Practical argument: A text and anthology - Laurie G. Kirszner, Stephen R. Mandell 2019

The four pillars of argument

Understanding argument

AT ISSUE

Is a College Education Worth the Money?

In recent years, more and more high school graduates have been heading to college, convinced that higher education will enhance their future earning power. At the same time, the cost of a college education has been rising, and so has the amount of student-loan debt carried by college graduates. (During 2017—18, average tuition and fees at nonprofit private four-year colleges rose 1.9 percent, to $34,740, while tuition for in-state students at four-year public schools went up 1.3 percent to $9,970. On average, 2017 graduates with student-loan debt owed nearly $40,000.) This situation has led some observers to wonder if the high cost of college actually pays off—not only in dollars but also in future job satisfaction. Will a college degree protect workers who are threatened by high unemployment, the rise of technology, the declining power of labor unions, and the trend toward outsourcing? Given the high financial cost of college, do the rewards of a college education—emotional and intellectual as well as financial—balance the sacrifices that students make in time and money? These and other questions have no easy answers.

Later in this chapter, you will be introduced to readings that explore the pros and cons of investing in a college education, and you will be asked to write an argumentative essay in which you take a position on this controversial topic.

In a sense, you already know a lot more than you think you do about how to construct an argumentative essay. After all, an argumentative essay is a variation of the thesis-and-support essays that you have been writing in your college classes: you state a position on a topic, and then you support that position. However, with argumentative essays, some special concerns in terms of structure, style, and purpose come into play. Throughout this book, we introduce you to the unique features of argument. In this chapter, we focus on structure.

The Elements of Argument

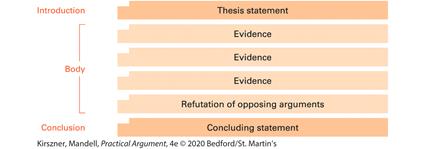

An argumentative essay includes the same three sections—introduction, body, and conclusion—as any other essay. In an argumentative essay, however, the introduction includes an argumentative thesis statement, the body includes both the supporting evidence and the refutation of opposing arguments, and the conclusion includes a strong, convincing concluding statement that reinforces the position stated in the thesis.

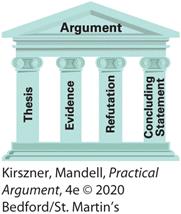

The following diagram illustrates one way to organize an argumentative essay.

The Introduction comprises the Thesis statement. The Body includes Evidence, Evidence, Evidence, and Refutation of opposing arguments. The Conclusion includes the Concluding statement.

The elements of an argumentative essay are like the pillars of an ancient Greek temple. Together, the four elements—thesis statement, evidence, refutation of opposing arguments, and concluding statement—help you build a strong argument.

Thesis Statement

The roof of the building reads, Argument, and the first pillar reads, Thesis.

A thesis statement is a single sentence that states your position on an issue. An argumentative essay must have an argumentative thesis—one that takes a firm stand. For example, on the issue of whether colleges should require all students to study a language other than English, your thesis statement could be any of the following (and other positions are also possible):

§ Colleges should require all students to study a foreign language.

§ Colleges should require all liberal arts majors to study a foreign language.

§ Colleges should require all students to study Spanish, Chinese, or Farsi.

§ Colleges should not require any students to study a foreign language.

An argumentative thesis must be debatable—that is, it must have at least two sides, stating a position with which some reasonable people might disagree. To confirm that your thesis is debatable, you should see if you can formulate an antithesis, or opposing argument. For example, the statement, “Our school has a foreign-language requirement” has no antithesis because it is simply a statement of fact; you could not take the opposite position because the facts would not support it. However, the following thesis statement takes a position that is debatable (and therefore suitable for an argumentative thesis):

THESIS

Our school should institute a foreign-language requirement.

ANTITHESIS

Our school should not institute a foreign-language requirement.

(For more on thesis statements, see Chapter 7.)

Evidence

The roof of the building reads, Argument. The first pillar reads, Thesis. The second pillar reads, Evidence.

Evidence is the material—facts, observations, expert opinion, examples, statistics, and so on—that supports your thesis statement. For example, you could support your position that foreign-language study should be required for all college students by arguing that this requirement will make them more employable, and you could cite employment statistics to support this point. Alternatively, you could use the opinion of an expert on the topic—for example, an experienced college language instructor—to support the opposite position, arguing that students without an interest in language study are wasting their time in such courses.

You will use both facts and opinions to support the points you make in your arguments. A fact is a statement that can be verified (proven to be true). An opinion is always open to debate because it is simply a personal judgment. Of course, the more knowledgeable the writer is, the more credible his or her opinion is. Thus, the opinion of a respected expert on language study will carry more weight than the opinion of a student with no particular expertise on the issue. However, if the student’s opinion is supported by facts, it will be much more convincing than an unsupported opinion.

FACTS

§ Some community colleges have no foreign-language requirements.

§ Some selective liberal arts colleges require all students to have two years or more of foreign-language study.

§ At some universities, undergraduates must take as many as fourteen foreign-language credits.

§ Some schools grant credit for high school language classes, allowing these courses to fulfill the college foreign-language requirement.

UNSUPPORTED OPINIONS

§ Foreign-language courses are not as important as math and science courses.

§ Foreign-language study should be a top priority on university campuses.

§ Engineering majors should not have to take a foreign-language course.

§ It is not fair to force all students to study a foreign language.

SUPPORTED OPINIONS

§ The university requires all students to take a full year of foreign-language study, but it is not doing enough to support those who need help. For example, it does not provide enough student tutors, and the language labs have no evening hours.

§ According to Ruth Fuentes, chair of the Spanish department, nursing and criminal justice majors who take at least two years of Spanish have an easier time finding employment after graduation than students in those majors who do not study Spanish.

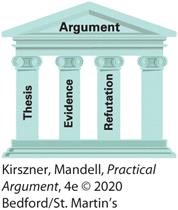

Refutation

The roof of the building reads, Argument. The first pillar reads, Thesis. The second pillar reads, Evidence. The third pillar reads, Refutation.

Because every argument has more than one side, you should not assume that your readers will agree with you. On the contrary, readers usually need to be convinced that your position on an issue has merit. This means that you need to do more than just provide sufficient evidence in support of your position; you also need to refute (disprove or call into question) arguments that challenge your position, possibly conceding the strengths of those opposing arguments and then pointing out their shortcomings.

For example, if you take a position in favor of requiring foreign-language study for all college students, some readers might argue that college students already have to take too many required courses. After acknowledging the validity of this argument, you could refute it by pointing out that a required foreign-language course would not necessarily be a burden for students because it could replace another, less important required course.

Other readers might point out that in today’s competitive job market, which is increasingly dependent on technology, it makes more sense to study coding than to study a foreign language. In this case, you would concede the strength of the position, acknowledging the importance of proficiency in computer languages. You could then go on to refute the argument by explaining that foreign-language study expands students’ ability to engage with people from other cultures, thereby becoming more competitive in a global economy. (You could also argue, of course, that students could benefit by studying both coding and foreign languages.) (For more on refutation, see Chapter 7.)

Concluding Statement

The roof of the building reads, Argument. The first pillar reads, Thesis. The second pillar reads, Evidence. The third pillar reads, Refutation, and the fourth pillar reads, Concluding Statement.

After you have provided convincing support for your position and refuted opposing arguments, you should end your essay with a strong concluding statement that reinforces your position. (The position that you want readers to remember is the one stated in your thesis, not the opposing arguments that you have refuted.) For example, you might conclude an essay in support of a foreign-language requirement by making a specific recommendation or by predicting the possible negative outcome of not implementing this requirement.

CHECKLIST

Does Your Argument Stand Up?

When you write an argumentative essay, check to make sure it includes all four of the elements you need to build a strong argument.

· Does your essay have an argumentative thesis?

· Does your essay include solid, convincing evidence to support your thesis?

· Does your essay include a refutation of the most compelling arguments against your position?

· Does your essay include a strong concluding statement?

WHY FOREIGN-LANGUAGE STUDY SHOULD BE REQUIRED

NIA TUCKSON

![]() The following student essay includes all four of the elements that are needed to build a convincing argument.

The following student essay includes all four of the elements that are needed to build a convincing argument.

The essay continues as follows:

First paragraph: “What do you call someone who speaks three languages? Trilingual. What do you call someone who speaks two languages? Bilingual. What do you call someone who speaks only one language? American.” [A corresponding margin note reads, Introduction] As this old joke illustrates, many Americans are unable to communicate in a language other than English. Given our global economy and American companies’ need to conduct business with other countries, this problem needs to be addressed. A good first step is to require all college students to study a foreign language. [A corresponding margin note reads, Thesis statement]

Second paragraph: [A margin note corresponding to the paragraph reads, First body paragraph: Evidence. End note.] Paragraph reads, After graduation, many students will work in fields in which speaking (or reading) another language will be useful or even necessary. For example, health-care professionals will often be called on to communicate with patients who do not speak English; in fact, a patient’s life may depend on their ability to do so. Those who work in business and finance may need to speak Mandarin or Japanese; those who have positions in the military or in the foreign service may need to speak Persian or Arabic. A working knowledge of one of these languages can help students succeed in their future careers, and it can also make them more employable.

Third paragraph: [A margin note corresponding to the paragraph reads, second body paragraph: Evidence. End note.] Paragraph reads, In addition to strengthening a résumé, foreign-language study can also give students an understanding of another culture’s history, art, and literature. Although such knowledge may never be “useful” in a student’s career, it can certainly enrich the student’s life. Too narrow a focus on career can turn college into a place that trains students rather than educates them. In contrast, expanding students’ horizons to include subjects beyond those needed for their careers can better equip them to be lifelong learners.

Third paragraph: [A margin note corresponding to the paragraph reads, third body paragraph: Evidence. End note.] Paragraph reads, When they travel abroad, Americans who can speak a language other than English will find that they are better able to understand people from other countries. As informal ambassadors for the United States, tourists have a responsibility to try to understand

The essay continues as follows:

The essay continues as follows: other languages and cultures. Too many Americans assume that their own country’s language and culture are superior to all others. This shortsighted attitude is not likely to strengthen relationships between the United States and other nations. Understanding a country’s language can help students to build bridges between themselves and others.

Fourth paragraph: [A margin note corresponding to the paragraph reads, Fourth body paragraph: Refutation of opposing argument. End note.] Paragraph reads, Some students say that learning a language is not easy and that it takes a great deal of time. College students are already overloaded with coursework, jobs, and family responsibilities, and a new academic requirement is certain to create problems. In fact, students may find that adding just six credits of language study will limit their opportunities to take advanced courses in their majors or to enroll in electives that interest them. However, this burden can be eased if other, less important course requirements — such as physical education — are eliminated to make room for the new requirement.

Fifth paragraph: [A margin note corresponding to the paragraph reads, Fourth body paragraph: Refutation of opposing argument. End note.] Some students may also argue that they, not their school, should be able to decide what courses are most important to them. After all, a student who struggled in high school French and plans to major in computer science might understandably resist a foreign-language requirement. However, challenging college language courses might actually be more rewarding than high school courses were, and the student who struggled in high school French might actually enjoy a college-level French course (or study a different language). Finally, a student who initially plans to major in computer science may actually wind up majoring in something completely different — or taking a job in a country in which English is not spoken.

Sixth paragraph: [A margin note corresponding to the paragraph reads, Conclusion. End note.] Entering college students sometimes find it hard to envision their personal or professional futures or to imagine where their lives may take them. Still, a well-rounded education, including foreign-language study, can prepare them for many of the challenges that they will face. Colleges can help students keep their options open by requiring at least a year (and preferably two years) of foreign-language study. Instead of focusing narrowly on what interests them today, American college students should take the extra step to become bilingual — or even trilingual — in the future [the sentence is annotated, Concluding statement. End note]

![]()

EXERCISE 1.1 IDENTIFYING THE ELEMENTS OF ARGUMENT

The following essay, “Learn a Language, but Not a Human One,” by Andy Kessler, includes all four of the basic elements of argument discussed so far. Read the essay, and then answer the questions that follow it, consulting the diagram on page 24 if necessary.

LEARN A LANGUAGE, BUT NOT A HUMAN ONE

ANDY KESSLER

This commentary appeared on July 17, 2017, in the Wall Street Journal.

Donald Trump, whose wife speaks five languages, just wrapped up a pair of trips to Europe during which he spoke only English. Good for him. If Mr. Trump studied a language in college or high school, as most of us were required to, it was a complete waste of his time. I took five years of French and can’t even talk to a French poodle.

Maybe there’s a better way for students to spend their time. Last month Apple CEO Tim Cook urged the president: “Coding should be a requirement in every public school.” I propose we do a swap.

Why do American schools still require foreign languages? Translating at the United Nations is not a growth industry. In the 1960s and ’70s everyone suggested studying German, as most scientific papers were in that language. Or at least that’s what they told me. In the ’80s it was Japanese, since they ruled manufacturing and would soon rule computers. In the ’90s a fountain of wealth was supposed to spout from post-Communist Moscow, so we all needed to learn Russian. Now parents elbow each other getting their children into immersive Mandarin programs starting in kindergarten.

Don’t they know that the Tower of Babel has been torn down? On your average smartphone, apps like Google Translate can do real-time voice translation. No one ever has to say worthless phrases like la plume de ma tante anymore. The app Waygo lets you point your phone at signs in Chinese, Japanese, or Korean and get translations in English. Sometime in the next few years you’ll be able to buy a Bluetooth-based universal translator for your ear.

Yet students still need to take at least two years of foreign-language classes in high school to attend most four-year colleges. Three if they want to impress the admissions officer. Four if they’re masochists. Then they need to show language competency to graduate most liberal-arts programs. We tried to get my son out of a college language requirement. He pointed to his computer skills and argued that the internet is in English. (It’s true. As of March, 51.6 percent of websites were in English. Just 2 percent were Chinese.) We lost the argument. He took Japanese and has fun ordering sushi.

It’s not as if learning another language comes with a big payday. In 2002 the Federal Reserve and Harvard put out a study showing those who speak a foreign language earn 2 percent more than those who don’t.

High schools tend to follow colleges’ lead, but maybe that’s beginning to change. I read through all 50 states’ language requirements and only one requires either two years of a foreign language or two years of “computer technology approved for college admission requirements.” Wow. Is that California? No. New York? No. Would you believe Oklahoma? South Dakota and Maryland also have flexible language skill laws. Foolishly, the Common Core State Standards are silent on coding.

The U.S. is falling behind. In 2014 England made computing a part of its national primary curriculum. Estonia had already started coding in its schools as early as first grade. The Netherlands, Belgium, and Finland also have national programs.

Maybe the U.S. can start the ball rolling by requiring colleges and high schools to allow computer languages to count as foreign languages. A handful of high schools already teach the Java computer language using a free tool called Blue J. Nonprofit Code.org exposes students to a visual programming language called Blockly. To compete in this dog-eat-dog world, America should offer Python and Ruby on Rails instead of French and Spanish.

Knowledge is good. Great literature reshuffles the mind. Tough trigonometry problems provide puzzles for the brain. Yet there is no better challenge than writing code that teaches a machine to do exactly what you want. Some will respond, “So you want us to do vocational education?” As if computer programming is akin to auto shop and plumbing. Sorry, that’s a faux argument. Even I remember the French word for bogus.

Let’s face it, the world is headed toward one language anyway. The American-based Germanic-named Uber was originato at the Le Web conference in Paris. In Shanghai, I’ve seen ads on trains and storefronts signs that read “Learn Wall Street English.”

Mr. Cook is right to want more coders, though a tad self-serving as Apple basically sells software wrapped in glass and metal. Same with Code.org, supported by Google and Microsoft. But every company requires coders. Even the formerly blue-collar job of operating machine tools now requires expertise in programming to control them. This will be increasingly true in workerless retail, doctorless medicine, and even teacherless education. Time to modernize the dated curriculum—pronto.

Identifying the Elements of Argument

The roof of the building reads, Argument. The first pillar reads, Thesis. The second pillar reads, Evidence. The third pillar reads, Refutation, and the fourth pillar reads, Concluding Statement.

1. What is this essay’s thesis? Restate it in your own words.

2. List the arguments Kessler presents as evidence to support his thesis.

3. Summarize the main opposing argument the essay identifies. Then, summarize Kessler’s refutation of this argument.

4. Restate the essay’s concluding statement in your own words.

![]()

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

Is a College Education Worth the Money?

Reread the At Issue box on page 23, which summarizes questions raised on both sides of this issue. As the following sources illustrate, reasonable people may disagree about this controversial topic.

As you review the sources, you will be asked to answer some questions and to complete some simple activities. This work will help you understand both the content and the structure of the sources. When you have finished, you will be ready to write an essay in which you take a position on the topic “Is a College Education Worth the Money?”

SOURCES

Ellen Ruppel Shell, “College May Not Be Worth It Anymore,” page 33 |

Marty Nemko, “We Send Too Many Students to College,” page 36 |

Jennie Le, “What Does It Mean to Be a College Grad?,” page 40 |

Bryan Caplan, “The World Might Be Better Off without College for Everyone,” page 42 |

Mary C. Daly and Leila Bengali, “Is It Still Worth Going to College?,” page 48 |

COLLEGE MAY NOT BE WORTH IT ANYMORE

ELLEN RUPPEL SHELL

This essay appeared in the New York Times on May 16, 2018.

Last year, New York became the first state to offer all but its wealthiest residents tuition-free access to its public community colleges and four-year institutions. Though this Excelsior Scholarship didn’t make college completely free, it highlights the power of the pro-college movement in the United States.

Recent decades have brought agreement that higher education is, if not a cure, then at least a protection against underemployment and the inequality it engenders. In 2012, President Barack Obama called a college degree an “economic imperative that every family in America has to be able to afford.”

Americans strove to rise to that challenge: A third of them ages 25 to 29 now hold at least a bachelor’s degree, and many paid heavily for the privilege. By last summer, Americans owed more than $1.3 trillion in student loans, more than two and a half times what they owed a decade earlier.

Young people and their families go into debt because they believe that college will help them in the job market. And on average it does. But this raises a question: Does higher education itself offer that benefit, or are the people who earn bachelor’s degrees already positioned to get higher-paying jobs?

If future income was determined mainly by how much education people received, then you would assume that some higher education would be better than none. But this is often not the case.

People who have dropped out of college—about 40 percent of all who attend—earn only a bit more than do people with only a high school education: $38,376 a year versus $35,256. For many, that advantage is barely enough to cover their student loan debt.

And not all have even that advantage: African-American college dropouts on average earn less than do white Americans with only a high school degree. Meanwhile, low-income students of all races are far more likely to drop out of college than are wealthier students. Even with scholarships or free tuition, these students struggle with hefty fees and living costs, and they pay the opportunity cost of taking courses rather than getting a job.

The value of a college degree also varies depending on the institution bestowing it. The tiny minority of students who attend elite colleges do far better on average than those who attend nonselective ones. Disturbingly, black and Hispanic students are significantly less likely than are white and Asian students to attend elite colleges, even when family income is controlled for. That is, students from wealthy black and Hispanic families have a lower chance of attending an elite college than do students from middle-class white families.

It’s a cruel irony that a college degree is worth less to people who most need a boost: those born poor. This revelation was made by the economists Tim Bartik and Brad Hershbein. Using a body of data, the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, which includes 50 years of interviews with 18,000 Americans, they were able to follow the lives of children born into poor, middle-class, and wealthy families.

They found that for Americans born into middle-class families, a college degree does appear to be a wise investment. Those in this group who received one earned 162 percent more over their careers than those who didn’t.

But for those born into poverty, the results were far less impressive. College graduates born poor earned on average only slightly more than did high school graduates born middle class. And over time, even this small “degree bonus” ebbed away, at least for men: By middle age, male college graduates raised in poverty were earning less than nondegree holders born into the middle class. The scholars conclude, “Individuals from poorer backgrounds may be encountering a glass ceiling that even a bachelor’s degree does not break.”

The authors don’t speculate as to why this is the case, but it seems that students from poor backgrounds have less access to very high-income jobs in technology, finance and other fields. Class and race surely play a role.

We appear to be approaching a time when, even for middle-class students, the economic benefit of a college degree will begin to dim. Since 2000, the growth in the wage gap between high school and college graduates has slowed to a halt; 25 percent of college graduates now earn no more than does the average high school graduate.

Part of the reason is oversupply. Technology increased the demand for educated workers, but that demand has been consistently outpaced by the number of people—urged on by everyone from teachers to presidents—prepared to meet it.

No other nation punishes the “uneducated” as harshly as the United States. Nearly 30 percent of Americans without a high school diploma live in poverty, compared to 5 percent with a college degree, and we infer that this comes from a lack of education. But in 28 other wealthy developed countries, a lack of a high school diploma increases the probability of poverty by less than 5 percent. In these nations, a dearth of education does not predestine citizens for poverty.

It shouldn’t here, either: According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, fewer than 20 percent of American jobs actually require a bachelor’s degree. By 2026, the bureau estimates that this proportion will rise, but only to 25 percent.

Why do employers demand a degree for jobs that don’t require them? Because they can.

What all this suggests is that the college-degree premium may really be a no-college-degree penalty. It’s not necessarily college that gives people the leverage to build a better working life, it’s that not having a degree decreases whatever leverage they might otherwise have.

“No other nation punishes the ’uneducated’ as harshly as the United States.”

This distinction is more than semantic. It is key to understanding the growing chasm between educational attainment and life prospects. For most of us, it’s not our education that determines our employment trajectory but rather where that education positions us in relation to others.

None of this is to suggest that higher education is not desirable: I’ve encouraged my own children to take that path. But while we celebrate the most recent crop of college graduates, we should also acknowledge the many more Americans who will never don a cap and gown. They, too, deserve the chance to prove themselves worthy of good work, and a good life.

![]()

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

1. Shell opens her essay by pointing to New York State’s offer of free college tuition to most residents. Is this an appropriate introduction for the discussion that follows? Why or why not?

2. Paraphrase this essay’s thesis statement by filling in the following template:

Although college may be worth the cost for many students, .

3. Does Shell introduce arguments against her position? If so, where? If not, should she have done so, or is her essay convincing without mention of these counterarguments?

4. In paragraph 9, Shell refers to a study by two economists. How does this study support her position? What other kinds of supporting evidence does she include? Does she need to supply more?

5. In paragraph 18, Shell contrasts the “college-degree premium” with the “no-college-degree penalty.” What is the difference? Why, according to Shell, is this distinction so important?

6. In her conclusion, Shell refers to her own children. Why? Do you think this is a good way for her to end her essay, or do you think she should have ended on a less personal note? Explain.

WE SEND TOO MANY STUDENTS TO COLLEGE

MARTY NEMKO

This undated essay is from MartyNemko.com.

Among my saddest moments as a career counselor is when I hear a story like this: “I wasn’t a good student in high school, but I wanted to prove to myself that I can get a college diploma—I’d be the first one in my family to do it. But it’s been six years and I still have 45 units to go.”

I have a hard time telling such people the killer statistic: According to the U.S. Department of Education, if you graduated in the bottom 40 percent of your high school class and went to college, 76 of 100 won’t earn a diploma, even if given 8½ years. Yet colleges admit and take the money from hundreds of thousands of such students each year!

Even worse, most of those college dropouts leave college having learned little of practical value (see below) and with devastated self-esteem and a mountain of debt. Perhaps worst of all, those people rarely leave with a career path likely to lead to more than McWages. So it’s not surprising that when you hop into a cab or walk into a restaurant, you’re likely to meet workers who spent years and their family’s life savings on college, only to end up with a job they could have done as a high school dropout.

Perhaps yet more surprising, even the high school students who are fully qualified to attend college are increasingly unlikely to derive enough benefit to justify the often six-figure cost and four to eight years it takes to graduate—and only 40 percent of freshmen graduate in four years; 45 percent never graduate at all. Colleges love to trumpet the statistic that, over their lifetimes, college graduates earn more than nongraduates. But that’s terribly misleading because you could lock the college-bound in a closet for four years and they’d earn more than the pool of non-college-bound—they’re brighter, more motivated, and have better family connections. Too, the past advantage of college graduates in the job market is eroding: ever more students are going to college at the same time as ever more employers are offshoring ever more professional jobs. So college graduates are forced to take some very nonprofessional jobs. For example, Jill Plesnarski holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the private ($160,000 published total cost for four years) Moravian College. She had hoped to land a job as a medical research lab tech, but those positions paid so little that she opted for a job at a New Jersey sewage treatment plant. Today, although she’s since been promoted, she must still occasionally wash down the tower that holds raw sewage.

Or take Brian Morris. After completing his bachelor’s degree in liberal arts from the University of California, Berkeley, he was unable to find a decent-paying job, so he went yet deeper into debt to get a master’s degree from the private Mills College. Despite those degrees, the best job he could land was teaching a three-month-long course for $3,000. At that point, Brian was married and had a baby, so to support them, he reluctantly took a job as a truck driver. Now Brian says, “I just have to get out of trucking.”

Colleges are quick to argue that a college education is more about enlightenment than employment. That may be the biggest deception of all. There is a Grand Canyon of difference between what the colleges tout in their brochures and websites and the reality.

“Colleges are businesses, and students are a cost item.”

Colleges are businesses, and students are a cost item while research is a profit center. So colleges tend to educate students in the cheapest way possible: large lecture classes, with small classes staffed by rock-bottom-cost graduate students and, in some cases, even by undergraduate students. Professors who bring in big research dollars are almost always rewarded, while even a fine teacher who doesn’t bring in the research bucks is often fired or relegated to the lowest rung: lecturer.

So, no surprise, in the definitive Your First College Year nationwide survey conducted by UCLA researchers (data collected in 2005, reported in 2007), only 16.4 percent of students were very satisfied with the overall quality of instruction they received and 28.2 percent were neutral, dissatisfied, or very dissatisfied. A follow-up survey of seniors found that 37 percent reported being “frequently bored in class,” up from 27.5 percent as freshmen.

College students may be dissatisfied with instruction, but despite that, do they learn? A 2006 study funded by the Pew Charitable Trusts found that 50 percent of college seniors failed a test that required them to do such basic tasks as interpret a table about exercise and blood pressure, understand the arguments of newspaper editorials, or compare credit card offers. Almost 20 percent of seniors had only basic quantitative skills. For example, the students could not estimate if their car had enough gas to get to the gas station.

What to do? Colleges, which receive billions of tax dollars with minimum oversight, should be held at least as accountable as companies are. For example, when some Firestone tires were defective, the government nearly forced it out of business. Yet year after year, colleges turn out millions of defective products: students who drop out or graduate with far too little benefit for the time and money spent. Yet not only do the colleges escape punishment; they’re rewarded with ever greater taxpayer-funded student grants and loans, which allow colleges to raise their tuitions yet higher.

What should parents and guardians do?

1. If your student’s high school grades and SAT or ACT are in the bottom half of his high school class, resist colleges’ attempts to woo him. Their marketing to your child does not indicate that the colleges believe he will succeed there. Colleges make money whether or not a student learns, whether or not she graduates, and whether or not he finds good employment. If a physician recommended a treatment that cost a fortune and required years of effort without disclosing the poor chances of it working, she’d be sued and lose in any court in the land. But colleges—one of America’s most sacred cows—somehow seem immune.

So let the buyer beware. Consider nondegree options:

§ Apprenticeship programs (a great portal to apprenticeship websites: www.khake.com/page58.html)

§ Short career-preparation programs at community colleges

§ The military

§ On-the-job training, especially at the elbow of a successful small business owner

2. Let’s say your student is in the top half of his high school class and is motivated to attend college by more than the parties, being able to say she went to college, and the piece of paper. Then have her apply to perhaps a dozen colleges. Colleges vary less than you might think, yet financial aid awards can vary wildly. It’s often wise to choose the college that requires you to pay the least cash and take on the smallest loan. College is among the few products where you don’t get what you pay for—price does not indicate quality.

3. If your child is one of the rare breed who, on graduating high school, knows what he wants to do and isn’t unduly attracted to college academics or the Animal House environment that college dorms often are, then take solace in the fact that in deciding to forgo college, he is preceded by scores of others who have successfully taken that noncollege road less traveled. Examples: the three most successful entrepreneurs in the computer industry, Bill Gates, Michael Dell, and Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak, all do not have a college degree. Here are some others: Malcolm X, Rush Limbaugh, Barbra Streisand, PBS NewsHour’s Nina Totenberg, Tom Hanks, Maya Angelou, Ted Turner, Ellen DeGeneres, former governor Jesse Ventura, IBM founder Thomas Watson, architect Frank Lloyd Wright, former Israeli president David Ben-Gurion, Woody Allen, Warren Beatty, Domino’s pizza chain founder Tom Monaghan, folksinger Joan Baez, director Quentin Tarantino, ABC-TV’s Peter Jennings, Wendy’s founder Dave Thomas, Thomas Edison, Blockbuster Video founder and owner of the Miami Dolphins Wayne Huizenga, William Faulkner, Jane Austen, McDonald’s founder Ray Kroc, Oracle founder Larry Ellison, Henry Ford, cosmetics magnate Helena Rubinstein, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Graham Bell, Coco Chanel, Walter Cronkite, Walt Disney, Bob Dylan, Leonardo DiCaprio, cookie maker Debbi Fields, Sally Field, Jane Fonda, Buckminster Fuller, DreamWorks cofounder David Geffen, Roots author Alex Haley, Ernest Hemingway, Dustin Hoffman, famed anthropologist Richard Leakey, airplane inventors Wilbur and Orville Wright, Madonna, satirist H. L. Mencken, Martina Navratilova, Rosie O’Donnell, Nathan Pritikin (Pritikin diet), chef Wolfgang Puck, Robert Redford, oil billionaire John D. Rockefeller, Eleanor Roosevelt, NBC mogul David Sarnoff, and seven U.S. presidents from Washington to Truman.

4. College is like a chain saw. Only in certain situations is it the right tool. Encourage your child to choose the right tool for her post—high school experience.

![]()

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

1. Which of the following statements best summarizes Nemko’s position? Why?

§ “We Send Too Many Students to College” (title)

§ “There is a Grand Canyon of difference between what the colleges tout in their brochures and websites and the reality” (para. 6).

§ “Colleges, which receive billions of tax dollars with minimum oversight, should be held at least as accountable as companies are” (10).

§ “College is like a chain saw. Only in certain situations is it the right tool” (16).

2. Where does Nemko support his thesis with appeals to logic? Where does he appeal to the emotions? Where does he use an appeal to authority? (Refer to the discussions of logos, pathos, and ethos on pages 14—18 if necessary.) Which of these three kinds of appeals do you find the most convincing? Why?

3. List the arguments Nemko uses to support his thesis in paragraphs 2—4.

4. In paragraph 4, Nemko says, “Colleges love to trumpet the statistic that, over their lifetimes, college graduates earn more than nongraduates.” In paragraph 6, he says, “Colleges are quick to argue that a college education is more about enlightenment than employment.” How does he refute these two opposing arguments?

5. Nemko draws an analogy between colleges and businesses, identifying students as a “cost item” (7). Does this analogy—including his characterization of weak students as “defective products” (10)—work for you? Why or why not?

6. What specific solutions does Nemko propose for the problem he identifies? To whom does he address these suggestions—and, in fact, his entire argument?

7. Reread paragraph 15. Do you think the list of successful people who do not hold college degrees is convincing support for Nemko’s position? What kind of appeal does this paragraph make? How might you refute its argument?

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE A COLLEGE GRAD?

JENNIE LE

This personal essay is from talk.onevietnam.org, where it appeared on May 9, 2011.

After May 14th, I will be a college graduate. By fall, there will be no more a cappella rehearsals, no more papers or exams, no more sleepless nights, no more weekday drinking, no more 1 a.m. milk tea runs, no more San Francisco Bay Area exploring. I won’t be with the people I now see daily. I won’t have the same job with the same awesome boss. I won’t be singing under Sproul every Monday. I won’t be booked with weekly gigs that take me all over California. I won’t be lighting another VSA Culture Show.

I will also have new commitments: weekly dinner dates with my mom, brother/sister time with my other two brothers, job hunting and career building, car purchasing and maintenance. In essence, my life will be—or at least feel—completely different. From what college alumni have told me, I will soon miss my college days after they are gone.

“Nowadays, holding a college degree (or two) seems like the norm.”

But in the bigger picture, outside of the daily tasks, what does it mean to hold a college degree? My fellow graduating coworker and I discussed the importance (or lack thereof) of our college degrees: while I considered hanging up my two diplomas, she believed that having a bachelor’s was so standard and insubstantial, only a professional degree is worth hanging up and showing off. Nowadays, holding a college degree (or two) seems like the norm; it’s not a very outstanding feat.

However, I’d like to defend the power of earning a college degree. Although holding a degree isn’t as powerful as it was in previous decades, stats still show that those who earn bachelor’s degrees are likely to earn twice as much as those who don’t. Also, only 27 percent of Americans can say they have a bachelor’s degree or higher. Realistically, having a college degree will likely mean a comfortable living and the opportunity to move up at work and in life.

Personally, my degrees validate my mother’s choice to leave Vietnam. She moved here for opportunity. She wasn’t able to attend college here or in Vietnam or choose her occupation. But her hard work has allowed her children to become the first generation of Americans in the family to earn college degrees: she gave us the ability to make choices she wasn’t privileged to make. Being the fourth and final kid to earn my degree in my family, my mom can now boast about having educated children who are making a name for themselves (a son who is a computer-superstar, a second son and future dentist studying at UCSF, another son who is earning his MBA and manages at Mattel, and a daughter who is thankful to have three brothers to mooch off of).

For me, this degree symbolizes my family being able to make and take the opportunities that we’ve been given in America, despite growing up with gang members down my street and a drug dealer across from my house. This degree will also mean that my children will have more opportunities because of my education, insight, knowledge, and support.

Even though a college degree isn’t worth as much as it was in the past, it still shows that I—along with my fellow graduates and the 27 percent of Americans with a bachelor’s or higher—will have opportunities unheard of a generation before us, showing everyone how important education is for our lives and our futures.

![]()

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

1. What purpose do the first two paragraphs of this essay serve? Do you think they are necessary? Do you think they are interesting? How else might Le have opened her essay?

2. Where does Le state her thesis? Do you think she should have stated it more forcefully? Can you suggest a more effectively worded thesis statement for this essay?

3. In paragraph 3, Le summarizes an opposing argument. What is this argument? How does she refute it? Can you think of other arguments against her position that she should have addressed?

4. In paragraphs 5—6, Le includes an appeal to the emotions. Does she offer any other kind of supporting evidence? If so, where? What other kinds of evidence do you think she should include? Why?

5. Echoing a point she made in paragraph 4, Le begins her conclusion with “Even though a college degree isn’t worth as much as it was in the past, . . .” Does this concession undercut her argument, or is the information presented in paragraph 4 enough to address this potential problem?

THE WORLD MIGHT BE BETTER OFF WITHOUT COLLEGE FOR EVERYONE

BRYAN CAPLAN

This essay appeared in the January/February 2018 issue of The Atlantic.

I have been in school for more than 40 years. First preschool, kindergarten, elementary school, junior high, and high school. Then a bachelor’s degree at UC Berkeley, followed by a doctoral program at Princeton. The next step was what you could call my first “real” job—as an economics professor at George Mason University.

Thanks to tenure, I have a dream job for life. Personally, I have no reason to lash out at our system of higher education. Yet a lifetime of experience, plus a quarter century of reading and reflection, has convinced me that it is a big waste of time and money. When politicians vow to send more Americans to college, I can’t help gasping, “Why? You want us to waste even more?”

How, you may ask, can anyone call higher education wasteful in an age when its financial payoff is greater than ever? The earnings premium for college graduates has rocketed to 73 percent—that is, those with a bachelor’s degree earn, on average, 73 percent more than those who have only a high school diploma, up from about 50 percent in the late 1970s. The key issue, however, isn’t whether college pays, but why. The simple, popular answer is that schools teach students useful job skills. But this dodges puzzling questions.

First and foremost: From kindergarten on, students spend thousands of hours studying subjects irrelevant to the modern labor market. Why do English classes focus on literature and poetry instead of business and technical writing? Why do advanced-math classes bother with proofs almost no student can follow? When will the typical student use history? Trigonometry? Art? Music? Physics? Latin? The class clown who snarks “What does this have to do with real life?” is onto something.

The disconnect between college curricula and the job market has a banal explanation: Educators teach what they know—and most have as little firsthand knowledge of the modern workplace as I do. Yet this merely complicates the puzzle. If schools aim to boost students’ future income by teaching job skills, why do they entrust students’ education to people so detached from the real world? Because, despite the chasm between what students learn and what workers do, academic success is a strong signal of worker productivity.

Suppose your law firm wants a summer associate. A law student with a doctorate in philosophy from Stanford applies. What do you infer? The applicant is probably brilliant, diligent, and willing to tolerate serious boredom. If you’re looking for that kind of worker—and what employer isn’t?—you’ll make an offer, knowing full well that nothing the philosopher learned at Stanford will be relevant to this job.

The labor market doesn’t pay you for the useless subjects you master; it pays you for the preexisting traits you signal by mastering them. This is not a fringe idea. Michael Spence, Kenneth Arrow, and Joseph Stiglitz—all Nobel laureates in economics—made seminal contributions to the theory of educational signaling. Every college student who does the least work required to get good grades silently endorses the theory. But signaling plays almost no role in public discourse or policy making. As a society, we continue to push ever larger numbers of students into ever higher levels of education. The main effect is not better jobs or greater skill levels, but a credentialist arms race.

Lest I be misinterpreted, I emphatically affirm that education confers some marketable skills, namely literacy and numeracy. Nonetheless, I believe that signaling accounts for at least half of college’s financial reward, and probably more.

Most of the salary payoff for college comes from crossing the graduation finish line. Suppose you drop out after a year. You’ll receive a salary bump compared with someone who’s attended no college, but it won’t be anywhere near 25 percent of the salary premium you’d get for a four-year degree. Similarly, the premium for sophomore year is nowhere near 50 percent of the return on a bachelor’s degree, and the premium for junior year is nowhere near 75 percent of that return. Indeed, in the average study, senior year of college brings more than twice the pay increase of freshman, sophomore, and junior years combined. Unless colleges delay job training until the very end, signaling is practically the only explanation. This in turn implies a mountain of wasted resources—time and money that would be better spent preparing students for the jobs they’re likely to do.

The conventional view—that education pays because students learn— assumes that the typical student acquires, and retains, a lot of knowledge. She doesn’t. Teachers often lament summer learning loss: Students know less at the end of summer than they did at the beginning. But summer learning loss is only a special case of the problem of fade-out: Human beings have trouble retaining knowledge they rarely use. Of course, some college graduates use what they’ve learned and thus hold on to it—engineers and other quantitative types, for example, retain a lot of math. But when we measure what the average college graduate recalls years later, the results are discouraging, to say the least.

In 2003, the United States Department of Education gave about 18,000 Americans the National Assessment of Adult Literacy. The ignorance it revealed is mind-numbing. Fewer than a third of college graduates received a composite score of “proficient”—and about a fifth were at the “basic” or “below basic” level. You could blame the difficulty of the questions—until you read them. Plenty of college graduates couldn’t make sense of a table explaining how an employee’s annual health-insurance costs varied with income and family size, or summarize the work-experience requirements in a job ad, or even use a newspaper schedule to find when a television program ended. Tests of college graduates’ knowledge of history, civics, and science have had similarly dismal results.

Of course, college students aren’t supposed to just download facts; they’re supposed to learn how to think in real life. How do they fare on this count? The most focused study of education’s effect on applied reasoning, conducted by Harvard’s David Perkins in the mid-1980s, assessed students’ oral responses to questions designed to measure informal reasoning, such as “Would a proposed law in Massachusetts requiring a five-cent deposit on bottles and cans significantly reduce litter?” The benefit of college seemed to be zero: Fourth-year students did no better than first-year students.

Other evidence is equally discouraging. One researcher tested Arizona State University students’ ability to “apply statistical and methodological concepts to reasoning about everyday-life events.” In the researcher’s words:

Of the several hundred students tested, many of whom had taken more than six years of laboratory science … and advanced mathematics through calculus, almost none demonstrated even a semblance of acceptable methodological reasoning.

Those who believe that college is about learning how to learn should expect students who study science to absorb the scientific method, then habitually use it to analyze the world. This scarcely occurs.

College students do hone some kinds of reasoning that are specific to their major. One ambitious study at the University of Michigan tested natural-science, humanities, and psychology and other social-science majors on verbal reasoning, statistical reasoning, and conditional reasoning during the first semester of their first year. When the same students were retested the second semester of their fourth year, each group had sharply improved in precisely one area. Psychology and other social-science majors had become much better at statistical reasoning. Natural-science and humanities majors had become much better at conditional reasoning—analyzing “if … then” and “if and only if” problems. In the remaining areas, however, gains after three and a half years of college were modest or nonexistent. The takeaway: Psychology students use statistics, so they improve in statistics; chemistry students rarely encounter statistics, so they don’t improve in statistics. If all goes well, students learn what they study and practice.

Actually, that’s optimistic. Educational psychologists have discovered that much of our knowledge is “inert.” Students who excel on exams frequently fail to apply their knowledge to the real world. Take physics. As the Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner writes,

Students who receive honor grades in college-level physics courses are frequently unable to solve basic problems and questions encountered in a form slightly different from that on which they have been formally instructed and tested.

The same goes for students of biology, mathematics, statistics, and, I’m embarrassed to say, economics. I try to teach my students to connect lectures to the real world and daily life. My exams are designed to measure comprehension, not memorization. Yet in a good class, four test-takers out of 40 demonstrate true economic understanding.

Economists educational bean counting can come off as annoyingly narrow. Noneconomists—also known as normal human beings—lean holistic: We can’t measure education’s social benefits solely with test scores or salary premiums. Instead we must ask ourselves what kind of society we want to live in—an educated one or an ignorant one?

Normal human beings make a solid point: We can and should investigate education’s broad social implications. When humanists consider my calculations of education’s returns, they assume I’m being a typical cynical economist, oblivious to the ideals so many educators hold dear. I am an economist and I am a cynic, but I’m not a typical cynical economist. I’m a cynical idealist. I embrace the ideal of transformative education. I believe wholeheartedly in the life of the mind. What I’m cynical about is people.

I’m cynical about students. The vast majority are philistines. I’m cynical about teachers. The vast majority are uninspiring. I’m cynical about “deciders”—the school officials who control what students study. The vast majority think they’ve done their job as long as students comply.

Those who search their memory will find noble exceptions to these sad rules. I have known plenty of eager students and passionate educators, and a few wise deciders. Still, my 40 years in the education industry leave no doubt that they are hopelessly outnumbered. Meritorious education survives but does not thrive.

Indeed, today’s college students are less willing than those of previous generations to do the bare minimum of showing up for class and temporarily learning whatever’s on the test. Fifty years ago, college was a full-time job. The typical student spent 40 hours a week in class or studying. Effort has since collapsed across the board. “Full time” college students now average 27 hours of academic work a week—including just 14 hours spent studying.

What are students doing with their extra free time? Having fun. As Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa frostily remark in their 2011 book, Academically Adrift,

If we presume that students are sleeping eight hours a night, which is a generous assumption given their tardiness and at times disheveled appearance in early morning classes, that leaves 85 hours a week for other activities.

Arum and Roksa cite a study finding that students at one typical college spent 13 hours a week studying, 12 hours “socializing with friends,” 11 hours “using computers for fun,” eight hours working for pay, six hours watching TV, six hours exercising, five hours on “hobbies,” and three hours on “other forms of entertainment.” Grade inflation completes the idyllic package by shielding students from negative feedback. The average GPA is now 3.2.

What does this mean for the individual student? Would I advise an academically well-prepared 18-year-old to skip college because she won’t learn much of value? Absolutely not. Studying irrelevancies for the next four years will impress future employers and raise her income potential. If she tried to leap straight into her first white-collar job, insisting, “I have the right stuff to graduate, I just choose not to,” employers wouldn’t believe her. To unilaterally curtail your education is to relegate yourself to a lower-quality pool of workers. For the individual, college pays.

This does not mean, however, that higher education paves the way to general prosperity or social justice. When we look at countries around the world, a year of education appears to raise an individual’s income by 8 to 11 percent. By contrast, increasing education across a country’s population by an average of one year per person raises the national income by only 1 to 3 percent. In other words, education enriches individuals much more than it enriches nations.

How is this possible? Credential inflation: As the average level of education rises, you need more education to convince employers you’re worthy of any specific job. One research team found that from the early 1970s through the mid-1990s, the average education level within 500 occupational categories rose by 1.2 years. But most of the jobs didn’t change much over that span—there’s no reason, except credential inflation, why people should have needed more education to do them in 1995 than in 1975. What’s more, all American workers’ education rose by 1.5 years in that same span—which is to say that a great majority of the extra education workers received was deployed not to get better jobs, but to get jobs that had recently been held by people with less education.

As credentials proliferate, so do failed efforts to acquire them. Students can and do pay tuition, kill a year, and flunk their finals. Any respectable verdict on the value of education must account for these academic bankruptcies. Failure rates are high, particularly for students with low high school grades and test scores; all told, about 60 percent of full-time college students fail to finish in four years. Simply put, the push for broader college education has steered too many students who aren’t cut out for academic success onto the college track.

“Ignorance of the future is no reason to prepare students for occupations they almost surely won’t have.”

The college-for-all mentality has fostered neglect of a realistic substitute: vocational education. It takes many guises—classroom training, apprenticeships and other types of on-the-job training, and straight-up work experience—but they have much in common. All vocational education teaches specific job skills, and all vocational education revolves around learning by doing, not learning by listening. Research, though a bit sparse, suggests that vocational education raises pay, reduces unemployment, and increases the rate of high school completion.

Defenders of traditional education often appeal to the obscurity of the future. What’s the point of prepping students for the economy of 2018, when they’ll be employed in the economy of 2025 or 2050? But ignorance of the future is no reason to prepare students for occupations they almost surely won’t have—and if we know anything about the future of work, we know that the demand for authors, historians, political scientists, physicists, and mathematicians will stay low. It’s tempting to say that students on the college track can always turn to vocational education as a Plan B, but this ignores the disturbing possibility that after they crash, they’ll be too embittered to go back and learn a trade. The vast American underclass shows that this disturbing possibility is already our reality.

Education is so integral to modern life that we take it for granted. Young people have to leap through interminable academic hoops to secure their place in the adult world. My thesis, in a single sentence: Civilized societies revolve around education now, but there is a better—indeed, more civilized—way. If everyone had a college degree, the result would be not great jobs for all, but runaway credential inflation. Trying to spread success with education spreads education but not success.

![]()

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

1. Why does Caplan begin his essay with a summary of his own educational and employment history? Is this introductory strategy an appeal to logos, ethos, or pathos? (See pages 19—21 for an explanation of these terms.)

2. Caplan identifies a number of shortcomings of today’s college students—and of our higher education system in general. What problems does he identify? Where does he seem to place the blame for these problems? Does he offer solutions? If so, where?

3. Where does Caplan cite research studies? How does he use these studies to support his conclusions about the value of a college education?

4. Where does Caplan use personal experience as evidence in support of his points? Do you find this kind of evidence convincing here? Why or why not?

5. Do you think Caplan’s use of the first-person pronoun I throughout strengthens or weakens his argument? Explain you conclusion.

6. In paragraph 7, Caplan says, “The labor market doesn’t pay you for the useless subjects you master; it pays you for the preexisting traits you signal by mastering them.” What does he mean? Do you think he is correct about the importance of what he calls “signaling” (para. 8)? Why or why not?

7. In paragraphs 4 and 10, Caplan summarizes arguments against his position. How does he refute these counterarguments? Does he include other arguments against his position? If so, where?

8. In paragraphs 23—24, Caplan says, “For the individual, college pays. This does not mean, however, that higher education paves the way to general prosperity or social justice.” What point is he making here about the value of a college education?

9. What is “credential inflation” (29)? How is it related to what Caplan calls his “thesis, in a single sentence”? Do you think this “thesis” is actually the essay’s main idea? Explain.

IS IT STILL WORTH GOING TO COLLEGE?

MARY C. DALY AND LEILA BENGALI

This economic letter was originally posted by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco at www.frbsf.org, where it appeared on May 5, 2014.

Media accounts documenting the rising cost of a college education and relatively bleak job prospects for new college graduates have raised questions about whether a four-year college degree is still the right path for the average American. In this Economic Letter, we examine whether going to college remains a worthwhile investment. Using U.S. survey data, we compare annual labor earnings of college graduates with those of individuals with only a high school diploma. The data show college graduates outearn their high school counterparts as much as in past decades. Comparing the earnings benefits of college with the costs of attending a four-year program, we find that college is still worth it. This means that, for the average student, tuition costs for the majority of college education opportunities in the United States can be recouped by age 40, after which college graduates continue to earn a return on their investment in the form of higher lifetime wages.

Earnings Outcomes by Educational Attainment

A common way to track the value of going to college is to estimate a college earnings premium, which is the amount college graduates earn relative to high school graduates. We measure earnings for each year as the annual labor income for the prior year, adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index (CPI-U), reported in 2011 dollars. The earnings premium refers to the difference between average annual labor income for high school and college graduates. We use data on household heads and partners from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID). The PSID is a longitudinal study that follows individuals living in the United States over a long time span. The survey began in 1968 and now has more than 40 years of data including educational attainment and labor market income. To focus on the value of a college degree relative to less education, we exclude people with more than a four-year degree.

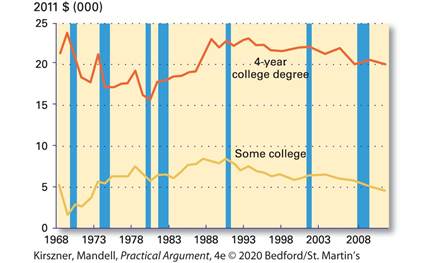

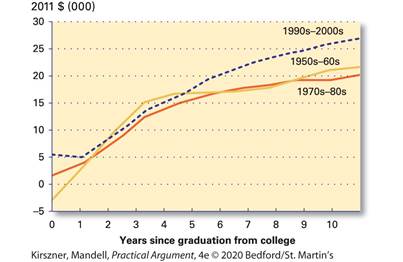

Figure 1 shows the earnings premium relative to high school graduates for individuals with a four-year college degree and for those with some college but no four-year degree. The payoff from a degree is apparent. Although the premium has fluctuated over time, at its lowest in 1980 it was about $15,750, meaning that individuals with a four-year college degree earned about 43 percent more on average than those with only a high school degree. In 2011, the latest data available in our sample, college graduates earned on average about $20,050 (61 percent) more per year than high school graduates. Over the entire sample period the college earnings premium has averaged about $20,300 (57 percent) per year. The premium is much smaller, although not zero, for workers with some college but no four-year degree.

Figure 1: Earnings Premium over High School Education

Data from: PSID and authors’ calculations. Premium defined as difference in mean annual labor income. Blue bars denote National Bureau of Economic Research recession dates.

The approximate data are as follows.

In 1969, the 4-year college degree premium was approximately 21,000 dollars and increased to around 24,000 in 1970 and then after a few dips and spikes, reached the lowest at 15,750 in 1980, and then gradually increased reaching approximately 23,900 in 1988, and continuing with minimal fluctuation and finally reaching 20,050 dollars in 2011.

The graph for Some college starts at 5000 dollars in 1968 and decreases sharply reaching approximately 2000 dollars in 1970. The graph then rises gradually making small increases and decreases and reaching the peak at around 8500 in 1991. The curve then gradually zigzags downward almost going below 5000 dollars in 2011.

A potential shortcoming of the results in Figure 1 is that they combine the earnings outcomes for all college graduates, regardless of when they earned a degree. This can be misleading if the value from a college education has varied across groups from different graduation decades, called “cohorts.” To examine whether the college earnings premium has changed from one generation to the next, we take advantage of the fact that the PSID follows people over a long period of time, which allows us to track college graduation dates and subsequent earnings.

Using these data we compute the college earnings premium for three college graduate cohorts, namely those graduating in the 1950s—60s, the 1970s—80s, and the 1990s—2000s. The premium measures the difference between the average annual earnings of college graduates and high school graduates over their work lives. To account for the fact that high school graduates gain work experience during the four years they are not in college, we compare earnings of college graduates in each year since graduation to earnings of high school graduates in years since graduation plus four. We also adjust the estimates for any large annual fluctuations by using a three-year centered moving average, which plots a specific year as the average of earnings from that year, the year before, and the year after.

Figure 2 shows that the college earnings premium has risen consistently across cohorts. Focusing on the most recent college graduates (1990s—2000s) there is little evidence that the value of a college degree has declined over time, and it has even risen somewhat for graduates five to ten years out of school.

Figure 2: College Earnings Premium by Graduation Decades

Data from: PSID and authors’ calculations. Premium defined as difference in mean annual labor income of college graduates in each year since graduation and earnings of high school graduates in years since graduation plus four. Values are three-year centered moving averages of annual premiums.

The approximate data are as follows. The graph for 1950s to 60s starts at around minus 3 at zero years since graduation from college and slopes upward reaching 15,000 dollars in the third year since graduation from college. The curve then remains almost constant till around 8 years since graduation. It then gradually increases crossing 20,000 dollars after 10 years since graduation from college.

The graph for 1970s to 80s starts approximately at 1,000 dollars at zero years since graduation from college and gradually increases reaching approximately 12,000 dollars after 3 years since graduation from college and continues to increase till 9 years since graduation reaching almost 19,900 dollars. The graph then dips to approximately 19,700 after the ninth year and then increases reaching 20,000 after the tenth year since graduation from college.

The graph for 1990s to 2000s starts approximately at 5500 dollars at zero years since graduation from college and dips to 5,000 dollars after one year since graduation from college. The curve then steeps upward reaching 15,000 dollars at approximately 4 years since graduation. The curve again slopes upward reaching approximately 27,000 after 10 years since graduation from college.

The figure also shows that the gap in earnings between college and high school graduates rises over the course of a worker’s life. Comparing the earnings gap upon graduation with the earnings gap 10 years out of school illustrates this. For the 1990s—2000s cohort the initial gap was about $5,400, and in 10 years this gap had risen to about $26,800. Other analysis confirms that college graduates start with higher annual earnings, indicated by an initial earnings gap, and experience more rapid growth in earnings than members of their age cohort with only a high school degree. This evidence tells us that the value of a college education rises over a worker’s life.

Of course, some of the variation in earnings between those with and without a college degree could reflect other differences. Still, these simple estimates are consistent with a large and rigorous literature documenting the substantial premium earned by college graduates (Barrow and Rouse 2005, Card 2001, Goldin and Katz 2008, and Cunha, Karahan, and Soares 2011). The main message from these and similar calculations is that on average the value of college is high and not declining over time.

Finally, it is worth noting that the benefits of college over high school also depend on employment, where college graduates also have an advantage. High school graduates consistently face unemployment rates about twice as high as those for college graduates, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. When the labor market takes a turn for the worse, as during recessions, workers with lower levels of education are especially hard-hit (Hoynes, Miller, and Schaller 2012). Thus, in good times and in bad, those with only a high school education face a lower probability of employment, on top of lower average earnings once employed.

The Cost of College

“Although the value of college is apparent, deciding whether it is worthwhile means weighing the value against the costs of attending.”

Although the value of college is apparent, deciding whether it is worthwhile means weighing the value against the costs of attending. Indeed, much of the debate about the value of college stems not from the lack of demonstrated benefit but from the overwhelming cost. A simple way to measure the costs against the benefits is to find the breakeven amount of annual tuition that would make the average student indifferent between going to college versus going directly to the workforce after high school.

To simplify the analysis, we assume that college lasts four years, students enter college directly from high school, annual tuition is the same all four years, and attendees have no earnings while in school. To focus on more recent experiences yet still have enough data to measure earnings since graduation, we use the last two decades of graduates (1990s and 2000s) and again smooth our estimates by using three-year centered moving averages.

We calculate the cost of college as four years of tuition plus the earnings missed from choosing not to enter the workforce. To estimate what students would have received had they worked, we use the average annual earnings of a high school graduate zero, one, two, and three years since graduation.

To determine the benefit of going to college, we use the difference between the average annual earnings of a college graduate with zero, one, two, three, and so on, years of experience and the average annual earnings of a high school graduate with four, five, six, seven, and so on years of experience. Because the costs of college are paid today but the benefits accrue over many future years when a dollar earned will be worth less, we discount future earnings by 6.67 percent, which is the average rate on an AAA bond from 1990 to 2011.

With these pieces in place, we can calculate the breakeven amount of tuition for the average college graduate for any number of years; allowing more time to regain the costs will increase our calculated tuition ceiling.

If we assume that accumulated earnings between college graduates and nongraduates will equalize 20 years after graduating from high school (at age 38), the resulting estimate for breakeven annual tuition would be about $21,200. This amount may seem low compared to the astronomical costs for a year at some prestigious institutions; however, about 90 percent of students at public four-year colleges and about 20 percent of students at private nonprofit four-year colleges faced lower annual inflation-adjusted published tuition and fees in 2013—14 (College Board 2013). Although some colleges cost more, there is no definitive evidence that they produce far superior results for all students (Dale and Krueger 2011).

Table 1 shows more examples of maximum tuitions and the corresponding percent of students who pay less for different combinations of breakeven years and discount rates. Note that the tuition estimates are those that make the costs and benefits of college equal. So, tuition amounts lower than our estimates make going to college strictly better in terms of earnings than not going to college.

|

Table 1: Maximum Tuitions by Breakeven Age and Discount Rates |

||

|

Breakeven age |

||

|

33 (15 yrs after HS) 38 (20 yrs after HS) |

||

Accumulated earnings with constant annual premium |

$880,134 |

$830,816 |

Discount rate |

Maximum tuition (% students paying less) |

|

5% |

$14,385 |

$29,111 |

(53—62%) |

(82—85%) |

|

6.67%i |

$9,869 |

$21,217 |

(37—53%) |

(69—73%) |

|

9% |

$4,712 |

$12,653 |

(0—6%) |

(53—62%) |

|

|

iAverage AAA bond rate 1990—2011 (rounded; Moody’s). |

||

Data from: PSID, College Board, and authors’ calculations. Premia held constant 15 or 20 years after high school (HS) graduation. Percent range gives lower and upper bounds of the percent of full-time undergraduates at four-year institutions who faced lower annual inflation-adjusted published tuition and fees in 2013—14.

Although other individual factors might affect the net value of a college education, earning a degree clearly remains a good investment for most young people. Moreover, once that investment is paid off, the extra income from the college earnings premium continues as a net gain to workers with a college degree. If we conservatively assume that the annual premium stays around $28,650, which is the premium 20 years after high school graduation for graduates in the 1990s—2000s, and accrues until the Social Security normal retirement age of 67, the college graduate would have made about $830,800 more than the high school graduate. These extra earnings can be spent, saved, or reinvested to pay for the college tuition of the graduate’s children.

Conclusion

Although there are stories of people who skipped college and achieved financial success, for most Americans the path to higher future earnings involves a four-year college degree. We show that the value of a college degree remains high, and the average college graduate can recover the costs of attending in less than 20 years. Once the investment is paid for, it continues to pay dividends through the rest of the worker’s life, leaving college graduates with substantially higher lifetime earnings than their peers with a high school degree. These findings suggest that redoubling the efforts to make college more accessible would be time and money well spent.

References

· Barrow, L., and Rouse, C. E. (2005). “Does college still pay?” The Economist’s Voice 2(4), pp. 1—8.

· Card, D. (2001). “Estimating the return to schooling: progress on some persistent econometric problems.” Econometrica 69(5), pp. 1127—1160.

· College Board. (2013). “Trends in College Pricing 2013.”