them that employers will be able to see. Besides, students’ personal information is available not just on their profiles but also in the form they fill out when they register. Finally, according to their user agreement and their privacy policy, Facebook can give information to third parties and also add data from other sources.

PARAPHRASING SOURCES

Do

§ Convey the source’s ideas fully and accurately.

§ Use your own words and phrasing.

§ Convey the emphasis of the original.

§ Simplify and clarify complex language and syntax.

§ Put any distinctive words borrowed from the source in quotation marks.

§ Include documentation.

Do not

§ Use the exact words or phrasing of your source (unless you are quoting).

§ Include your own analysis or opinions.

§ Argue with or contradict your source.

§ Wander from the topic of the source.

![]()

EXERCISE 9.2 COMPARING SUMMARY AND PARAPHRASE

Write a paraphrase of the passage you summarized in Exercise 9.1. How is your paraphrase different from your summary?

![]()

EXERCISE 9.3 WRITING A PARAPHRASE

The following paragraph is from the same Clemson University student newspaper article that was excerpted on pages 316—17. Read the paragraph, and then write a paraphrase that communicates its key ideas. Before you begin, circle any distinctive words and phrases that might be difficult to paraphrase, and consider whether you should quote them. Be sure to include documentation. (See Chapter 10.)

All these factors make clear the importance of two principles: Responsibility and caveat emptor. First, people should be responsible about how they portray themselves and their friends, and employers, authorities, and the owners must approach this information responsibly and fairly. Second, “let the buyer beware” applies to all parties involved. Facebook users need to understand the potential consequences of the information they share, and outside viewers need to understand that the material on Facebook is often only a humorous, lighthearted presentation of one aspect of a person. Facebook is an incredibly valuable communications tool that will link the college generation more tightly than any before it, but users have to understand that, like anything good in life, they have to be aware of the downsides.

Quoting Sources

When you quote words from a source, you need to quote accurately—that is, every word and every punctuation mark in your quotation must match the source exactly. You also need to be sure that your quotation conveys the meaning its author intended and that you are not distorting the meaning by quoting out of context or by omitting an essential part of the passage you are quoting.

WHEN TO QUOTE

Quote a source’s words only in the following situations:

§ Quote when your source’s words are distinctive or memorable.

§ Quote when your source’s words are so direct and concise that a paraphrase would be awkward or wordy.

§ Quote when your source’s words add authority or credibility to your argument (for example, when your source is a well-known expert on your topic).

§ Quote a point when you will go on to refute it.

Remember, quoting from a source adds interest to your paper—but only when the writer’s words are compelling. Too many quotations—especially long quotations—distract readers and make it difficult for them to follow your discussion. Quote only when you must. If you include too many quotations, your paper will be a patchwork of other people’s words, not an original, unified whole.

QUOTING SOURCES

Do

§ Enclose borrowed words in quotation marks.

§ Quote accurately.

§ Include documentation.

Do not

§ Quote out of context.

§ Distort the source’s meaning.

§ Include too many quotations.

![]()

EXERCISE 9.4 IDENTIFYING MATERIAL TO QUOTE

Read the following paragraphs from a newspaper column. (The full text of this column appears in Exercise 9.5.) If you were going to use these paragraphs as source material for an argumentative essay, which particular words or phrases do you think you might want to quote? Why?

How do users not know that a server somewhere is recording where you are, what you ate for lunch, how often you post photos of your puppy, what you bought at the supermarket for dinner, the route you drove home, and what movie you watched before you went to bed?

So why do we act so surprised and shocked about the invasion of the privacy we so willingly relinquish, and the personal information we forfeit that allows its captors to sell us products, convict us in court, get us fired, or produce more of the same banality that keeps us logging on?

We, all of us, are digital captives. (Shelley Fralic, “Don’t Fall for the Myths about Online Privacy,” Calgary Herald, October 17, 2015.)

![]()

EXERCISE 9.5 SUMMARY AND PARAPHRASE: ADDITIONAL PRACTICE

Read the newspaper column that follows, and highlight it to identify its most important ideas. (For information on highlighting, see Chapter 2.) Then, write a summary of one paragraph and a paraphrase of another paragraph. Assume that this column is a source for an essay you are writing on the topic, “Is Technology a Serious Threat to Our Privacy?” Be sure to include documentation.

DON’T FALL FOR THE MYTHS ABOUT ONLINE PRIVACY

SHELLEY FRALIC

This column is from the Calgary Herald, where it appeared on page 1 on October 17, 2015.

If you are a Facebooker—and there are 1.5 billion of us on the planet, so chances are about one in five that you are—you will have noticed yet another round of posts that suggest in quasi-legalese that you can somehow block the social network’s invasion of your privacy.

This latest hoax cautions that Facebook will now charge $5.99 to keep privacy settings private, and the copyright protection disclaimers making the rounds this week typically begin like this: “As of date-and-time here, I do not give Facebook or any entities associated with Facebook permission to use my pictures, information, or posts, both past and future. By this statement, I give notice to Facebook it is strictly forbidden to disclose, copy, distribute, or take any other action against me based on this profile and/or its contents. The content of this profile is private and confidential information.”

Well, no, it’s not.

This is a new-age version of an old story, oft-told. No one reads the fine print. Not on contracts, not on insurance policies, and not on social media sites that are willingly and globally embraced by perpetually plugged-in gossipmongers, lonely hearts, news junkies, inveterate sharers, and selfie addicts.

Facebook’s fine print, like that of many internet portals, is specific and offers users a variety of self-selected “privacy” options.

But to think that any interaction with it, and its ilk, is truly private is beyond absurd.

How can there still be people out there who still don’t get that Netflix and Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, Google and Tinder, and pretty much every keystroke or communication we register on a smartphone or laptop, not to mention a loyalty card and the GPS in your car, are constantly tracking and sifting and collating everything we do?

How do users not know that a server somewhere is recording where you are, what you ate for lunch, how often you post photos of your puppy, what you bought at the supermarket for dinner, the route you drove home, and what movie you watched before you went to bed?

So why do we act so surprised and shocked about the invasion of the privacy we so willingly relinquish, and the personal information we forfeit that allows its captors to sell us products, convict us in court, get us fired, or produce more of the same banality that keeps us logging on?

We, all of us, are digital captives.

But do we have to be so stupid about it?

“We, all of us, are digital captives.”

And the bigger question is this: If we, the adults who should know better, don’t get it, what are we teaching our kids about the impact and repercussions of their online lives? What are they learning about the voluntary and wholesale abandonment of their privacy? What are we teaching them about “sharing” with strangers?

Worried about future generations not reading books or learning how to spell properly or write in cursive? Worry more, folks, that internet ignorance is the new illiteracy.

Meantime, when another Facebook disclaimer pops up with a plea to share, consider this clever post from a user who actually read the fine print:

“I hereby give my permission to the police, the NSA, the FBI and CIA, the Swiss Guard, the Priory of Scion, the inhabitants of Middle Earth, Agents Mulder and Scully, the Goonies, ALL the Storm Troopers and Darth Vader, the Mad Hatter, Chuck Norris, S.H.I.E.L.D., The Avengers, The Illuminati . . . to view all the amazing and interesting things I publish on Facebook. I’m aware that my privacy ended the very day that I created a profile on Facebook.”

Yes, it did.

Working Source Material into Your Argument

When you use source material in an argumentative essay, your goal is to integrate the material smoothly into your discussion, blending summary, paraphrase, and quotation with your own ideas.

To help readers follow your discussion, you need to indicate the source of each piece of information clearly and distinguish your own ideas from those of your sources. Never simply drop source material into your discussion. Whenever possible, introduce quotations, paraphrases, and summaries with an identifying tag (sometimes called a signal phrase), a phrase that identifies the source, and always follow them with documentation. This practice helps readers identify the boundaries between your own ideas and those of your sources.

It is also important that you include clues to help readers understand why you are using a particular source and what the exact relationship is between your source material and your own ideas. For example, you may be using a source to support a point you are making or to contradict another source.

Using Identifying Tags

Using identifying tags to introduce your summaries, paraphrases, or quotations will help you to accomplish the goals discussed above (and also help you to avoid accidental plagiarism).

SUMMARY WITH IDENTIFYING TAG

According to Thomas L. Friedman, the popularity of blogs, social-networking sites, cell phone cameras, and YouTube has enhanced the “global discussion” but made it hard for people to remain anonymous (23).

Note that you do not always have to place the identifying tag at the beginning of the summarized, paraphrased, or quoted material. You can also place it in the middle or at the end:

IDENTIFYING TAG AT THE BEGINNING

Thomas L. Friedman notes that the popularity of blogs, social-networking sites, cell phone cameras, and YouTube has enhanced the “global discussion” but made it hard for people to remain anonymous (23).

IDENTIFYING TAG IN THE MIDDLE

The popularity of blogs, social-networking sites, cell phone cameras, and YouTube, Thomas L. Friedman observes, has enhanced the “global discussion” but made it hard for people to remain anonymous (23).

IDENTIFYING TAG AT THE END

The popularity of blogs, social-networking sites, cell phone cameras, and YouTube has enhanced the “global discussion” but made it hard for people to remain anonymous, Thomas L. Friedman points out (23).

TEMPLATES FOR USING IDENTIFYING TAGS

To avoid repeating phrases like he says in identifying tags, try using some of the following verbs to introduce your source material. (You can also use “According to . . . ,” to introduce a source.)

For Summaries or Paraphrases

|

[Name of writer] |

notes |

acknowledges |

proposes |

that [summary or paraphrase]. |

|

The writer |

suggests |

believes |

observes |

|

|

The article |

explains |

comments |

warns |

|

|

The essay |

reports |

points out |

predicts |

|

|

implies |

concludes |

states |

For Quotations

|

As [name of writer] |

notes, |

acknowledges, |

proposes, |

“ [quotation] .” |

|

As the writer |

suggests, |

believes, |

observes, |

|

|

As the article |

warns, |

reports, |

points out, |

|

|

As the essay |

predicts, |

implies, |

concludes, |

|

|

states, |

explains, |

Working Quotations into Your Sentences

When you use quotations in your essays, you may need to edit them—for example, by adding, changing, or deleting words—to provide context or to make them fit smoothly into your sentences. If you do edit a quotation, be careful not to distort the source’s meaning.

Adding or Changing Words

When you add or change words in a quotation, use brackets to indicate your edits.

ORIGINAL QUOTATION

“Twitter, Facebook, Flickr, FourSquare, Fitbit, and the SenseCam give us a simple choice: participate or fade into a lonely obscurity” (Cashmore).

WORDS ADDED FOR CLARIFICATION

As Cashmore observes, “Twitter, Flickr, FourSquare, Fitbit, and the SenseCam [as well as similar social-networking sites] give us a simple choice: participate or fade into a lonely obscurity.”

ORIGINAL QUOTATION

“The blogosphere has made the global discussion so much richer—and each of us so much more transparent” (Friedman 23).

WORDS CHANGED TO MAKE VERB TENSE LOGICAL

As Thomas L. Friedman explains, increased access to cell phone cameras, YouTube, and the like continues to “[make] the global discussion so much richer—and each of us so much more transparent” (23).

Deleting Words

When you delete words from a quotation, use ellipses—three spaced periods—to indicate your edits. However, never use ellipses to indicate a deletion at the beginning of a quotation.

ORIGINAL QUOTATION

“Just as companies sometimes incorporate social functions into their interview process to see if potential hires can handle themselves responsibly, they may also check out a student’s Facebook account to see how the student chooses to present him or herself” (“Beware”).

UNNECESSARY WORDS DELETED

“Just as companies sometimes incorporate social functions into their interview process, . . . they may also check out a student’s Facebook account . . .” (“Beware”).

DISTORTING QUOTATIONS

Be careful not to distort a source’s meaning when you add, change, or delete words from a quotation. In the following example, the writer intentionally deletes material from the original quotation that would weaken his argument.

Original Quotation

“This incident is by no means an isolated one. Connecticut authorities are investigating reports that seven girls were sexually assaulted by older men they met online” (“Beware”).

Distorted

“This incident is by no means an isolated one. [In fact,] seven girls were sexually assaulted by older men” they met online (“Beware”).

![]()

EXERCISE 9.6 INTEGRATING QUOTED MATERIAL

Look back at “Don’t Fall for the Myths about Online Privacy” (p. 320). Select three quotations from this essay. Then, integrate each quotation into an original sentence, taking care to place the quoted material in quotation marks. Be sure to acknowledge your source in an identifying tag and to integrate the quoted material smoothly into each sentence.

![]()

EXERCISE 9.7 INTEGRATING SUMMARIES AND PARAPHRASES

Reread the summary you wrote for Exercise 9.1 and the paraphrase you wrote for Exercise 9.3. Add three different identifying tags to each, varying the verbs you use and the position of the tags. Then, check to make sure you have used correct parenthetical documentation. (If the author’s name is included in the identifying tag, it should not also appear in the parenthetical citation.)

Synthesizing Sources

When you write a synthesis, you combine summary, paraphrase, and quotation from several sources with your own ideas to support an original conclusion. You use a synthesis to identify similarities and differences among ideas, indicating where sources agree and disagree and how they support or challenge one another’s ideas. In a synthesis, transitional words and phrases should identify points of similarity (also, like, similarly, and so on) or difference (however, in contrast, and so on). Identifying tags and parenthetical documentation should identify each piece of information from a source and distinguish your sources’ ideas from one another and from your own ideas.

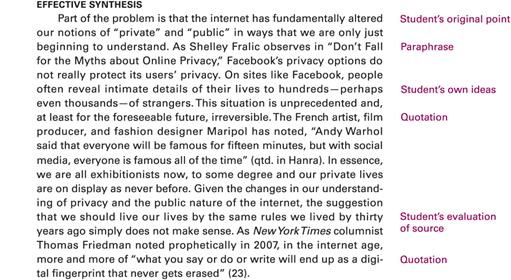

The following effective synthesis is excerpted from the student paper in Chapter 10. Note how the synthesis blends information from three sources with the student’s own ideas to support her point about how the internet has affected people’s concepts of “public” and “private.”

Heading reads, Effective Synthesis. Text reads as follows:

Part of the problem is that the internet has fundamentally altered our notions of “private” and “public” in ways that we are only just beginning to understand (A corresponding margin note reads, Student’s original point). As Shelley Fralic observes in “Don’t Fall for the Myths about Online Privacy,” Facebook’s privacy options do not really protect its users’ privacy (a corresponding margin note reads, Paraphrase). On sites like Facebook, people often reveal intimate details of their lives to hundreds—perhaps even thousands— of strangers (a corresponding margin note reads, Student’s own ideas). This situation is unprecedented and, at least for the foreseeable future, irreversible. The French artist, film producer, and fashion designer Maripol has noted, “Andy Warhol said that everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes, but with social media, everyone is famous all of the time” (qtd. in Hanra) (a corresponding margin note reads, Quotation). In essence, we are all exhibitionists now, to some degree and our private lives are on display as never before. Given the changes in our understanding of privacy and the public nature of the internet, the suggestion that we should live our lives by the same rules we lived by thirty years ago simply does not make sense (corresponding margin note reads, Student’s evaluation of source). As New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman noted prophetically in 2007, in the internet age, more and more of “what you say or do or write will end up as a digital fingerprint that never gets erased” (23) (a corresponding margin note reads, Quatation).

Compare the effective synthesis above with the following unacceptable synthesis.

UNACCEPTABLE SYNTHESIS

“The sheer volume of personal information that people are publishing online—and the fact that some of it could remain visible permanently—is changing the nature of personal privacy.” On sites like Facebook, people can reveal the most intimate details of their lives to millions of total strangers. This development is unprecedented and, at least for the foreseeable future, irreversible. “When everyone has a blog . . . or Facebook entry, everyone is a publisher. … When everyone is a publisher, paparazzo, or filmmaker, everyone else is a public figure” (Friedman 23). Given the changes in our understanding of privacy and the essentially public nature of the internet, the analogy that David Hall makes in an essay about online behavior and workplace discrimination between an online post and a private conversation seems to be of limited use. In the internet age, more and more of “what you say or do or write will end up as a digital fingerprint that never gets erased.”

Unlike the effective synthesis, the preceding unacceptable synthesis does not begin with a topic sentence that introduces the point the source material in the paragraph will support. Instead, it opens with an out-of-context quotation whose source (an essay by Alison George in New Scientist) is not identified. This quotation could have been paraphrased—its wording is not particularly memorable—and, more important, it should have been accompanied by documentation. (If source information is not provided, the writer is committing plagiarism even if the borrowed material is set in quotation marks.) The second quotation, although it includes parenthetical documentation (Friedman 23), is dropped into the paragraph without an identifying tag; the third quotation, also from the Friedman article, is not documented at all, making it appear to be from Hall. All in all, the paragraph is not a smoothly connected synthesis but a string of unconnected ideas. It does not use sources effectively and responsibly, and it does not cite them appropriately.

SYNTHESIZING SOURCES

Do

§ Combine summary, paraphrase, and quotations from sources with your own ideas.

§ Place borrowed words and phrases in quotation marks.

§ Introduce source material with identifying tags.

§ Document material from your sources.

Do not

§ Drop source material into your synthesis without providing context.

§ String random pieces of information together without supplying transitions to connect them.

§ Cram too many pieces of information into a single paragraph; in most cases, two or three sources per paragraph (plus your own comments) will be sufficient.

![]()

EXERCISE 9.8 WRITING A SYNTHESIS

Write a synthesis that builds on the paraphrase you wrote for Exercise 9.2. Add your own original ideas—examples and opinions—to the paraphrase, and also blend in information from one or two of the other sources that appear in this chapter. Use identifying tags and parenthetical documentation to introduce your sources and to distinguish your own ideas from ideas expressed in your sources.

![]()

EXERCISE 9.9 INTEGRATING VISUAL ARGUMENTS

Suppose you were going to use this chapter’s opening image of the Ai Weiwei art installation (p. 312) as a visual argument in an essay about whether technology poses a threat to our privacy, possibly taking into account the artist’s personal history. Write a paragraph in which you introduce the image, briefly describe it, and explain its relevance to your essay’s topic and how it supports your position.