Practical argument: A text and anthology - Laurie G. Kirszner, Stephen R. Mandell 2019

Debate: Should the United States Establish a Universal Basic Income?

Debates, casebooks, and classic arguments

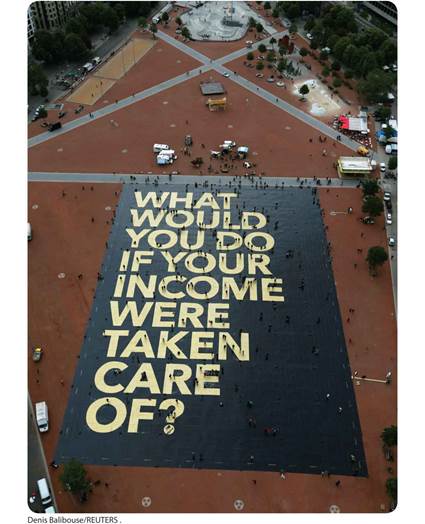

This giant poster was created by a Swiss nonprofit in support of a campaign to institute Universal Basic Income.

As George Zarkadakis points out in the essay that begins on page 636, the idea of a universal basic income (UBI) has a long history, proposed as early as 1516 in Utopia, a work of satirical fiction by the author, humanist, and Catholic saint Thomas More (1478—1535). In the nineteenth century, political economists and philosophers, such as John Stuart Mill, suggested that an equal sum of money be given to all members of the community to guarantee their basic subsistence. As the modern welfare state evolved in the twentieth century, various economists and policy makers refined and adapted the idea. In some cases, as in the United States, a form of guaranteed income was integrated into social insurance programs, such as Social Security, which pays benefits to the disabled, the elderly, and others. More direct and universal forms of UBI have also been proposed over the years. As the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) asserts: “The idea of an unconditional basic income is quite simple: every legal resident in a country receives a monthly stipend sufficient to live above the poverty line. Let’s call this the ’no frills culturally respectable standard of living.’ ”

In the United States, discussion and advocacy of such programs waned in the 1980s and 1990s, but the twenty-first century is bringing new challenges that have led to a revival of interest in UBI. Many believe that automation will eliminate large sectors of the workforce in the future, as robotics already have in many fields. For these observers and policy makers, the UBI could ease some of the economic and social effects of high unemployment. For others, UBI is a practical solution to economic inequality and instability in the face of growing disparities between the wealthy and everyone else. Not surprisingly, proposals for a universal guaranteed income raise questions, problems, and criticisms: Who will pay for it? Would such a policy lead to wholesale welfare dependence—and create incentives for people not to work? How would it reshape our economy and our politics?

The following two essays provide views of this issue from two revealing angles. In “A Conservative Case for Universal Basic Income,” Canadian writer Christian Bot argues that UBI, a policy generally associated with the economic and political left, may actually help maintain conservative social and cultural values, such as the preservation of the nuclear family. In contrast, science writer and artificial intelligence engineer George Zarkadakis makes a comprehensive case against UBI, arguing that it could lead to “an era of corporatist totalitarianism dressed up as representative democracy.”

A CONSERVATIVE CASE FOR UNIVERSAL BASIC INCOME

CHRISTIAN BOT

This essay was published in Areo Magazine on August 2, 2018.

It hardly came as a surprise when the National Review, a leading American conservative publication, rushed to assail the idea of universal basic income (UBI for short) with its usual vigor, from almost its very first mention. The men and women manning the fort at the Review—most of whom are superlative, highly intelligent writers—have remained steadfast in their defense of quasi-libertarian free-market economics against the rising tide of Donald Trump’s economic nationalism. It is of course within their rights to do so, and their principled persistence in an increasingly unpopular doctrine earns my commendation to some extent. But I feel they are mistaken.

But, first of all, what actually is UBI? There have been widely varying proposals, but the essential idea is to provide every citizen of a given jurisdiction with an unconditional sum of money at regular intervals. Its proponents typically insist that, if implemented, it will reduce poverty and income inequality, strengthen the economy by boosting consumer spending, and offer protection from the disruptive effects of workplace automation. The latter will become especially resonant in the coming years, as automation siphons off ever more jobs. But, as the National Review shows, it has been an uphill battle to convince many conservatives of the idea’s viability or even its desirability. There is a critical element to this debate, however, that has thus far been almost entirely overlooked. UBI has the power to not only preserve the traditional nuclear family, but to raise its vitality and prestige to levels not seen in many years. As such, it ought to spur conservatives to see beyond their stubborn economic doctrines and acquaint themselves with the conservative case for UBI.

UBI is in essence a radical form of social welfare. But conservatives take a gross misstep when they jump to the conclusion that UBI must therefore be an inherently left-wing idea. It is easy to see why this misconception has been allowed to spread. The very thought of showering individuals with unconditional money, regardless of their work situation, sets off alarm bells for fiscal conservatives, who find any initiative of this sort repellent. But the prime beneficiaries of UBI would be those permanently out of work thanks to automation. Conservatives have long professed sympathy with the “deserving” down-and-outs, and compassion, in any case, is not a monopoly of the left. Conservatives must reject being tethered to a callous and heartless individualism in a perverse race to the bottom to win the posthumous approval of Ayn Rand and her ilk. UBI is no more inherently left wing than salsa dancing is the domain of the right. Conservatives would be wise to step forward and discuss this very important and timely proposal. The image of the cold-hearted conservative need not reflect reality.

Nevertheless, conservative economic thought is stuck in neutral, owing in large part to conservatives’ unqualified support for laissez-faire capitalism. Little do they realize that capitalism has played a fundamental role in destabilizing the nuclear family—not only by leaving the poor, the struggling, and the destitute to fend for themselves without social assistance, but also by utterly alienating labor from the moral development of the worker. To better understand this, we must go far back in history and explore the changing nature of labor. I do not idealize the Middle Ages, but the undercurrent of religion that propped up so many areas of medieval life applied to labor too. The typical tradesman of, say, a Belgian town in around 1300 toiled under the understanding that his work was first and foremost a labor of love for God, and only secondarily a means, however necessary, of subsistence. This view was dealt a fatal blow by the Reformation, which shattered the socially cohesive power of the Catholic Church in precisely those areas of Northern Europe that soon began to embark on their mercantile ascendancy. When these regions industrialized in the nineteenth century, the uprooted workers, predictably, found no significant moral or political recourse to mitigate the horror of their plight.

The European nations in which the capitalist alienation of labor proceeded apace remained avowedly Christian. Paradoxically, it was the avowedly atheist Karl Marx who raised his voice more loudly than most against this outgrowth of unrestrained capitalism. Marx was quite explicitly an enemy of the traditional nuclear family. In The Communist Manifesto, he trumpeted wife-swapping and the abolition of the family, which he denigrated as a tool for the bourgeois domination of society. But he also observed that the ravages of mid-nineteenth-century capitalism were tearing families apart, through demoralizing overwork and abysmally low wages. In the Soviet Union under Lenin, abortion and divorce were legalized, with the predictable outcome of a declining birthrate. Lenin’s successor Stalin, genocidal thug though he was, saw the writing on the wall and undid much of his forebear’s radical work, notably by prohibiting abortion in most cases. There is more than a hint of the absurd at play when more can be said—at least nominally—for a mass-murdering communist dictator than for twenty-first century conservatives, who evince support for the nuclear family, but steadfastly refuse to take the necessary economic steps to protect it. The overwhelming hypocrisy of it all not only lets down struggling families but erodes their trust in the conservatives who are supposed to be helping them.

The precise channels by which economic strain lends itself to family breakdown are varied and manifold, but the basic principle deserves some elucidation. Most people reading this can relate to the stress produced by the threat of economic hardship, perhaps even of insolvency and poverty. I emphasize threat, because the very fear of it often suffices to send whole families into free-fall, as surely as the mere whisper of financial catastrophe can throw Wall Street into an eight-hour terror. The modern mind prizes security above almost all else, but, paradoxically, capitalism in its current incarnation refuses most stubbornly to offer any meaningful measure of it to vast swaths of the population. The zeitgeist of the early twenty-first century demands that we ensure a certain level of material security, before we can even begin to discuss preserving the nuclear family. UBI will not, in itself, restore the idealistic medieval conception of labor, but—by alleviating millions of families’ gnawing fears of poverty—it will make that conversation possible.

“The precise channels by which economic strain lends itself to family breakdown are varied and manifold.”

Conservatives, to their credit, have little problem detecting the deplorable social outcomes of the family breakdown that they abhor. It is almost a truism among conservatives that children who emerge from broken and dysfunctional homes are at considerable risk of future delinquency, drug and alcohol abuse, and low educational achievement. They represent vast sums of sunk costs for the state, which most commonly takes the form of the inevitable welfare, disability, and unemployment payments that proportionately far too many of them will eventually draw upon. This is only one part of the story. The other includes medical costs stemming from substance abuse and its concomitant health problems—above all in countries that have socialized medicine, such as my native Canada—and the cost of law enforcement and detention, should they spend time in juvenile facilities or, later on in prison. All this money could have obviously been better spent elsewhere were it not so tragically necessary here. What, then, do we have to lose from an ambitious UBI scheme, laser focused on keeping families together and economically secure? We cannot know for sure at this early stage, but it seems likely that the cost of most mainstream UBI proposals will fall well short of the expense of mopping up the mess attributable to broken families.

Some have already hinted at the material basis needed to keep families happy and secure. According to an apocryphal account, St. Thomas Aquinas believed that a pious soul suddenly plunged into the throes of spiritual sorrow ought to seek out a warm bath, a sleep, and a glass of wine. Authentic or otherwise, this attests to the necessity of possessing some degree of material security before you can even begin to think about the moral realm. One may take issue with scholasticism’s habit of compounding virtually everything into a system of hierarchies, but the practice is eminently valid here. There exists a definite hierarchy of needs in asymmetrical relation to one another. At its base are man’s material imperatives, and above these are his moral needs. One may be getting along quite well in the material sense while remaining morally dead, but the inverse is not equally true. This is much like saying that a tower without a foundation is doomed to collapse under its own weight, or that a pizza without toppings is still a pizza, but toppings without dough are not. To continue the culinary metaphor, conservatives never tire of insisting on the centrality of the masculine “breadwinner” figure. They ought to consider whether a family whose breadwinner is out of a job, and staring poverty in the face, can realistically tend to his and his family’s moral growth. UBI, if implemented with commensurately pious intentions, can restore the foundation to the collapsing tower and become a force not only for newfound material abundance, but for moral excellence as well.

In a similar vein, there is more than a germ of truth to the old adage, “a family that prays together stays together.” Try as they might to deny the relevance of the moral realm, hardened atheists and agnostics would do well to take note of the objective benefits attached to personal spirituality, at both the individual and domestic levels. As the Institute for Family Studies observes, “Family prayer time is quality time together, time not spent in front of the television or a smartphone, but rather, time spent communicating on a deeply personal level.” Individual prayer, too, is linked to “reduced stress, increased self-awareness, better communication, and a more empathetic and forgiving attitude towards others.” It does not require a systematic and theological belief in God to appreciate the positive effects of prayer or of cultivating one’s spiritual and moral development more broadly. This is scarcely possible in an atmosphere of squalor and perpetual economic insecurity. If conservatives wish to back up their appeals for more widespread religious commitment, there are few better ways to do so than by providing material peace of mind to those who desperately need it.

UBI is something that we are probably going to hear a lot more about in the near future. The growing impact of automation will ensure that. But, just as economic libertarians are bound to put up a spirited fight against it, conservatives must be ready to vigorously defend it. There is a compelling conservative case to be made in its favor. I sense that a paradigm shift is coming in the age-old spat between liberals and conservatives, one in which conservatives will leave behind the doctrines of economic inaction inherited from a bygone age. The debate surrounding UBI offers an ideal stage on which to prove conservatives’ commitment not only to the humanitarian values of social welfare and compassion, but also to the preservation, strengthening, and promotion of the traditional nuclear family. For far too long, conservatives have tolerated an appalling gap between their words and their deeds. If the conservative movement wishes to prove its enduring fealty to its rhetoric, that gap must now close.

![]() READING ARGUMENTS

READING ARGUMENTS

1. How does Bot characterize conservative opposition to universal basic income in his opening paragraph? What does this characterization suggest about his purpose and audience?

2. What does Bot accomplish with his use of definition in paragraph 3?

3. Bot identifies a number of cause-and-effect relationships. What point is he trying to make (or support) with this causal connection?

4. What “hypocrisy” does Bot identify in paragraph 5?

5. Bot believes that in the future, more people will be out of work. What key cause of future unemployment does he identify? How does he believe universal basic income would address this problem? Do you see this as a practical solution? Why or why not?

THE CASE AGAINST UNIVERSAL BASIC INCOME

GEORGE ZARKADAKIS

This essay was first published on the Huffington Post website on February 24, 2017.

Universal Basic Income (UBI) suggests that all adults should receive the same minimum, guaranteed, income from the State irrespective of their other incomes. It is being put forward as the “solution” to the obliteration of jobs due to robots, artificial intelligence, and machine learning. In a future, when work will be intermittent or absent, UBI could provide safety net and replace the current, complex welfare systems—or so its advocates claim.

UBI is not a novel idea. Thomas Paine first proposed it in the late 19th century, when he suggested that big landowners should be taxed and the dividends redistributed to every young man in America. Paine’s economic argument rested on the idea of “rent”: the owners of producing assets gain from the work of those who use these assets to produce goods and services. This gain is a rent because the owners do not participate in production. It is rather significant that the business models of the big high-tech companies in the modern digital economy are founded on rent. Think of digital platforms, or the cloud, or XaaS (“everything as a service”) models. In a highly automated economy the owners of the automating technology will be akin to the Paine’s big landowners. So why not tax them and redistribute the money to the rest of us?

There are several arguments against this, and I would like to separate them in three categories: economic, political, and ethical. Let’s start with economics. In a globalized economy capital is free to move to the lowest cost. In the absence of a world government that can enforce a tax regime on every country, the practicality of taxing the cash reserves of fully automated companies—as suggested by Thomas Piketty among others—is a moot point. Besides, such a tax would impact on those companies’ ability to invest and innovate, which could result in losing their competitiveness. In such a scenario companies operating from low or zero tax regimes would win. By curbing innovation in their jurisdictions governments of today’s advanced economies will also lose from the productivity dividend that automation is expected to deliver. Accordingly to a recent report by Accenture and Frontier Economics intelligent machines will raise the annual growth rate of gross value added (a close approximation of GDP) by 4.6 percent in US, 3.9 percent in UK, and 2.7 percent in Japan. Governments may like UBI because it is the sword that can cut through the messy Gordian knot of their welfare systems, which are generating generational poverty rather than helping anyone. But going for UBI may have adverse effects both on tax receipts as well as in losing the battle of the fourth industrial revolution to low tax competitors.

Politics comes into play as well. It is curious that big high-tech companies in Silicon Valley are such fervent supporters of UBI. Perhaps they are fearful of replacing the bankers as the most-hated capitalist villains, or maybe they want to pass the bucket to governments and relieve themselves of the responsibility of destroying the livelihoods of many.

“Quality of life requires a new way of thinking about work, not government handouts.”

Nevertheless, many of those companies would be happy to contribute some of their vast wealth to fund UBI, for this will allow them to have much greater leverage on government decisions. There has been a tug of war between high-tech companies and energy companies for who will have the greatest influence over government—for quite a while—and UBI seems to be fast becoming the new front line. While Bill Gates suggests a “robot tax” and Elon Musk advocates UBI, a conservative think tank led by notable republicans such as James Baker and Henry Paulson suggested a carbon tax for financing basic income. If you think that that the so-called “free-economy” is a euphemism for crony capitalism, wait till the automation era kicks in! But the deeper collusion of governments and capital can only lead to the further alienation of citizens. We are on the cusp of a citizen rebellion across the developed world. It would be foolhardy to suggest that, somehow, citizens will be quelled by UBI to the extent that they relinquished their rights, privacy, and well-being to decisions made behind closed doors between politicians and high tech, or energy, executives. Also, when we think of UBI we must ask ourselves: do we want to become financially dependent on the State? Especially on a State that is itself financially dependent on the owners of automation technologies?

Finally, there are many ethical problems with UBI. Quality of life is often ignored in the current discussion. There are millions of people currently on benefits whose life is miserable. Extending the idea of welfare to all under the guise of UBI we are in danger of extending misery. There are certainly many who would prefer to live poorly, as long as they do not have to get up in the morning and do any work. To them UBI will be just some extra cash to spend on life’s little luxuries. But most people need to feel valued and productive, to live meaningful lives, to support and nourish loving families, to be creative and develop their full potential. For them a life of idleness on borderline poverty, paid by taxing others who will be enjoying riches beyond imagination, does not seem like a desirable future. Quality of life requires a new way of thinking about work, not government handouts so we can stay home and play videogames all day.

So if not UBI then what? How should we manage the transition to a post-work future? There is too much hype about what AI can really do, and big questions regarding how companies will adopt these new technologies in practice. But if for the sake of simplicity we assume that most jobs will become obsolete by mid 21st century, then we ought to go back to the basics, rather than patching up what has gone wrong with welfare. And the basics include defining the role of citizens in a democratic society as the creators of wealth and prosperity. Democracy is based on the assumption that citizens are the producers of wealth and the owners of property. UBI is undermining the foundations of democracy because it transforms citizen freedom to citizen dependency. We must think beyond dependency, towards innovative systems where machine intelligence leverages our creativity and self-development on a bottom-up, rather than top-down, fashion. In short, we need to reinvent democracy in a post-work future. The alternative would be to enter an era of corporatist totalitarianism dressed up as representative democracy.

![]() READING ARGUMENTS

READING ARGUMENTS

1. Zarkadakis states that universal basic income is “not a novel idea” (para. 2). How does he support this claim?

2. According to Zarkadakis, arguments against universal basic income fall into three categories. What are they? How does he use these categories to structure his essay?

3. Zarkadakis notes that many high-tech companies support universal basic income. What does he suspect their motives are?

4. In Zarkadakis’s view, what ethical problems are associated with universal basic income? Do you agree with his assumptions about how people might respond to the policy?

![]()

AT ISSUE: SHOULD THE UNITED STATES ESTABLISH A UNIVERSAL BASIC INCOME?

1. Bot focuses on making an ideologically “conservative” case for universal basic income. In contrast, Zarkadakis avoids explicit labeling but considers three different aspects of the issue. Which approach seems more effective and persuasive to you? Why?

2. Both writers address moral and ethical questions in their essays, but from different angles. How do you think that Bot would respond to Zarkadakis’s ethical argument against universal basic income? Explain.

3. The two writers agree that automation, artificial intelligence, and robotics will lead to wider unemployment in the future. Do you agree with that assumption? Why or why not?

![]() WRITING ARGUMENTS: SHOULD THE UNITED STATES ESTABLISH A UNIVERSAL BASIC INCOME?

WRITING ARGUMENTS: SHOULD THE UNITED STATES ESTABLISH A UNIVERSAL BASIC INCOME?

After reading these two arguments, write an essay that argues either for or against establishing a universal basic income.