A reader on reading - Alberto Manguel 2010

A reader in the looking-glass wood

Who am i?

“I am real!” said Alice, and began to cry.

“You won’t make yourself a bit realer by crying,”

Tweedledee remarked: “there’s nothing to cry about.”

“If I wasn’t real,” Alice said—half-laughing through her tears, it all seemed so ridiculous — “I shouldn’t be able to cry.”

“I hope you don’t suppose those are real tears?”

Tweedledum interrupted in a tone of great contempt.

Through the Looking-Glass, Chapter 4

A reader in the looking-glass wood

“Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the Cat.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Chapter 6

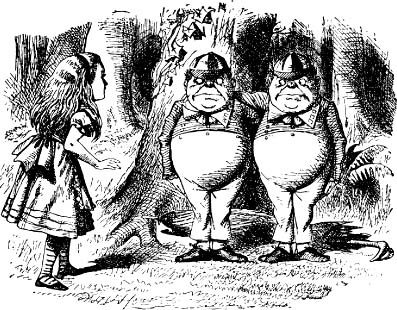

WHEN I WAS EIGHT OR NINE, in a house that no longer stands, someone gave me a copy of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. Like so many other readers, I have always felt that the edition in which I read a book for the first time remains, for the rest of my life, the original one. Mine, thank the stars, was enriched by John Tenniel’s illustrations and was printed on thick, creamy paper that reeked mysteriously of burnt wood.

There was much I didn’t understand in my first reading of Alice, but that didn’t seem to matter. I learned at a very early age that unless you are reading for some purpose other than pleasure (as we all sometimes must for our sins), you can safely skim over difficult quagmires, cut your way through tangled jungles, skip the solemn and boring lowlands, and simply let yourself be carried by the vigorous stream of the tale.

As far as I can remember, my first impression of the adventures was that of a physical journey on which I myself became poor Alice’s companion. The fall down the rabbit hole and the crossing through the looking-glass were merely starting points, as trivial and as wonderful as boarding a bus. But the journey! When I was eight or nine, my disbelief was not so much suspended as yet unborn, and fiction felt at times more real than everyday fact. It was not that I thought that a place such as Wonderland actually existed, but that I knew it was made of the same stuff as my house and my street and the red bricks that were my school.

A book becomes a different book every time we read it. That first childhood Alice was a journey, like the Odyssey or Pinocchio, and I have always felt myself a better Alice than a Ulysses or a wooden puppet. Then came the adolescent Alice, and I knew exactly what she had to put up with when the March Hare offered her wine when there was no wine at the table, or when the Caterpillar wanted her to tell him exactly who she was and what was meant by that. Tweedledee and Tweedledum’s warning that Alice was nothing but the Red King’s dream haunted my sleep, and my waking hours were tortured by exams in which Red Queen teachers asked me questions like “Take a bone from a dog: what remains?” Later, in my twenties, I found the trial of the Knave of Hearts collected in André Breton’s Anthologie de l’humour noir, and it became obvious that Alice was a sister of the surrealists; after a conversation with the Cuban writer Severo Sarduy in Paris, I was startled to discover that Humpty Dumpty owed much to the structuralist doctrines of Change and Tel Quel. And later still, when I made my home in Canada, how could I fail to recognize that the White Knight (“But I was thinking of a plan / To dye one’s whiskers green, / And always use so large a fan / That they could not be seen”) had found a job as one of the numerous bureaucrats that scurry through the corridors of every public building in my country?

In all the years during which I’ve read and reread Alice, I have come across many other different and interesting readings of her books, but I can’t say that any of these have become, in any deep sense, my own. The readings of others influence, of course, my personal reading, offer new points of view or color certain passages, but mostly they are like the comments of the Gnat who keeps naggingly whispering in Alice’s ear, “You might make a joke on that.” I refuse; I’m a jealous reader and will not allow others a jus primae noctis with the books that I read. The intimate sense of kinship established so many years ago with my first Alice has not weakened; every time I reread her, the bonds strengthen in very private and unexpected ways. I know other bits by heart. My children (my eldest daughter is, of course, called Alice) tell me to shut up when I burst, yet again, into the mournful strains of “The Walrus and the Carpenter.” And for almost every new experience, I find a premonitory or nostalgic echo in her pages, telling me once again, “This is what lies ahead of you” or “You have been here before.”

One adventure among many does not describe for me any particular experience I have had or may one day have but rather seems to address something vaster, an experience or (if the term is not too grand) a philosophy of life. It takes place at the end of Chapter 3 of Through the Looking-Glass. After passing through her reflection and making her way across the chessboard country that lies behind it, Alice reaches a dark wood where (she has been told) things have no names. “Well, at any rate it’s a great comfort,” she says bravely, “after being so hot, to get into the — into the — into what?” Astonished at not being able to think of the word, Alice tries to remember. “’I mean to get under the—under the—under this, you know!’ putting her hand on the trunk of a tree. ’What does it call itself, I wonder? I do believe it’s got no name — why, to be sure it hasn’t.’” Trying to recall the word for the place she is in, accustomed to putting into words her experience of reality, Alice suddenly discovers that nothing actually has a name: that until she herself can name something, that thing will remain nameless, present but silent, intangible as a ghost. Must she remember these forgotten names? Or must she make them up, brand new? Hers is an ancient conundrum.

After creating Adam “out of the dust of the ground” and placing him in a garden east of Eden (as the second chapter of Genesis tells us), God went on to create every beast of the field and every fowl of the air, and brought them to Adam to see what he would call them; and whatever Adam called every living creature, “that was the name thereof.” For centuries, scholars have puzzled over this curious exchange. Was Adam in a place (like the Looking-Glass Wood) where everything was nameless, and was he supposed to invent names for the things and creatures he saw? Or did the beasts and the fowl that God created indeed have names, which Adam was meant to know, and which he was to pronounce like a child seeing a dog or the moon for the first time?

And what do we mean by a “name”? The question, or a form of the question, is asked in Through the Looking-Glass. A few chapters after crossing the nameless wood, Alice meets the doleful figure of the White Knight, who, in the authoritarian manner of adults, tells her that he will sing a song to “comfort” her. “The name of the song,” says the Knight, “is called ’Haddocks’ Eyes’”:

“Oh, that’s the name of the song, is it?” Alice said, trying to feel interested.

“No, you don’t understand,” the Knight said, looking a little vexed. “That’s what the name is called. The name really is ’The Aged Aged Man.’ ”

“Then I ought to have said ’That’s what the song is called’?” Alice corrected herself.

“No, you oughtn’t: that’s quite another thing! The song is called ’Ways And Means’: but that’s only what it’s called, you know!”

“Well, what is the song then?” said Alice, who was by this time completely bewildered.

“I was coming to that,” the Knight said. “The song really is ’A-sitting On A Gate’: and the tune’s my own invention.”

As it turns out, the tune isn’t his own invention (as Alice points out) and neither are the Knight’s careful distinctions between what a name is called, the name itself, what the thing it names is called, and the thing itself; these distinctions are as old as the first commentators of Genesis. The world into which Adam was inducted was innocent of Adam; it was also innocent of Adam’s words. Everything Adam saw, everything he felt, as everything he fancied or feared, was to be made present to him (as, eventually, to every one of us) through layers of names, names with which language tries to clothe the nakedness of experience. It is not by chance that once Adam and Eve lost their innocence, they were obliged to wear skins “so that,” says a Talmudic commentator, “they might learn who they were through the shape that enveloped them.” Words, the names of things, give experience its shape.

The task of naming belongs to every reader. Others who do not read must name their experience as best they can, constructing verbal sources, as it were, by imagining their own books. In our book-centered societies, the craft of reading signals our entrance into the ways of the tribe, with its particular codes and demands, allowing us to share the common source of recorded words; but it would be a mistake to think of reading as a merely receptive activity. On the contrary: Stéphane Mallarmé proposed that every reader’s duty was “to purify the sense of the words of the tribe.” To do this, readers must make books theirs. In endless libraries, like thieves in the night, readers pilfer names, vast and marvelous creations as simple as “Adam” and as far-fetched as “Rumpelstiltskin.” Dante describes his encounter with the three beasts in a dark forest, “in the middle of the road of life;” for his readers that half-run life becomes their own, and also a mirror of another forest, a place they once saw in childhood, a forest that fills their dreams with scents of pine and fox. John Bunyan describes Christian running from his house with his fingers in his ears so as not to hear the pleas of his wife and children, and Homer describes Ulysses, bound to the mast, forced to listen to the sirens’ song; the reader of Bunyan and Homer applies these words to the deafness of our contemporary, the amiable Prufrock. Edna St. Vincent Millay calls herself “domestic as a plate,” and it is the reader who renames the daily kitchen china, the companion of our meals, with a newly acquired meaning. “Man’s innate casuistry!” complained Karl Marx (as quoted by Friedrich Engels in The Origins of the Family): “To change things by changing their names!” And yet, pace Marx, that is exactly what we do.

As every child knows, the world of experience (like Alice’s wood) is nameless, and we wander through it in a state of bewilderment, our heads full of mumblings of learning and intuition. The books we read assist us in naming a stone or a tree, a moment of joy or despair, the breathing of a loved one or the kettle whistle of a bird, by shining a light on an object, a feeling, a recognition and saying to us that this here is our heart after too long a sacrifice, that there is the cautionary sentinel of Eden, that what we heard was the voice that sang near the Convent of the Sacred Heart. These illuminations sometimes help; the order in which experiencing and naming take place does not much matter. The experience may come first and, many years later, the reader will find the name to call it in the pages of King Lear. Or it may come at the end, and a glimmer of memory will throw up a page we had thought forgotten in a battered copy of Treasure Island. There are names made up by writers that a reader refuses to use because they seem wrongheaded, or trite, or even too great for ordinary understanding, and are therefore dismissed or forgotten or kept for some crowning epiphany that (the reader hopes) will one day require them. But sometimes they help the reader name the unnamable. “You want him to know what cannot be spoken, and to make the perfect reply, in the same language,” says Tom Stoppard in The Invention of Love. Sometimes a reader can find on a page that perfect reply.

The danger, as Alice and her White Knight knew, is that we sometimes confuse a name and what we call a name, a thing and what we call a thing. The graceful phantoms on a page, with which we so readily tag the world, are not the world. There may be no names to describe the torture of another human being, the birth of one’s child. After creating the angels of Proust or the nightingale of Keats, the writer can say to the reader, “Into your hands I commend my spirit,” and leave it at that. But how are readers to be guided by these entrusted spirits to find their way in the ineffable reality of the wood?

Systematic reading is of little help. Following an official book list (of classics, of literary history, of censored or recommended reading, of library catalogues) may, by chance, throw up a useful name, as long as we bear in mind the motives behind the lists. But the best guides, I believe, are the reader’s whims—trust in pleasure and faith in haphazardness — which sometimes lead us into a makeshift state of grace, allowing us to spin gold out of flax.

Gold out of flax: in the summer of 1935 the poet Osip Mandelstam was granted by Stalin, supposedly as a favor, identity papers valid for three months, accompanied by a residence permit. According to his wife, Nadezhda Mandelstam, this little document made their lives much easier. It happened that a friend of the Mandelstams, the actor and essayist Vladimir Yakhontov, chanced to come through their city. In Moscow he and Mandelstam had amused themselves by reading from ration books, in an effort to name paradise lost. Now the two men did the same thing with their identity papers. The scene is described in Nadezhda’s memoir Hope Against Hope: “It must be said that the effect was even more depressing. In the ration book they read off the coupons solo and in chorus: ’Milk, milk, milk … cheese, meat …’ When Yakhontov read from the identity papers, he managed to put ominous and menacing inflections in his voice: ’Basis on which issued … issued … by whom issued … special entries … permit to reside, permit to reside, permit to re-side …’ ”

All true readings are subversive, against the grain, as Alice, a sane reader, discovered in the Looking-Glass world of mad name givers. The Duchess calls mustard “a mineral;” the Cheshire Cat purrs and calls it “growling;” a Canadian prime minister tears up the railway and calls it “progress;” a Swiss businessman traffics in loot and calls it “commerce;” an Argentinean president shelters murderers and calls it “amnesty.” Against such misnomers readers can open the pages of their books. In such cases of willful madness, reading helps us maintain coherence in the chaos. Not to eliminate it, not to enclose experience within conventional verbal structures, but to allow chaos to progress creatively on its own vertiginous way. Not to trust the glittering surface of words but to burrow into the darkness.

The impoverished mythology of our time seems afraid to go beneath the surface. We distrust profundity, we make fun of dilatory reflection. Images of horror flick across our screens, big or small, but we don’t want them slowed down by commentary: we want to watch Gloucester’s eyes plucked out but not to have to sit through the rest of Lear. One night, some time ago, I was watching television in a hotel room, zapping from channel to channel. Perhaps by chance, every image that held the screen for a few seconds showed someone being killed or beaten, a face contorted in anguish, a car or a building exploding. Suddenly I realized that one of the scenes I had flicked past did not belong to a drama series but to a newscast on war in the Balkans. Among the other images which cumulatively diluted the horror of violence, I had watched, unmoved, a real person being hit by a real bullet.

George Steiner suggested that the Holocaust translated the horrors of our imagined hells into a reality of charred flesh and bone; it may be that this translation marked the beginning of our modern inability to imagine another person’s pain. In the Middle Ages, for instance, the horrible torments of martyrs depicted in countless paintings were never viewed simply as images of horror: they were illumined by the theology (however dogmatic, however catechistic) that bred and defined them, and their representation was meant to help the viewer reflect on the world’s ongoing suffering. Not every viewer would necessarily see beyond the mere prurience of the scene, but the possibility for deeper reflection was always present. After all, an image or a text can only offer the choice of reading further or more profoundly; this choice the reader or viewer can reject since in themselves text and image are nothing but dabs on paper, stains on wood or canvas.

The images I watched that night were, I believe, nothing but surface; like pornographic texts (political slogans, Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho, advertising pap), they offered nothing but what the senses could apprehend immediately, all at once, fleetingly, without space or time for reflection.

Alice’s Looking-Glass Wood is not made up of such images: it has depth, it requires thought, even if (for the time of its passing) it offers no vocabulary to name its proper elements. True experience and true art (however uncomfortable the adjective has become) have this in common: they are always greater than our comprehension, even than our capabilities of comprehension. Their outer limit is always a little past our reach, as the Argentinean poet Alejandra Pizarnik once described:

And if the soul were to ask, Is it still far? you must answer:

On the other side of the river, not this one, the one just beyond.

To come even this far, I have had many and marvelous guides. Some overwhelming, others more intimate, many vastly entertaining, a few illuminating more than I could hope to see. Their writing keeps changing in the library of my memory, where circumstances of all sorts — age and impatience, different skies and different voices, new and old commentaries — keep shifting the volumes, crossing out passages, adding notes in the margins, switching jackets, inventing titles. The furtive activity of such anarchic librarians expands my limited library almost to infinity: I can now reread a book as if I were reading one I had never read before.

In Bush, his house in Concord, the seventy-year-old Ralph Waldo Emerson began suffering from what was probably Alzheimer’s disease. According to his biographer Carlos Baker: “Bush became a palace of forgetting…. [But] reading, he said, was still an ’unbroken pleasure.’ More and more the study at Bush became his retreat. He clung to the comforting routine of solitude, reading in his study till noon and returning again in the afternoon until it was time for his walk. Gradually he lost his recollection of his own writings, and was delighted at rediscovering his own essays: ’Why, these things are really very good,’ he told his daughter.”

Something like Emerson’s rediscovery happens now when I take down The Man Who Was Thursday or Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and meet them like Adam greeting his first giraffe.

Is this all?

Sometimes it seems enough. In the midst of uncertainty and many kinds of fear, threatened by loss, change, and the welling of pain within and without for which one can offer no comfort, readers know that at least there are, here and there, a few safe places, as real as paper and as bracing as ink, to grant us roof and board in our passage through the dark and nameless wood.