Practical argument: A text and anthology - Laurie G. Kirszner, Stephen R. Mandell 2019

Casebook: Does it pay to study the humanities?

Debates, casebooks, and classic arguments

At one time, students went to college to grow intellectually, to consider what they wanted to become, and to engage in the give-and-take of academic discourse. In the process, they could reexamine their ideas, develop new perspectives, and expand as thinkers and as human beings. Now, because students (and their parents) often have to take out loans to defray the high cost of tuition, they see a college education as an investment, not as a vehicle for intellectual growth. For this reason, they feel a great deal of pressure to ensure a return on their investment, and degrees in STEM subjects—an acronym that refers to courses in science, technology, engineering, and math—offer this return because STEM graduates earn more money than liberal arts majors. As a result, students flock to STEM majors in increasing numbers, and the humanities—art, literature, music, and history—become less and less important on college campuses. What good, students ask, is Michelangelo when it comes to developing a newer, better web app? How can an understanding of Tolstoy contribute to building a smarter smartphone?

Even though advocates for the humanities might concede that Tolstoy cannot help us to make a smartphone smarter, they would argue that all of us could benefit from reading Tolstoy. In addition, supporters of the humanities are concerned about what would be lost if we cut down on—or even eliminate—humanities courses. Although most people would agree that something is lost when we favor career skills over the humanities, they would have a difficult time pinpointing exactly what that “something” is. It is even harder to make the case for a liberal arts education when the average cost of a four-year degree is over $40,000 at a state school and over $135,000 at a private college.

In this chapter, you will read some essays that address the question of whether it pays to study the humanities. In “The Economic Case for Saving the Humanities,” Christina H. Paxson, the president of Brown University, makes the point that society will benefit if it actively supports the humanities. In “Major Differences: Why Undergraduate Majors Matter,” Anthony P. Carnevale and Michelle Melton argue that colleges have an obligation to give students the information they need to make intelligent decisions about their majors and their lives. In “Is It Time to Kill the Liberal Arts Degree?,” Kim Brooks questions whether colleges are downplaying the obstacles that liberal arts graduates face when they try to find full-time employment. Finally, in “Course Corrections,” Thomas Frank contends that in order to effectively defend the humanities, academics must first address the high cost of tuition.

THE ECONOMIC CASE FOR SAVING THE HUMANITIES

CHRISTINA H. PAXSON

Paxson’s essay was published on August 20, 2013, in the New Republic.

What can we do to make the case for the humanities? Unlike the STEM disciplines (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), they do not—on the surface—contribute to the national defense. It is difficult to measure, precisely, their effect on the GDP, or our employment rates, or the stock market.

And yet, we know in our bones that secular humanism is one of the greatest sources of strength we possess as a nation, and that we must protect the humanities if we are to retain that strength in the century ahead.

I do not exactly hail from the center of the humanities. I’m an economist, with a specialization in health and economic development. When you ask economists to weigh in on an issue, the chances are good that we will ultimately get around to a basic question: “Is it worth it?” Support for the humanities is more than worth it. It is essential.

We all know that there has been a fair amount of hostility to this idea recently in Congress and in State Houses around the country. Sometimes it almost feels as if there is a National Alliance against the Humanities. There are frequent potshots by radio commentators, and calls to reduce government spending in education and scholarship in the humanities.

It has become fashionable to attack government for being out of touch, bloated, and elitist; and humanities funding often strikes critics as an especially muddle-headed form of government spending. For that reason, the humanities are in danger of becoming even more of a punching bag than they already are.

In the current economic environment, these attacks have the potential to sway people. Any expenditure has to be clearly worth it. “Performance funding” links government support to disciplines that provide high numbers of jobs. Or, as in a Florida proposal that emerged last year, a “strategic” tuition structure would essentially charge more money to students who want to study the humanities and less money for those going into the STEM disciplines.

“Federal support for the humanities is heading in the wrong direction.”

As a result, there is grave cause for concern. Federal support for the humanities is heading in the wrong direction. In fiscal year 2013, the National Endowment for the Humanities was funded at $139 million, down $28.5 million from FY 2010, at a time when science funding stayed mostly intact. This is part of a pattern of long-term decline since the Reagan years.

I believe the question is fair. Are the humanities worth it? To push back against the recent tide of criticism, I’d like to offer several strategies.

First, we need to argue that there are real, tangible benefits to the humanistic disciplines—to the study of history, literature, art, theater, music, and languages. In the complex, globalized world we are moving toward, it will obviously benefit American undergraduates to know something of other civilizations, past and present. Any form of immersion in literary expression is helpful when we are learning to communicate and defend our thoughts. And it should not be that difficult to concur that a thorough and objective grounding in history is helpful and even inspiring when applying the lessons of our past to the future.

This point came home to me when, in my previous role as Dean of Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School, I went to the university archives to read the reports and correspondence that concerned the formation of the School in 1929. The founding director of the School, DeWitt Clinton Poole, wrote that the need was not for “young men minutely trained in specific technicalities” but, instead, for a “broad culture that will enlarge the individual’s mental scope to world dimensions.” Accordingly, the curriculum was designed to ground students in both the social sciences and the humanities. At that time—on the eve of the Great Depression—there was concern that such an “impractical” education would be of little value. Indeed, one alumnus wrote that the curriculum “is not immediately useful to the boy who has to earn a living.” Yet, if one looks back over the course of the school’s rich history, it is evident that many of the men and women who were exposed to that curriculum went on to positions of genuine leadership in the public and private sectors.

We know that one of the best aspects of the undergraduate experience is the fact that it is so multifaceted. Our scientists enjoy studying alongside our humanists and vice versa. They learn more that way, and they do better on each side of that not-very-precise divide. When I ask any of Brown’s business-leader alumni what they valued most during their years at Brown, I am just as likely to hear about an inspirational professor of classics or religion as a course in economics, science, or mathematics.

Second, we need to better defend an important principle that centuries of humanism have taught us—that we do not always know the future benefits of what we study and therefore should not rush to reject some forms of research as less deserving than others. In 1939, Abraham Flexner, the founding director of the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton, wrote an essay on this topic titled “The Usefulness of Useless Knowledge.” It was published in Harper’s in 1939, on the eve of World War II, a time when we can assume there was a high priority placed on military and scientific knowledge. In this essay, Flexner argued that most of our really significant discoveries have been made by “men and women who were driven not by the desire to be useful but merely the desire to satisfy their curiosity.”

Flexner’s essay underscores a very important idea—that random discoveries can be more important than the ones we think we are looking for, and that we should be wary of imposing standard criteria of costs and benefits on our scholars. Or perhaps I should put it more precisely: We should be prepared to accept that the value of certain studies may be difficult to measure and may not be clear for decades or even centuries.

After September 11, experts in Arabic and the history of Islam were suddenly in high demand—their years of research could not simply be invented overnight. Similarly, we know that regional leaders like Brazil, Indonesia, and South Africa will rise in relevance and connectivity to the United States over the next few decades, just as China and India already have. To be ready for those relationships, and to advance them, we need our humanists fully engaged.

And third, the pace of learning is moving so quickly that I would argue it is all the more important that we maintain support for the humanities, precisely to make sure that we remain grounded in our core values. As many previous generations have learned, innovations in science and technology are tremendously important. But they inevitably result in unintended consequences. Some new inventions, if only available to small numbers, increase inequity or competition for scarce resources, with multiplying effects. We need humanists to help us understand and respond to the social and ethical dimensions of technological change. As more changes come, we will need humanists to help us filter them, calibrate them, and when necessary, correct them. And we need them to galvanize the changes that are yet to come. Our focus should not be only on training students about the skills needed immediately upon graduation. The value of those skills will depreciate quickly. Instead, our aim is to invest in the long-term intellectual, creative, and social capacity of human beings.

I started by saying that we should embrace the debate about the value of the humanities. Let’s hear the criticisms that are often leveled, and do what we can to address them. Let’s make sure we give value to our students, and that we educate them for a variety of possible outcomes. Let’s do more to encourage cross-pollination between the sciences and the humanities for the benefit of each. Let’s educate all of our students in every discipline to use the best humanistic tools we have acquired over a millennium of university teaching—to engage in a civilized discourse about all of the great issues of our time. A grounding in the humanities will sharpen our answers to the toughest questions we are facing.

We don’t want a nation of technical experts in one subject. We want a scintillating civil society in which everyone can talk to everyone. That was a quality that Alexis de Tocqueville wrote of when he visited the United States at the beginning of the 1830s. Even in that era before mass communication, before the telegraph, before the internet, we were engaged in an American conversation that stretched from one end of the country to another. In a similar manner, Martin Luther King Jr. sketched a “web of mutuality” in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” fifty years ago this year. We want politicians who have read Shakespeare—as Lincoln did. We want bankers and lawyers who have read Homer and Dante. We want factory owners who have read Dickens.

It is really important we get this right. A mountain of empirical evidence indicates a growing inequality in our society. There is no better way to check this trend than to invest in education. And there is no better way to invest in education than to invest fairly, giving attention to all disciplines and short shrift to none.

Earlier generations have weighed these questions, and answered in the affirmative. An early graduate of Brown, Horace Mann, trained in the humanities, was instrumental in creating the public school system of the United States. He knew that a broad, secular education, open to all, was one of the foundations of our democracy, and that it was impossible to expect meaningful citizenship without offering people the tools to inform themselves about all of the great questions of life. Horace Mann said, “Be ashamed to die until you have won some victory for humanity.” In that spirit, let’s continue this conversation, eager to engage the critics in a spirited conversation whose very richness depends on the humanistic values we cherish.

And in conclusion: yes, it’s worth it.

![]() READING ARGUMENTS

READING ARGUMENTS

1. Paxson begins by acknowledging the difficulty of making “the case for the humanities” (para. 1). Why? Does this opening strategy undercut her argument in any way? Explain.

2. Does Paxson make a valid point in paragraph 2, or is she begging the question? Explain.

3. Where in the essay does Paxson appeal to ethos? Is this appeal effective in the context of her argument? Why or why not?

4. Paxson writes that “the humanities are in danger of becoming even more of a punching bag than they already are” (5). What evidence does she present to support this claim? Is this sufficient?

5. Paxson offers three strategies to stem the tide of criticism against the humanities. What are they? How effective have they been in stemming the “recent tide of criticism” (8)?

6. What point does Paxson make in her conclusion? Would a different concluding strategy have been more effective? Explain.

MAJOR DIFFERENCES: WHY UNDERGRADUATE MAJORS MATER

ANTHONY P. CARNEVALE AND MICHELLE MELTON

This essay was published in the Fall 2011 issue of Presidency, a publication of the American Council on Education.

In the United States today, there is no more certain investment than a college education. In spite of the current gloomy economic forecast, college is still worth it. In fact, rising demand, coupled with the persistent undersupply of college-educated workers over the last 30 years, has driven up relative wages for these workers. On average, college graduates make 84 percent more over a lifetime than their high school—educated counterparts—up from 75 percent in 1999. While the current unemployment rate among recent college graduates is high (9 percent), it is still far lower than the average unemployment rate for recent high school graduates (35 percent). When it rains long enough and hard enough, everyone gets a little wet. Still, a college education is the best umbrella to shelter individuals from economic storms.

But that doesn’t mean that all bachelor’s degrees are created equal. While the focus recently has been on the value of higher education in general, we have failed to connect the dots between specific college majors and specific career trajectories. College offers many non-financial benefits, but there is new evidence of the oversize influence that certain majors have in preparing students for careers. Average salaries mask very real discrepancies between the economic advantages of different undergraduate majors. While everyone who attends college can expect a significant return on their investment, different undergraduate majors lead to markedly different careers—and significantly different earnings.

Disparity in Degrees

As we found in our recent study, What’s It Worth?: The Economic Value of College Majors, because of the role it plays in occupational training, the choice of undergraduate major is as critical a choice as whether to get a college degree at all. In one of the most extreme examples, for instance, Counseling Psychology majors make an average of $29,000 per year, compared to $120,000 for Petroleum Engineering majors. That’s a difference of 314 percent—or $4.1 million over a 45-year lifetime of work. A more typical example is the difference between two of the most popular majors, General Business and Elementary Education. A General Business major earns $60,000 annually, compared with $40,000 for an Education major. Over a lifetime, that’s a difference in earnings of about $900,000.

Majors are so decisive for an individual’s earnings because they are not just educational categories; majors are an essential component of career training. Critics constantly disparage higher education for not being more connected with the “real world,” and for failing to more tightly align higher education and curricula with labor markets. Such criticism is off the mark; since the end of the Second World War, the growth in higher education has been in programs that connect learning with careers. Very few people today actually major in Ancient Greek, and you won’t see any subway advertisements promoting class offerings in Classics. Fewer than 10 percent of bachelor’s degrees in the U.S. economy are in Humanities and Liberal Arts. The growth areas of higher education have been, and will continue to be, in educational programs which stress career training. The for-profit sector has recognized this fact, and has profited handsomely from it. All of higher education would benefit from making the implicit relationships between education and careers more explicit.

“We have glossed over the differences between workers with a major in Mathematics and workers with a major in Drama and Theater Arts to the detriment of students.”

The point is a simple one: while it is important to discuss the benefits of college in general, for too long we have treated all college degrees as though they had the same economic value. We have glossed over the differences between workers with a major in Mathematics and workers with a major in Drama and Theater Arts to the detriment of students. The plain truth is that the labor market does not treat these workers the same—and students deserve to know that. A love of Shakespeare should not deter students from becoming English majors. But we believe that students should know how their educational choices will affect the rest of their adult lives, in terms of the careers they will have, their expected earnings, and whether they are likely to need graduate education—which they may need to take out loans to get.

We found that, for example, a Nursing major nearly always leads to a career in the Health Services industry, as do many other health preparatory majors (82 percent of Nursing majors end up in Health Professional occupations, and 6 percent are in management). Likewise, well over two-thirds of Education majors—especially Special Needs Education, Elementary Education, and Educational Administration and Supervision majors—end up in the Education Services industry.

Making the Arts Pay

That these particular majors lead to specific careers may be obvious—but what about Arts majors? Do most people who major in Arts actually become artists? In fact, only a quarter of Arts majors end up in Arts occupations, while about a third end up in either Office, Sales, or Education occupations. In other words, majoring in Arts only rarely leads to a career as an artist. Potential Arts majors should know this, and that they can expect median annual earnings of $44,000.

Of course, some Arts majors will end up going on to get a graduate degree (in fact, less than a quarter of Arts majors, 23 percent, do get a graduate degree). But Arts majors who get a graduate degree see a 23 percent boost in earnings.

Although it is slightly more remunerative than Arts, Humanities and Liberal Arts majors are in the middle of the pack in terms of earnings ($47,000) and graduate degree attainment (41 percent of Humanities and Liberal Arts majors go to graduate school). Humanities and Liberal Arts majors that do go on to graduate school see a 48 percent earnings boost for doing so, making their median earnings $65,000 per year. This is a comfortable living, to be sure, but even with a graduate degree, Humanities and Liberal Arts majors still make significantly less than an Engineering major with a bachelor’s degree. Moreover, in terms of all graduate earnings, Humanities and Liberal Arts majors are still in the middle of the pack. They earn more than the Arts majors do, but significantly less than many other major groups with a graduate degree, including Engineering, Health, Social Sciences, and Agriculture and Natural Resources.

In short, the Humanities and Liberal Arts may have unlimited intrinsic value, but in terms of their more measurable market value, these graduates simply do not fare as well as students whose majors equip them with more technical and scientific skills.

The point is not for students to slavishly choose the majors with the highest earnings, instead of being driven by their interests. It is to provide the information to students so that they are not solely driven by incomplete, anecdotal, or speculative evidence about their likely success, and to balance their interests—both economic and humanistic—in making a decision about their working lives.

Given information, students might make different decisions. We already know that such decisions are complex and based on a combination of interests, values, knowledge, skills, and abilities. If a Social Work major is motivated by the desire to interact with and help others, he or she might decide that, compared with $39,000 in Social Work, Nursing (at $60,000) might be a better option that would also allow him or her to pursue interacting with and helping others. The same might be true of a Biology major ($50,000), to whom Nursing might be an appealing alternative path. Similarly, an English major ($48,000) might decide that the small boost from majoring in Journalism ($51,000) isn’t worth the switch.

We have been embarrassingly slow to provide students with information that will help them make these decisions. For the most part, this is because higher education is balancing competing—and often contradictory—missions. Many educators are wary about subjugating higher education’s traditional role to an economic one. Some are upset about the increasingly tight ties that bind work and education. While training foot soldiers for capitalism is not the sole mission of our education system, the inescapable reality is that ours is a society based on work. Those who are not equipped with the knowledge and skills necessary to get—and keep—good jobs are denied full social inclusion and tend to drop out of the mainstream culture, polity, and economy. In the worst cases, they can be drawn into alternative cultures, political movements, and economic activities that are a threat to mainstream American life. Therefore, if postsecondary educators cannot fulfill their economic mission to help students become successful workers and to better link postsecondary education with careers, they also will fail in their cultural and political missions to create good neighbors and good citizens.

![]() READING ARGUMENTS

READING ARGUMENTS

1. In paragraph 3, Carnevale and Melton say that “the choice of undergraduate major is as critical a choice as whether to get a college degree at all.” What evidence do they provide to support this statement? Is this evidence convincing?

2. Carnevale and Melton write, “Critics constantly disparage higher education for not being more connected with the ’real world,’ and for failing to more tightly align higher education and curricula with labor markets” (para. 4). Why do they believe that this criticism is “off the mark” (4)?

3. According to Carnevale and Melton, their purpose is to provide information about the “economic and humanistic” (11) trade-offs of different majors. Do you agree with the writers that many—or most—college students make decisions about their major based on “incomplete, anecdotal, or speculative evidence” (11)? Why or why not?

4. In what respects is this essay an evaluation argument? In what sense is it a proposal argument?

5. Where in this essay do the authors develop a causal chain? What point are they trying to make with this strategy? Are they successful? Explain.

IS IT TIME TO KILL THE LIBERAL ARTS DEGREE?

KIM BROOKS

This piece initially appeared in Salon on June 19, 2011.

Every year or two, my husband, an academic advisor at a prestigious Midwestern university, gets a call from a student’s parent. Mr. or Mrs. So-and-so’s son is a sophomore now and still insistent on majoring in film studies, anthropology, Southeast Asian comparative literature or, god forbid . . . English. These dalliances in the humanities were fine and good when little Johnny was a freshman, but isn’t it time now that he wake up and start thinking seriously about what, one or two or three years down the line, he’s actually going to do?

My husband, loyal first and foremost to his students’ intellectual development, and also an unwavering believer in the inherent value of a liberal arts education, tells me about these conversations with an air of indignation. He wonders, “Aren’t these parents aware of what they signed their kid up for when they decided to let him come get a liberal arts degree instead of going to welding school?” Also, he says, “The most aimless students are often the last ones you want to force into a career path. I do sort of hate to enable this prolonged adolescence, but I also don’t want to aid and abet the miseries of years lost to a misguided professional choice.”

Now, I love my husband. Lately, however, I find myself wincing when he recounts these stories.

“Well,” I sometimes say, “what are they going to do?”

The answer, at least according to a recent article in the New York Times, is rather bleak. Employment rates for college graduates have declined steeply in the last two years, and perhaps even more disheartening, those who find jobs are more likely to be steaming lattes or walking dogs than doing anything even peripherally related to their college curriculum. While the scale and severity of this post-graduation letdown may be an unavoidable consequence of an awful recession, I do wonder if all those lofty institutions of higher learning, with their noble-sounding mission statements and soft-focused brochure photos of campus greens, may be glossing over the serious, at-times-crippling obstacles a B.A. holder must overcome to achieve professional and financial stability. I’m not asking if a college education has inherent value, if it makes students more thoughtful, more informed, more enlightened and critical-minded human beings. These are all interesting questions that don’t pay the rent. What I’m asking is far more banal and far more pressing. What I’m asking is: Why do even the best colleges fail so often at preparing kids for the world?

When I earned my diploma from the University of Virginia in the spring of 2000, it never occurred to me before my senior year to worry too seriously about my post-graduation prospects. Indeed, most of my professors, advisors, and mentors reinforced this complacency. I was smart, they told me. I’d spent four years at a rigorous institution honing my writing, research, and critical-thinking skills. I’d written an impressive senior thesis, gathered recommendations from professors, completed summer internships in various journalistic endeavors. They had no doubt at all that I would land on my feet. And I did (kind of), about a decade after graduating.

In the interim, I floundered. I worked as a restaurant hostess and tutored English-as-a-second-language without a formal work visa. I mooched off friends and boyfriends and slept on couches. One dreary night in San Francisco, I went on an interview to tend bar at a strip club, but left demoralized when I realized I’d have to walk around in stilettos. I went back to school to complete the pre-medical requirements I’d shunned the first time through, then, a week into physics, I applied to nursing school, then withdrew from that program after a month when I realized nursing would be an environment where my habit of spacing out might actually kill someone. I landed a $12-an-hour job as a paralegal at an asbestos-related litigation firm. I got an MFA in fiction.

Depending on how you look at it, I either spent a long time finding myself, or wasted seven years. And while all these efforts hardly add up to a tragedy (largely because I had the luxury of supportive parents willing to supplement my income for a time), I do have to admit feeling disillusioned as I moved from one gig to another, feeling as though my undergraduate education, far from preparing me for any kind of meaningful and remunerative work, had in some ways deprepared me, nurturing my natural strengths and predilections—writing, reading, analysis—and sweeping my weaknesses in organization, pragmatic problem-solving, decision-making under the proverbial rug.

Of course, there are certainly plenty of B.A. holders out there who, wielding the magic combination of competency, credentials, and luck, are able to land themselves a respectable, entry-level job that requires neither name tag nor apron. But for every person I know who parlayed a degree in English or anthropology into a career-track gig, I know two others who weren’t so lucky, who, in that awful, post-college year or two or three or four, unemployed and uninsured and uncommitted to any particular field, racked up credit card debt or got married to the wrong person or went to law school for no particular reason or made one of a dozen other time- and money-wasting mistakes.

“And the common thread in all these stories seems to be how surprised these graduates were by their utter unemployability.”

And the common thread in all these stories seems to be how surprised these graduates were by their utter unemployability, a feeling of having been misled into complacency, issued reassurances about how the pedigree or prestige of the institution they’d attended would save them. This narrative holds true whether their course of study was humanities or social sciences. My baby sitter, for example, who earned a degree in psychology from a Big Ten university, now makes $15 an hour watching my kids.

“I was not the most serious student,” she admits. “But I do wonder, why was I allowed to decide on a major without ever sitting down with my advisor and talking about what I might do with that major after graduating? I mean, I had to write out a plan for how I’d fit all my required courses into my schedule, but no one seemed to care if I had a plan once I left there. I graduated not knowing how to use Excel, write out a business plan, do basic accounting. With room and board and tuition, my time there cost $120,000.”

I asked Sarah Isham, the director of career services of the College of Arts and Sciences at my alma mater about this discrepancy between curriculum and career planning, and she repeats the same reassurances I heard 10 years ago: “What we do is help students see how the patterns and themes of their interests, skills, and values, might relate to particular arenas. We do offer a few self-assessment tests, as well as many other resources to help them do this.”

When I ask how well the current services are working—that is, how many recent graduates are finding jobs, real jobs that require a degree—she can only say that, “The College of Arts and Sciences does not collect statistics on post-graduation plans. I could not give you any idea of where these students are going or what they are doing. Regrettably, it’s not something in place at this time.”

I went on to ask her how the college’s curriculum was adapting to meet the demands of the recession and the realities of the job market, and she directed me to a dean who asked not to be identified, and who expressed, in no uncertain terms, how tired he was of articles like mine that question the rationale, rigor, or usefulness of a liberal arts education. He insisted that while he had no suggestions regarding how a 22-year-old should weather a recession, the university was achieving its goal of creating citizens of the world.

When I asked him how a 22-year-old with no job, no income, no health insurance, and, in some cases, six figures of college debt to pay off is supposed to be a citizen of the world, he said he had no comment, that he was the wrong person to talk to, and he directed me to another dean, who was also unable to comment.

The chilliness of this response was a bit disheartening, but not terribly surprising. When I was an undergrad, it seemed whenever I mentioned my job-search anxieties, my professors and advisors would get a glassy look in their eyes and mutter something about the career center. Their gazes would drift toward their bookshelves or a folder of ungraded papers. And at the time, I could hardly blame them. These were people who’d published dissertations on Freud, written definitive volumes on Virginia Woolf. The language of real-world career preparation was a language they simply didn’t speak.

And if they did say anything at all, it was usually a reiteration of the typical liberal arts defense, that graduating with a humanities degree, I could do anything: I could go on to earn a master’s or a law degree or become an editor or a teacher. I could go into journalism or nonprofit work, apply to medical school or the foreign service. I could write books or learn to illustrate or bind them. I could start my own business, work as a consultant, get a job editing pamphlets for an alumni association, or raise money for public radio. The possibilities were literally limitless. It was a like being 6 years old again and trying to decide if I’d become an astronaut or a ballerina. The advantage to a humanities degree, one professor insisted, was its versatility. In retrospect, though, I wonder if perhaps this was part of the problem, as well; freedom can promote growth, but it can also cause paralysis. Faced with limitless possibilities, a certain number of people will just stand still.

“So let me ask you something,” my husband says, my wonderfully incisive husband who will let me get away with only so much bitterness. “If your school had forced you to declare a career plan or take an accounting class or study web programming instead of contemporary lit, how would you have felt about it at the time, without the benefit of hindsight?”

It’s a good question, and the answer is, I probably would have transferred.

There were courses I took in college, courses in Renaissance literature and the anthropology of social progress and international relations of the Middle East and, of course, writing, that will, in all likelihood, never earn me a steady paycheck or a 401K, but which I would not trade for anything; there were lectures on Shakespeare and Twain and Joyce that I still remember, that I’ve dreamt about and that define my sensibility as a writer and a reader and a human being. Even now, knowing the lost years that followed, I still wouldn’t trade them in.

A new Harvard study suggests that it’s not an abandonment of the college curriculum that’s needed, but a reenvisioning and better preparation. The study compares the U.S. system unfavorably to its European counterparts where students begin thinking about what sort of career they’ll pursue and the sort of preparation they’ll need for it in middle school. Could that be the answer?

At the end of my interview with Sarah Isham, she asks me if I might come back to Charlottesville to participate in an alumni career panel. “We always have a lot of students interested in media and writing and the arts. It would be wonderful,” she says “to have you come and talk to them.” She asks me this, and I can’t help but laugh.

“I don’t think I’d be much of a role model,” I say. “I don’t have what you’d call a high-powered career. I mostly do freelance work. Adjunct teaching. That sort of thing.”

“Oh, that’s fine,” she insists. “Our students will love that. So many of them are terrified of sitting in a cubicle all day.”

They should be so lucky, I think. But I would never say that—not to them and not to my own students. They’ll have plenty of time later to find out just what a degree is and isn’t good for. Right now, they’re in those four extraordinary, exceptional years where ideas matter; and there’s not a thing I’d do to change that.

![]() READING ARGUMENTS

READING ARGUMENTS

1. At two points in her essay, Brooks discusses her husband. Do you think these discussions help her advance her argument? If so, how?

2. Brooks’s thesis occurs at the end of paragraph 5. Is this a logical place for it, or should it come earlier?

3. What evidence does Brooks use to support her points? Is this support convincing? What other kinds of evidence could she have used? What are the advantages and disadvantages of using such evidence?

4. What does Brooks mean when she says that the liberal arts graduates she interviewed have “a feeling of having been misled into complacency” (para. 10)?

5. How would you describe the tone of Brooks’s essay? How does this tone affect your response to her argument?

6. What does Brooks think the purpose of college should be? Do you agree with her? Why or why not?

COURSE CORRECTIONS

THOMAS FRANK

Harper’s published this essay in its October 2013 issue.

To the long list of American institutions that have withered since the dawn of the 1980s—journalism, organized labor, mainline Protestantism, small-town merchants—it may be time to add another: college-level humanities. Those ancient pillars of civilization are under assault these days, with bulldozers advancing from two different directions.

On the one hand, students are migrating away from traditional college subjects like history and philosophy. After hitting a postwar high in the mid-1960s, enrollments in the humanities dropped off sharply, and still show no signs of recovering. This is supposedly happening because recent college grads who chose to major in old-school subjects have experienced more difficulty finding jobs. Indeed, the folly of studying, say, English Lit has become something of an internet cliché—the stuff of sneering “Worst Majors” listicles that seem always to be sponsored by personal-finance websites.

On the other hand, an impressive array of public figures are eager to give the exodus from the humanities an additional push. Everyone from President Obama to Thomas Friedman knows where public support for education has to be concentrated in order to yield tangible returns both for individuals and for the nation: the STEM disciplines (science, technology, engineering, and math). These are the degrees American business is screaming for. These are the fields of study that will give us “broadly shared economic prosperity, international competitiveness, a strong national defense, a clean energy future, and longer, healthier, lives for all Americans,” as a White House press release puts it.

“Where does that leave the humanities, which don’t contribute in any obvious way to national defense or economic prosperity?”

Where does that leave the humanities, which don’t contribute in any obvious way to national defense or economic prosperity? The management theorist and financier Peter Cohan, addressing unemployment among recent college grads in the pages of Forbes, proposes a course of straightforward erasure: “To fix this problem, the answer is simple enough: cut out the departments offering majors that make students unemployable.” Certain red-state governors seem eager to take up the task. Governor Pat McCrory of North Carolina, for example, dismisses gender studies as elitist woolgathering and announces, “I’m going to adjust my education curriculum to what business and commerce needs.” Governor Rick Scott of Florida declares that “we don’t need a lot more anthropologists in the state,” while a panel he convened in 2012 has called for tuition prices to be subsidized for those willing to acquiesce to the needs of business and study practical things. Those who want to study silly stuff like divinity or Latin will have to pay ever more to indulge in their profligate pastimes.

And so the old battle is joined again: the liberal arts versus professional (i.e., remunerative) studies. This time around, of course, it is flavored by all the cynical stratagems of contemporary politics. Take the baseline matter of STEM workers, the ones who supposedly hold our future in their hands. According to a recent study by the Economic Policy Institute, there is actually no shortage of STEM workers in the United States—and by extension, no need for all the incentives currently on the table to push more students into those fields. Oh, the demand of the business community for an ever greater supply of STEM grads is genuine enough. But their motive is the same as it was when they lobbied for looser restrictions on STEM workers from abroad: to keep wages down. Only this time the high-handed endeavor is being presented as a favor to students, who must be rescued from a lifetime of philology-induced uselessness.

A similar logic explains the larger attack on the humanities. The disciplines in the crosshairs have been the right’s nemeses for many years. Maybe, in the past, conservatives stumped for some idealized core curriculum or the Great Books of Western Civ—but now that the option of demolishing these disciplines is on the table, today’s amped-up right rather likes the idea. After all, universities are not only dens of liberal iniquity but also major donors to the Democratic Party.1 Chucking a few sticks of dynamite into their comfy world is a no-brainer for any politician determined to “defund the left.”

Fans of the banality of evil might appreciate the language with which this colossal act of vandalism is being urged upon us. Florida’s blue-ribbon commission, for example, sets about burying the humanities with a sandstorm of convoluted management talk:

Four key policy questions must be addressed to accelerate Florida’s progression toward world-class recognition as a system, particularly as its measurement framework transitions from simply reporting to collaborating toward clear goals. . . . Boards can advance effective cost management by helping to shape the conversation about aligning resources with goals and creating a culture of heightened sensitivity to resource management across the campus.

Let us assess the battle so far. In one corner, we have rhetoric like this: empty, pseudoscientific jargon rubber-stamped by a Chamber of Commerce hack . . . who was appointed by the governor of Florida . . . who was himself elected by the Tea Party. It is not merely weak, it is preposterous; it is fatuity at a gallop.

In the other corner, we have the university-level humanities. Now, here is an antagonist at the height of its vast mental powers. In polite and affluent circles, it is respected by all. Its distinctive, plummy tone seems daily to extend itself into more and more aspects of American life. The Opinion section of the Sunday New York Times, for example, is one long succession of professorial musings. So is much of NPR’s programming. Former humanities students occupy many of the seats in President Obama’s Cabinet.

That the exalted men and women of higher learning might take the field against opponents like the authors of the Florida report and be defeated—it’s almost impossible to believe. And yet that’s precisely what is happening.

Stung by the attacks on their livelihood, the nation’s leading humanists have closed ranks, taken up their pencils, and tried to explain why they exist. The result is a train wreck of desperate rationalizations, clichés, and circular reasoning.

They insist that their work must not be judged by bogus metrics like the employability of recent graduates. They scold journalists for getting the story wrong in certain of its details. They express contempt for the dunces in state legislatures. They tear into the elected philistines who badger them with what the academic superstar Homi Bhabha calls a “primitive and reductive view of what is essential.”

And with touching earnestness, they argue that the humanities are plenty remunerative. They tell of CEOs who demand well-rounded young employees rather than single-minded, vocationally focused drudges. They remind us that humanities grads get into law and medical schools, which in turn lead (as everyone knows, right?) to the big money. Besides, they point out, the humanist promise of explaining our mysterious country draws foreign students—and foreign currency—to college towns across the land. They even play the trump card of national security: wouldn’t we have done better in the global “war on terror” if we had trained more Arabic linguists prior to the start of hostilities?

Their mission, after all, is not about money: it is about molding young citizens for democracy! In making this traditional argument, no one today will venture quite as far as Bruce Cole, a former chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, who in 2004 claimed that the humanities were “part of our homeland defense.” But we’re getting pretty close. Consider the report issued a few months ago by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, which asserts that our political system itself “depends on citizens who can think critically, understand their own history, and give voice to their beliefs while respecting the views of others.” As proof, the authors of the report cite Thomas Jefferson’s fondness for liberal education, and then proceed to trumpet the humanities as nothing less than “the keeper of the republic”—a phrase that is doubtless meant to out-patriot the various conservatives nipping at the academy’s ankles.2

Others want nothing to do with such hackneyed arguments. Harvard University’s effort to explain the high station of the humanities, a dense and confusing text issued in June, insists that these disciplines are designed in part to “unmask the operations of power,” not to buttress them. The document then disavows Harvard’s previous justification for the humanities, which had stressed the “civic responsibilities of American citizens living in and aspiring to preserve a free democratic society.” No, that was last century’s model—jingoistic junk. In 2013, the humanities are all about embracing ambiguity. And about determining exactly what the humanities are about. The humanists write:

At the same time, therefore, that we aspire to ground our sense of ourselves on some stable understanding of the aim of life (e.g., the responsible citizen in a free society), we must constantly aspire to discover anew what the best way to characterize and cultivate such an aim might be. The humanities are the site where this tension is cultivated, nurtured, and sustained.3

The nurturing and sustaining of tensions—that’s the stuff. Of course, some tensions are more desirable than others, and for all their excitement about the unmasking of power, the Harvard humanists have little interest in unmasking their own. Nor should their genuflection at the altar of ambiguity be taken as a call to knock down the disciplinary walls. No, according to Bhabha’s navel-gazing appendix, even students interested in interdisciplinary studies will be D.O.A. unless they first encounter “disciplinary specificity in its most robust expression.” Ambiguity is a stern taskmaster, I guess.

Most touching, perhaps, is the argument advanced by Stanley Fish in a 2010 New York Times Opinionator column. After shooting down the many absurd defenses of the humanities that are floating around these days, Fish advises inhabitants of academia’s more rarefied regions to forget even trying to explain themselves to the public. Don’t ask what “French theory” does for the man in the street, Fish writes. Instead, ask whether its

insights and style of analysis can be applied to the history of science, to the puzzles of theoretical physics, to psychology’s analysis of the human subject. In short, justify yourselves to your colleagues, not to the hundreds of millions of Americans who know nothing of what you do and couldn’t care less and shouldn’t be expected to care.

Once, academics like Fish dreamed of bringing young people to a full understanding of their humanity, and maybe even of changing the world. Now their chant is: We’re experts because other experts say we’re experts. We critique because we critique because we critique—but all critique stops at the door to the faculty lounge.

One thing the humanities warriors don’t talk about very much is the cost of it all. In the first chapter of Martha Nussbaum’s otherwise excellent Not for Profit, the author declares that while the question of “access” to higher ed is an important one, “it is not, however, the topic of this book.”

Maybe it should have been. To discuss the many benefits of studying the humanities absent the economic context in which the humanities are studied is to miss the point entirely. When Americans express doubts about whether (in the words of Obama pollster Joel Benenson) “a college education was worth it,” they aren’t making a judgment about the study of history or literature that needs to be refuted. They are remarking on its price.

Tellingly, not a single one of the defenses of the humanities that I read claimed that such a course of study was a good deal for the money. The Harvard report, amid its comforting riffs about ambiguity, suggests that bemoaning the price is a “philistine objection” not really worth addressing. (It also dismisses questions of social class with a footnote.) The document produced by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences contains numerous action points for sympathetic legislators, but devotes just two paragraphs to the subject of student debt and tuition inflation, declaring blandly that “colleges must do their part to control costs,” then suggesting that the real way to deal with the problem is to do a better job selling the humanities.

But ignoring basic economics doesn’t make them go away. It is supposed to be a disaster when right-wingers in state legislatures threaten to destroy academic professions. However, one reason the world has so little sympathy for those professions is that everyone knows how they themselves cranked out Ph.D.’s for decades without considering whether there was a demand for said Ph.D.’s, thereby transforming their own dedicated disciples into the most piteous wretches on campus.

Still, the wretchedness they ought to be considering is of a different magnitude altogether. The central economic fact of American higher ed today is this: It costs a lot. It costs a huge amount. It costs so much, in fact—more than $60,000 a year for tuition plus expenses at a growing number of top private schools—that young people routinely start their postcollegiate lives with enormous debt loads. It’s like forcing them to take out a mortgage when they turn twenty-two, only with no white picket fence to show for it.

This is the woolly mammoth in the room. I know the story of how it got there is a complicated one. But regardless of how it happened, that staggering price tag has changed the way we make educational decisions. Quite naturally, parents and students alike have come to expect some kind of direct, career-prep transaction. They’re out $240,000, for Christ’s sake—you can’t tell them it was all about embracing ambiguity. For that kind of investment, the gates to a middle-class life had better swing wide!

No quantity of philistine-damning potshots or remarks from liberal-minded CEOs will banish this problem. Humanists couldn’t stop the onslaught even if they went positively retro and claimed they were needed to ponder the mind of God and save people’s souls. The turn to STEM is motivated by something else, something even more desperate and more essential than that.

What is required is not better salesmanship or reassuring platitudes. The world doesn’t need another self-hypnotizing report on why universities exist. What it needs is for universities to stop ruining the lives of their students. Don’t propagandize for your institutions, professors: Change them. Grab the levers of power and pull.

![]() READING ARGUMENTS

READING ARGUMENTS

1. Frank observes that the debate about the value of a liberal arts education is nothing new: “And so the old battle is joined again: the liberal arts versus professional (i.e., remunerative) studies. This time around, of course, it is flavored by all the cynical stratagems of contemporary politics” (para. 5). What evidence does Frank provide to support this statement? Does he seem to favor one political party over another? Explain.

2. Frank quotes specific language from both detractors of a liberal arts education (such as the Florida commission [7]) and its defenders (such as the “Harvard humanists” [15]). Why does he focus on their language? How does his analysis support his main argument?

3. Frank repeatedly uses the word philistine—for example, when he refers to the “elected philistines who badger” liberal arts professors (12). What is a “philistine”? Why is the word significant in the context of this debate?

4. According to Frank, what is the “central economic fact of American higher ed today” (21)?

5. In his conclusion, Frank advises universities to “grab the levers of power and pull” (24). What does he mean? What other point (or points) could he have emphasized here?

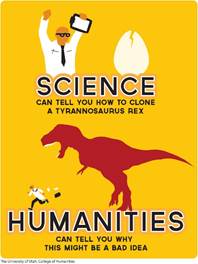

VISUAL ARGUMENT: MATH VS. HUMANITIES

This image was created by the College of the Humanities at the University of Utah to promote the value of humanities courses.

The poster reads, A squared plus B squared equals C squared. The next line reads, Math. A background image is a right angle triangle. The text below reads, Can help you understand the Pythagorean theorem. Another text below reads, Humanities can help you understand 2 B or not 2 B. The logo below reads, U College of Humanities The University of Utah. Illuminating your world. W w w dot hum dot Utah dot edu.

![]() READING ARGUMENTS

READING ARGUMENTS

1. How would you summarize the argument of the visual in your own words?

2. What contemporary argument or issue is this visual addressing? Does it seem to be a refutation—that is, an argument against a specific position—or a clever restatement of conventional wisdom? Explain.

3. The image relies on a pun, or play on words, to make its point. How does this stylistic element support the overall argument of the visual? For example, what contrast is being highlighted?

![]() AT ISSUE: DOES IT PAY TO STUDY THE HUMANITIES?

AT ISSUE: DOES IT PAY TO STUDY THE HUMANITIES?

1. Carnevale and Melton write in paragraph 13 about the difficulties colleges and universities have trying to balance conflicting missions:

Many educators are wary about subjugating higher education’s traditional role to an economic one. Some are upset about the increasingly tight ties that bind work and education. While training foot soldiers for capitalism is not the sole mission of our education system, the inescapable reality is that ours is a society based on work.

o Do you agree that there is a tension between these two “missions”? How should educators maintain a balance between their intellectual mission and the more practical demands of preparing graduates for work?

2. In her essay, Brooks asks, “Why do even the best colleges fail so often at preparing kids for the world?” (para. 5). How would you answer this question? When it comes to your college, do you agree or disagree with Brooks’s contention?

3. According to Paxson, “We don’t want a nation of technical experts in one subject. We want a scintillating civil society in which everyone can talk to everyone” (17). What does she mean? For example, what is a “civil society”? How are the values conveyed by the liberal arts related to civil society and public discourse? What problems might arise from having a nation composed almost entirely of highly specialized “technical experts in one subject”?

![]() WRITING ARGUMENTS: DOES IT PAY TO STUDY THE HUMANITIES?

WRITING ARGUMENTS: DOES IT PAY TO STUDY THE HUMANITIES?

1. After reading the arguments in this casebook, develop your own ideas about whether it pays to study the humanities. Then, using these essays as sources, write an essay in which you argue for your position.

2. As Frank points out, educators, policymakers, politicians, and others have been strongly encouraging young Americans to major in a STEM discipline. Are you planning on studying one of these disciplines? If not, have you felt pressure from parents, teachers, or friends to pursue science, technology, engineering, or math? Write an essay that answers these questions and takes a position on the issue.