Practical argument: A text and anthology - Laurie G. Kirszner, Stephen R. Mandell 2019

Strategies for Argument

Strategies for argument

Stasis Theory

Different writing purposes call for different argumentative strategies. One way to determine how to approach a topic is by using a rhetorical tool called stasis theory. The word stasis means “a slowing down” or “stopping.” When you apply stasis theory, you ask questions that isolate a topic in order to determine the issue you will explore in your argument.

§ What is the nature of the problem?

§ What are its causes and its results?

§ Is it a good thing or a bad thing?

§ Is it right or wrong?

§ What should be done?

Once you answer these questions, you can decide how best to approach your topic. For example, suppose you were going to develop an argument about animal testing. The topic “animal testing” is so broad that you couldn’t effectively argue for or against it. Notice how the stasis questions enable you to focus your thinking to develop an effective argument.

§ What is the nature of the problem? You could begin trying to determine exactly what animal testing is. What does it involve? What animals are used, and why? How are they treated? Is animal testing unnecessarily cruel? If these questions inspire interesting ideas, you could write an argument by definition. (See Chapter 12.)

§ What is the cause? What effects are associated with it? At this point, you could move on to consider why animal testing is used and what results it has. Why do scientists use animals as testing subjects? Could computer models achieve the same result? Does animal testing make drugs and cosmetics safer? If questions such as these suggest a promising direction to explore, you could structure your essay as a cause-and-effect argument. (See Chapter 13.)

§ Is it a good thing or a bad thing? Here you might examine the risks and/or benefits of animal testing. Is animal testing better than other kinds of testing? Is animal testing cheaper (or more expensive) than other kinds of testing? If these questions seem promising, you could write an evaluation argument. (See Chapter 14.)

§ Is it right or wrong? Now, consider the moral and ethical issues associated with animal testing. Do animals have rights? Do the benefits of animal testing outweigh the harm it causes? If these questions seem useful, you could write an ethical argument. (See Chapter 15.)

§ What should be done? Finally, you could consider how to solve the problems you have identified. What alternatives are there to animal testing? Which, if any, of these alternatives seem feasible? If these questions seem to be the most productive, you could write a proposal argument. (See Chapter 16.)

As you apply each of the questions above, you critically examine the topic you are considering. Thus, these questions help you to identify the kind of argument you are making and to understand the rhetorical choices you need to make in order to develop that argument.

CHAPTER 12 Definition arguments

The text below the photo reads, Paid for by Committee to defend the President. Not Authorized by any candidate or candidate’s committee. www.commiteetodefendthepresident.com Re-elect President Trump. Visit Askcdp.com. Several other billboards are also present in the background.

AT ISSUE

Why Do We Need to Define Fake News?

We currently have access to more information now than at any time in human history. But this endless data stream—from Twitter notifications to Facebook posts—threatens to overwhelm us. Moreover, a good deal of this information is false. Certain misinformation can be relatively harmless, such as urban legends. But other types of information can be harmful, such as unsupported claims about the dangers of childhood vaccinations.

The 2016 election highlighted this problem when factually inaccurate stories and malicious rumors circulated endlessly on the internet. Sometimes these false stories appeared on social media sites or on fake news websites. Occasionally, they made their way into legitimate news outlets. A number of studies have found that many people cannot not tell the difference between what news is false and what news is real. Sites like Snopes.com and factcheck.org have tried to remedy this situation, but they can only verify a small portion of what appears in print and on the internet. Both Facebook and Instagram have tried to screen posts, but they too have found if virtually impossible to identify the overwhelming amount of false information that appears on their sites. Some critics point out that given our country’s robust commitment to free speech, little can or should be done to address this issue. Others question if is appropriate for social media companies to monitor and possibly censor content—especially political content. Even so, the problem remains serious. Fake news can create confusion about what news is real and what news is false. At best, this problem can be frustrating; at worst it can undermine people’s ability to understand important social and political issues.

Later in this chapter, you will be asked to think more about this issue. You will be given several sources to consider and write an argument by definition that takes a position on the issue of misinformation.

What Is a Definition Argument?

When your argument depends on the meaning of a key term or concept, it makes sense to structure your essay as a definition argument. In this type of essay, you will argue that something fits (or does not fit) the definition of a particular class of items. For example, to argue that Facebook’s News Feed is a legitimate research source, you would have to define legitimate research source and show that Facebook’s News Feed fits this definition.

Many arguments focus on definition. In fact, you encounter them so often that you probably do not recognize them for what they are. For example, consider the following questions:

§ Is spanking child abuse?

§ Should offensive speech be banned on campus?

§ Should the rich pay more taxes than others?

§ Are electric cars harmful to the environment?

§ Is cheerleading a sport?

§ Why do we need to define fake news?

You cannot answer these questions without providing definitions. In fact, if you were writing an argumentative essay in response to one of these questions, much of your essay would be devoted to defining and discussing a key term.

QUESTION |

KEY TERM TO BE DEFINED |

Is spanking child abuse? |

child abuse |

Should offensive speech be banned on campus? |

offensive speech |

Should the rich pay more taxes than others? |

rich |

Are electric cars harmful to the environment? |

harmful |

Is cheerleading a sport? |

sport |

Why do we need to define fake news? |

fake news |

Many contemporary social and legal disputes involve definition arguments. For example, did a coworker’s actions constitute sexual harassment? Is an individual trying to enter the United States as an undocumented worker or an illegal alien? Is a person guilty of murder or of manslaughter? Did the CIA engage in torture or in aggressive questioning? Was the magazine cover satirical or racist? Is the punishment just, or is it cruel and unusual? The answers to these and many other questions hinge on definitions of key terms.

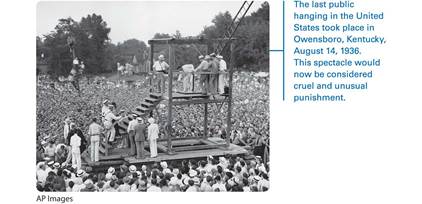

Keep in mind, however, that definitions can change as our thinking about certain issues changes. For example, fifty years ago the word family generally referred to one or more children living with two heterosexual married parents. Now, the term can refer to a wide variety of situations—children living with single parents, gay and lesbian couples, and unmarried heterosexual couples, for example. Our definition of what constitutes cruel and unusual punishment has also changed. Public hanging, a common method of execution for hundreds of years, is now considered barbaric.

Developing Definitions

Definitions explain terms that are unfamiliar to an audience. To make your definitions as clear as possible, avoid making them too narrow, too broad, or circular.

A definition that is too narrow leaves out information that is necessary for understanding a particular word or term. For example, if you define an apple as “a red fruit,” your definition is too narrow since some apples are not red. To be accurate (and useful), your definition needs to be more inclusive and acknowledge the fact that apples can be red, green, or yellow: “An apple is the round edible fruit of a tree of the rose family, which typically has thin red, yellow, or green skin.”

A definition that is too broad includes things that should not be part of the definition. If, for example, you define chair as “something that people sit on,” your definition includes things that are not chairs—stools, park benches, and even tree stumps. To be accurate, your definition needs to be much more specific: “A chair is a piece of furniture that has a seat, legs, arms, and a back and is designed to accommodate one person.”

A circular definition includes the word being defined as part of the definition. For example, if you define patriotism as “the quality of being patriotic,” your definition is circular. For the definition to work, you have to provide new information that enables readers to understand the term: “Patriotism is a belief characterized by love and support for one’s country, especially its values and beliefs.”

NOTE

Sometimes you can clarify a definition by explaining how one term is different from another similar term. For example, consider the following definition:

Patriotism is different from nationalism because patriotism focuses on love for a country while nationalism assumes the superiority of one country over another.

The success of a definition argument depends on your ability to define a term or concept so that readers (even those who do not agree with your position) will see its validity. For this reason, the rhetorical strategies you use to develop your definitions are important.

Dictionary Definitions (Formal Definitions)

When most people think of definitions, they think of the formal definitions they find in a dictionary. Typically, a formal dictionary definition has three parts: the term to be defined, the general class to which the term belongs, and the qualities that differentiate the term from other items in the same class.

TERM |

CLASS |

DIFFERENTIATION |

dog |

a domesticated mammal |

that has a snout, a keen sense of smell, and a barking voice |

naturalism |

a literary movement |

whose followers believed that writers should treat their characters’ lives with scientific objectivity |

![]()

EXERCISE 12.1 WRITING FORMAL DEFINITIONS

Write a one-sentence formal definition of each of the following words. Then, look each word up in a dictionary, and compare your definitions to the ones you found there.

|

Argument |

Respect |

|

App |

Blog |

|

Tablet |

Fairness |

Extended Definitions

Although a definition argument may include a short dictionary definition, a brief definition is usually not enough to define a complex or abstract term. For example, if you were arguing that fake news is a danger to society, you would have to include an extended definition, explaining to readers in some detail what you mean by fake news and perhaps giving some examples that fit your definition.

Examples are often used to develop an extended definition in an argumentative essay. For instance, you could give examples to make the case that a particular baseball player, despite his struggles with substance abuse, is a great athlete. You could define great athlete solely in terms of athletic prowess, presenting several examples of other talented athletes and then showing that the baseball player you are discussing possesses the same qualities.

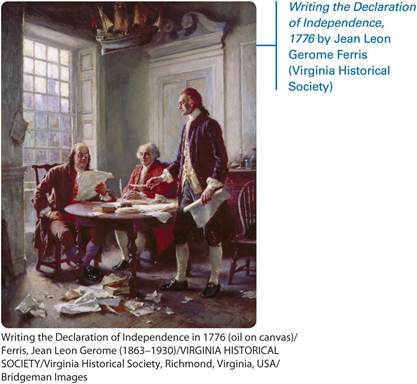

For your examples to be effective, they have to be relevant to your argument. Your examples also have to represent (or at least suggest) the full range of opinion concerning your subject. Finally, you have to make sure that your readers will accept your examples as typical, not unusual. For example, in the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson presented twenty-five paragraphs of examples to support his extended definition of the king’s tyranny. With these examples, he hoped to convince the world that the colonists were justified in breaking away from England. To accomplish his goal, Jefferson made sure that his examples supported his position, that they represented the full range of abuses, and that they were not unusual or atypical.

The painting shows Benjamin Franklin seated in front of a window, with his glasses on, reading the document, John Adams seated beside him and Thomas Jefferson standing, with a parchment in his left hand and a quill in his right hand. The round table in front of them is covered with parchments and the floor beside the table is littered with crumpled papers and books.

![]()

EXERCISE 12.2 DEFINING A TERM

Choose one of the terms you defined in Exercise 12.1, and write a paragraph-length definition argument that takes a position related to that term. Make sure you include two or three examples in your definition.

Operational Definitions

Whereas a dictionary definition tells what a term means, an operational definition defines something by telling how it acts or how it works in a particular set of circumstances. Thus, an operational definition transforms an abstract concept into something concrete, observable, and possibly measurable. Children instinctively understand the concept of operational definitions. When a parent tells them to behave, they know what the components of this operational definition are: clean up your room, obey your parents, come home on time, and do your homework. Researchers in the natural and social sciences must constantly come up with operational definitions. For example, if they want to study the effects of childhood obesity, they have to construct an operational definition of obese. Without such a definition, they will not be able to measure the various factors that make a person obese. For example, at what point does a child become obese? Does he or she have to be 10 percent above normal weight? More? Before researchers can carry out their study, they must agree on an operational (or working) definition.

Structuring a Definition Argument

In general terms, a definition argument can be structured as follows:

§ Introduction: Establishes a context for the argument by explaining the need for defining the term; presents the essay’s thesis

§ Evidence (first point in support of thesis): Provides a short definition of the term as well as an extended definition (if necessary)

§ Evidence (second point in support of thesis): Shows how the term does or does not fit the definition

§ Refutation of opposing arguments: Addresses questions about or objections to the definition; considers and rejects other possible meanings (if any)

§ Conclusion: Reinforces the main point of the argument; includes a strong concluding statement

WHY I AM A NONTRADITIONAL STUDENT

ADAM KENNEDY

![]() The following student essay includes all the elements of a definition argument. The student who wrote this essay is trying to convince his university that he is a nontraditional student and is therefore entitled to the benefits such students receive.

The following student essay includes all the elements of a definition argument. The student who wrote this essay is trying to convince his university that he is a nontraditional student and is therefore entitled to the benefits such students receive.

Text reads as follows:

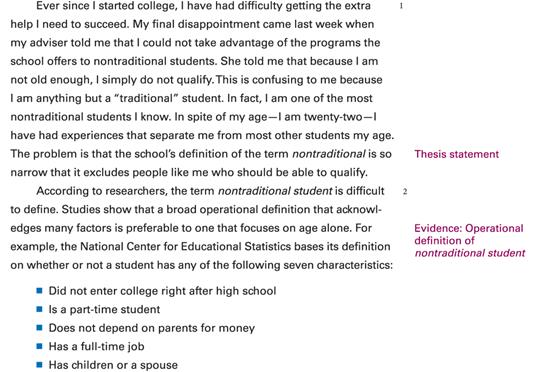

First paragraph: Ever since I started college, I have had difficulty getting the extra help I need to succeed. My final disappointment came last week when my adviser told me that I could not take advantage of the programs the school offers to nontraditional students. She told me that because I am not old enough, I simply do not qualify. This is confusing to me because I am anything but a “traditional” student. In fact, I am one of the most nontraditional students I know. In spite of my age—I am twenty-two—I have had experiences that separate me from most other students my age. The problem is that the school’s definition of the term nontraditional is so narrow that it excludes people like me who should be able to qualify (corresponding margin note reads, Thesis statement).

Second paragraph: According to researchers, the term nontraditional student is difficult to define. Studies show that a broad operational definition that acknowledges many factors is preferable to one that focuses on age alone. For example, the National Center for Educational Statistics bases its definition on whether or not a student has any of the following seven characteristics (corresponding margin note reads, Evidence: Operational definition of nontraditional student):

Did not enter college right after high school

Is a part-time student

Does not depend on parents for money

Has a full-time job

Has children or a spouse

Text continues as follows:

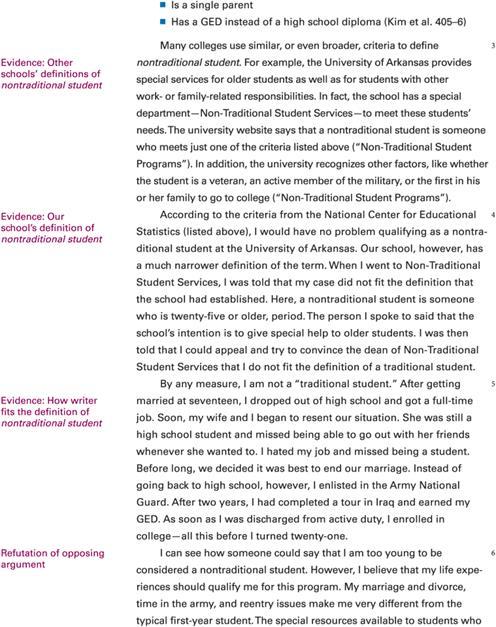

Is a single parent

Has a GED instead of a high school diploma (Kim et al. 405—6)

Third paragraph: Many colleges use similar, or even broader, criteria to define nontraditional student. For example, the University of Arkansas provides special services for older students as well as for students with other work- or family-reLATed responsibilities. In fact, the school has a special department— Non-Traditional Student Services—to meet these students’ needs. The university website says that a nontraditional student is someone who meets just one of the criteria listed above (“Non-Traditional Student Programs”). In addition, the university recognizes other factors, like whether the student is a veteran, an active member of the military, or the first in his or her family to go to college (“Non-Traditional Student Programs”). (A margin note corresponding to the paragraph reads, Evidence: Other schools’ definitions of nontraditional student.)

Fourth paragraph: According to the criteria from the National Center for Educational Statistics (listed above), I would have no problem qualifying as a nontraditional student at the University of Arkansas. Our school, however, has a much narrower definition of the term. When I went to Non-Traditional Student Services, I was told that my case did not fit the definition that the school had established. Here, a nontraditional student is someone who is twenty-five or older, period. The person I spoke to said that the school’s intention is to give special help to older students. I was then told that I could appeal and try to convince the dean of Non-Traditional Student Services that I do not fit the definition of a traditional student. (A margin note corresponding to the paragraph reads, Evidence: Our school’s definition of nontraditional student.)

Fifth paragraph: By any measure, I am not a “traditional student.” After getting married at seventeen, I dropped out of high school and got a full-time job. Soon, my wife and I began to resent our situation. She was still a high school student and missed being able to go out with her friends whenever she wanted to. I hated my job and missed being a student. Before long, we decided it was best to end our marriage. Instead of going back to high school, however, I enlisted in the Army National Guard. After two years, I had completed a tour in Iraq and earned my GED. As soon as I was discharged from active duty, I enrolled in college—all this before I turned twenty-one. (A corresponding margin note reads Evidence: How writer fits the definition of nontraditional student.)

Sixth paragraph: I can see how someone could say that I am too young to be considered a nontraditional student. However, I believe that my life experiences should qualify me for this program. My marriage and divorce, time in the army, and reentry issues make me very different from the typical first-year student. The special resources available to students who (text continues on the next page and a margin note corresponding to the paragraph reads, Refutation of opposing argument).

Sixth paragraph continues as follows:

qualify for this program—tutors, financial aid, special advising, support groups, and subsidized housing—would make my adjustment to college a lot easier. I am only four years older than the average first-year students, but I am nothing like them. The focus on age to define nontraditional ignores the fact that students younger than twenty-five may have followed unconventional paths to college. Life experience, not age, should be the main factor in determining whether a student is nontraditional.

Seventh paragraph: The university should expand the definition of nontraditional to include younger students who have followed unconventional career paths and have postponed college. Even though these students may be younger than twenty-five, they face challenges similar to those faced by older students. Students like me are returning to school in increasing numbers. Our situation is different from that of others our age, and that is exactly why we need all the help we can get (a corresponding margin note reads, Concluding statement).

Works Cited

Kim, Karen A., et al. “Redefining Nontraditional Students: Exploring the

Self-Perceptions of Community College Students.” Community

College Journal of Research and Practice, vol. 34, 2009—10, pp. 402—22.

Academic Search Complete, web.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.bpl.org/.

“Non-Traditional Student Programs.” Office of Campus Life. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2018, ualr.edu/campuslife/ntsp/.

GRAMMAR IN CONTEXT

Avoiding Is Where and Is When

In a formal definition, you may find yourself using the phrase is where or is when. If so, your definition is incomplete because it omits the term’s class. The use of is where or is when signals that you are giving an example of the term, not a definition. You can avoid this problem by making sure that the verb be in your definition is always followed by a noun.

INCORRECT

The university website says that a nontraditional student is when you live off campus, commute from home, have children, are a veteran, or are over the age of twenty-five.

CORRECT

The university website says that a nontraditional student is someone who lives off campus, commutes from home, has children, is a veteran, or is over the age of twenty-five.

![]()

EXERCISE 12.3 ANALYZING THE ELEMENTS OF A DEFINITION ARGUMENT

The following essay, “Athlete vs. Role Model” by Ej Garr, includes the basic elements of a definition argument. Read the essay, and then answer the questions that follow it, consulting the outline on pages 398—399 if necessary.

ATHLETE VS. ROLE MODEL

EJ GARR

This blog post first appeared on August 31, 2014, in the Lifestyle section of newshub.com.

Expectations of professional athletes have become such a touchy subject over the years, and deciphering what defines a role model has become an even darker subject.

Kids who are into sports tend to look up to a favorite player or team and find someone they say they want to be like when they grow up. Unfortunately, athletes today are not what they were decades ago when a paycheck was not the sole reason they wanted an athletic career.

Take Roger Staubach or Bart Starr for example. Both have multiple Super Bowl titles. Both had tremendous NFL careers, and both conducted themselves in public with class and dignity. They deserved every accolade they received, both personally and professionally. Starr and his wife co-founded the Rawhide Boys Ranch, which helps kids who are in need of proper direction and might not have the family resources that can make a kid’s life easier.

Roger Staubach was a class act, served in our Navy, and is a Vietnam vet. These are just two examples of players who gained role model status because of how they acted and what they contributed, not simply because they played in the NFL, and earned a big paycheck. People rooted for them and looked up to them. Kids wanted to be like them. There were absolutely no discouraging words said about them from anyone who has ever met them. They had class, caring, and concern for other people, both on the field and off.

It is easy for kids, who hear about their favorite athlete who signed a multimillion dollar contract, to say to themselves, “I wish I could do that.” Do what? Become a pro or make lots of money? What about becoming a better person? What about giving back?

Many athletes do not think about how to be a better role model to those kids that look up to them, how to make their community better, or what they can “give back” to the less fortunate.

Think back to Pete Rose, who was an amazing ballplayer when he was on the field, but all he is known for today is gambling when he became a manager and being banned for life from baseball and the Hall of Fame. Pete Rose was a role model for every kid in his generation when he played baseball. Ran hard to first on a simple walk and gave every ounce of his being to the game. Then, that all went out the window and the role model moniker was gone faster than you could shake your head at what he did. He didn’t think of those kids who looked up to him.

Then there’s Ray Rice, who was on the cusp of being a role model with a Super Bowl trophy in tow with the Baltimore Ravens. Kids looked up to him. Instead, he was caught on video dragging his unconscious wife out of an elevator after she “accidentally” put her face in front of his fist.

And who can ever forget Michael Vick, who went to prison on dog fighting charges and arranging a death sentence for animals. It has been documented that he even placed a bet or two on those fights! Just recently, although not as criminally serious, USC’s Josh Shaw lied about an injury that he claimed to receive when he rescued his nephew. He finally admitted he fabricated the story and all the facts are not out yet, but he went from a potential role model to a hero and then to a zero in record time. These guys sure aren’t thinking about the kids who look up to them and want to be like them.

These days, sports newscasts are chock-filled with reports of pro athletes using performance enhancing drugs. Over the years there’s been Lance Armstrong, Alex Rodriguez, José Canseco, Shawne Merriman, Barry Bonds, and even gold medalist Marion Jones. It is well documented that Alex Rodriguez spent a lot of money buying performance enhancing drugs, rather than becoming a hardworking baseball player and using his money for good. Alex Rodriguez is only worried about Alex Rodriguez. That, unfortunately, is the ego that many athletes have today. I am me, you are you, and I can do what I want. And who cares if you’re watching what I’m doing and looking up to me.

No sir! Athletes like this are arrogant and act like idiots, carrying guns, hitting spouses, and taking drugs which are all, by the way . . . ILLEGAL in this country! Our world needs more role models like Staubach and Starr and less arrogant athletes who think society owes them something simply because they make big money and live in a big house and drive a nice car.

Professional athletes are not born role models. They are getting paid to play a game. That far from constitutes the making of a role model. Perhaps this mentality of being better than anyone else starts at the college level. Even the NCAA [National Collegiate Athletic Association] has acknowledged that bringing in athletes to fill the stands is more important than making sure they get a quality education, because 75 percent of the athletes who play in college basketball or football are simply there to play their two years and move on to collect a big fat paycheck in the pros. Are they taught anything about giving back and setting a positive example?

“Will that make kids look up to you?”

A role model comes not from being an athlete and collecting that big paycheck, but for what you do with and in your life. Throw a football and score three touchdowns today? Hey, good for you man. You will make the headlines, be highlighted on ESPN, and the press will come calling. Will that make kids look up to you? Sure it will, you won the game and had a great day, good for you. But you’re not a role model.

Do you know why Derek Jeter, Drew Brees, and Tom Brady are true role models? It’s about how they carry themselves on and off the field. It’s about how Jeter, during his rookie year in 1996, achieved his goal of establishing the Turn 2 Foundation, where he gives back and helps kids who are less fortunate. That is a role model! And Drew Brees is a great family man who gives of his time. Here, let me break it down for you. “Brittany and Drew Brees, and the Brees Dream Foundation, have collectively committed and/or contributed just over $20,000,000 to charitable causes and academic institutions in the New Orleans, San Diego, and West Lafayette/Purdue communities.”1

He didn’t buy his way into being a role model. He simply cares about the people who he knows have supported him in his career.

Tom Brady has a beautiful supermodel wife and many guys are saying, “I wish I was Tom Brady so I could be married to a supermodel and win Super Bowls.” That doesn’t make him a role model. It’s because he is a class act who does a ton for the Boys and Girls Clubs of America and gives his time and money to help others.

I have the pleasure of hosting a radio show called Sports Palooza Radio on Blogtalkradio. My wife and I interview professional athletes every Thursday on our two-hour show. Do you know what one of the biggest things is that we look for when we are booking guests? It’s what the athlete does to make someone else’s life a bit easier. Not everyone has it easy and gets spoon-fed money and material things in life. That’s who kids should be looking up to.

There are former NFLers Dennis McKinnon and Lem Barney, who work tirelessly with Gridiron Greats to help former football players. There’s former New York Mets Ed Hearn, who is fighting his own health battle, but works with the NephCure Foundation and his own Bottom of the 9th Foundation. There’s Roy Smalley, who is president of the Pitch in for Baseball foundation, an organization that collects baseball gear for children who don’t have access to others. NFLer Calais Campbell has his own foundation and works hard to help others as well. There are so many other positive examples of athletes doing good things, but they aren’t making the headlines. Those athletes are role models.

And then there’s Donald Driver. He didn’t start out as role model material. In his book, Driven, he tells the story of his rough childhood where he sold drugs to make money and carried guns. But he cleaned up his act and became a stellar NFL superstar, carrying himself with class and dignity. He is founder of the Donald Driver Foundation and the recipient of the 2013 AMVETS Humanitarian of the Year. If a kid looks up to him it’s because he shows them how to overcome and persevere. That’s a role model.

Don’t expect the athletes of today to be instant role models. Instantly famous? Maybe that is a better description, but an athlete needs to earn the role model status. That honor is not bestowed on you because you cashed a nice paycheck for playing a game!

Identifying the Elements of a Definition Argument

1. This essay does not include a formal definition of role model. Why not? Following the template below, write your own one-sentence definition of role model.

A role model is a who

2. Throughout this essay, Garr gives examples of athletes who are and who are not role models. What does he accomplish with this strategy?

3. This essay was written in 2014. Do you think that Garr’s thesis holds up? What contemporary athletes would you substitute for the ones Garr discusses?

4. In paragraph 16, Garr discusses why Tom Brady, quarterback for the NFL’s New England Patriots, is a role model. Since this article was written, Brady was accused of deflating footballs during the 2015 Super Bowl to give his team an unfair advantage. Although Brady denied the charges, the NFL gave him a four-game suspension. Does this scandal disqualify him from being a role model? Does Brady’s scandal rise to the level of those involving Pete Rose, Ray Rice, and Michael Vick? Why or why not?

5. Where in the essay does Garr define the term role model by telling what it is not? What does Garr accomplish with this strategy?

6. Where does Garr introduce possible objections to his idea of a role model? Does he refute these objections convincingly? If not, how should he have addressed them?

7. In paragraph 17, Garr says that he and his wife host a radio show. Why does he mention this fact?

![]()

EXERCISE 12.4 WRITING A DEFINITION ARGUMENT

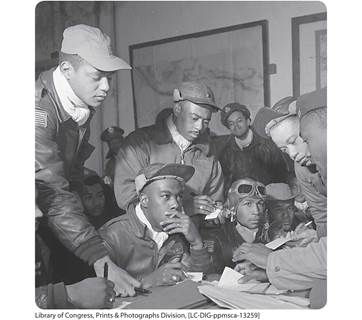

According to former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, “We gain strength, and courage, and confidence by each experience in which we really stop to look fear in the face. . . . We must do that which we think we cannot.” Each of the two pictures that follow presents a visual definition of courage. Study the pictures, and then write a paragraph in which you argue that they are (or are not) consistent with Roosevelt’s concept of courage.

Firefighters at Ground Zero after the World Trade Center terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, in New York City

The Tuskegee Airmen, a group of African-American men who overcame tremendous odds to become U.S. Army pilots during World War II

![]()

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

Why Do We Need to Define Fake News?

The text below the photo reads, Paid for by Committee to defend the President. Not Authorized by any candidate or candidate’s committee. www.commiteetodefendthepresident.com Re-elect President Trump. Visit Askcdp.com. Several other billboards are also present in the background.

Go back to page 393 and reread the At Issue box, which gives some background on the question of why we need to define fake news. As the following sources illustrate, this question suggests a variety of possible responses.

As you read the sources that follow, you will be asked to answer some questions and to complete some simple activities. This work will help you understand both the content and the structure of the sources. When you are finished, you will be ready to write a definition argument on the topic, “Why Do We Need to Define Fake News?”

SOURCES

Joanna M. Burkhardt, “History of Fake News,” page 409 |

Jimmy Wales, “What We Can Do to Combat Fake News,” page 416 |

Adrian Chen, “The Fake News Fallacy,” page 418 |

Katie Langin, “Fake News Spreads Faster Than True News on Twitter,” page 427 |

Kalev Leetaru, “How Data and Information Literacy Could End Fake News,” page 429 |

Visual Argument, page 433 |

HISTORY OF FAKE NEWS

JOANNA M. BURKHARDT

This piece first appeared in the November/December 2017 issue of Library Technology Reports as part of a longer feature on fake news.

“Massive digital misinformation is becoming pervasive in online social media to the extent that it has been listed by the World Economic Forum (WEF) as one of the main threats to our society.”1

Fake news is nothing new. While fake news was in the headlines frequently in the 2016 U.S. election cycle, the origins of fake news date back to before the printing press. Rumor and false stories have probably been around as long as humans have lived in groups where power matters. Until the printing press was invented, news was usually transferred from person to person via word of mouth. The ability to have an impact on what people know is an asset that has been prized for many centuries.

Pre—Printing Press Era

Forms of writing inscribed on materials like stone, clay, and papyrus appeared several thousand years ago. The information in these writings was usually limited to the leaders of the group (emperors, pharaohs, Incas, religious and military leaders, and so on). Controlling information gave some people power over others and has probably contributed to the creation of most of the hierarchical cultures we know today. Knowledge is power. Those controlling knowledge, information, and the means to disseminate information became group leaders, with privileges that others in the group did not have. In many early state societies, remnants of the perks of leadership remain—pyramids, castles, lavish household goods, and more.

Some of the information that has survived, carved in stone or baked on tablets or drawn in pictograms, extolled the wonder and power of the leaders. Often these messages were reminders to the common people that the leader controlled their lives. Others were created to ensure that an individual leader would be remembered for his great prowess, his success in battle, or his great leadership skills. Without means to verify the claims, it’s hard to know whether the information was true or fake news.

In the sixth century AD, Procopius of Caesarea (500—ca. 554 AD), the principal historian of Byzantium, used fake news to smear the Emperor Justinian.2 While Procopius supported Justinian during his lifetime, after the emperor’s death Procopius released a treatise called Secret History that discredited the emperor and his wife. As the emperor was dead, there could be no retaliation, questioning, or investigations. Since the new emperor did not favor Justinian, it is possible the author had a motivation to distance himself from Justinian’s court, using the stories (often wild and unverifiable) to do so.

Post—Printing Press Era

The invention of the printing press and the concurrent spread of literacy made it possible to spread information more widely. Those who were literate could easily use that ability to manipulate information to those who were not literate. As more people became literate, it became more difficult to mislead by misrepresenting what was written.

As literacy rates increased, it eventually became economically feasible to print and sell information. This made the ability to write convincingly and authoritatively on a topic a powerful skill. Leaders have always sought to have talented writers in their employ and to control what information was produced. Printed information became available in different formats and from different sources. Books, newspapers, broadsides, and cartoons were often created by writers who had a monetary incentive. Some were paid by a publisher to provide real news. Others, it seems, were paid to write information for the benefit of their employer.

In 1522, Italian author and satirist Pietro Aretino wrote wicked sonnets, pamphlets, and plays. He self-published his correspondence with the nobility of Italy, using their letters to blackmail former friends and patrons. If those individuals failed to provide the money he required, their indiscretions became public. He took the Roman style of pasquino—anonymous lampooning—to a new level of satire and parody. While his writings were satirical (not unlike today’s Saturday Night Live satire), they planted the seeds of doubt in the minds of their readers about the people in power in Italy and helped to shape the complex political reality of the time.3

Aretino’s pasquinos were followed by a French variety of fake news known as the canard. The French word canard can be used to mean an unfounded rumor or story. Canards were rife during the seventeenth century in France. One canard reported that a monster, captured in Chile, was being shipped to France. This report included an engraving of a dragon-like creature. During the French Revolution the face of Marie Antoinette was superimposed onto the dragon. The revised image was used to disparage the queen.4 The resulting surge in unpopularity for the queen may have contributed to her harsh treatment during the revolution.

Jonathan Swift complained about political fake news in 1710 in his essay “The Art of Political Lying.” He spoke about the damage that lies can do, whether ascribed to a particular author or anonymous: “Falsehood flies, and truth comes limping after it, so that when men come to be undeceived, it is too late; the jest is over, and the tale hath had its effect.”5 Swift’s descriptions of fake news in politics in 1710 are remarkably similar to those of writers of the twentyfirst century.

American writer Edgar Allan Poe in 1844 wrote a hoax newspaper article claiming that a balloonist had crossed the Atlantic in a hot air balloon in only three days.6 His attention to scientific details and the plausibility of the idea caused many people to believe the account until reporters failed to find the balloon or the balloonist. The story was retracted four days after publication. Poe is credited with writing at least six stories that turned out to be fake news.7

Mass Media Era

Father Ronald Arbuthnott Knox did a fake news broadcast in January 1926 called “Broadcasting the Barricades” on BBC radio.8 During this broadcast Knox implied that London was being attacked by Communists, Parliament was under siege, and the Savoy Hotel and Big Ben had been blown up. Those who tuned in late did not hear the disclaimer that the broadcast was a spoof and not an actual news broadcast. This dramatic presentation, coming only a few months after the General Strike in England, caused a minor panic until the story could be explained.

“It is easy to see that fake news has existed for a long time.”

This fake news report was famously followed by Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds broadcast in 1938. The War of the Worlds was published as a book in 1898, but those who did not read science fiction were unfamiliar with the story. The presentation of the story as a radio broadcast again caused a minor panic, this time in the United States, as there were few clues to indicate that reports of a Martian invasion were fictional. While this broadcast was not meant to be fake news, those who missed the introduction didn’t know that.9

On November 3, 1948, the Chicago Daily Tribune editors were so certain of the outcome of the previous day’s presidential election that they published the paper with a headline stating, “Dewey Defeats Truman.” An iconic picture shows President Truman holding up the newspaper with the erroneous headline. The caption for the picture quotes Truman as saying, “That ain’t the way I heard it.”10 The paper, of course, retracted the statement and reprinted the paper with the correct news later in the day. This incident is one reason that journalists at reputable news outlets are required to verify information a number of times before publication.

It is easy to see that fake news has existed for a long time. From the few examples described above, the effects of fake news have ranged widely, from amusement to death. Some authors of fake news probably had benign motivations for producing it. Others appear to have intended to harm individuals, families, or governments. The intended and unintended consequences of fake news of the pre-internet era were profound and far-reaching for the time. As the means of spreading fake news increased, the consequences became increasingly serious.

Internet Era

In the late twentieth century, the internet provided new means for disseminating fake news on a vastly increased scale. When the internet was made publicly available, it was possible for anyone who had a computer to access it. At the same time, innovations in computers made them affordable to the average person. Making information available on the internet became a new way to promote products as well as make information available to everyone almost instantly.

Some fake websites were created in the early years of generalized web use. Some of these hoax websites were satire. Others were meant to mislead or deliberately spread biased or fake news. Early library instruction classes used these types of website as cautionary examples of what an internet user needed to look for. Using a checklist of criteria to identify fake news websites was relatively easy. A few hoax website favorites are

§ DHMO.org. This website claims that the compound DHMO (Dihydrogen Monoxide), a component of just about everything, has been linked to terrible problems such as cancer, acid rain, and global warming. While everything suggested on the website is true, it is not until one’s high school chemistry kicks in that the joke is revealed—DHMO and H2O are the same thing.

§ Feline Reactions to Bearded Men. Another popular piece of fake news is a “research study” regarding the reactions of cats to bearded men. This study is reported as if it had been published in a scientific journal. It includes a literature review, a description of the experiment, the raw data resulting from the experiment, and the conclusions reached by the researchers as a result. It is not until the reader gets to the bibliography of the article that the experiment is revealed to be a hoax. Included in the bibliography are articles supposedly written by Madonna Louise Ciccone (Madonna the singer), A. Schwartzenegger (Arnold, perhaps?), and Doctor Seuss and published in journals such as the Western Musicology Journal, Tonsological Proceedings, and the Journal of Feline Forensic Studies.

§ city-mankato.us. One of the first websites to make use of website technology to mislead and misdirect was a fake site for the city of Mankato, Minnesota. This website describes the climate as temperate to tropical, claiming that a geological anomaly allows the Mankato Valley to enjoy a year-round temperature of no less than 70 degrees Fahrenheit, while providing snow year-round at nearby Mount Kroto. It reported that one could watch the summer migration of whales up the Minnesota River. An insert shows a picture of a beach, with a second insert showing the current temperature—both tropical. The website proudly announces that it is a Yahoo “Pick of the Week” site and has been featured by the New York Times and the Minneapolis Star Tribune. Needless to say, no geological anomaly of this type exists in Minnesota. Whales do not migrate up (or down) the Minnesota River at any time, and the pictures of the beaches and the thermometer are actually showing beaches and temperatures from places very far south of Mankato. It is true that Yahoo, the New York Times, and the Minneapolis Star Tribune featured this website, but not for the reasons you might think. When fake news could still be amusing, this website proved both clever and ironic.

§ MartinLutherKing.org. This website was created by Stormfront, a white supremacist group, to try to mislead readers about the Civil Rights activist by discrediting his work, his writing, and his personal life.11 The fact that the website used the .org domain extension convinced a number of people that it was unbiased because the domain extension was usually associated with nonprofit organizations working for good. The authors of the website did not reveal themselves nor did they state their affiliations. Using Martin Luther King’s name for the website ensured that people looking for information about King could easily arrive at this fake news website. This website is no longer active.

Global Reach of Fake News

Initial forays into the world of fake news fall into the category of entertainment, satire, and parody. They are meant to amuse or to instruct the unwary. Canards and other news that fall into the category of misinformation and misdirection, like the Martin Luther King website, often have more sinister and serious motives. In generations past, newspaper readers were warned that just because something was printed in the newspaper did not mean that it was true. In the twenty-first century, the same could be said about the internet. People of today create fake news for many of the same reasons that people of the past did. A number of new twists help to drive the creation and spread of fake news that did not exist until recently.

Twenty-first-century economic incentives have increased the motivation to supply the public with fake news. The internet is now funded by advertisers rather than by the government. Advertisers are in business to get information about their products to as many people as possible. Advertisers will pay a website owner to allow their advertising to be shown, just as they might pay a newspaper publisher to print advertisements in the paper. How do advertisers decide in which websites to place their ads? Using computing power to collect the data, it is possible to count the number of visits and visitors to individual sites. Popular websites attract large numbers of people who visit those sites, making them attractive to advertisers. The more people who are exposed to the products advertisers want to sell, the more sales are possible. The fee paid to the website owners by the advertisers rewards website owners for publishing popular information and provides an incentive to create more content that will attract more people to the site.

People are attracted to gossip, rumor, scandal, innuendo, and the unlikely. Access Hollywood on TV and the National Enquirer at the newsstand have used human nature to make their products popular. That popularity attracts advertisers. In a Los Angeles Times op-ed, Matthew A. Baum and David Lazer report “Another thing we know is that shocking claims stick in your memory. A long-standing body of research shows that people are more likely to attend to and later recall a sensational or negative headline, even if a fact checker flags it as suspect.”12

In the past several years, people have created websites that capitalize on those nonintellectual aspects of human nature. Advertisers are interested in how many people will potentially be exposed to their products, rather than the truth or falsity of the content of the page on which the advertising appears. Unfortunately, sites with sensational headlines or suggestive content tend to be very popular, generating large numbers of visits to those sites and creating an advertising opportunity. Some advertisers will capitalize on this human propensity for sensation by paying writers of popular content without regard for the actual content at the site. The website can report anything it likes, as long as it attracts a large number of people. This is how fake news is monetized, providing incentives for writers to concentrate on the sensational rather than the truthful.

The problem with most sensational information is that it is not always based on fact, or those facts are twisted in some way to make the story seem like something it is not. It is sometimes based on no information at all. For example:

Creators of fake news found that they could capture so much interest that they could make money off fake news through automated advertising that rewards high traffic to their sites. A man running a string of fake news sites from the Los Angeles suburbs told NPR he made between $10,000 and $30,000 a month. A computer science student in the former Soviet republic of Georgia told the New York Times that creating a new website and filling it with both real stories and fake news that flattered Trump was a “gold mine.”13

Technological advances have increased the spread of information and democratized its consumption globally. There are obvious benefits associated with instantaneous access to information. The dissemination of information allows ideas to be shared and formerly inaccessible regions to be connected. It makes choices available and provides a platform for many points of view.

However, in a largely unregulated medium, supported and driven by advertising, the incentive for good is often outweighed by the incentive to make money, and this has a major impact on how the medium develops over time. Proliferation of fake news is one outcome. While the existence of fake news is not new, the speed at which it travels and the global reach of the technology that can spread it are unprecedented. Fake news exists in the same context as real news on the internet. The problem seems to be distinguishing between what is fake and what is real.

![]()

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A DEFINITION ARGUMENT

1. Where does Burkhardt define fake news? Does she define this term in enough detail? If not, what could she have done to make her definition more understandable?

2. In her essay, Burkhardt applies the term fake news to a treatise written in the sixth century AD and to two radio dramas broadcast in the twentieth century. Is the use of the term in these contexts accurate? Explain.

3. According to Burkhardt, the invention of both the printing press and the internet made it possible to spread information to a great number of people. In what sense are the printing press and the internet alike? How are they different?

4. How, according to Burkhardt, do the economic incentives of the internet increase “the motivation to supply the public with fake news” (para. 18)?

5. Burkhardt’s purpose in writing this essay is mainly to convey information, to give the history of fake news. At what point in the essay does she indicate that she also might be trying to convince her readers of something? What is her thesis?

WHAT WE CAN DO TO COMBAT FAKE NEWS

JIMMY WALES

This piece originally appeared on the website Quora, in answer to a question about how to fight the spread of fake news.

There are (at least) two problems that give rise to the “fake news” phenomenon. But let me pause for a minute first to define how I’m using the term for the purposes of this post.

I’m not talking about biased news, or errors made by major publications, nor even irresponsible publication practices taken by what ought to be responsible publications. We’ll get to that, as you’ll see, but those aren’t themselves “fake news” in the technical sense.

Fake news is “news” put forward fraudulently by people just working the system at publications that aren’t really news organizations. It can either be politically motivated and well-funded (in some cases perhaps by state-level actors) or it can just be spam. This news has catchy headlines and juicy stories but has absolutely zero concern for the truth, nor usually any concern for appearing truthful other than for just long enough to trick some poor sap into sharing it.

“Various problems with traditional media have given rise to a real loss of trust, and this has given rise to plausibility and gullibility.”

What gives rise to that?

First is the “distribution” problem—and this is something that Facebook and Twitter and others are struggling to deal with. I think progress will be made here, just as progress has been made against spam email.

The second issue is the one I’m more interested in. And that’s that various problems with traditional media have given rise to a real loss of trust, and this has given rise to plausibility and gullibility. In short, when we get biased news, frequent errors, clickbait headlines, an extreme race to publish first (whether a story is confirmed or not), then the public doesn’t know who to trust or what counts as real.

What’s the solution to that? At WikiTribune what I’m really putting forward is a strong ethos that we must show our work. If we have an interview, we should, to the maximum degree possible, post the audio and the transcript. If we have quotes from a source, we should to the maximum degree possible, name the person we are quoting. If we have documents, we should, to the maximum degree possible, publish the documents.

Not everyone will read all of that background material, of course. But it will be there for a community of people who are interested in holding truth as a core value to read and to edit our work to improve it, in case someone has gone beyond what the source said, or written in a biased manner, etc.

Now I do want to add that in some cases, that kind of ultimate transparency isn’t possible. Sometimes you do need to protect a whistleblower. But even in those cases, there should be processes and procedures that are transparent and reasonable and verifiable and publicly signed off on to make sure that such things are being done in a responsible way.

If more media outlets take this approach, then the public understanding of what “counts” as real news will shift. Just looking like a newspaper masthead won’t be enough—people will expect to see the source documentation just a click away.

![]()

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A DEFINITION ARGUMENT

1. Wales defines fake news in paragraphs 2 and 3. How does his definition differ from the one Burkhardt includes in her essay? Which definition do you think is more accurate? Explain.

2. In paragraph 5, Wales refers to the “’distribution’ problem.” What do you think he means? What progress has been made against “spam email”?

3. What are the problems associated with traditional media? What is the result of these problems? According to Wales, how is WikiTribune, a Wikipedia-like news site, solving these problems?

4. What assumptions does Wales make about the readers of WikiTribune? Do you think his assumptions are justified? Explain.

5. In paragraph 9, Wales refers to “ultimate transparency.” What does he mean? Why is ultimate transparency not possible in some cases?

6. In an article in the Atlantic about WikiTribune, Adrienne Lawrence says the following:

So it’s tempting to imagine a new kind of journalism site that tidily solves so many of the industry’s problems—a site that’s indifferent to the shrinking pool of available ad dollars, that gets people to carefully vet the information they encounter on a massive scale, a site that inspires people to spend their money on quality journalism, and a site that consistently produces it. This is ambitious stuff. Maybe too ambitious.

o What does Lawrence mean when she says, “This is ambitious stuff. Maybe too ambitious”?

THE FAKE NEWS FALLACY

ADRIAN CHEN

This essay originally appeared in the New Yorker on September 4, 2017.

On the evening of October 30, 1938, a seventy-six-year-old millworker in Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, named Bill Dock heard something terrifying on the radio. Aliens had landed just down the road, a newscaster announced, and were rampaging through the countryside. Dock grabbed his double-barrelled shotgun and went out into the night, prepared to face down the invaders. But, after investigating, as a newspaper later reported, he “didn’t see anybody he thought needed shooting.” In fact, he’d been duped by Orson Welles’s radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds. Structured as a breaking-news report that detailed the invasion in real time, the broadcast adhered faithfully to the conventions of news radio, complete with elaborate sound effects and impersonations of government officials, with only a few brief warnings through the program that it was fiction.

The next day, newspapers were full of stories like Dock’s. “Thirty men and women rushed into the West 123rd Street police station,” ready to evacuate, according to the Times. Two people suffered heart attacks from shock, the Washington Post reported. One caller from Pittsburgh claimed that he had barely prevented his wife from taking her own life by swallowing poison. The panic was the biggest story for weeks; a photograph of Bill Dock and his shotgun, taken the next day, by a Daily News reporter, went “the 1930s equivalent of viral,” A. Brad Schwartz writes in his recent history, Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News.

This early fake-news panic lives on in legend, but Schwartz is the latest of a number of researchers to argue that it wasn’t all it was cracked up to be. As Schwartz tells it, there was no mass hysteria, only small pockets of concern that quickly burned out. He casts doubt on whether Dock had even heard the broadcast. Schwartz argues that newspapers exaggerated the panic to better control the upstart medium of radio, which was becoming the dominant source of breaking news in the thirties. Newspapers wanted to show that radio was irresponsible and needed guidance from its older, more respectable siblings in the print media, such “guidance” mostly taking the form of lucrative licensing deals and increased ownership of local radio stations. Columnists and editorialists weighed in. Soon, the Columbia education professor and broadcaster Lyman Bryson declared that unrestrained radio was “one of the most dangerous elements in modern culture.”

The argument turned on the role of the Federal Communications Commission (F.C.C.), the regulators charged with ensuring that the radio system served the “public interest, convenience, and necessity.” Unlike today’s F.C.C., which is known mainly as a referee for media mergers, the F.C.C. of the thirties was deeply concerned with the particulars of what broadcasters put in listeners’ ears—it had recently issued a reprimand after a racy Mae West sketch that so alarmed NBC it banned West from its stations. To some, the lesson of the panic was that the F.C.C. needed to take an even more active role to protect people from malicious tricksters like Welles. “Programs of that kind are an excellent indication of the inadequacy of our present control over a marvellous facility,” the Iowa senator Clyde Herring, a Democrat, declared. He announced a bill that would require broadcasters to submit shows to the F.C.C. for review before airing. Yet Schwartz says that the people calling for a government crackdown were far outnumbered by those who warned against one. “Far from blaming Mr. Orson Welles, he ought to be given a Congressional medal and a national prize,” the renowned columnist Dorothy Thompson wrote.

Thompson was concerned with a threat far greater than rogue thespians. Everywhere you looked in the thirties, authoritarian leaders were being swept to power with the help of radio. The Nazi Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda deployed a force called the Funkwarte, or Radio Guard, that went block by block to ensure that citizens tuned in to Hitler’s major broadcast speeches, as Tim Wu details in his new book, The Attention Merchants. Meanwhile, homegrown radio demagogues like Father Charles Coughlin and the charismatic Huey Long made some people wonder about a radio-aided Fascist takeover in America. For Thompson, Welles had made an “admirable demonstration” about the power of radio. It showed the danger of handing control of the airwaves over to the state. “No political body must ever, under any circumstances, obtain a monopoly of radio,” she wrote. “The greatest organizers of mass hysterias and the mass delusions today are states using the radio to excite terrors, incite hatreds, inflame masses.”

Donald Trump’s victory has been a demonstration, for many people, of how the internet can be used to achieve those very ends. Trump used Twitter less as a communication device than as a weapon of information warfare, rallying his supporters and attacking opponents with hundred-and-forty-character barrages. “I wouldn’t be here without Twitter,” he declared on Fox News in March. Yet the internet didn’t just give him a megaphone. It also helped him peddle his lies through a profusion of unreliable media sources that undermined the old providers of established fact. Throughout the campaign, fake-news stories, conspiracy theories, and other forms of propaganda were reported to be flooding social networks. The stories were overwhelmingly pro-Trump, and the spread of whoppers like “Pope Francis Shocks World, Endorses Donald Trump for President”—hardly more believable than a Martian invasion—seemed to suggest that huge numbers of Trump supporters were being duped by online lies. This was not the first campaign to be marred by misinformation, of course. But the sheer outlandishness of the claims being made, and believed, suggested to many that the internet had brought about a fundamental devaluing of the truth. Many pundits argued that the “hyper-democratizing” force of the internet had helped usher in a “post-truth” world, where people based their opinions not on facts or reason but on passion and prejudice.

Yet, even among this information anarchy, there remains an authority of sorts. Facebook and Google now define the experience of the internet for most people, and in many ways they play the role of regulators. In the weeks after the election, they faced enormous criticism for their failure to halt the spread of fake news and misinformation on their services. The problem was not simply that people had been able to spread lies but that the digital platforms were set up in ways that made them especially potent. The “share” button sends lies flying around the web faster than fact checkers can debunk them. The supposedly neutral platforms use personalized algorithms to feed us information based on precise data models of our preferences, trapping us in “filter bubbles” that cripple critical thinking and increase polarization. The threat of fake news was compounded by this sense that the role of the press had been ceded to an arcane algorithmic system created by private companies that care only about the bottom line.

Not so very long ago, it was thought that the tension between commercial pressure and the public interest would be one of the many things made obsolete by the internet. In the mid-aughts, during the height of the Web 2.0 boom, the pundit Henry Jenkins declared that the Internet was creating a “participatory culture” where the top-down hegemony of greedy media corporations would be replaced by a horizontal network of amateur “prosumers” engaged in a wonderfully democratic exchange of information in cyberspace—an epistemic agora that would allow the whole globe to come together on a level playing field. Google, Facebook, Twitter, and the rest attained their paradoxical gatekeeper status by positioning themselves as neutral platforms that unlocked the internet’s democratic potential by empowering users. It was on a private platform, Twitter, where pro-democracy protesters organized, and on another private platform, Google, where the knowledge of a million public libraries could be accessed for free. These companies would develop into what the tech guru Jeff Jarvis termed “radically public companies,” which operate more like public utilities than like businesses.

But there has been a growing sense among mostly liberal-minded observers that the platforms’ championing of openness is at odds with the public interest. The image of Arab Spring activists using Twitter to challenge repressive dictators has been replaced, in the public imagination, by that of ISIS propagandists luring vulnerable Western teenagers to Syria via YouTube videos and Facebook chats. The openness that was said to bring about a democratic revolution instead seems to have torn a hole in the social fabric. Today, online misinformation, hate speech, and propaganda are seen as the front line of a reactionary populist upsurge threatening liberal democracy. Once held back by democratic institutions, the bad stuff is now sluicing through a digital breach with the help of irresponsible tech companies. Stanching the torrent of fake news has become a trial by which the digital giants can prove their commitment to democracy. The effort has reignited a debate over the role of mass communication that goes back to the early days of radio.

“The openness that was said to bring about a democratic revolution instead seems to have torn a hole in the social fabric.”

The debate around radio at the time of The War of the Worlds was informed by a similar fall from utopian hopes to dystopian fears. Although radio can seem like an unremarkable medium—audio wallpaper pasted over the most boring parts of your day—the historian David Goodman’s book Radio’s Civic Ambition: American Broadcasting and Democracy in the 1930s makes it clear that the birth of the technology brought about a communications revolution comparable to that of the internet. For the first time, radio allowed a mass audience to experience the same thing simultaneously from the comfort of their homes. Early radio pioneers imagined that this unprecedented blurring of public and private space might become a sort of ethereal forum that would uplift the nation, from the urban slum dweller to the remote Montana rancher. John Dewey called radio “the most powerful instrument of social education the world has ever seen.” Populist reformers demanded that radio be treated as a common carrier and give airtime to anyone who paid a fee. Were this to have come about, it would have been very much like the early online-bulletin-board systems where strangers could come together and leave a message for any passing online wanderer. Instead, in the regulatory struggles of the twenties and thirties, the commercial networks won out.

Corporate networks were supported by advertising, and what many progressives had envisaged as the ideal democratic forum began to seem more like Times Square, cluttered with ads for soap and coffee. Rather than elevating public opinion, advertisers pioneered techniques of manipulating it. Who else might be able to exploit such techniques? Many saw a link between the domestic on-air advertising boom and the rise of Fascist dictators like Hitler abroad. Tim Wu cites the leftist critic Max Lerner, who lamented that “the most damning blow the dictatorships have struck at democracy has been the compliment they have paid us in taking over and perfecting our prized techniques of persuasion and our underlying contempt for the credulity of the masses.”

Amid such concerns, broadcasters were under intense pressure to show that they were not turning listeners into a zombified mass ripe for the Fascist picking. What they developed in response is, in Goodman’s phrase, a “civic paradigm”: radio would create active, rational, tolerant listeners—in other words, the ideal citizens of a democratic society. Classical- music-appreciation shows were developed with an eye toward uplift. Inspired by progressive educators, radio networks hosted “forum” programs, in which citizens from all walks of life were invited to discuss the matters of the day, with the aim of inspiring tolerance and political engagement. One such program, America’s Town Meeting of the Air, featured in its first episode a Communist, a Fascist, a Socialist, and a Democrat.

Listening to the radio, then, would be a “civic practice” that could create a more democratic society by exposing people to diversity. But only if they listened correctly. There was great concern about distracted and gullible listeners being susceptible to propagandists. A group of progressive journalists and thinkers known as “propaganda critics” set about educating radio listeners. The Institute for Propaganda Analysis, co-founded by the social psychologist Clyde R. Miller, with funding from the department-store magnate Edward Filene, was at the forefront of the movement. In newsletters, books, and lectures, the institute’s members urged listeners to attend to their own biases while analyzing broadcast voices for signs of manipulation. Listening to the radio critically became the duty of every responsible citizen. Goodman, who is generally sympathetic to the proponents of the civic paradigm, is alert to the off notes here of snobbery and disdain: much of the progressive concern about listeners’ abilities stemmed from the belief that Americans were, basically, dim-witted—an idea that gained currency after intelligence tests on soldiers during the First World War supposedly revealed discouraging news about the capacities of the average American. In the wake of The War of the Worlds panic, commentators didn’t hesitate to rail against “idiotic” and “stupid” listeners. Welles and his crew, Dorothy Thompson declared, “have shown up the incredible stupidity, lack of nerve, and ignorance of thousands.”

Today, when we speak about people’s relationship to the internet, we tend to adopt the nonjudgmental language of computer science. Fake news was described as a “virus” spreading among users who have been “exposed” to online misinformation. The proposed solutions to the fake-news problem typically resemble antivirus programs: their aim is to identify and quarantine all the dangerous nonfacts throughout the web before they can infect their prospective hosts. One venture capitalist, writing on the tech blog Venture Beat, imagined deploying artificial intelligence as a “media cop,” protecting users from malicious content. “Imagine a world where every article could be assessed based on its level of sound discourse,” he wrote. The vision here was of the news consumers of the future turning the discourse setting on their browser up to eleven and soaking in pure fact. It’s possible, though, that this approach comes with its own form of myopia. Neil Postman, writing a couple of decades ago, warned of a growing tendency to view people as computers, and a corresponding devaluation of the “singular human capacity to see things whole in all their psychic, emotional, and moral dimensions.” A person does not process information the way a computer does, flipping a switch of “true” or “false.” One rarely cited Pew statistic shows that only four percent of American internet users trust social media “a lot,” which suggests a greater resilience against online misinformation than overheated editorials might lead us to expect. Most people seem to understand that their social-media streams represent a heady mixture of gossip, political activism, news, and entertainment. You might see this as a problem, but turning to Big Data—driven algorithms to fix it will only further entrench our reliance on code to tell us what is important about the world—which is what led to the problem in the first place. Plus, it doesn’t sound very fun.

The various efforts to fact-check and label and blacklist and sort all the world’s information bring to mind a quote, which appears in David Goodman’s book, from John Grierson, a documentary filmmaker: “Men don’t live by bread alone, nor by fact alone.” In the nineteen-forties, Grierson was on an F.C.C. panel that had been convened to determine how best to encourage a democratic radio, and he was frustrated by a draft report that reflected his fellow-panelists’ obsession with filling the airwaves with rationality and fact. Grierson said, “Much of this entertainment is the folk stuff . . . of our technological time; the patterns of observation, of humor, of fancy, which make a technological society a human society.”

In recent times, Donald Trump supporters are the ones who have most effectively applied Grierson’s insight to the digital age. Young Trump enthusiasts turned internet trolling into a potent political tool, deploying the “folk stuff” of the web—memes, slang, the nihilistic humor of a certain subculture of web-native gamer—to give a subversive, cyberpunk sheen to a movement that might otherwise look like a stale reactionary blend of white nationalism and anti-feminism. As crusaders against fake news push technology companies to “defend the truth,” they face a backlash from a conservative movement, retooled for the digital age, which sees claims for objectivity as a smoke screen for bias.

One sign of this development came last summer, in the scandal over Facebook’s “Trending” sidebar, in which curators chose stories to feature on the user’s home page. When the tech website Gizmodo reported the claim of an anonymous employee that the curators were systematically suppressing conservative news stories, the right-wing blogosphere exploded. Breitbart, the far-right torchbearer, uncovered the social-media accounts of some of the employees—liberal recent college graduates—that seemed to confirm the suspicion of pervasive anti-right bias. Eventually, Facebook fired the team and retooled the feature, calling in high-profile conservatives for a meeting with Mark Zuckerberg. Although Facebook denied that there was any systematic suppression of conservative views, the outcry was enough to reverse a tiny first step it had taken toward introducing human judgment into the algorithmic machine.

For conservatives, the rise of online gatekeepers may be a blessing in disguise. Throwing the charge of “liberal media bias” against powerful institutions has always provided an energizing force for the conservative movement, as the historian Nicole Hemmer shows in her new book, Messengers of the Right. Instead of focussing on ideas, Hemmer focusses on the galvanizing struggle over the means of distributing those ideas. The first modern conservatives were members of the America First movement, who found their isolationist views marginalized in the lead-up to the Second World War and vowed to fight back by forming the first conservative media outlets. A “vague claim of exclusion” sharpened into a “powerful and effective ideological arrow in the conservative quiver,” Hemmer argues, through battles that conservative radio broadcasters had with the F.C.C. in the nineteen-fifties and sixties. Their main obstacle was the F.C.C.’s Fairness Doctrine, which sought to protect public discourse by requiring controversial opinions to be balanced by opposing viewpoints. Since attacks on the mid-century liberal consensus were inherently controversial, conservatives found themselves constantly in regulators’ sights. In 1961, a watershed moment occurred with the leak of a memo from labor leaders to the Kennedy Administration which suggested using the Fairness Doctrine to suppress right-wing viewpoints. To many conservatives, the memo proved the existence of the vast conspiracy they had long suspected. A fund-raising letter for a prominent conservative radio show railed against the doctrine, calling it “the most dastardly collateral attack on freedom of speech in the history of the country.” Thus was born the character of the persecuted truthteller standing up to a tyrannical government—a trope on which a billion-dollar conservative-media juggernaut has been built.