Practical argument: A text and anthology - Laurie G. Kirszner, Stephen R. Mandell 2019

Understanding logic and recognizing logical fallacies

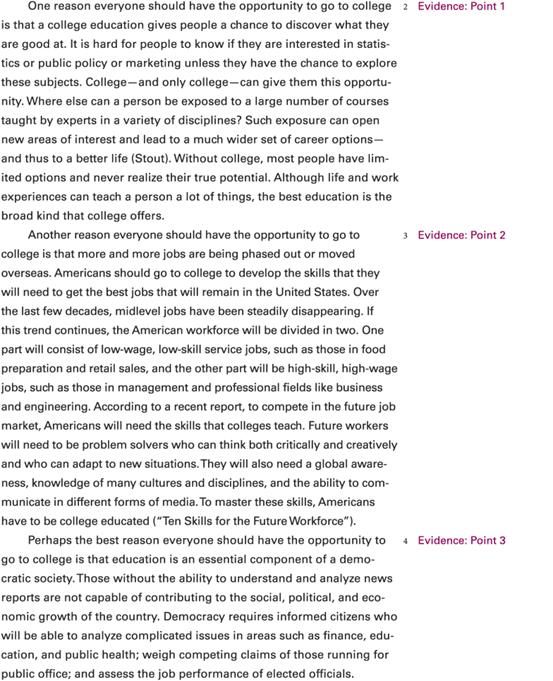

Reading and responding to arguments

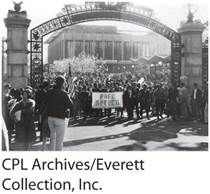

The photo shows a large crowd of student protestors marching through the college gates holding a banner reading, Free Speech. One of the students is holding the U. S. flag.

AT ISSUE

How Free Should Free Speech Be?

Ask almost anyone what makes a society free and one of the answers will be free speech. The free expression of ideas is integral to freedom itself, and protecting that freedom is part of a democratic government’s job.

But what happens when those ideas are offensive, or even dangerous? If free speech has limits, is it still free? When we consider the question abstractly, it’s very easy to say no. After all, there is no shortage of historical evidence linking censorship with tyranny. When we think of limiting free speech, we think of totalitarian regimes, like Nazi Germany. On the other hand, what if the people arguing for the right to be heard are Nazis themselves? In places like Israel and France, where the legacy of Nazi Germany is still all too real, there are some things you simply cannot say. Anti-Semitic language is considered “hate speech,” and those who perpetuate it face stiff fines, if not imprisonment. In the United States, speech—even speech that many would consider “hate speech”—is explicitly protected by the First Amendment of the Constitution. Nonetheless, many colleges and universities have sought to combat discrimination and harassment by instituting speech codes that prohibit speech that they deem inappropriate.

On American college campuses, freedom of speech has traditionally been considered fundamental to a liberal education. Indeed, encountering ideas that make you feel uncomfortable is a necessary part of a college education. But the question of free speech is easy to answer when it’s theoretical: when the issue is made tangible by racist language or by a discussion of a traumatic experience, it becomes much more difficult to navigate. Should minorities be forced to listen to racists spew hate? Should a rape survivor have to sit through a discussion of rape in American literature? If you penalize a person for saying something hateful, will other subjects soon become off-limits for discussion?

Later in this chapter, you will be asked to think more about this issue. You will be given several sources to consider and asked to write a logical argument that takes a position on how free free speech should be.

The word logic comes from the Greek word logos, roughly translated as “word,” “thought,” “principle,” or “reason.” Logic is concerned with the principles of correct reasoning. By studying logic, you learn the rules that determine the validity of arguments. In other words, logic enables you to tell whether a conclusion correctly follows from a set of statements or assumptions.

Why should you study logic? One answer is that logic enables you to make valid points and draw sound conclusions. An understanding of logic also enables you to evaluate the arguments of others. When you understand the basic principles of logic, you know how to tell the difference between a strong argument and a weak argument—between one that is well reasoned and one that is not. This ability can help you cut through the tangle of jumbled thought that characterizes many of the arguments you encounter daily—on television, radio, and the internet; in the press; and from friends. Finally, logic enables you to communicate clearly and forcefully. Understanding the characteristics of good arguments helps you to present your own ideas in a coherent and even compelling way.

Specific rules determine the criteria you use to develop (and to evaluate) arguments logically. For this reason, you should become familiar with the basic principles of deductive and inductive reasoning—two important ways information is organized in argumentative essays. (Keep in mind that a single argumentative essay might contain both deductive reasoning and inductive reasoning. For the sake of clarity, however, we will discuss them separately.)

What Is Deductive Reasoning?

Most of us use deductive reasoning every day—at home, in school, on the job, and in our communities—usually without even realizing it.

Deductive reasoning begins with premises—statements or assumptions on which an argument is based or from which conclusions are drawn. Deductive reasoning moves from general statements, or premises, to specific conclusions. The process of deduction has traditionally been illustrated with a syllogism, which consists of a major premise, a minor premise, and a conclusion:

MAJOR PREMISE

All Americans are guaranteed freedom of speech by the Constitution.

MINOR PREMISE

Sarah is an American.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, Sarah is guaranteed freedom of speech.

A syllogism begins with a major premise—a general statement that relates two terms. It then moves to a minor premise—an example of the statement that was made in the major premise. If these two premises are linked correctly, a conclusion that is supported by the two premises logically follows. (Notice that the conclusion in the syllogism above contains no terms that do not appear in the major and minor premises.) The strength of deductive reasoning is that if readers accept the major and minor premises, the conclusion must necessarily follow.

Thomas Jefferson used deductive reasoning in the Declaration of Independence (see p. 732). When, in 1776, the Continental Congress asked him to draft this document, Jefferson knew that he had to write a powerful argument that would convince the world that the American colonies were justified in breaking away from England. He knew how compelling a deductive argument could be, and so he organized the Declaration of Independence to reflect the traditional structure of deductive logic. It contains a major premise, a minor premise (supported by evidence), and a conclusion. Expressed as a syllogism, here is the argument that Jefferson used:

MAJOR PREMISE

When a government oppresses people, the people have a right to rebel against that government.

MINOR PREMISE

The government of England oppresses the American people.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, the American people have the right to rebel against the government of England.

In practice, deductive arguments are more complicated than the simple three-part syllogism suggests. Still, it is important to understand the basic structure of a syllogism because a syllogism enables you to map out your argument, to test it, and to see if it makes sense.

Constructing Sound Syllogisms

A syllogism is valid when its conclusion follows logically from its premises. A syllogism is true when the premises are consistent with the facts. To be sound, a syllogism must be both valid and true.

Consider the following valid syllogism:

MAJOR PREMISE

All state universities must accommodate disabled students.

MINOR PREMISE

UCLA is a state university.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, UCLA must accommodate disabled students.

In the preceding valid syllogism, both the major premise and the minor premise are factual statements. If both these premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true. Because the syllogism is both valid and true, it is also sound.

However, a syllogism can be valid without being true. For example, look at the following syllogism:

MAJOR PREMISE

All recipients of support services are wealthy.

MINOR PREMISE

Dillon is a recipient of support services.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, Dillon is wealthy.

As illogical as it may seem, this syllogism is valid: its conclusion follows logically from its premises. The major premise states that recipients of support services—all such recipients—are wealthy. However, this premise is clearly false: some recipients of support services may be wealthy, but more are probably not. For this reason, even though the syllogism is valid, it is not true.

Keep in mind that validity is a test of an argument’s structure, not of its soundness. Even if a syllogism’s major and minor premises are true, its conclusion may not necessarily be valid.

Consider the following examples of invalid syllogisms.

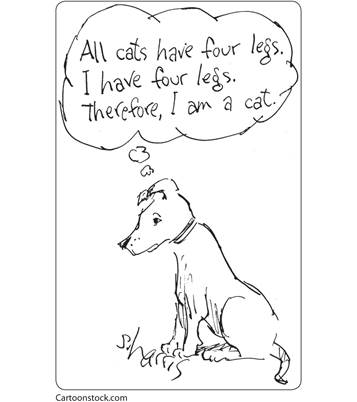

Syllogism with an Illogical Middle Term

A syllogism with an illogical middle term cannot be valid. The middle term of a syllogism is the term that occurs in both the major and minor premises but not in the conclusion. (It links the major term and the minor term together in the syllogism.) A middle term of a valid syllogism must refer to all members of the designated class or group—for example, all dogs, all people, all men, or all women.

Consider the following invalid syllogism:

MAJOR PREMISE

All dogs are mammals.

MINOR PREMISE

Some mammals are porpoises.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, some porpoises are dogs.

Even though the statements in the major and minor premises are true, the syllogism is not valid. Mammals is the middle term because it appears in both the major and minor premises. However, because the middle term mammal does not refer to all mammals, it cannot logically lead to a valid conclusion.

The cartoon shows a dog. The thought bubble of the dog reads, All cats have four legs. I have four legs. Therefore, I am a cat.

In the syllogism that follows, the middle term does refer to all members of the designated group, so the syllogism is valid:

MAJOR PREMISE

All dogs are mammals.

MINOR PREMISE

Ralph is a dog.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, Ralph is a mammal.

Syllogism with a Key Term Whose Meaning Shifts

A syllogism that contains a key term whose meaning shifts cannot be valid. For this reason, the meaning of a key term must remain consistent throughout the syllogism.

Consider the following invalid syllogism:

MAJOR PREMISE

Only man is capable of analytical reasoning.

MINOR PREMISE

Anna is not a man.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, Anna is not capable of analytical reasoning.

In the major premise, man refers to mankind—that is, to all human beings. In the minor premise, however, man refers to males. In the following valid syllogism, the key terms remain consistent:

MAJOR PREMISE

All educated human beings are capable of analytical reasoning.

MINOR PREMISE

Anna is an educated human being.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, Anna is capable of analytical reasoning.

Syllogism with Negative Premise

If either premise in a syllogism is negative, then the conclusion must also be negative.

The following syllogism is not valid:

MAJOR PREMISE

Only senators can vote on legislation.

MINOR PREMISE

No students are senators.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, students can vote on legislation.

Because one of the premises of the syllogism above is negative (“No students are senators”), the only possible valid conclusion must also be negative (“Therefore, no students can vote on legislation”).

If both premises are negative, however, the syllogism cannot have a valid conclusion:

MAJOR PREMISE

Disabled students may not be denied special help.

MINOR PREMISE

Jen is not a disabled student.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, Jen may not be denied special help.

In the preceding syllogism, both premises are negative. For this reason, the syllogism cannot have a valid conclusion. (How can Jen deserve special help if she is not a disabled student?) To have a valid conclusion, this syllogism must have only one negative premise:

MAJOR PREMISE

Disabled students may not be denied special help.

MINOR PREMISE

Jen is a disabled student.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, Jen may not be denied special help.

Recognizing Enthymemes

An enthymeme is a syllogism with one or two parts of its argument—usually, the major premise—missing. In everyday life, we often leave out parts of arguments—most of the time because we think they are so obvious (or clearly implied) that they don’t need to be stated. We assume that the people hearing or reading the arguments will easily be able to fill in the missing parts.

Many enthymemes are presented as a reason plus a conclusion. Consider the following enthymeme:

Enrique has lied, so he cannot be trusted.

In the preceding statement, the minor premise (the reason) and the conclusion are stated, but the major premise is only implied. Once the missing term has been supplied, the logical structure of the enthymeme becomes clear:

MAJOR PREMISE

People who lie cannot be trusted.

MINOR PREMISE

Enrique has lied.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, Enrique cannot be trusted.

It is important to identify enthymemes in arguments you read because some writers, knowing that readers often accept enthymemes uncritically, use them intentionally to unfairly influence readers.

Consider this enthymeme:

Because Liz receives a tuition grant, she should work.

Although some readers might challenge this statement, others will accept it uncritically. When you supply the missing premise, however, the underlying assumptions of the enthymeme become clear—and open to question:

MAJOR PREMISE

All students who receive tuition grants should work.

MINOR PREMISE

Liz receives a tuition grant.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, Liz should work.

Perhaps some people who receive tuition grants should work, but should everyone? What about those who are ill or who have disabilities? What about those who participate in varsity sports or have unpaid internships? The enthymeme oversimplifies the issue and should not be accepted at face value.

At first glance, the following enthymeme might seem to make sense:

North Korea is ruled by a dictator, so it should be invaded.

However, consider the same enthymeme with the missing term supplied:

MAJOR PREMISE

All countries governed by dictators should be invaded.

MINOR PREMISE

North Korea is a country governed by a dictator.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, North Korea should be invaded.

Once the missing major premise has been supplied, the flaws in the argument become clear. Should all nations governed by dictators be invaded? Who should do the invading? Who would make this decision? What would be the consequences of such a policy? As this enthymeme illustrates, if the major premise of a deductive argument is questionable, then the rest of the argument will also be flawed.

BUMPER-STICKER THINKING

Bumper stickers often take the form of enthymemes:

§ Self-control beats birth control.

§ Peace is patriotic.

§ A woman’s place is in the House … and in the Senate.

§ Ban cruel traps.

§ Evolution is a theory—kind of like gravity.

§ I work and pay taxes so wealthy people don’t have to.

§ The Bible says it, I believe it, that settles it.

§ No one needs a mink coat except a mink.

§ Celebrate diversity.

Most often, bumper stickers state just the conclusion of an argument and omit both the major and minor premises. Careful readers, however, will supply the missing premises and thus determine whether the argument is sound.

Bumper stickers on a car.

![]()

EXERCISE 5.1 CONSTRUCTING A SYLLOGISM

Read the following paragraph. Then, restate its main argument as a syllogism.

Drunk Driving Should Be Legalized

In ordering states to enforce tougher drunk driving standards by making it a crime to drive with a blood-alcohol concentration of .08 percent or higher, government has been permitted to criminalize the content of drivers’ blood instead of their actions. The assumption that a driver who has been drinking automatically presents a danger to society even when no harm has been caused is a blatant violation of civil liberties. Government should not be concerned with the probability and propensity of a drinking driver to cause an accident; rather, laws should deal only with actions that damage person or property. Until they actually commit a crime, drunk drivers should be liberated from the force of the law. (From “Legalize Drunk Driving,” by Llewellyn H. Rockwell Jr., WorldNetDaily.com)

![]()

EXERCISE 5.2 ANALYZING DEDUCTIVE LOGIC

Read the following paragraphs. Then, answer the questions that follow.

Animals Are Equal to Humans

According to the United Nations, a person may not be killed, exploited, cruelly treated, intimidated, or imprisoned for no good reason. Put another way, people should be able to live in peace, according to their own needs and preferences.

Who should have these rights? Do they apply to people of all races? Children? People who are brain damaged or senile? The declaration makes it clear that basic rights apply to everyone. To make a slave of someone who is intellectually handicapped or of a different race is no more justifiable than to make a slave of anyone else.

The reason why these rights apply to everyone is simple: regardless of our differences, we all experience a life with its mosaic of thoughts and feelings. This applies equally to the princess and the hobo, the brain surgeon and the dunce. Our value as individuals arises from this capacity to experience life, not because of any intelligence or usefulness to others. Every person has an inherent value, and deserves to be treated with respect in order to make the most of their unique life experience. (Excerpted from “Human and Animal Rights,” by AnimalLiberation.org)

1. What unstated assumptions about the subject does the writer make? Does the writer expect readers to accept these assumptions? How can you tell?

2. What kind of supporting evidence does the writer provide?

3. What is the major premise of this argument?

4. Express the argument that is presented in these paragraphs as a syllogism.

5. Evaluate the syllogism you constructed. Is it true? Is it valid? Is it sound?

![]()

EXERCISE 5.3 JUDGING THE SOUNDNESS OF A DEDUCTIVE ARGUMENT

Read the following five arguments, and determine whether each is sound. (To help you evaluate the arguments, you may want to try arranging them as syllogisms.)

1. All humans are mortal. Ahmed is human. Therefore, Ahmed is mortal.

2. Perry should order eggs or oatmeal for breakfast. She won’t order eggs, so she should order oatmeal.

3. The cafeteria does not serve meat loaf on Friday. Today is not Friday. Therefore, the cafeteria will not serve meat loaf.

4. All reptiles are cold-blooded. Geckos are reptiles. Therefore, geckos are cold-blooded.

5. All triangles have three equal sides. The figure on the board is a triangle. Therefore, it must have three equal sides.

![]()

EXERCISE 5.4 ANALYZING ENTHYMEMES

Read the following ten enthymemes, which come from bumper stickers. Supply the missing premises, and then evaluate the logic of each argument.

1. If you love your pet, don’t eat meat.

2. War is terrorism.

3. Real men don’t ask for directions.

4. Immigration is the sincerest form of flattery.

5. I eat local because I can.

6. Vote nobody for president 2020.

7. I read banned books.

8. Love is the only solution.

9. It’s a child, not a choice.

10. Buy American.

Writing Deductive Arguments

Deductive arguments begin with a general principle and reach a specific conclusion. They develop that principle with logical arguments that are supported by evidence—facts, observations, the opinions of experts, and so on. Keep in mind that no single structure is suitable for all deductive (or inductive) arguments. Different issues and different audiences will determine how you arrange your ideas.

In general, deductive essays can be structured in the following way:

INTRODUCTION

Presents an overview of the issue

States the thesis

BODY

Presents evidence: point 1 in support of the thesis

Presents evidence: point 2 in support of the thesis

Presents evidence: point 3 in support of the thesis

Refutes the arguments against the thesis

CONCLUSION

Brings argument to a close

Concluding statement reinforces the thesis

![]()

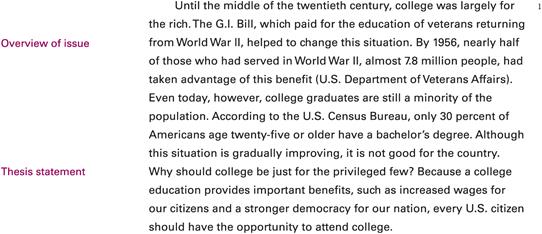

EXERCISE 5.5 IDENTIFYING THE ELEMENTS OF A DEDUCTIVE ARGUMENT

The following student essay, “College Should Be for Everyone,” includes all the elements of a deductive argument. The student who wrote this essay was responding to the question, “Should everyone be encouraged to go to college?” After you read the essay, answer the questions on pages 138—141, consulting the outline above if necessary.

COLLEGE SHOULD BE FOR EVERYONE

CRYSTAL SANCHEZ

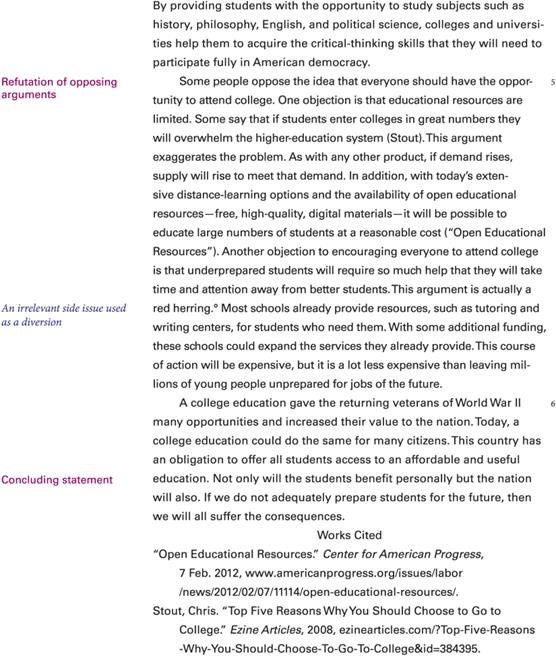

Text reads as follows:

First paragraph: Until the middle of the twentieth century, college was largely for the rich. The G.I. Bill, which paid for the education of veterans returning from World War II, helped to change this situation (a corresponding margin note reads, Overview of issue). By 1956, nearly half of those who had served in World War II, almost 7.8 million people, had taken advantage of this benefit (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs). Even today, however, college graduates are still a minority of the popuLATion. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, only 30 percent of

Americans age twenty-five or older have a bachelor’s degree. Although this situation is gradually improving, it is not good for the country. Why should college be just for the privileged few? (A corresponding margin note reads, Thesis statement) Because a college education provides important benefits, such as increased wages for our citizens and a stronger democracy for our nation, every U.S. citizen should have the opportunity to attend college.

Text continues as follows:

Second paragraph: One reason everyone should have the opportunity to go to college is that a college education gives people a chance to discover what they are good at (a corresponding margin note reads, Evidence: Point 1). It is hard for people to know if they are interested in statistics or public policy or marketing unless they have the chance to explore these subjects. College—and only college—can give them this opportunity. Where else can a person be exposed to a large number of courses taught by experts in a variety of disciplines? Such exposure can open new areas of interest and lead to a much wider set of career options— and thus to a better life (Stout). Without college, most people have limited options and never realize their true potential. Although life and work experiences can teach a person a lot of things, the best education is the broad kind that college offers.

Third paragraph: Another reason everyone should have the opportunity to go to college is that more and more jobs are being phased out or moved overseas (a corresponding margin note reads, Evidence: Point 2). Americans should go to college to develop the skills that they will need to get the best jobs that will remain in the United States. Over the last few decades, midlevel jobs have been steadily disappearing. If this trend continues, the American workforce will be divided in two. One part will consist of low-wage, low-skill service jobs, such as those in food preparation and retail sales, and the other part will be high-skill, high-wage jobs, such as those in management and professional fields like business and engineering. According to a recent report, to compete in the future job market, Americans will need the skills that colleges teach. Future workers will need to be problem solvers who can think both critically and creatively and who can adapt to new situations. They will also need a global awareness, knowledge of many cultures and disciplines, and the ability to communicate in different forms of media. To master these skills, Americans have to be college educated (“Ten Skills for the Future Workforce”).

Fourth paragraph: Perhaps the best reason everyone should have the opportunity to go to college is that education is an essential component of a democratic society (a corresponding margin note reads, Evidence: Point 3). Those without the ability to understand and analyze news reports are not capable of contributing to the social, political, and economic growth of the country. Democracy requires informed citizens who will be able to analyze complicated issues in areas such as finance, education, and public health; weigh competing claims of those running for public office; and assess the job performance of elected officials.

Fourth paragraph continues as follows:

By providing students with the opportunity to study subjects such as history, philosophy, English, and political science, colleges and universities help them to acquire the critical-thinking skills that they will need to participate fully in American democracy.

Fifth paragraph: Some people oppose the idea that everyone should have the opportunity to attend college (a corresponding margin note reads, Refutation of opposing 5 arguments). One objection is that educational resources are limited. Some say that if students enter colleges in great numbers they will overwhelm the higher-education system (Stout). This argument exaggerates the problem. As with any other product, if demand rises, supply will rise to meet that demand. In addition, with today’s extensive distance-learning options and the availability of open educational resources—free, high-quality, digital materials—it will be possible to educate large numbers of students at a reasonable cost (“Open Educational Resources”). Another objection to encouraging everyone to attend college is that underprepared students will require so much help that they will take time and attention away frombetter students. This argument is actually a red herring (a corresponding margin note reads, An irrelevant side issue used as a diversion). Most schools already provide resources, such as tutoring and writing centers, for students who need them. With some additional funding, these schools could expand the services they already provide. This course of action will be expensive, but it is a lot less expensive than leaving millions of young people unprepared for jobs of the future.

Sixth paragraph: A college education gave the returning veterans of World War II many opportunities and increased their value to the nation. Today, a college education could do the same for many citizens. This country has an obligation to offer all students access to an affordable and useful education. Not only will the students benefit personally but the nation will also (a corresponding margin note reads, Concluding statement). If we do not adequately prepare students for the future, then we will all suffer the consequences.

Works Cited

“Open Educational Resources.”Center for American Progress, 7 Feb. 2012, www.americanprogress.org/issues/labor/news/2012/02/07/11114/open-educational-resources/.

Stout, Chris. “Top Five Reasons Why You Should Choose to Go to College.” Ezine Articles, 2008, ezinearticles.com/?Top-Five-Reasons-Why-You-Should-Choose-To-Go-To-College&id=384395.

“Ten Skills for the Future Workforce.” The Atlantic, 22 June 2011, www .theatlantic.com/education/archive/2011/06/ten-skills-for-future-work /473484/.

United States Census Bureau. “Highest Educational Levels Reached by Adults in the U.S. Since 1940.” US Census Bureau Newsroom, 23 Feb. 2017, www.census.gov/press-releases/2017/cb17-51.html.

---, Department of Veterans Affairs. “Born of Controversy: The GI Bill of Rights.” GI Bill History, 20 Oct. 2008, www.va.gov/opa/publications /celebrate/gi-bill.pdf.

Identifying the Elements of a Deductive Argument

1. Paraphrase this essay’s thesis.

2. What arguments does the writer present as evidence to support her thesis? Which do you think is the strongest argument? Which is the weakest?

3. What opposing arguments does the writer address? What other opposing arguments could she have addressed?

4. What points does the conclusion emphasize? Do you think that any other points should be emphasized?

5. Construct a syllogism that expresses the essay’s argument. Then, check your syllogism to make sure it is sound.

What Is Inductive Reasoning?

Inductive reasoning begins with specific observations (or evidence) and goes on to draw a general conclusion. You can see how induction works by looking at the following list of observations:

§ Nearly 80 percent of ocean pollution comes from runoff.

§ Runoff pollution can make ocean water unsafe for fish and people.

§ In some areas, runoff pollution has forced beaches to be closed.

§ Drinking water can be contaminated by runoff.

§ More than one-third of shellfish growing in waters in the United States are contaminated by runoff.

§ Each year, millions of dollars are spent to restore polluted areas.

§ There is a causal relationship between agricultural runoff and water-borne organisms that damage fish.

After studying these observations, you can use inductive reasoning to reach the conclusion that runoff pollution (rainwater that becomes polluted after it comes in contact with earth-bound pollutants such as fertilizer, pet waste, sewage, and pesticides) is a problem that must be addressed.

Children learn about the world by using inductive reasoning. For example, very young children see that if they push a light switch up, the lights in a room go on. If they repeat this action over and over, they reach the conclusion that every time they push a switch, the lights will go on. Of course, this conclusion does not always follow. For example, the lightbulb may be burned out or the switch may be damaged. Even so, their conclusion usually holds true. Children also use induction to generalize about what is safe and what is dangerous. If every time they meet a dog, the encounter is pleasant, they begin to think that all dogs are friendly. If at some point, however, a dog snaps at them, they question the strength of their conclusion and modify their behavior accordingly.

Scientists also use induction. In 1620, Sir Francis Bacon first proposed the scientific method—a way of using induction to find answers to questions. When using the scientific method, a researcher proposes a hypothesis and then makes a series of observations to test this hypothesis. Based on these observations, the researcher arrives at a conclusion that confirms, modifies, or disproves the hypothesis.

REACHING INDUCTIVE CONCLUSIONS

Here are some of the ways you can use inductive reasoning to reach conclusions:

§ Particular to general: This form of induction occurs when you reach a general conclusion based on particular pieces of evidence. For example, suppose you walk into a bathroom and see that the mirrors are fogged. You also notice that the bathtub has drops of water on its sides and that the bathroom floor is wet. In addition, you see a damp towel draped over the sink. Putting all these observations together, you conclude that someone has recently taken a bath. (Detectives use induction when gathering clues to solve a crime.)

§ General to general: This form of induction occurs when you draw a conclusion based on the consistency of your observations. For example, if you determine that Apple Inc. has made good products for a long time, you conclude it will continue to make good products.

§ General to particular: This form of induction occurs when you draw a conclusion based on what you generally know to be true. For example, if you believe that cars made by the Ford Motor Company are reliable, then you conclude that a Ford Focus will be a reliable car.

§ Particular to particular: This form of induction occurs when you assume that because something works in one situation, it will also work in another similar situation. For example, if Krazy Glue fixed the broken handle of one cup, then you conclude it will probably fix the broken handle of another cup.

Making Inferences

Unlike deduction, which reaches a conclusion based on information provided by the major and minor premises, induction uses what you know to make a statement about something that you don’t know. While deductive arguments can be judged in absolute terms (they are either valid or invalid), inductive arguments are judged in relative terms (they are either strong or weak).

You reach an inductive conclusion by making an inference—a statement about what is unknown based on what is known. (In other words, you look at the evidence and try to figure out what is going on.) For this reason, there is always a gap between your observations and your conclusion. To bridge this gap, you have to make an inductive leap—a stretch of the imagination that enables you to draw an acceptable conclusion. Therefore, inductive conclusions are never certain (as deductive conclusions are) but only probable. The more evidence you provide, the stronger and more probable are your conclusions (and your argument).

Public-opinion polls illustrate how inferences are used to reach inductive conclusions. Politicians and news organizations routinely use public-opinion polls to assess support (or lack of support) for a particular policy, proposal, or political candidate. After surveying a sample population—registered voters, for example—pollsters reach conclusions based on their responses. In other words, by asking questions and studying the responses of a sample group of people, pollsters make inferences about the larger group—for example, which political candidate is ahead and by how much. How solid these inferences are depends to a great extent on the sample populations the pollsters survey. In an election, for example, a poll of randomly chosen individuals will be less accurate than a poll of registered voters or likely voters. In addition, other factors (such as the size of the sample and the way questions are worded) can determine the relative strength of an inductive conclusion.

As with all inferences, a gap exists between a poll’s data—the responses to the questions—and the conclusion. The larger and more representative the sample, the smaller the inductive leap necessary to reach a conclusion and the more accurate the poll. If the gap between the data and the conclusion is too big, however, the pollsters will be accused of making a hasty generalization (see p. 154). Remember, no matter how much support you present, an inductive conclusion is only probable, never certain. The best you can do is present a convincing case and hope that your audience will accept it.

Constructing Strong Inductive Arguments

When you use inductive reasoning, your conclusion is only as strong as the evidence—the facts, details, or examples—that you use to support it. For this reason, you should be on the lookout for the following problems that can occur when you try to reach an inductive conclusion.

Generalization Too Broad

The conclusion you state cannot go beyond the scope of your evidence. Your evidence must support your generalization. For instance, you cannot survey just three international students in your school and conclude that the school does not go far enough to accommodate international students. To reach such a conclusion, you would have to consider a large number of international students.

Atypical Evidence

The evidence on which you base an inductive conclusion must be representative, not atypical or biased. For example, you cannot conclude that students are satisfied with the course offerings at your school by sampling just first-year students. To be valid, your conclusion should be based on responses from a cross section of students from all years.

Irrelevant Evidence

Your evidence has to support your conclusion. If it does not, it is irrelevant. For example, if you assert that many adjunct faculty members make substantial contributions to your school, your supporting examples must be adjunct faculty, not tenured or junior faculty.

Exceptions to the Rule

There is always a chance that you will overlook an exception that may affect the strength of your conclusion. For example, not everyone who has a disability needs special accommodations, and not everyone who requires special accommodations needs the same services. For this reason, you should avoid using words like every, all, and always and instead use words like most, many, and usually.

![]()

EXERCISE 5.6 IDENTIFYING DEDUCTIVE AND INDUCTIVE ARGUMENTS

Read the following arguments, and decide whether each is a deductive argument or an inductive argument and write D or I on the lines.

1. Freedom of speech is a central principle of our form of government. For this reason, students should be allowed to wear T-shirts that call for the legalization of marijuana.

2. The Chevy Cruze Eco gets twenty-seven miles a gallon in the city and forty-six miles a gallon on the highway. The Honda Accord gets twenty-seven miles a gallon in the city and thirty-six miles a gallon on the highway. Therefore, it makes more sense for me to buy the Chevy Cruze Eco.

3. In Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “The Cask of Amontillado,” Montresor flatters Fortunato. He lures him to his vaults where he stores wine. Montresor then gets Fortunato drunk and chains him to the wall of a crypt. Finally, Montresor uncovers a pile of building material and walls up the entrance to the crypt. Clearly, Montresor has carefully planned to murder Fortunato for a very long time.

4. All people should have the right to die with dignity. Garrett is a terminally ill patient, so he should have access to doctor-assisted suicide.

5. Last week, we found unacceptably high levels of pollution in the ocean. On Monday, we also found high levels of pollution. Today, we found even higher levels of pollution. We should close the ocean beaches to swimmers until we can find the source of this problem.

![]()

EXERCISE 5.7 ANALYZING DEDUCTIVE AND INDUCTIVE ARGUMENTS

Read the following arguments. Then, decide whether they are deductive or inductive. If they are inductive arguments, evaluate their strength. If they are deductive arguments, evaluate their soundness.

1. The Farmer’s Almanac says that this winter will be very cold. The National Weather Service also predicts that this winter will be very cold. So, this should be a cold winter.

2. Many walled towns in Europe do not let people drive cars into their centers. San Gimignano is a walled town in Europe. It is likely that we will not be able to drive our car into its center.

3. The window at the back of the house is broken. There is a baseball on the floor. A few minutes ago, I saw two boys playing catch in a neighbor’s yard. They must have thrown the ball through the window.

4. Every time I go to the beach I get sunburned. I guess I should stop going to the beach.

5. All my instructors have advanced degrees. Richard Bell is one of my instructors. Therefore, Richard Bell has an advanced degree.

6. My last two boyfriends cheated on me. All men are terrible.

7. I read a study published by a pharmaceutical company that said that Accutane was safe. Maybe the government was too quick to pull this drug off the market.

8. Chase is not very good-looking, and he dresses badly. I don’t know how he can be a good architect.

9. No fictional character has ever had a fan club. Harry Potter does, but he is the exception.

10. Two weeks ago, my instructor refused to accept a late paper. She did the same thing last week. Yesterday, she also told someone that because his paper was late, she wouldn’t accept it. I’d better get my paper in on time.

![]()

EXERCISE 5.8 ANALYZING AN INDUCTIVE PARAGRAPH

Read the following inductive paragraph, written by student Pooja Vaidya, and answer the questions that follow it.

When my friend took me to a game between the Philadelphia Eagles and the Dallas Cowboys in Philadelphia, I learned a little bit about American football and a lot about the behavior of football fans. Many of the Philadelphia fans were dressed in green and white football jerseys, each with a player’s name and number on the back. One fan had his face painted green and wore a green cape with a large white E on it. He ran up and down the aisles in his section and led cheers. When the team was ahead, everyone joined in. When the team fell behind, this fan literally fell on his knees, cried, and begged the people in the stands to support the Eagles. (After the game, several people asked him for his autograph.) A group of six fans sat without shirts. They wore green wigs, and each had one letter of the team’s name painted on his bare chest. Even though the temperature was below freezing, none of these fans ever put on his shirt. Before the game, many fans had been drinking at tailgate parties in the parking lot, and as the game progressed, they continued to drink beer in the stadium. By the beginning of the second half, fights were breaking out all over the stadium. Guards grabbed the people who were fighting and escorted them out of the stadium. At one point, a fan wearing a Dallas jersey tried to sit down in the row behind me. Some of the Eagles fans were so threatening that the police had to escort the Dallas fan out of the stands for his own protection. When the game ended in an Eagles victory, the fans sang the team’s fight song as they left the stadium. I concluded that for many Eagles fans, a day at the stadium is an opportunity to engage in behavior that in any other context would be unacceptable and even abnormal.

1. Which of the following statements could you not conclude from this paragraph?

a. All Eagles fans act in outrageous ways at games.

b. At football games, the fans in the stands can be as violent as the players on the field.

c. The atmosphere at the stadium causes otherwise normal people to act abnormally.

d. Spectator sports encourage fans to act in abnormal ways.

e. Some people get so caught up in the excitement of a game that they act in uncharacteristic ways.

2. Paraphrase the writer’s conclusion. What evidence is provided to support this conclusion?

3. What additional evidence could the writer have provided? Is this additional evidence necessary, or does the conclusion stand without it?

4. The writer makes an inductive leap to reach the paragraph’s conclusion. Do you think this leap is too great?

5. Does this paragraph make a strong inductive argument? Why or why not?

Writing Inductive Arguments

Inductive arguments begin with evidence (specific facts, observations, expert opinion, and so on), draw inferences from the evidence, and reach a conclusion by making an inductive leap. Keep in mind that inductive arguments are only as strong as the link between the evidence and the conclusion, so the stronger this link is, the stronger the argument will be.

Inductive essays frequently have the following structure:

INTRODUCTION

Presents the issue

States the thesis

BODY

Presents evidence: facts, observations, expert opinion, and so on

Draws inferences from the evidence

Refutes the arguments against the thesis

CONCLUSION

Brings argument to a close

Concluding statement reinforces the thesis

![]()

EXERCISE 5.9 IDENTIFYING THE ELEMENTS OF AN INDUCTIVE ESSAY

The following essay includes all the elements of an inductive argument. After you read the essay, answer the questions on page 151, consulting the preceding outline if necessary.

PLEASE DO NOT FEED THE HUMANS

WILLIAM SALETAN

This essay appeared in Slate on September 2, 2006.

In 1894, Congress established Labor Day to honor those who “from rude nature have delvedi and carved all the grandeur we behold.” In the century since, the grandeur of human achievement has multiplied. Over the past four decades, global population has doubled, but food output, driven by increases in productivity, has outpaced it. Poverty, infant mortality, and hunger are receding. For the first time in our planet’s history, a species no longer lives at the mercy of scarcity. We have learned to feed ourselves.

We’ve learned so well, in fact, that we’re getting fat. Not just the United States or Europe, but the whole world. Egyptian, Mexican, and South African women are now as fat as Americans. Far more Filipino adults are now overweight than underweight. In China, one in five adults is too heavy, and the rate of overweight children is 28 times higher than it was two decades ago. In Thailand, Kuwait, and Tunisia, obesity, diabetes, and heart disease are soaring.

Hunger is far from conquered. But since 1990, the global rate of malnutrition has declined an average of 1.7 percent a year. Based on data from the World Health Organization and the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization, for every two people who are malnourished, three are now overweight or obese. Among women, even in most African countries, overweight has surpassed underweight. The balance of peril is shifting.

Fat is no longer a rich man’s disease. For middle- and high-income Americans, the obesity rate is 29 percent. For low-income Americans, it’s 35 percent. Among middle- and high-income kids aged 15 to 17, the rate of overweight is 14 percent. Among low-income kids in the same age bracket, it’s 23 percent. Globally, weight has tended to rise with income. But a study in Vancouver, Canada, published three months ago, found that preschoolers in “food-insecure” households were twice as likely as other kids to be overweight or obese. In Brazilian cities, the poor have become fatter than the rich.

Technologically, this is a triumph. In the early days of our species, even the rich starved. Barry Popkin, a nutritional epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina, divides history into several epochs. In the hunter-gatherer era, if we didn’t find food, we died. In the agricultural era, if our crops perished, we died. In the industrial era, famine receded, but infectious diseases killed us. Now we’ve achieved such control over nature that we’re dying not of starvation or infection, but of abundance. Nature isn’t killing us. We’re killing ourselves.

You don’t have to go hungry anymore; we can fill you with fats and carbs more cheaply than ever. You don’t have to chase your food; we can bring it to you. You don’t have to cook it; we can deliver it ready-to-eat. You don’t have to eat it before it spoils; we can pump it full of preservatives so it lasts forever. You don’t even have to stop when you’re full. We’ve got so much food to sell, we want you to keep eating.

What happened in America is happening everywhere, only faster. Fewer farmers’ markets, more processed food. Fewer whole grains, more refined ones. More sweeteners, salt, and trans fats. Cheaper meat, more animal fat. Less cooking, more eating out. Bigger portions, more snacks.

Kentucky Fried Chicken and Pizza Hut are spreading across the planet. Coca-Cola is in more than 200 countries. Half of McDonald’s business is overseas. In China, animal-fat intake has tripled in 20 years. By 2020, meat consumption in developing countries will grow by 106 million metric tons, outstripping growth in developed countries by a factor of more than five. Forty years ago, to afford a high-fat diet, your country needed a gross national product per capita of nearly $1,500. Now the price is half that. You no longer have to be rich to die a rich man’s death.

Soon, it’ll be a poor man’s death. The rich have Whole Foods, gyms, and personal trainers. The poor have 7-Eleven, Popeyes, and streets unsafe for walking. When money’s tight, you feed your kids at Wendy’s and stock up on macaroni and cheese. At a lunch buffet, you do what your ancestors did: store all the fat you can.

That’s the punch line: Technology has changed everything but us. We evolved to survive scarcity. We crave fat. We’re quick to gain weight and slow to lose it. Double what you serve us, and we’ll double what we eat. Thanks to technology, the deprivation that made these traits useful is gone. So is the link between flavors and nutrients. The modern food industry can sell you sweetness without fruit, salt without protein, creaminess without milk. We can fatten you and starve you at the same time.

“We evolved to survive scarcity.”

And that’s just the diet side of the equation. Before technology, adult men had to expend about 3,000 calories a day. Now they expend about 2,000. Look at the new Segway scooter. The original model relieved you of the need to walk, pedal, or balance. With the new one, you don’t even have to turn the handlebars or start it manually. In theory, Segway is replacing the car. In practice, it’s replacing the body.

In country after country, service jobs are replacing hard labor. The folks who field your customer service calls in Bangalore are sitting at desks. Nearly everyone in China has a television set. Remember when Chinese rode bikes? In the past six years, the number of cars there has grown from six million to 20 million. More than one in seven Chinese has a motorized vehicle, and households with such vehicles have an obesity rate 80 percent higher than their peers.

The answer to these trends is simple. We have to exercise more and change the food we eat, donate, and subsidize. Next year, for example, the U.S. Women, Infants, and Children program, which subsidizes groceries for impoverished youngsters, will begin to pay for fruits and vegetables. For 32 years, the program has fed toddlers eggs and cheese but not one vegetable. And we wonder why poor kids are fat.

The hard part is changing our mentality. We have a distorted body image. We’re so used to not having enough, as a species, that we can’t believe the problem is too much. From China to Africa to Latin America, people are trying to fatten their kids. I just got back from a vacation with my Jewish mother and Jewish mother-in-law. They told me I need to eat more.

The other thing blinding us is liberal guilt. We’re so caught up in the idea of giving that we can’t see the importance of changing behavior rather than filling bellies. We know better than to feed buttered popcorn to zoo animals, yet we send it to a food bank and call ourselves humanitarians. Maybe we should ask what our fellow humans actually need.

Identifying the Elements of an Inductive Argument

1. What is this essay’s thesis? Restate it in your own words.

2. Why do you think Saletan places the thesis where he does?

3. What evidence does Saletan use to support his conclusion?

4. What inductive leap does Saletan make to reach his conclusion? Do you think he should have included more evidence?

5. Overall, do you think Saletan’s inductive argument is relatively strong or weak? Explain.

i Dug

Recognizing Logical Fallacies

When you write arguments in college, you follow certain rules that ensure fairness. Not everyone who writes arguments is fair or thorough, however. Sometimes you will encounter arguments in which writers attack the opposition’s intelligence or patriotism and base their arguments on questionable (or even false) assumptions. As convincing as these arguments can sometimes seem, they are not valid because they contain fallacies—errors in reasoning that undermine the logic of an argument. Familiarizing yourself with the most common logical fallacies can help you to evaluate the arguments of others and to construct better, more effective arguments of your own.

The following pages define and illustrate some logical fallacies that you should learn to recognize and avoid.

Begging the Question

The fallacy of begging the question assumes that a statement is self-evident (or obvious) when it actually requires proof. A conclusion based on such assumptions cannot be valid. For example, someone who is very religious could structure an argument the following way:

MAJOR PREMISE

Everything in the Bible is true.

MINOR PREMISE

The Bible says that Noah built an ark.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, Noah’s ark really existed.

A person can accept the conclusion of this syllogism only if he or she accepts the major premise as self-evident. Some people might find this line of reasoning convincing, but others would not—even if they were religious.

Begging the question occurs any time someone presents a debatable statement as if it were true. For example, look at the following statement:

You have unfairly limited my right of free speech by refusing to print my editorial in the college newspaper.

This statement begs the question because it assumes what it should be proving—that refusing to print an editorial somehow violates a person’s right to free speech.

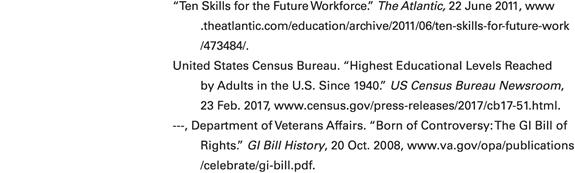

Circular Reasoning

Closely related to begging the question, circular reasoning occurs when someone supports a statement by restating it in different terms. Consider the following statement:

Stealing is wrong because it is illegal.

The conclusion of the preceding statement is essentially the same as its beginning: stealing (which is illegal) is against the law. In other words, the argument goes in a circle.

Here are some other examples of circular reasoning:

§ Lincoln was a great president because he is the best president we ever had.

§ I am for equal rights for women because I am a feminist.

§ Only someone who is deranged would carry out a school shooting, so he must be mentally ill.

All of the preceding statements have one thing in common: they attempt to support a statement by simply repeating the statement in different words.

The illustration shows a watermill with waterwheel and raised bridges for water to continuously run. The water on the raised bridges appears to run upward and then circle down. A margin note reads, Waterfall, by M. C. Escher. The artwork creates the illusion of water flowing uphill and in a circle. Circular reasoning occurs when the conclusion of an argument is the same as one of the premises.

Weak Analogy

An analogy is a comparison between two items (or concepts)—one familiar and one unfamiliar. When you make an analogy, you explain the unfamiliar item by comparing it to the familiar item.

Although analogies can be effective in arguments, they have limitations. For example, a senator who opposed a government bailout of the financial industry in 2008 made the following argument:

This bailout is doomed from the start. It’s like pouring milk into a leaking bucket. As long as you keep pouring milk, the bucket stays full. But when you stop, the milk runs out the hole in the bottom of the bucket. What we’re doing is throwing money into a big bucket and not fixing the hole. We have to find the underlying problems that have caused this part of our economy to get in trouble and pass legislation to solve them.

The problem with using analogies such as this one is that analogies are never perfect. There is always a difference between the two things being compared. The larger this difference, the weaker the analogy—and the weaker the argument that it supports. For example, someone could point out to the senator that the financial industry—and by extension, the whole economy—is much more complex and multifaceted than a leaking bucket.

This weakness highlights another limitation of an argument by analogy. Even though it can be very convincing, an analogy alone is no substitute for evidence. In other words, to analyze the economy, the senator would have to expand his discussion beyond a single analogy (which cannot carry the weight of the entire argument) and provide convincing evidence that the bailout was a mistake form the start.

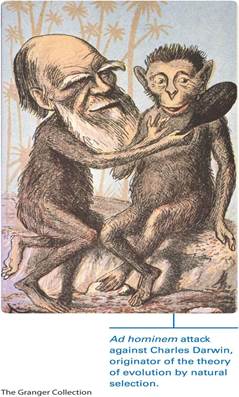

Ad Hominem Fallacy (Personal Attack)

The ad hominem fallacy occurs when someone attacks the character or the motives of a person instead of focusing on the issues. This line of reasoning is illogical because it focuses attention on the person making the argument, sidestepping the argument itself.

Consider the following statement:

Dr. Thomson, I’m not sure why we should believe anything you have to say about this community health center. Last year, you left your husband for another man.

The preceding attack on Dr. Thomson’s character is irrelevant; it has nothing to do with her ideas about the community health center. Sometimes, however, a person’s character may have a direct relation to the issue. For example, if Dr. Thomson had invested in a company that supplied medical equipment to the health center, this fact would have been relevant to the issue at hand.

The ad hominem fallacy also occurs when you attempt to undermine an argument by associating it with individuals who are easily attacked. For example, consider this statement:

I think your plan to provide universal health care is interesting. I’m sure Marx and Lenin would agree with you.

Instead of focusing on the specific provisions of the health-care plan, the opposition unfairly associates it with the ideas of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin, two well-known Communists.

Darwin is shown sitting next to another monkey and holding a mirror up to it. A margin note reads, Ad hominem attack against Charles Darwin, originator of the theory of evolution by natural selection.

Creating a Straw Man

This fallacy most likely got its name from the use of straw dummies in military and boxing training. When writers create a straw man, they present a weak argument that can easily be refuted. Instead of attacking the real issue, they focus on a weaker issue and give the impression that they have effectively countered an opponent’s argument. Frequently, the straw man is an extreme or oversimplified version of the opponent’s actual position. For example, during a debate about raising the minimum wage, a senator made the following comment:

If we raise the minimum wage for restaurant workers, the cost of a meal will increase. Soon, the average person won’t be able to afford a cup of soup.

Instead of focusing on legitimate arguments against the minimum wage, the senator misrepresents an opposing argument and then refutes it. As this example shows, the straw man fallacy is dishonest because it intentionally distorts an opponent’s position in order to mislead readers.

Hasty or Sweeping Generalization (Jumping to a Conclusion)

A hasty or sweeping generalization (also called jumping to a conclusion) occurs when someone reaches a conclusion that is based on too little evidence. Many people commit this fallacy without realizing it. For example, when Richard Nixon was elected president in 1972, film critic Pauline Kael is supposed to have remarked, “How can that be? No one I know voted for Nixon!” The general idea behind this statement is that if Kael’s acquaintances didn’t vote for Nixon, then neither did most other people. This assumption is flawed because it is based on a small sample.

The photo shows a long line of soldiers in uniform holding bayonets in position and leaning forward. Each of them has the bayonet pressed against a straw man suspended by ropes from a bar. A bundle of sticks lies next to each soldier. A margin note reads, Soldiers practicing attacks against straw men.

Sometimes people make hasty generalizations because they strongly favor one point of view over another. At other times, a hasty generalization is simply the result of sloppy thinking. For example, it is easier for a student to say that an instructor is an unusually hard grader than to survey the instructor’s classes to see if this conclusion is warranted (or to consider other reasons for his or her poor performance in a course).

Either/Or Fallacy (False Dilemma)

The either/or fallacy (also called a false dilemma) occurs when a person says that there are just two choices when there are actually more. In many cases, the person committing this fallacy tries to force a conclusion by presenting just two choices, one of which is clearly more desirable than the other. (Parents do this with young children all the time: “Eat your carrots, or go to bed.”)

Politicians frequently engage in this fallacy. For example, according to some politicians, you are either pro-life or pro-choice, pro—gun control or anti—gun control, pro-stem-cell research or anti-stem-cell research. Many people, however, are actually somewhere in the middle, taking a much more nuanced approach to complicated issues.

Consider the following statement:

I can’t believe you voted against the bill to build a wall along the southern border of the United States. Either you’re for protecting our border, or you’re against it.

This statement is an example of the either/or fallacy. The person who voted against the bill might be against building the border wall but not against all immigration restrictions. The person might favor loose restrictions for some people (for example, people fleeing political persecution and migrant workers) and strong restrictions for others (for example, drug smugglers and human traffickers). By limiting the options to just two, the speaker oversimplifies the situation and attempts to force the listener to accept a fallacious argument.

Equivocation

The fallacy of equivocation occurs when a key term has one meaning in one part of an argument and another meaning in another part. (When a term is used unequivocally, it has the same meaning throughout the argument.) Consider the following old joke:

The sign said, “Fine for parking here,” so because it was fine, I parked there.

Obviously, the word fine has two different meanings in this sentence. The first time it is used, it means “money paid as a penalty.” The second time, it means “good” or “satisfactory.”

Most words have more than one meaning, so it is important not to confuse the various meanings. For an argument to work, a key term has to have the same meaning every time it appears in the argument. If the meaning shifts during the course of the argument, then the argument cannot be sound.

Consider the following statement:

This is supposed to be a free country, but nothing worth having is ever free.

In this statement, the meaning of a key term shifts. The first time the word free is used, it means “not under the control of another.” The second time, it means “without charge.”

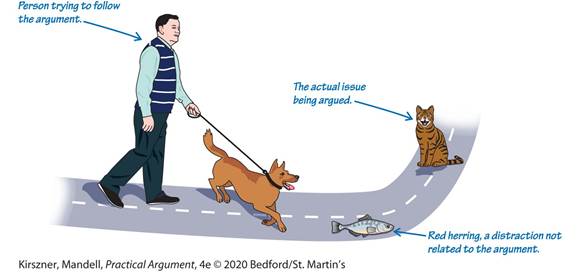

Red Herring

This fallacy gets its name from the practice of dragging a smoked fish across the trail of a fox to mask its scent during a fox hunt. As a result, the hounds lose the scent and are thrown off the track. The red herring fallacy occurs when a person raises an irrelevant side issue to divert attention from the real issue. Used skillfully, this fallacy can distract an audience and change the focus of an argument.

Political campaigns are good sources of examples of the red herring fallacy. Consider this example from the 2016 presidential race:

I know that Donald Trump says that he is for the “little guy,” but he lives in a three-story penthouse in the middle of Manhattan. How can we believe that his policies will help the average American?

The focus of this argument should have been on Trump’s policies, not on the fact that he lives in a penthouse.

Here is another red herring fallacy:

She: I read that the Alexa virtual assistant records your conversations, even when it’s off. This is an invasion of privacy.

He: That certainly is a first-world problem. Think of all the poor people in Haiti. That should put things in perspective.

Again, the focus of the argument should be on a possible invasion of privacy, not on poverty in Haiti.

The illustration shows a man walking along a dotted line, holding a dog by the leash, with the dog leading the man. The label pointing to the man reads, Person trying to follow the argument. The end of the dotted line shows a cat labeled, The actual issue being argued. The dog moves away from the line toward a fish on the other side of the line. The fish is labeled Red herring, a distraction not related to the argument.

Slippery Slope

The slippery-slope fallacy occurs when a person argues that one thing will inevitably result from another. (Other names for the slippery-slope fallacy are the foot-in-the-door fallacy and the floodgates fallacy.) Both these names suggest that once you permit certain acts, you inevitably permit additional acts that eventually lead to disastrous consequences. Typically, the slippery-slope fallacy presents a series of increasingly unacceptable events that lead to an inevitable, unpleasant conclusion. (Usually, there is no evidence that such a sequence will actually occur.)

We encounter examples of the slippery-slope fallacy almost daily. During a debate on same-sex marriage, for example, an opponent advanced this line of reasoning:

If we allow gay marriage, then there is nothing to stop polygamy. And once we allow this, where will it stop? Will we have to legalize incest—or even bestiality?

Whether or not you support same-sex marriage, you should recognize the fallacy of this slippery-slope reasoning. By the last sentence of the preceding passage, the assertions have become so outrageous that they approach parody. People can certainly debate this issue, but not in such a dishonest and highly emotional way.

You Also (Tu Quoque)

The you also fallacy asserts that a statement is false because it is inconsistent with what the speaker has said or done. In other words, a person is attacked for doing what he or she is arguing against. Parents often encounter this fallacy when they argue with their teenage children. By introducing an irrelevant point—“You did it too”—the children attempt to distract parents and put them on the defensive:

§ How can you tell me not to smoke when you used to smoke?

§ Don’t yell at me for drinking. I bet you had a few beers before you were twenty-one.

§ Why do I have to be home by midnight? Didn’t you stay out late when you were my age?

Arguments such as these are irrelevant. People fail to follow their own advice, but that does not mean that their points have no merit. (Of course, not following their own advice does undermine their credibility.)

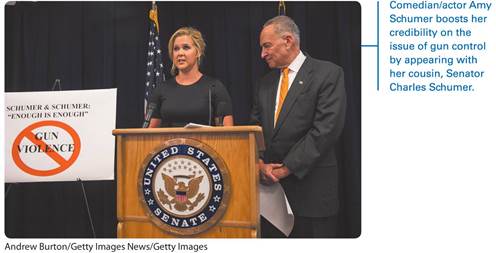

Appeal to Doubtful Authority

Writers of research papers frequently use the ideas of recognized authorities to strengthen their arguments. However, the sources offered as evidence need to be both respected and credible. The appeal to doubtful authority occurs when people use the ideas of nonexperts to support their arguments.

Not everyone who speaks as an expert is actually an authority on a particular issue. For example, when movie stars or recording artists give their opinions about politics, climate change, or foreign affairs—things they may know little about—they are not speaking as experts; therefore, they have no authority. (They are experts, however, when they discuss the film or music industries.) A similar situation occurs with the pundits who appear on television news shows or whose ideas are posted on social media sites. Some of these individuals have solid credentials in the fields they discuss, but others offer opinions even though they know little about the subjects. Unfortunately, many people accept the pronouncements of these “experts” uncritically and think it is acceptable to cite them to support their own arguments.

How do you determine whether a person you read about or hear is really an authority? First, make sure that the person actually has expertise in the field he or she is discussing. You can do this by checking his or her credentials on the internet. Second, make sure that the person is not biased. No one is entirely free from bias, but the bias should not be so extreme that it undermines the person’s authority. Finally, make sure that you can confirm what the so-called expert says or writes. Check one or two pieces of information in other sources, such as a basic reference text or encyclopedia. Determine if others—especially recognized experts in the field—confirm this information. If there are major points of discrepancy, dig further to make sure you are dealing with a legitimate authority. Be extremely wary of material that appears on social media sites, such as Facebook and Twitter, even if it is attributed to experts. Don’t use information until you have checked both its authenticity and accuracy.

A board fixed on a stand to the right of Amy Schumer reads, Schumer and Schumer: Enough is enough. A circle reading Gun violence is crossed out. A margin note reads, Comedian/actor Amy Schumer boosts her credibility on the issue of gun control by appealing with her cousin, Senator Charles Schumer.

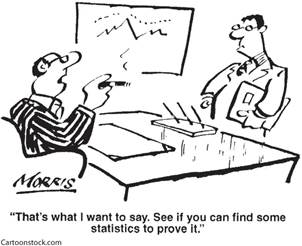

Misuse of Statistics

The misuse of statistics occurs when data are misrepresented. Statistics can be used persuasively in an argument, but sometimes they are distorted—intentionally or unintentionally—to make a point. For example, a classic ad for toothpaste claims that four out of five dentists recommend Crest toothpaste. What the ad neglects to mention is the number of dentists who were questioned. If the company surveyed several thousand dentists, then this statistic would be meaningful. If the company surveyed only ten, however, it would not be.

Misleading statistics can be much subtler (and much more complicated) than the preceding example. For example, one year, there were 16,653 alcohol-related deaths in the United States. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), 12,892 of these 16,653 alcohol-related deaths involved at least one driver or passenger who was legally drunk. Of the 12,892 deaths, 7,326 were the drivers themselves, and 1,594 were legally drunk pedestrians. The remaining 3,972 fatalities were nonintoxicated drivers, passengers, or nonoccupants. These 3,972 fatalities call the total number into question because the NHTSA does not indicate which drivers were at fault. In other words, if a sober driver ran a red light and killed a legally drunk driver, the NHTSA classified this death as alcohol-related. For this reason, the original number of alcohol-related deaths—16,653—is somewhat misleading. (The statistic becomes even more questionable when you consider that a person is automatically classified as intoxicated if he or she refuses to take a sobriety test.)

Post Hoc, Ergo Propter Hoc (After This, Therefore Because of This)

The post hoc fallacy asserts that because two events occur closely in time, one event must cause the other. Professional athletes commit the post hoc fallacy all the time. For example, one major league pitcher wears the same shirt every time he has an important game. Because he has won several big games while wearing this shirt, he believes it brings him luck.

Many events seem to follow a sequential pattern even though they actually do not. For example, some people refuse to get a flu shot because they say that the last time they got one, they came down with the flu. Even though there is no scientific basis for this link, many people insist that it is true. (The more probable explanation for this situation is that the flu vaccination takes at least two weeks to take effect, so it is possible for someone to be infected by the flu virus before the vaccine starts working. In addition, no flu vaccine is 100 percent effective, so even with the shot, it is possible to contract the disease.)

Another health-related issue also illustrates the post hoc fallacy. Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) studied several natural supplements that claim to cure the common cold. Because the study showed that these products were not effective, the FDA ordered the manufacturers to stop making false claims. Despite this fact, however, many people still buy these products. When questioned, they say the medications actually work. Again, the explanation for this phenomenon is simple. Most colds last just a few days. As the FDA pointed out in its report, people who took the medications would have begun feeling better with or without them.

Non Sequitur (It Does Not Follow)

The non sequitur fallacy occurs when a conclusion does not follow from the premises. Frequently, the conclusion is supported by weak or irrelevant evidence—or by no evidence at all. Consider the following statement:

Megan drives an expensive car, so she must be earning a lot of money.

Megan might drive an expensive car, but this is not evidence that she has a high salary. She could, for example, be leasing the car or paying it off over a five-year period, or it could have been a gift.

Non sequiturs are common in political arguments. Consider this statement:

Gangs, drugs, and extreme violence plague today’s prisons. The only way to address this issue is to release all nonviolent offenders as soon as possible.

This assessment of the prison system may be accurate, but it doesn’t follow that because of this situation, all nonviolent offenders should be released immediately.

Scientific arguments also contain non sequiturs. Consider the following statement that was made during a debate on climate change:

Recently, the polar ice caps have thickened, and the temperature of the oceans has stabilized. Obviously, we don’t need to do more to address climate change.

Even if you accept the facts of this argument, you need to see more evidence before you can conclude that no action against climate change is necessary. For example, the cooling trend could be temporary, or other areas of the earth could still be growing warmer.

Bandwagon Fallacy

The bandwagon fallacy occurs when you try to convince people that something is true because it is widely held to be true. It is easy to see the problem with this line of reasoning. Hundreds of years ago, most people believed that the sun revolved around the earth and that the earth was flat. As we know, the fact that many people held these beliefs did not make them true.

The underlying assumption of the bandwagon fallacy is that the more people who believe something, the more likely it is to be true. Without supporting evidence, however, this form of argument cannot be valid. For example, consider the following statement made by a driver who was stopped by the police for speeding:

Officer, I didn’t do anything wrong. Everyone around me was going the same speed.

As the police officer was quick to point out, the driver’s argument missed the point: he was doing fifty-five miles an hour in a thirty-five-mile-an-hour zone, and the fact that other drivers were also speeding was irrelevant. If the driver had been able to demonstrate that the police officer was mistaken—that he was driving more slowly or that the speed limit was actually sixty miles an hour—then his argument would have had merit. In this case, the fact that other drivers were going the same speed would be relevant because it would support his contention.

Since most people want to go along with the crowd, the bandwagon fallacy can be very effective. For this reason, advertisers use it all the time. For example, a book publisher will say that a book has been on the New York Times best-seller list for ten weeks, and a pharmaceutical company will say that its brand of aspirin outsells other brands four to one. These appeals are irrelevant, however, because they don’t address the central questions: Is the book actually worth reading? Is one brand of aspirin really better than other brands?

![]()

EXERCISE 5.10 IDENTIFYING LOGICAL FALLACIES

Determine which of the following statements are logical arguments and which are fallacies. If the statement is not logical, identify the fallacy that best applies.

1. Almost all the students I talked to said that they didn’t like the senator. I’m sure he’ll lose the election on Tuesday.

2. This car has a noisy engine; therefore, it must create a lot of pollution.

3. I don’t know how Professor Resnick can be such a hard grader. He’s always late for class.

4. A vote for the bill to limit gun sales in the city is a vote against the Second Amendment.

5. It’s only fair to pay your fair share of taxes.

6. I had an internship at a government agency last summer, and no one there worked very hard. Government workers are lazy.

7. It’s a clear principle of law that people are not allowed to yell “Fire!” in a crowded theater. By permitting protestors to hold a rally downtown, Judge Cohen is allowing them to do just that.

8. Of course this person is guilty. He wouldn’t be in jail if he weren’t a criminal.

9. Schools are like families; therefore, teachers (like parents) should be allowed to discipline their kids.

10. Everybody knows that staying out in the rain can make you sick.

11. When we had a draft in the 1960s, the crime rate was low. We should bring back the draft.

12. I’m not a doctor, but I play one on TV. I recommend Vicks Formula 44 cough syrup.

13. Some people are complaining about public schools, so there must be a problem.

14. If you aren’t part of the solution, you’re part of the problem.

15. All people are mortal. James is a person. Therefore, James is mortal.

16. I don’t know why you gave me an F for handing in someone else’s essay. Didn’t you ever copy something from someone else?

17. First, the government stops us from buying assault-style rifles. Then, it tries to limit the number of handguns we can buy. What will come next? Soon, they’ll try to take away all our guns.

18. Shakespeare was the world’s greatest playwright; therefore, Macbeth must be a great play.

19. Last month, I bought a new computer. Yesterday, I installed some new software. This morning, my computer wouldn’t start up. The new software must be causing the problem.

20. Ellen DeGeneres and Paul McCartney are against testing pharmaceutical and cosmetics products on animals, and that’s good enough for me.

![]()

EXERCISE 5.11 ANALYZING LOGICAL FALLACIES

Read the following essay, and identify as many logical fallacies in it as you can. Make sure you identify each fallacy by name and are able to explain the flaws in the writer’s arguments.

IMMIGRATION TIME-OUT

PATRICK J. BUCHANAN

This essay is from Buchanan.org, where it appeared on October 31, 1994.

What do we want the America of the years 2000, 2020, and 2050 to be like? Do we have the right to shape the character of the country our grandchildren will live in? Or is that to be decided by whoever, outside America, decides to come here?

By 2050, we are instructed by the chancellor of the University of California at Berkeley, Chang Lin-Tin, “the majority of Americans will trace their roots to Latin America, Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Pacific Islands.”