Practical argument: A text and anthology - Laurie G. Kirszner, Stephen R. Mandell 2019

Ethical arguments

Strategies for argument

AT ISSUE

How Far Should Schools Go to Keep Students Safe?

Unfortunately, it is no longer unusual to read reports of shootings, robberies, muggings, and even murders in schools—both urban and rural. According to the Gun Violence Archive, from 2012 to 2018, there have been 239 school shootings nationwide, leaving 438 people wounded and 38 killed. But is this situation as bad as it seems? The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) points out that, the vast majority of school-age children will never experience lethal violence at school. In addition, a number of studies suggest that college campuses experience less crime than society in general. Even so, the 2007 Virginia Tech massacre and the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary have caused many people to worry that schools are no longer the safe environments they once were.

In response to pressure from parents, educators, students, and politicians, many public schools now require students to pass through metal detectors and teachers to lock classroom doors during school hours. Colleges have installed blue-light phones, card-access systems in dorms and labs, and surveillance cameras in parking garages and public areas. In addition, many colleges use text messages, automated phone calls, and emails to alert students and faculty to emergency situations.

Not everyone is happy about this emphasis on security, however. Some educators observe that public school buildings now look more like fortresses than places of learning. In addition, faculty members point out that colleges are supposed to promote free thought and that increased security undercuts this freedom by limiting access to campus and sanitizing the college experience. College students balk at having to wait in long lines to get into campus buildings as security guards examine and scan IDs.

Later in this chapter, you will be asked to think more about this issue. You will be given several research sources to consider and asked to write an ethical argument discussing how far schools should go to keep students safe.

What Is an Ethical Argument?

Ethics is the field of philosophy that studies the standards by which actions can be judged as right or wrong or good or bad. To make such judgments, we either measure actions against some standard (such as a moral rule like “Thou shall not kill”) or consider them in terms of their consequences. Usually, making ethical judgments means examining abstract concepts such as good, right, duty, obligation, virtue, honor, and choice. Applied ethics is the field of philosophy that applies ethics to real-life issues, such as abortion, the death penalty, animal rights, and doctor-assisted suicide.

An ethical argument focuses on whether something should be done because it is good or right (or not done because it is bad or wrong). For example, consider the following questions:

§ Does the United States have an obligation to help other countries?

§ Is physician-assisted suicide ever justified?

§ Is it wrong for Twitter to suspend people for posting inappropriate content?

§ Is it right for the government to collect Americans’ personal data?

§ Is the death penalty ever justified?

§ Do animals have rights?

Ethical arguments that try to answer questions like these usually begin with a clear statement that something is right or wrong and then go on to show how a religious, philosophical, or ethical principle supports this position. Consider how the last three questions on the list above can be examined in ethical arguments:

§ Is it right for the government to collect Americans’ personal data? You could begin your ethical argument by making the point that the government has a moral duty to protect its citizens. You could then go on to demonstrate that collecting personal data enables the United States government to accomplish this goal by addressing the threat of terrorism. You could end by saying that for this reason, the collection of personal data by the government is both moral and justified.

§ Is the death penalty ever justified? You could begin your ethical argument by pointing out that because killing in any form is immoral, the death penalty is morally wrong. You could go on to demonstrate that despite its usefulness—it rids society of dangerous criminals—the death penalty hurts all of us. You could conclude by saying that because the death penalty is so immoral, it has no place in a civilized society.

§ Do animals have rights? You could begin your ethical argument by pointing out that like all thinking beings, animals have certain basic rights. You could go on to discuss the basic rights that all thinking beings have—for example, the right to respect, a safe environment, and a dignified death. You could conclude by saying that the inhumane treatment of animals should not be tolerated, whether those animals are pets, live in the wild, or are raised for food.

Stating an Ethical Principle

The most important part of an ethical argument is the ethical principle—a general statement about what is good or bad, right or wrong. It is the set of values that guides you to an ethically correct conclusion.

§ You can show that something is good or right by establishing that it conforms to a particular moral law or will result in something good for society. For example, you could argue in favor of a policy restricting access to campus by saying that such a policy will reduce crime on campus or will result in a better educational experience for students.

§ You can show that something is bad or wrong by demonstrating that it violates a moral law or will result in something bad for society. For example, you could argue against the use of physician-assisted suicide by saying that respect for individual rights is one of the basic principles of American society and that by ignoring this principle we undermine our Constitution and our way of life.

Whenever possible, you should base your ethical argument on an ethical principle that is self-evident—one that needs no proof or explanation. (By doing so, you avoid having to establish the principle that is the basis for your essay.) Thomas Jefferson uses this strategy in the Declaration of Independence. When he says, “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” he is saying that the ethical principle that supports the rest of his argument is so basic (and so widely accepted) that it requires no proof—in other words, that it is self-evident. If readers accept Jefferson’s assertion, then the rest of his argument—that the thirteen original colonies owe no allegiance to England—will be much more convincing. (Remember, however, that the king of England, George III, would not have accepted Jefferson’s assertion. For him, the ethical principle that is the foundation of the Declaration of Independence was not at all self-evident.)

Keep in mind that an ethical principle has to be self-evident to most of your readers—not just to those who agree with you or hold a particular set of religious or cultural beliefs. Using a religious doctrine as an ethical principle has its limitations, so doctrines that cut across religions and cultures are more suitable than those that do not. For example, every culture prohibits murder and theft. But some other doctrines—such as the Jehovah’s Witness prohibition against blood transfusion or the Muslim dietary restrictions—are not universally accepted. In addition, an ethical principle must be stated so that it applies universally. For example, not all readers will find the statement, “As a Christian, I am against killing and therefore against the death penalty” convincing. A more effective statement would be, “Because it is morally wrong, the death penalty should be abolished” or “With few exceptions, taking the life of another person is never justified, and there should be no exception for the government.”

Ethics versus Law

Generally speaking, an ethical argument deals with what is right and wrong, not necessarily with what is legal or illegal. In fact, there is a big difference between law and ethics. Laws are rules that govern a society and are enforced by its political and legal systems. Ethics are standards that determine how human conduct is judged.

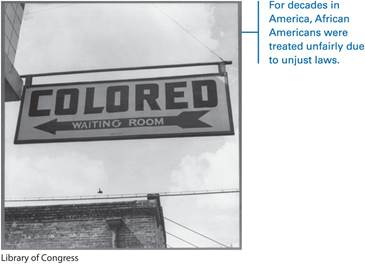

Keep in mind that something that is legal is not necessarily ethical. As Socrates, St. Augustine, Henry David Thoreau, and Martin Luther King Jr. have all pointed out, there are just laws, and there are unjust laws. For example, when King wrote his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” segregation was legal in many Southern states. According to King, unjust laws—such as those that institutionalized segregation—are out of harmony with both moral law and natural law. As King wrote, “We should never forget that everything Adolf Hitler did in Germany was ’legal.’ ” For King, the ultimate standard for deciding what is just or unjust is morality, not legality.

There are many historical examples of laws that most people would now consider unjust:

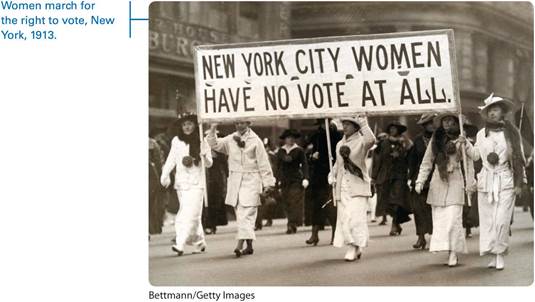

§ Laws against woman suffrage: In the late eighteenth century, various states passed laws prohibiting women from voting.

§ Jim Crow laws: In the mid-nineteenth century, laws were passed in the American South that restricted the rights of African Americans.

§ Nuremberg laws: In 1935, Nazi Germany passed a series of laws that deprived Jews of German citizenship. As a result, Jews could no longer vote, hold public office, or marry a German national.

§ Apartheid laws: Beginning in 1948, South Africa enacted laws that defined and enforced racial segregation. These laws stayed in effect until 1994, when Nelson Mandela was elected South Africa’s first black president.

Today, virtually everyone would agree that these laws were wrong and should never have been enacted. Still, many people obeyed these laws, with disastrous consequences. These consequences illustrate the importance of doing what is ethically right, not just what is legally right.

The difference between ethics and law can be seen in many everyday situations. Although we have no legal obligation to stop a drunk friend from driving, most people would agree that we should. In addition, although motorists (or even doctors) have no legal obligation to help at the scene of an accident, many people would say that it is the right thing to do.

An example of a person going beyond what is legally required occurred in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1995, when fire destroyed Malden Mills, the largest employer in town. Citing his religious principles, Aaron Feuerstein, the owner of the mill and inventor of Polartec fleece, decided to rebuild in Lawrence rather than move his business overseas as many of his competitors had done. In addition, he decided that for sixty days, all employees would receive their full salaries—even though the mill was closed. Feuerstein was not required by law to do what he did, but he decided to do what he believed was both ethical and responsible.

Understanding Ethical Dilemmas

Life decisions tend to be somewhat messy, and it is often not easy to decide what is right or wrong or what is good or bad. In many real-life situations, people are faced with dilemmas—choices between alternatives that seem equally unfavorable. An ethical dilemma occurs when there is a conflict between two or more possible actions—each of which will have a similar consequence or outcome.

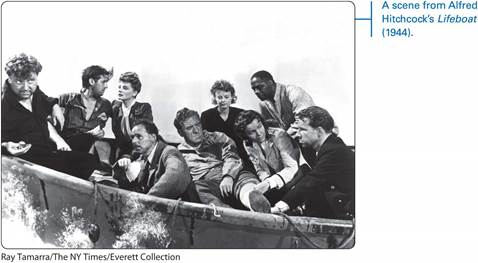

The classic ethical dilemma is the so-called lifeboat dilemma. In this hypothetical situation, a ship hits an iceberg, and survivors are crowded into a lifeboat. As a storm approaches, the captain realizes that he is faced with an ethical dilemma. If he does nothing, the overloaded boat will capsize, and all the people will drown. If he throws some of the passengers overboard, he will save those in the boat, but those he throws overboard will drown.

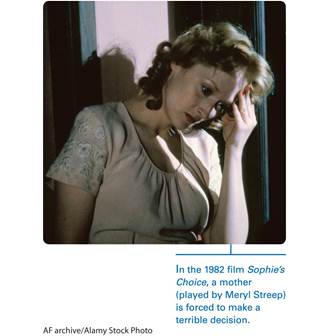

Another ethical dilemma occurs in William Styron’s 1979 novel Sophie’s Choice. The novel’s narrator is fascinated by the story of Sophie, a woman who was arrested by the Nazis and sent along with her two children to the Auschwitz concentration camp. When she arrived, she was given a choice by a sadistic guard: one of her children would go to the gas chamber and one would be spared, but she had to choose which one. If she did not choose, both children would be murdered.

Ethical dilemmas are not just the stuff of fiction; people confront them every day. For example, an owner of a business who realizes that costs must be cut faces an ethical dilemma. If the owner takes no action, the business will fail, and all the employees will lose their jobs. If the owner lays off some employees, they will be hurt, but the business might be saved and so might the jobs of the remaining workers. A surgeon who has to separate conjoined twins who share a heart also faces an ethical dilemma. If the surgeon does nothing, both twins will die, but if the surgeon operates, one of the twins might live although the other will be sacrificed.

Often, the only way to resolve an ethical dilemma is to choose the lesser of two evils. Simple “right or wrong” or “good versus bad” prescriptions will not work in such cases. For example, killing may be morally, legally, and ethically wrong, but what if it is done in self-defense? Stealing is also wrong, but what if a person steals food to feed a hungry child? Although it may be tempting to apply clear ethical principles, you should be careful not to oversimplify the situations you are writing about.

![]() EXERCISE 15.1 CHOOSING AN ETHICAL PRINCIPLE

EXERCISE 15.1 CHOOSING AN ETHICAL PRINCIPLE

Consider the following topics for ethical arguments. Then, decide what ethical principle you could use for each argument. For example, if you were to argue against the legalization of marijuana, you could use the principle that getting high prevents people from making wise decisions as the basis for your argument. You could then demonstrate that society is harmed when large numbers of people smoke marijuana.

§ The federal government should (or should not) legalize marijuana.

§ A student’s race should (or should not) be a consideration in college admissions.

§ Homeless people should (or should not) be forcibly removed from city streets.

§ Everyone should (or should not) be required to sign an organ-donor card.

§ A witness to academic cheating should (or should not) report the cheater.

![]() EXERCISE 15.2 IDENTIFYING UNJUST LAWS

EXERCISE 15.2 IDENTIFYING UNJUST LAWS

Make a list of some rules or laws that you think are unjust. Then, next to each item on your list, write down the ethical principle on which you based your conclusion.

![]() EXERCISE 15.3 ANALYZING VISUAL ARGUMENTS

EXERCISE 15.3 ANALYZING VISUAL ARGUMENTS

Look at the following two images. In what sense do they make ethical arguments? What ethical principle underlies each image?

The text above the photo reads, Ride Hard, and the text below the photo reads, Tread Lightly. The text at the bottom portion of the poster reads, (bold) Stay on designated trails. (end bold) Being responsible doesn’t mean being boring. Have a blast out there. Just use common sense and simple outdoor ethics to keep your riding areas beautiful, healthy, and open. The phone number at the bottom left portion reads, 1.800.966.9900. The text tread lightly on Land and water is next to an illustration of a finger print on the bottom center portion of the poster. On the bottom right portion of the poster is the text, www.treadlightly.org.

The text beside the photo reads, (bold) (uppercase) Buying animals is killing animals. (end bold) (end uppercase). Save a homeless dog or cat (m dash) always adopt and never buy. The peta logo is at the bottom right corner of the poster with the text above it reading, (bold) Kellan Lutz (end bold) and (bold) Kola (end bold) for Peta.

Structuring an Ethical Argument

In general, an ethical argument can be structured in the following way.

§ Introduction: Establishes the ethical principle and states the essay’s thesis

§ Background: Gives an overview of the situation

§ Ethical analysis: Explains the ethical principle and analyzes the particular situation on the basis of this principle

§ Evidence: Presents points that support the thesis

§ Refutation of opposing arguments: Addresses arguments against the thesis

§ Conclusion: Restates the ethical principle as well as the thesis; includes a strong concluding statement

ARE COLLEGES DOING ENOUGH FOR NONTRADITIONAL STUDENTS?

CHRIS MUÑOZ

![]() The following student essay contains all the elements of an ethical argument. The student takes the position that colleges should do more to help nontraditional students succeed.

The following student essay contains all the elements of an ethical argument. The student takes the position that colleges should do more to help nontraditional students succeed.

ñ

First paragraph: Colleges and universities are experiencing an increase in the number of nontraditional students, and this number is projected to rise. Although these students enrich campus communities and provide new opportunities for learning, they also present challenges. Generally, nontraditional students are older, attend school part-time, and are self-supporting. With their years of life experience, they tend to have different educational goals from other students (a corresponding margin note reads, Ethical principle established). Although many schools recognize that nontraditional students have unique needs, most schools ignore these needs and unfairly continue to focus on the “typical” student. As a result, nontraditional students frequently do not have the same access to educational opportunities as their younger counterparts (a corresponding margin note reads, Thesis statement). To solve this problem, universities need to do more to ensure equitable treatment of nontraditional students.

Second paragraph: Most people’s assumptions about who is enrolled in college are out of date. According to the educational policy scholar Frederick Hess, only 15 percent of all undergraduates attend a four-year college and live on campus. In other words, so-called typical college students are in the minority. In fact, 38 percent of today’s undergraduates are over age twenty-five, 37 percent attend part-time, 32 percent work full-time, and many are responsible for dependents. In addition, real-world responsibilities cause many nontraditional students to delay starting school, to take a break in the middle, or to drop out entirely. According to Kris MacDonald, nearly 70 percent of all nontraditional students drop out of college. Although some argue that schools already provide extra help, such as advising and tutoring, others point out that asking nontraditional students to adapt to an educational model that focuses on the traditional student is a form of discrimination against them. (A corresponding margin note read, Background: Gives an overview of the situation.)

Second paragraph continues as follows:

These people recommend that schools institute policies that reflect the growing number of nontraditional students on campus and address the challenges that these students face every day.

Third paragraph reads as follows:

Most people would agree that diversity is highly valued on college campuses. In fact, most universities go to great lengths to admit a diverse group of students—including nontraditional students. However, as Jacqueline Muhammad points out, universities do not serve these students well after they are enrolled. By asking nontraditional students to assimilate into the traditional university environment, colleges marginalize them, and this is not ethical. Evidence of this marginalization is not difficult to find. As one college student acknowledges, “These students have a lot to offer, but often they don’t feel included” (qtd. In Muhammad). This lack of inclusion is seen in many areas of campus life, including access to classes and services, availability of relevant programs and courses, and use of fair and appropriate classroom practices. To be fair, a university should ensure that all of its students have equal to a meaningful and fulfilling education. By maintaining policies and approaches that are not inclusive, colleges marginalize nontraditional students. (A margin note corresponding to the paragraph reads, Ethical analysis: Presents the ethical principle and analyzes the situation on the basis of this principle.)

Fourth paragraph: To ensure the fair treatment of nontraditional students, colleges need to remove the barriers those students face (a corresponding margin note reads, Evidence: First point in support of the thesis). One of the first barriers that nontraditional students face is difficulty gaining access to classes and student services. Academic schedules, including the academic calendar and class times, frequently exclude working adults and parents. As Frederick Hess explains, “A semester system . . . works well for 19-year-olds used to the rhythms of high school, but that’s hugely frustrating for workers.” In addition, unless classes and services are available in the evening, on weekends, or online, they are inaccessible to many students. As one professional advocate for nontraditional students explains, “Most nontraditional students have obligations during the day that make it difficult to access on-campus resources that are only open during business hours” (qtd. in Muhammad). This situation makes it difficult (and sometimes impossible) for nontraditional students to schedule required courses or to get extra help, such as tutoring. As long as these barriers to equal access exist, nontraditional students will always be “second-class citizens” in the university.

Text continues as follows:

Fifth paragraph: Schools also need to stop devaluing the kinds of programs in which nontraditional students tend to enroll. Research shows that the reasons older students want to continue their educations “indicate high motivation and commitment, but require accommodations to instruction” (Newman, Deyoe, and Seelow 107). Many are taking courses in order to return to work, change careers, or improve their chances for a promotion. According to Hess, although the greatest demand is for associate’s degrees, over 50 percent of nontraditional students are seeking “subbaccalaureate” certification credentials. As Hess demonstrates, certification programs are considered to be marginal, even in community colleges. One reason for this situation is that most schools still judge their own worth by factors—such as academic ranking or grant money—that have little to do with teaching career skills. By devaluing practical training that certification programs offer, schools are undermining the educational experience that many nontraditional students want. (A margin note corresponding to the paragraph reads, Evidence: Second point in support of the thesis.)

Sixth paragraph: Finally, universities need to do more to encourage inclusive teaching approaches. According to Joshua L. Carreiro and Brian P. Kapitulik, most educators assume their students are “traditional”—that they are recent high school graduates from middle-class backgrounds with little work experience (232). As a result, nontraditional students “are frequently mis-served by direct instruction due to financial, family, career, or learning style preferences” (Newman, Deyoe, and Seelow 107). Carreiro and Kapitulik conclude that these assumptions result in “an exclusive classroom environment” that excludes and marginalizes nontraditional students (246). One way of addressing this problem is for universities to expand online education offerings. Online courses enable nontraditional students to gradually assimilate into the college environment and to work at their own pace without fear of ridicule. Universities can also encourage instructors to develop new teaching approaches. If instructors want to be more inclusive, they can acknowledge diversity by engaging students in diverse ways of thinking and learning (Hermida). For example, they can ask students to relate course material to their own experiences, and they can bring in guest speakers from a variety of backgrounds. By acknowledging the needs of nontraditional students, instructors can provide a better education for all students. (A margin note corresponding to the paragraph reads, Evidence: Third point in 6 support of thesis)

Text continues as follows:

Seventh paragraph: Not everyone believes that colleges and universities need to change their basic assumptions about education (a corresponding margin note reads, Refutation of opposing arguments). They concede that nontraditional students might need extra support, but they say that these students are adults and should be able to fend for themselves. Students’ commitments outside of school—for instance, children or a full-time job—should not be a concern for colleges and universities. If these students need help, they can get support from one another, or they can turn to student-led organizations. Even those educators who are sympathetic to nontraditional students suggest that extra mentoring or advising is all that is necessary. However, the problems faced by these students need to be addressed, and according to Hermida, by ignoring institutional barriers and biases, colleges and universities are essentially burying their heads in the sand (22). To be more welcoming to nontraditional students, universities must fundamentally change some of the structures and practices that have traditionally defined them. Ultimately, everyone—the schools, the communities, and the students—will benefit from these adjustments. According to Hermida, many of today’s students are nontraditional (20). Most of the current research suggests that inclusion is their most pressing concern. As this population continues to grow, say Newman, Deyoe, and Seelow, educators should focus on offering “clear objectives, direct ties to life experience, and multiple opportunities” for nontraditional students to engage in the college community (122). Giving preferential treatment to some students while ignoring the needs of others is ethically wrong, so schools need to work harder to end discrimination against this increasingly large group of learners (a corresponding margin note reads, Concluding statement).

Works Cited

Carreiro, Joshua L., and Brian P. Kapitulik. “Budgets, Board Games, and Make Believe: The Challenge of Teaching Social Class Inequality with Nontraditional Students.” American Sociologist, vol. 41, no. 3, Oct. 2010, pp. 232—48. Academic Search Complete, www.ebscohost.com/academic.

Hermida, Julian. “Inclusive Teaching: An Approach for Encouraging Nontraditional Student Success.” International Journal of Research and Review, vol. 5, no. 1, Oct. 2010, pp. 19—30. Academic Search Complete, www.ebscohost.com/academic.

Hess, Frederick. “Old School: College’s Most Important Trend Is the Rise of the Adult Student.” The Atlantic, 28 Sept. 2011, www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2011/09/old-school-colleges-most-important-trend-is-the-rise-of-the-adult-student/245823/.

MacDonald, Kris. “A Review of the Literature: The Needs of Non-Traditional Students in Postsecondary Education.” Strategic

Management Quarterly, 3 Jan. 2018, www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/sem3.20115.

Muhammad, Jacqueline. “New Coordinator to Address Nontraditional Student Needs.” Daily Egyptian, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, 8 Dec. 2011, archives.dailyegyptian.com/siu-2011/2011/12/8/new-coordinator-to-address-non-traditional-student-needs.html.

Newman, Dianna L., Meghan Morris Deyoe, and David Seelow. “Serving Nontraditional Students: Meeting Needs through an Online Writing Program.” Models for Improving and Optimizing Online and Blended Learning in Higher Education, edited by Jared Keengwe and Joachim Jack Agamba, IGI Global, 2015, pp. 106—28.

GRAMMAR IN CONTEXT

Subordination and Coordination

When you write an argumentative essay, you need to show readers the logical and sequential connections between your ideas. You do this by using coordinating conjunctions and subordinating conjunctions—words that join words, phrases, clauses, or entire sentences. Be sure to choose conjunctions that accurately express the relationship between the ideas they join.

Coordinating conjunctions—and, but, for, nor, or, so, and yet—join ideas of equal importance. In compound sentences, they describe the relationship between the ideas in the two independent clauses and show how these ideas are related.

§ “Colleges and universities are experiencing an increase in the number of nontraditional students, and this number is projected to rise.” (And indicates addition.) (para. 1)

§ “These students have a lot to offer, but often they don’t feel included.” (But indicates contrast or contradiction.) (3)

Subordinating conjunctions—after, although, because, if, so that, where, and so on—join ideas of unequal importance. In complex sentences, they describe the relationship between the ideas in the dependent clause and the independent clause and show how these ideas are related.

§ “Although these students enrich campus communities and provide new opportunities for learning, they also present challenges.” (Although indicates a contrast.) (1)

§ “Although many schools recognize that nontraditional students have unique needs, most schools ignore these needs and unfairly continue to focus on the ’typical’ student.” (Although indicates a contrast.) (1)

§ “As long as these barriers to equal access exist, nontraditional students will always be ’second-class citizens’ in the university.” (As long as indicates a causal relationship.) (4)

§ “If instructors want to be more inclusive, they can acknowledge diversity by engaging students in diverse ways of thinking and learning.” (If indicates condition.) (6)

![]() EXERCISE 15.4 IDENTIFYING ELEMENTS OF AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

EXERCISE 15.4 IDENTIFYING ELEMENTS OF AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

The following essay includes the basic elements of an ethical argument. Read the essay, and then answer the questions that follow it, consulting the outline on page 523 if necessary.

THE ETHICAL CASE FOR EATING ANIMALS

SHUBHANKAR CHHOKRA

This essay was published in the Harvard Crimson student newspaper on March 6, 2015.

We were transplanting a row of eggplant as quickly as we could, trying to finish before it got too hot. With one hand, Jake was placing seedlings a foot away from each other with uncanny precision and with the other he was stopping Maggie the dog from prancing all over them. I was right behind them covering the roots with soil, crawling on my stomach along the furrow like a soldier through a trench.

Jake usually got philosophical when we transplanted—it probably had something to do with the wealth of intrigue offered by the task of putting plants into dirt. So I saw it coming when he asked me about halfway down the furrow about my thoughts on vegetarianism. Without looking up, I recited the religious and cultural implications of eating meat for certain people, talked about the potential health benefits, and said something about as vague and unsubstantiated as, “It’s the ethical thing to do.” He didn’t say anything for a while. But Jake was a high school teacher first and a farmer second, and his instincts as the former must have kicked in.

“Ever hear of the Siberian fox experiment?” he asked.

“Jake was a high school teacher first and a farmer second, and his instincts as the former must have kicked in.”

He told me, once he saw my blank face, about research that sounded like it came out of a science fiction novel. Against the backdrop of Soviet totalitarianism, scientist Dmitriy Belyaev attempted to recreate the evolution of wolves into dogs in a secret laboratory in some unexplored recess of Siberia. He and his team bred silver foxes, a cousin to the dog that had never been domesticated before, over multiple generations, selecting for traits like approachability and friendliness around humans.

After mere decades, Belyaev did what was previously thought took millennia. Fourth generation foxes started showing the behavioral traits of tameness like wagging their tails and jumping into the laps of researchers. They also had what researchers call the “domestication phenotype”—physiological characteristics like floppier ears, curlier tails, and spottier coats. More strikingly, foxes born to aggressive mothers, but nurtured by tame ones, were nonetheless aggressive. Fifty years later, scientists continue his work, providing even more compelling evidence of the previously unthinkable—certain animals may be genetically predisposed to human contact, to domesticity.

Domesticity is a concept that’s difficult to precisely define, but at its core, it is the modification of animals over multiple generations for human benefit. The most prevalent use of domesticated animals is to produce meat, an exercise that many proponents of ethical vegetarianism take issue with on the grounds that since animals are sentient beings of similar moral value to humans, rearing and killing them cannot be justified. The doctrine of animal liberationism, defined by people like Peter Singer and organizations like PETA, distinguishes humans from the rest of the Animal Kingdom only in one regard: moral agency, which compels us to right our wrongs and to stop exploiting the farm animal.

But what Belyaev’s research demonstrates—an idea that took a lot of time for me to accept after Jake introduced it to me—is that historically, there have been more factors than just human intention in the process that has given us the beef steer and the broiler chicken. The ancestor of many of the animals we consider food species like pigs, cattle, and sheep derived much of their evolutionary competitiveness from mutations that caused them to be less afraid of humans, presenting an opportunity for humans to engage in symbiotic husbandry. Natural selection preceded artificial selection. At the risk of sounding reductive, farm animals were made to be farmed.

Animal liberationists conflate sentience with moral value, oversimplifying the similarity between meat animals and humans and mischaracterizing human moral agency. Animals and humans are fundamentally and genetically different, and the moral responsibility of the human to animals exists only insofar as the need to care for them well. This human prerogative however cannot be overstated. Environmentalist Wendell Berry sets a good standard in his essay “The Pleasures of Eating” for responsible eating practices: “If I am going to eat meat,” he wrote, “I want it to be from an animal that has lived a pleasant, uncrowded life outdoors, on bountiful pasture, with good water nearby and trees for shade.”

Industrial or otherwise intensive farms, however, produce most of the meat Americans eat by cruelly confining animals to inhabitable enclosures and slaughtering them in ways that yield inconceivable pain. Cows spend most of their lives walking knee-deep in their own waste. Chicken are fed and drugged until their breasts are so large that they spend the latter part of their lives keeled over. To that end, ethical vegetarians are only guilty of erring on the side of caution, refusing to be implicated in a process that is morally unacceptable regardless of the genetic origins of domesticity.

Man’s control of the land is his crowning achievement. He revolutionized the human diet by domesticating the plant and to the extent he was involved in domesticating the animal, he did so justifiably. Jake didn’t change my eating practices in just one day. No, that would be a pedagogical nightmare. But he did accomplish what I think he wanted to. He challenged me to substantiate and eventually redefine my claims on ethical prudence. And more importantly, he made me thankful for gifts of nature and conversations like these.

Identifying the Elements of an Ethical Argument

1. What is the Siberian fox experiment? Why does Chhokra discuss it in his essay?

2. Look up the definition of domesticity? What does Chhokra mean when he says, “Domesticity is a concept that’s difficult to precisely define” (para. 6)?

3. What ethical principle does Chhokra apply in his essay? At what point does he state this principle? Why do you think he states it where he does?

4. What does Chhokra mean when he says, “Animal liberationists conflate sentience with moral value, oversimplifying the similarity between meat animals and humans and mischaracterizing moral agency” (8)?

5. What is the problem with the way industrial farms raise animals? According to Chhokra, why is this method of producing meat “morally unacceptable” (9)?

6. In his essay, Chhokra uses all three appeals—logos, pathos, and ethos. Locate examples of each. How effective is each appeal? Explain.

7. What strategy does Chhokra use to conclude his essay? Do you think that his conclusion is effective? Explain.

![]() READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

How Far Should Schools Go to Keep Students Safe?

Go back and reread the At Issue box at the beginning of the chapter, which gives background on how far schools should go to keep their students safe. Then, read the sources on the pages that follow.

As you read this source material, you will be asked to answer some questions and to complete some simple activities. This work will help you understand both the content and the structure of the selections. When you are finished, you will be ready to write an ethical argument that takes a position on the topic, “How Far Should Schools Go to Keep Students Safe?”

SOURCES

Evie Blad, “Do Schools’ ’Active-Shooter’ Drills Prepare or Frighten?,” page 533 |

Timothy Wheeler, “There’s a Reason They Choose Schools,” page 538 |

Sasha Abramsky, “The Fear Industry Goes Back to School,” page 541 |

Michael W. Goldberg, “I’m a School Psychologist—And I Think Teachers Should Be Armed,” page 548 |

Vann R. Newkirk II, “Arming Educators Violates the Spirit of the Second Amendment,” page 551 |

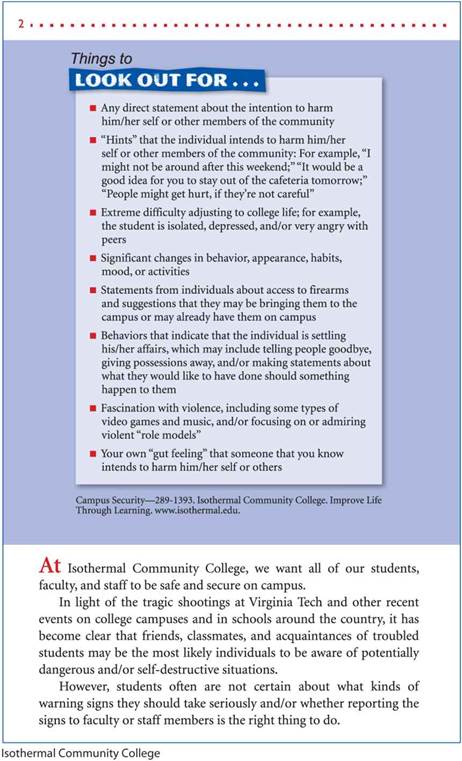

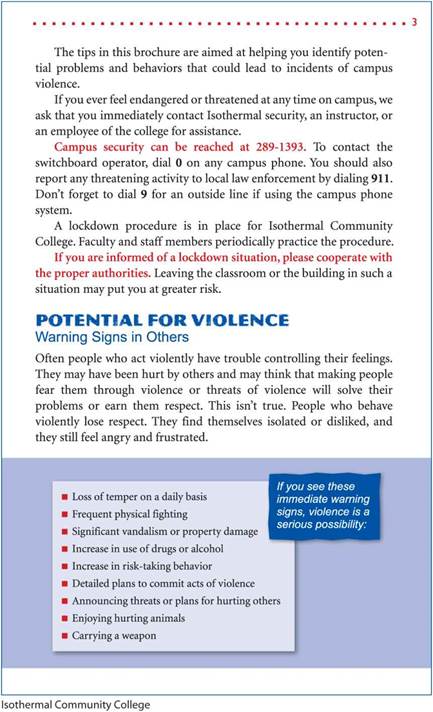

Isothermal Community College, “Warning Signs: How You Can Help Prevent Campus Violence” (brochure), page 554 |

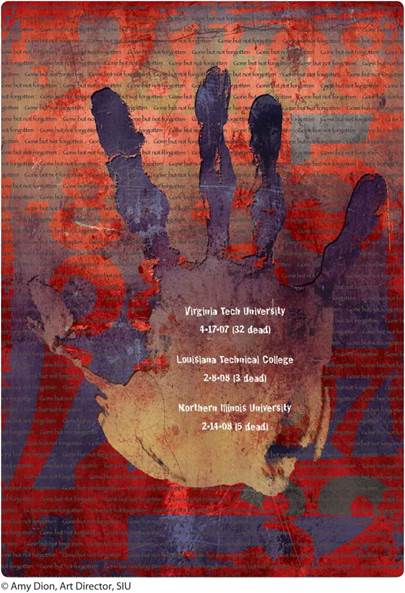

Visual Argument: Amy Dion, “Gone but Not Forgotten” (poster), page 558 |

DO SCHOOLS’ “ACTIVE-SHOOTER” DRILLS PREPARE OR FRIGHTEN?

EVIE BLAD

This essay is from the September 19, 2017, issue of Education Week.

On “safety days,” elementary students in Akron, OH, learn a new vocabulary word: barricade.

School-based police officers tell students as young as kindergartners how to stack chairs and desks against the classroom door to make it harder for “bad guys” to get in. “Make the classroom more like a fort,” an officer says in a video of the exercise.

If a teacher asks you to climb out a window, listen to them, the officers instruct. And, in the unlikely event a “bad guy” gets into the classroom, scream and run around to distract him, officers tell students.

For some parents, the idea of such instruction is chilling. Others, though, say it’s a sad, but necessary sign of the times.

Children around the country are increasingly receiving similar training as schools adopt more elaborate safety drills in response to concerns about school shootings. That leaves schools with a profound challenge: how to prepare young students for the worst, without provoking anxiety or fear.

“That’s the fine balance,” said Dan Rambler, the Akron school district’s director of student services and safety. “We’re not trying to panic people.” A growing number of districts around the country have replaced or supplemented traditional lockdown drills—which teach students to quietly hide in their classrooms in the event of a school shooting—with multi-option response drills, which teach them a variety of ways to respond and escape.

Most controversially, the drills teach young students how to “counter” a shooter by running in zig-zag patterns, throwing objects, and screaming to make it difficult for a gunman to focus and aim.

Akron uses a protocol called ALICE (Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter, Evacuate). It was developed by former police officer Greg Crane and his wife, Lisa Crane, a former school principal, after the 1999 shootings at Colorado’s Columbine High School.

It’s grown more popular following the 2012 shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, CT. About 4,000 school districts and 3,500 police departments have ALICE-trained personnel.

School safety consultant Kenneth Trump, who regularly writes about ALICE training, says it’s not supported by evidence and “preys on the emotions of today’s active shooter frenzy that is spreading across the nation.” Trump and other critics say schools shouldn’t train young children in the ALICE response when school shootings, typically the focus of such drills, are statistically rare.

But fires are also rare, Rambler said, and that doesn’t stop schools from conducting regular fire drills.

Greg Crane, ALICE’s creator, says schools put children in danger if they teach them to be “static targets.”

Parents “don’t have any problem discussing an abduction and giving children quite aggressive tactics in response,” Crane said. “What do we tell kids in stranger danger? Anything but go with the guy. Bite, kick, yell. Anything but go sit in the corner and be quiet.”

Growing Use of Drills

Discussions over security are often sparked by media coverage of shootings. Recently, a student at a Washington state high school shot and killed a classmate and injured three others before he was subdued by a janitor.

“70 percent of public schools drilled students on how to respond to a school shooting.”

Federal data show a growing use of school-shooter drills, though it doesn’t distinguish between lockdown drills and responses like ALICE. In the 2013—14 school year, 70 percent of public schools drilled students on how to respond to a school shooting, including 71 percent of elementary schools, according to the most recent data available. In 2003—4, 47 percent of schools involved students in shooter drills.

A 2013 federal report, created in response to Sandy Hook, outlined a safety response that called on school staff to “consider trying to disrupt or incapacitate the shooter by using aggressive force and items in their environment, such as fire extinguishers, and chairs. It didn’t advocate involving students.

That report, released by the U.S. Department of Education on behalf of a group of federal agencies, drew concern from some school safety consultants who said such a “run, hide, fight” approach is unproven by research and may even be dangerous in the event of an actual shooting.

But it also inspired states and districts to update safety plans, leading many to adopt ALICE and similar training. A subsequent report by a task force convened by Ohio’s attorney general, for example, recommended that schools train students and staff that, if a shooter enters a classroom, they try to interfere with his shooting accuracy by throwing books, computers, and phones. They may also need to subdue the intruder, the report said.

In Akron, parents can opt their children out of the training, though few do. Elementary students are told briefly about countering techniques, but the focus of their discussions is on following teachers’ directions in unpredictable situations. In middle school, training is “a little more complete,” sometimes including foam props that students throw at school police officers as practice.

Countering an intruder “is literally the last resort,” Rambler said. “That is, ’Do whatever you have to to stay alive.’ It’s not, ’Go find the gunman and throw something at them.’ ”

Planning a Response

Greg Crane said schools decide how detailed they want to be in their hypothetical discussions of violence, but most involve students in some level of training.

The Cranes worked with a children’s author to publish a book called I’m Not Scared . . . I’m Prepared! that many schools use to train younger students. But some parents have been concerned about what some districts teach in ALICE drills, particularly when it comes to the counterstep.

In 2015, an Alabama middle school made headlines when its principal asked students to keep canned goods in their desks to hurl at attackers. At the time, ALICE co-founder Lisa Crane said the use of canned goods is not something ALICE trainers would advocate, but it’s also not something they would discourage.

In some districts, parents have started petitions or turned out to school board meetings in opposition to active-shooter drills, saying they don’t want to expose their young children to such discussions of violence.

“My daughter is 8 years old and she reads the newspaper and she gets nervous about stories about murders and other things happening in the neighborhood, so I’m very concerned about what impact it will have on her to be told that there’s a potential that someone might walk through the door and shoot her classroom,” a father said at a public meeting after the Anchorage district announced ALICE training plans last year.

At the National Association of School Resource Officers (NASRO) conference in Washington in July, Officer Ingrid Herriott told school-based police officers and safety directors how she customized ALICE training for elementary, middle, and high school students when she was a school resource officer at Southwest Allen County Schools in Fort Wayne, IN.

She showed a video she said schools could use to explain ALICE to elementary school children. In it, a school officer explains “stranger danger” to a plush dog named Safety Pup. Police officers are in uniforms, teachers have lanyards and name tags, and strangers are other adults students don’t recognize, the video says. The officer then explains ALICE, advising students to listen to their teacher for directions.

Middle school students quickly learn to barricade doors with desks, Herriott said. She walked middle school students through drills by showing videos produced by the district’s high school students using fake guns to act out school intruder scenarios. In one such video, a student in a library pretends to hit the gunman over the head with a chair.

At that age, the idea of a shooting “isn’t something that’s above and beyond what they are seeing in the media and the video games they are playing,” Herriot said. High school students were given internet surveys after training to learn about concerns, and had principals make follow-up videos to respond to those concerns.

NASRO worked with the National Association of School Psychologists to address concerns about the psychological effects of safety drills. Recommendations call for plans that are as sensitive to local and regional concerns, like wildfires and earthquakes, as they are to statistically less probable events, like shootings.

Steve Brock, a professor of school psychology at California State University, Sacramento, helped draft that guidance. He said there’s not enough research to support ALICE and similar training in schools.

Minimizing Student Anxiety

The most important thing a teacher can do in a shooting situation is lock the classroom door, Brock said, and it’s not necessary to “unnecessarily frighten” students by walking them through more elaborate hypothetical scenarios.

“When it comes to these kinds of activities, schools need to proceed cautiously,” he said.

Brock advocates for lockdown drills, which he calls “tried and true” for a variety of crises, ranging from intruders to an intoxicated parent. Such drills have been shown to lessen student anxiety. Brock recommends schools train young students to pretend there’s a strange dog in the hallway that they are trying to stay safe from, rather than talking about “bad guys” or shootings.

But some parents and teachers say responses like ALICE ease their fears that children would be “sitting ducks” in a shooting situation.

After Matt Holland, a third-grade teacher in Alexandria, VA, learned about ALICE in his own staff training this summer, he called his 7-year-old daughter’s school in a neighboring district to ask leaders to transition away from a lockdown approach.

“While, yes, statistically speaking, the chances [of a shooting] are very slim,” Holland said, “I don’t want, heaven forbid, something to happen to my students or my daughter and to say, ’There was a small chance it would happen, and it happened. And no one ever planned for it.’ ”

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

1. Blad begins her essay by describing an active-shooter instruction session. Is this an effective opening strategy? Why or why not? What other strategy should Blad have used?

2. In paragraph 10, Blad refers to Kenneth Trump, who says that ALICE training is not supported by any evidence that it works. In paragraph 17, a group of school-safety consultants say that ALICE training was “unproven by research and may even be dangerous in the event of an actual shooting.” Does Blad adequately address these criticisms? Explain.

3. What is the difference between a “lockdown drill” and ALICE training? Which do you think would be more effective when confronting an active shooter?

4. Why do some parents oppose active-shooter drills? Do you agree or disagree with them? In what sense do active shooter drills present these parents with an ethical dilemma?

5. In her conclusion, Blad quotes Matt Holland, a third-grade teacher, who acknowledges that “chances [of a shooting] are very slim” (para. 37). Does this weaken the argument in favor of active shooter drills? Explain.

6. Throughout her essay, Blad attempts to answer the question she asks in her title. Does she succeed? If not, why not?

THERE’S A REASON THEY CHOOSE SCHOOLS

TIMOTHY WHEELER

This article is from the October 11, 2007, issue of National Review.

Wednesday’s shooting at yet another school has a better outcome than most in recent memory. No one died at Cleveland’s Success Tech Academy except the perpetrator. The two students and two teachers he shot are in stable condition at Cleveland hospitals.

What is depressingly similar to the mass murders at Virginia Tech and Nickel Mines, Pennsylvania, and too many others was the killer’s choice of venue—that steadfastly gun-free zone, the school campus. Although murderer Seung-Hui Cho at Virginia Tech and Asa Coon, the Cleveland shooter, were both students reported to have school-related grudges, other school killers have proved to be simply taking advantage of the lack of effective security at schools. The Bailey, Colorado, multiple rapes and murder of September 2006, the Nickel Mines massacre of October 2006, and Buford Furrow’s murderous August 1999 invasion of a Los Angeles Jewish day-care center were all committed by adults. They had no connection to the schools other than being drawn to the soft target a school offers such psychopaths.

This latest shooting comes only a few weeks after the American Medical Association released a theme issue of its journal Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. This issue is dedicated to analyzing the April 2007 Virginia Tech shootings, in which 32 people were murdered. The authors are university officials, trauma surgeons, and legal analysts who pore over the details of the incident, looking for “warning signs” and “risk factors” for violence. They rehash all the tired rhetoric of bureaucrats and public-health wonks, including the public-health mantra of the 1990s that guns are the root cause of violence.

Sheldon Greenberg, a dean at Johns Hopkins, offers this gem: “Reinforce a ’no weapons’ policy and, when violated, enforce it quickly, to include expulsion. Parents should be made aware of the policy. Officials should dispel the politically driven notion that armed students could eliminate an active shooter” (emphasis added). Greenberg apparently isn’t aware that at the Appalachian School of Law in 2002 another homicidal Virginia student was stopped from shooting more of his classmates when another student held him at gunpoint. The Pearl High School murderer Luke Woodham was stopped cold when vice principal Joel Myrick got his Colt .45 handgun out of his truck and pointed it at the young killer.

Virginia Tech’s 2005 no-guns-on-campus policy was an abject failure at deterring Cho Seung-Hui. Greenberg’s audacity in ignoring the obvious is typical of arrogant school officials. What the AMA journal authors studiously avoid are on one hand the repeated failures of such feel-good steps as no-gun policies, and on the other hand the demonstrated success of armed first responders. These responders would be the students themselves, such as the trained and licensed law student, or their similarly qualified teachers.

“Virginia Tech’s . . . no-guns-on-campus policy was an abject failure.”

In Cleveland this week and at Virginia Tech the shooters took time to walk the halls, searching out victims in several rooms, and then shooting them. Virginia Chief Medical Examiner Marcella Fierro describes the locations of the dead in Virginia Tech’s Norris Hall. Dead victims were found in groups ranging from 1 to 13, scattered throughout 4 rooms and a stairwell. If any one of the victims had, like the Appalachian School of Law student, used armed force to stop Cho, lives could have been saved.

The people of Virginia actually had a chance to implement such a plan last year. House Bill 1572 was introduced in the legislature to extend the state’s concealed-carry provisions to college campuses. But the bill died in committee, opposed by the usual naysayers, including the Virginia Association of Chiefs of Police and the university itself. Virginia Tech spokesman Larry Hincker was quoted in the Roanoke Times as saying, “I’m sure the university community is appreciative of the General Assembly’s actions because this will help parents, students, faculty, and visitors feel safe on our campus.”

It is encouraging that college students themselves have a much better grasp on reality than their politically correct elders. During the week of October 22—26 Students for Concealed Carry on Campus will stage a nationwide “empty holster” demonstration (peaceful, of course) in support of their cause.

School officials typically base violence-prevention policies on irrational fears more than real-world analysis of what works. But which is more horrible, the massacre that timid bureaucrats fear might happen when a few good guys (and gals) carry guns on campus, or the one that actually did happen despite Virginia Tech’s progressive violence-prevention policy? Can there really be any more debate?

AMA journal editor James J. James, M.D., offers up this nostrum:

We must meaningfully embrace all of the varied disciplines contributing to preparedness and response and be more willing to be guided and informed by the full spectrum of research methodologies, including not only the rigid application of the traditional scientific method and epidemiological and social science applications but also the incorporation of observational/empirical findings, as necessary, in the absence of more objective data.

Got that?

I prefer the remedy prescribed by self-defense guru Massad Ayoob. When good people find themselves in what he calls “the dark place,” confronted by the imminent terror of a gun-wielding homicidal maniac, the picture becomes clear. Policies won’t help. Another federal gun law won’t help. The only solution is a prepared and brave defender with the proper lifesaving tool—a gun.

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

1. According to Wheeler, what is “depressingly similar” about the mass murders committed on campuses (para. 2)?

2. What is Wheeler’s attitude toward those who said that “guns are the root cause of violence” (3)? How can you tell?

3. Why, according to Wheeler, do college administrators and bureaucrats continue to ignore the answer to the problem of violence on campus? How does he refute their objections?

4. Do you find Wheeler’s argument in support of his thesis convincing? What, if anything, do you think he could have added to strengthen his argument?

5. How does Wheeler’s language reveal his attitude toward his subject? (For example, consider his use of “gem” in paragraph 4 and “politically correct” in paragraph 8.) Can you give other examples of language that conveys his point of view?

6. How do you think Wheeler would respond to the ideas in “Warning Signs: How You Can Help Prevent Campus Violence” (p. 554)? Which suggestions do you think he would support? Which would he be likely to oppose? Explain.

THE FEAR INDUSTRY GOES BACK TO SCHOOL

SASHA ABRAMSKY

This piece was published in The Nation on August 29, 2016.

“Security was the number-one factor for me in choosing a school,” explained one of the mothers I met late last winter at a Montessori preschool in an affluent suburb of Salt Lake City. A quality-control expert at a dietary-supplement company, the woman said she vividly remembers the jolt of horror she felt when she first learned of the Columbine massacre in 1999. So when the time came to send her child to preschool, she selected one that markets itself not only as creative, caring, and nurturing, but also as particularly security-conscious.

To get the front door of the school to open, visitors had to be positively ID’d by a fingerprint-recognition system. In the foyer, a bank of monitors showed a live feed of the activity in every classroom. After drop-off, many parents would spend 15 minutes to half an hour staring at the screens, making sure their children were being treated well by their teachers and classmates. Many of the moms and dads had requested internet access to the images, but the school had balked, fearing that online sexual predators would be able to hack into the video stream. All of the classroom doors had state-of-the-art lockdown features, and all of the teachers had access to long-distance bee spray—which, in the case of an emergency, they were instructed to fi re off at the eyes of intruders. The playground was surrounded by a high concrete wall, which crimped the kids’ views of the majestic Wasatch Mountains. The imposing front walls, facing out onto a busy road, were similarly designed to stop predators from peering into the classrooms.

“I fear a gunman walking into my child’s school and gunning up the place,” the mother continued. (I have withheld her name, and that of the school, upon request.) “And I fear someone walking onto the playground and swiping a kid. And I fear an employee of the school damaging my child. These things happen more commonly than people expect.”

Actually, they don’t. Despite the excruciating angst suffered by this woman and so many other parents, school violence is a rarity in America. According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), 34 children in the United States were murdered while in school during the 1992—93 school year. From 2008 to 2013, the most recent years for which the NCES provides data, the average annual figure was 19. In recent decades, the numbers have waxed and waned, hitting 34 again in 1997—98 and going as low as 11 in 2010—11. Generally, the trend has been downward.

If one adds the deaths of teachers and other staff, as well as suicides by students during the school day, the numbers go up, of course. In the 20-year period covered by the NCES data, 2006—7 was the deadliest, with 63 violent deaths occurring in America’s schools. That is unquestionably 63 too many violent deaths, and for the families directly affected by the killings, it represents unfathomable—and inextinguishable—anguish.

But it isn’t quite the national epidemic that one might picture based on the vast media coverage these killings receive. In fact, far more children and young adults are killed on the impoverished streets of America’s large cities every year. By several orders of magnitude, far more kids die each year in car crashes or drowning accidents—or from asthma. And far more young lives are lost to a host of other diseases closely correlated with poverty.

There are approximately 55 million K—12 students in America and roughly 3.5 million adults employed as teachers. There are, in addition, millions of support staff—janitors, nurses, cooks, after-school-program providers, and so on. Even in the deadliest years, the chance of a student or adult being killed at school is roughly one in a million. By contrast, roughly five out of every 100,000 American residents are murdered each year. Extrapolating from this, schools are somewhere in the region of 50 times safer than society overall.

And yet you’d never know that from the level of fear that exists around schools—or from the vast amount of money we spend attempting to make them more secure. The research company IHS Technology recently estimated that schools and universities spent about $768 million on security measures in 2014—a sum that it predicted would rise to roughly $907 million for 2016. That’s an awful lot of money to spend at a time when state and local budget cuts are limiting educational opportunities for students across the country.

The spike in spending on school security began in the mid-1990s, when the Clinton administration, seeking to co-opt the prevailing tough-on-crime, zero-tolerance message, pushed an array of measures that led to the hiring of several thousand new “school resource officers.” Thousands more police officers were funded by state and city grants, making the presence of armed police a daily reality in schools around the country. At the same time, one school after another, especially in inner cities, brought in airport-style metal detectors and introduced “clear bag” policies so that school officials could easily check everything students brought into the building.

As schools came to resemble prisons—which, perhaps not coincidentally, were also expanding during these years—an increasing number of students ended up being arrested on school grounds. In cities like Stockton, California, where even nonpolice “resource officers” are granted arrest powers, thousands of kids have acquired criminal records for minor offenses. Students in these districts are arrested at rates far higher than those reported in places where resource officers aren’t given such powers. The construction of this “school-to-prison pipeline” has disproportionately affected minority students—who, in turn, face harsher penalties once they come into contact with the criminal-justice system. Sometimes the confrontations with security officers can be horrendous. Last October, for example, students in a South Carolina school filmed an officer violently dumping a teenage girl out of her chair and dragging her across the floor before arresting her—all because she used her cell phone during math class.

In recent years, the school-security industry has expanded to include high-tech surveillance among its offerings. The school district in Las Vegas has been installing surveillance cameras in schools since 2000, and they are now standard in new schools. All told, according to a 2014 article in the Las Vegas Sun, more than 12,000 surveillance cameras are recording in Sin City’s schools, complementing the hundreds of cameras in school buses and on major thoroughfares, and the tens of thousands of cameras in the city’s giant casinos. The Sun didn’t report on how much this system cost, but a much smaller project at St. Mary’s High School in St. Louis reportedly cost the school $500 a month to lease two cameras, or $15,000 to buy them outright.

Newark Memorial High School, in the San Francisco Bay Area, has embedded ShotSpotter technology, an advanced sound-recognition sensor system deployed by police departments in many urban neighborhoods to identify when and where gunshots are occurring. Although the school hasn’t had to pay ShotSpotter for the technology—the company views it as a testing ground for how such a system could be used in a school setting—police departments around the country pay anywhere from $65,000 to $90,000 per year for each square mile covered by the sensors.

And then there’s the Indianapolis suburb of Shelbyville, where school superintendent Paula Maurer recently became so worried about the possibility of a shooting that she installed a $400,000 security system in the town’s high school. The entire campus, located in open countryside just outside of town, is now saturated with cameras linked into the nearest police station. Every teacher wears a panic button around his or her neck, and pressing it sends the entire campus into instant lockdown. For good measure, police officers watching from miles away can set off blinding smoke cannons and ear-splitting sirens at a moment’s notice.

“Lately, America’s school-security fetish has reached a whole new level of bizarre.”

Much as anticrime advocates convinced government agencies in the 1990s and 2000s to fund an increasing array of punitive programs, today school-security companies and trade associations are lobbying legislators in several states to change building codes so that schools will be mandated to spend more on their security systems. If they get their way, the Shelbyville experiment could well be a harbinger of things to come.

Lately, America’s school-security fetish has reached a whole new level of bizarre. In the wake of the December 2012 Sandy Hook massacre in Newtown, Connecticut, one company after another has rushed to take advantage of the opportunities presented by the epidemic of fear that emerged in response to school violence, and to exploit the emotional vulnerabilities of terrified parents. As a result, a huge number of utterly inane products have entered the market.

School-security specialist Kenneth Trump, longtime president of the Cleveland-based National School Safety and Security Services, likens the surge of “overnight experts, gadgets, and gurus who have popped up out of the blue” to a feeding frenzy. “Every time we have a high-profile shooting, we see another business or product, well intended but not well thought out,” he says. After the Columbine massacre, Trump recalls, there was a “fairly reasonable conversation” about security. By contrast, in the years since the slaughter at Sandy Hook, “it’s been the worst I’ve seen in 30-plus years, in terms of people responding emotionally and businesses preying on the emotions of people who are afraid.”

Take, for example, Bullet Blockers, a company working out of Lowell, Massachusetts, that manufactures bulletproof backpacks for elementary-school children. The ones for young girls come in raspberry pink or red plaid; the ones for boys come in red, black, navy blue, and more. The company also markets bulletproof jackets, bulletproof iPad cases, and bulletproof whiteboards for use in classrooms. It even sells a “survival pack and safety kit,” complete with fire starters, first-aid guides, cold compresses, and other items that would allow a child to survive a prolonged school lockdown.

Bullet Blockers CEO Ed Burke won’t divulge how many items his company has sold, but he does say that “since the Paris attacks [of November 13, 2015], our business has grown 80 percent and continues to grow.” Have his products actually saved lives? “Thank God, none as yet,” he answers—meaning that none of his products have thus far been used to foil an attacker in a school shooting. But “they’ve been tested randomly, to test ballistic capabilities.”

None of Burke’s clients would agree to talk for this article, but Burke does aver that his company sold products to “a grandmother who lives in Sandy Hook, who got her grandchildren a couple of backpacks.” He adds, “I got a phone call from a gentleman in California whose wife was involved in the massacre in San Bernardino. She was in the building. He wanted to get her a backpack.” Burke also cited a family that ordered a man’s farm coat, a woman’s leather coat, a child’s nylon jacket, and three backpacks, all bulletproof as well.

In Hauppauge, New York, Derek Peterson runs a tech start-up called Digital Fly, which enables school officials to monitor all social-media postings within a radius chosen by the school. The intent, which would be eerily familiar to government spy agencies the world over, is to drill down into communications used near schools as a way to identify potential shooters, bombers, bullies, or would-be suicides. The postings of everyone within that catchment area—whether they’re students, local residents, or simply people passing through—are monitored. “My software will identify it,” Peterson enthuses, seemingly oblivious of (or indifferent to) the extraordinary privacy implications of his work. “The school administrator will get emails. At that point, every school has a different policy—they get the parents, the police involved. I provide you with a hammer: Here’s the tools to build the house.”

Peterson claims that his system is being used in more than 50 schools around the country, as well as some in Ireland and South Africa. His ambitions are large. “It could go global,” he says. “We’re hoping it does. I’m a serial entrepreneur; this is right in my sweet spot. How do you put a price on protecting little ones? Unfortunately, we live in a crazy world where kids are targeted. So any way we can protect children, I’m all for it.”

Much like Burke, Peterson acknowledges that he has no real way of knowing if Digital Fly is working—although he does claim that it helped prevent two suicides in New York City schools. But since he charges only $1.50 to $2.75 per student, Peterson hopes that schools will decide it’s worth adding to their tool kit just on the off chance it works. He tells parents at PTA meetings that his service costs the equivalent of one can of soda per year for each kid, and then adds a spiel about how, if even one bloody nose is avoided, it will be money well spent. “Right now, there are 50 million K—12 matriculating students just in the U.S.,” Peterson says as he ponders his company’s future. “The sky is the limit.”

Many experts worry that the new school-security measures can endanger the people they’re supposed to protect. Anti-intruder doors were installed in some schools in Ohio without overrides built in, making it hard for first responders to reach stranded kids in the event of a crisis. There is some anecdotal evidence that lockdown drills injure teachers; they have reputedly resulted in a flurry of workers’-compensation claims across the country. And at the Kaimuki Middle School in Honolulu, a lockdown drill in which a teacher ran through the school wielding a hammer and playing an attacker drew criticism after several young children were traumatized by the sight of their seemingly crazed teacher on a rampage.

The increasing cost of high-tech safety measures has become a concern too. At a time when many schools can’t rustle up enough money to keep art and music classes running, and when parents are often asked to purchase such necessities as notebooks, pencils, and even toilet paper, all of this militarization and surveillance represents a scandalous diversion of education funds.

Shelbyville’s $400,000 security system, for example, could have been used to pay the salaries and benefits of roughly eight full-time teachers for a year (the average salary for a teacher in the town is $43,000). That’s not an insignificant fact in a city that shed five teachers in April 2010 as a way of saving $250,000 during the dog days of the recession. All told, according to the Indiana Economic Digest, Shelbyville schools lost access to over $1 million that year. Three years later, the school district cut the hours for scores of teaching aides, bus drivers, and other staff to avoid the cost of covering their health insurance under the terms of the Affordable Care Act.

Ronald Stephens, the executive director of the California-based National School Safety Center, who teaches a graduate course on school-safety issues at Pepperdine University, recalls talking with the superintendent of a school near his home in Oak Park, one of Los Angeles’s many affluent suburbs. The superintendent explained that he was under tremendous public pressure to put security fences around the district’s schools, at a cost of $1.6 million. He was resisting it because he believed the schools had bigger needs: The teachers hadn’t received a pay raise in five years.

Back at the Montessori school in Utah, I met a father in his mid-40s who bemoaned the fact that kids could no longer roam freely, walking to and from school alone, playing unsupervised outdoors for hours with their friends, as he’d done growing up in the Bay Area. “Times are different now,” he explained sadly. “There are more crazy people in the world.”

The man, who worked for a large plumbing and air-conditioning company, had a bachelor’s degree in criminal-justice studies. Intellectually, he knew the statistics. He knew that violent-crime rates were higher when he was growing up than they are today. So I asked him if he was sure that the environment was less safe for his 17-year-old daughter than it had been for him. “Probably not,” he said after a long pause. “It’s hard. She is way too sheltered. I’d love to let her spread her wings a little bit more. But we do keep our thumbs on her. There’s always the fear of a kidnap, a traffic accident. Turn on the news at night—we watch the news while we eat dinner. The media loves to create a sense of panic. They love bad news.”

On one level, he knew that the media were selling him a bill of goods. But he couldn’t bring himself to turn away—and the more he watched, the more fearful he became. The man told me that he’s had nightmares about mass shootings and kidnappings; his face got beet red with tension even while discussing it.

Unfortunately, this is the sort of circular reasoning that our society is increasingly trapped in when it comes to raising and educating our children. Television, newspapers, and social media focus on sensational but statistically anomalous horror stories about school violence. Parents and the broader community work themselves into a panic, prompting politicians to vow that they will do “whatever it takes” to make everyone safer. Security technologies emerge to fill the perceived need for stronger safety measures, and schools end up spending money they don’t necessarily have to implement solutions they almost certainly will never need. The presence and the media coverage of these heightened security measures increase the public’s sense of fear, and the spiral descends even further.

“We’re preparing for the 1,000-year flood,” says Ronald Stephens. “Children are safer at school than anywhere else.”

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

1. At what point in his essay does Abramsky state his thesis? Why do you think he states it where he does?

2. Does Abramsky structure his argument inductively or deductively? What is the advantage of his organization? Are there any disadvantages? Explain.

3. Abramsky begins his essay with several anecdotes. What point does he make with them? Why do you think he chose to begin his essay in this way?

4. According to Abramsky, what misconception about school shootings do many parents and school administrators have? How effectively does he address these misconceptions?

5. What kind of evidence does Abramsky provide to support his thesis? Does he provide enough evidence? Should he have provided other types of evidence? Explain.

6. Both Ed Burke (para. 18) and Derek Peterson (22) concede that they don’t know for sure if their products actually work. How are they able to convince parents and school officials to purchase them? Do you find their explanations convincing?

7. In his conclusion, Abramsky quotes Ronald Stephens, the executive director of the National School Safety Center, who says about heightened security measures at school, “We’re preparing for the 1,000-year flood” (31). What does he mean?

8. What ethical dilemma do parents and administrators face concerning spending on school security? If you were a parent at a school considering state-of-the-art surveillance, what would you advise school administrators to do?

I’M A SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST—AND I THINK TEACHERS SHOULD BE ARMED

MICHAEL W. GOLDBERG

The Nation published this article on August 29, 2016.

I’ve been a school psychologist for the past 20 years. In the wake of the school shootings in Florida, I am brought right back to December 7, 2017, the day of the deadly mass shooting at the high school I currently serve. In the aftermath, I helped to counsel students through the trauma caused by direct exposure to a murderous terrorist act—including nightmares, uncontrollable and unpredictable floods of tears, senseless “what if” questions, anxious obsessing, and survivors’ guilt.

I also have a unique perspective on the school shooting problem, having been both a mental health professional and a licensed concealed firearm carrier for the past 24 years.

In addition to zero bullying tolerance, empathy building, and lockdown drills in our schools, we must bolster our self-defense. Specifically, law-abiding, psychologically stable, specially trained staff should carry concealed weapons.

This would reduce our students’ trauma and has the potential to stop terror immediately—or deter it from occurring in the first place.

A Centers for Disease Control study commissioned by President Obama, “Priorities for Research to Reduce the Threat of Firearm-Related Violence,” supports this idea. The report concludes that “self-defense can be an important crime deterrent”:

Studies that directly assessed the effect of actual defensive uses of guns (i.e., incidents in which a gun was “used” by the crime victim in the sense of attacking or threatening an offender) have found consistently lower injury rates among gun-using crime victims compared with victims who used other self-protective strategies.