A reader on reading - Alberto Manguel 2010

Reading white for black

Books as business

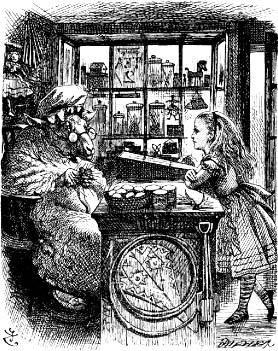

“I should like to buy an egg, please,” she said timidly.

“How do you sell them?”

“Fivepence farthing for one—twopence for two,” the

Sheep replied.

“Then two are cheaper than one?” Alice said in a surprised

tone, taking out her purse.

“Only you must eat them both, if you buy two,” said the

Sheep.

Through the Looking-Glass, Chapter 5

Reading white for black

“Do you know Languages? What’s French for fiddle-de-dee?”

“Fiddle-de-dee’s not English,” Alice replied gravely.

“Who ever said it was?” said the Red Queen.

Through the Looking-Glass, Chapter 9

For Christine Le Boeuf

THROUGHOUT PART OF 1992 AND 1993, I worked on the translation of three short stories by Marguerite Yourcenar. The stories, published in French under the title Conte bleu, which I rendered in English as A Blue Tale, are early works by the writer who was to become in later life such an accomplished stylist. Understandably, because they were written with the exuberance and know-all of youth, the stories stray from time to time from sober blue to lurid purple. Since translators, unlike writers and God Himself, have the possibility of amending the faults of the past, it seemed to me that to preserve every glitter and volute of Yourcenar’s young text would have been nothing but a pedantic undertaking, less intended for lovers of literature than for literary archaeologists. Furthermore, the English language is less patient with ebullience than French. And so it was that a few times—mea culpa, mea maxima culpa—I silently clipped an adjective or pruned a simile.

Vladimir Nabokov, criticized by his friend Edmund Wilson for producing a translation of Eugene Onegin “with warts and all,” responded that the translator’s business was not to improve or comment on the original but to give the reader ignorant of one language a text recomposed in all the equivalent words of another. Nabokov apparently believed (though I find it hard to imagine that the master craftsman meant this) that languages are “equivalent” in both sense and sound, and that what is imagined in one language can be reimagined in another—without an entirely new creation taking place. But the truth is (as every translator finds out at the beginning of the first page) that the phoenix imagined in one language is nothing but a barnyard chicken in another, and to invest that singular fowl with the majesty of the bird born from its own ashes, a different language might require the presence of a different creature, plucked from bestiaries that possess their own notions of strangeness. In English, for instance, the word phoenix still has a wild, evocative ring; in Spanish, ave fénix is part of the bombastic rhetoric inherited from the seventeenth century.

In the early Middle Ages, translation (from the past participle of the Latin transferre, “to transfer”) meant conveying the relics of a saint from one place to another. Sometimes these translations were illegal, as when saintly remains were stolen from one town and carried away for the greater glory of another, which is how the body of Saint Mark was transferred from Constantinople to Venice, hidden under a cartful of pork, which the Turkish guards at Constantinople’s gates refused to touch. Carrying away something precious and making it one’s own by whatever means possible: this definition serves the act of literary translation perhaps better than Nabokov’s.

No translation is ever innocent. Every translation implies a reading, a choice both of subject and interpretation, a refusal or suppression of other texts, a redefinition under the terms imposed by the translator, who, for the occasion, usurps the title of author. Since a translation cannot be impartial, any more than a reading can be unbiased, the act of translation carries with it a responsibility that extends far beyond the limits of the translated page, not only from language to language but often within the same language, from genre to genre, or from the shelves of one literature to those of another. In this not all “translations” are acknowledged as such: when Charles and Mary Lamb turned Shakespeare’s plays into prose tales for children, or when Virginia Woolf generously herded Constance Garnett’s versions of Turgenev “into the fold of English Literature,” the displacements of the text into the nursery or into the British Library were not regarded as “translations” in the etymological sense. Lamb or Woolf, every translator disguises the text with another, attractive or detractive meaning.

Were translation a simple act of pure exchange, it would offer no more possibilities for distortion and censorship (or improvement and enlightening) than photocopying or, at most, scriptorium transcription. But that isn’t so. If we acknowledge that every translation, simply by transferring the text to another language, space, and time, alters it for better or for worse, then we must also acknowledge that every translation — transliteration, retelling, relabeling

—adds to the original text a prêt-à-porter reading, an implicit commentary. And that is where the censor comes in.

That a translation may hide, distort, subdue, or even suppress a text is a fact tacitly recognized by the reader who accepts it as a “version” of the original, a process Joachim de Bellay described in 1549, in his Défense et exemple de la langue française: “And what shall I say of those more properly called traitors than translators, since they betray those whom they aim to reveal, tarnishing their glory, and seducing ignorant readers by reading white for black?”

In the index to John Boswell’s groundbreaking book on homosexuality in the Middle Ages, Christianity, Social Tolerance and Homosexuality, the entry for “Translation” reads, “See Mistranslation” — or what Boswell calls “the deliberate falsification of historical records.” The instances of asepticized translations of Greek and Roman classics are too numerous to mention and range from a change of pronoun which willfully conceals the sexual identity of a character to the suppression of an entire text, such as the Amores of the Pseudo-Lucian, which Thomas Francklin in 1781 deleted from his English translation of the author’s works because it included an explicit dialogue among a group of men on whether women or boys were erotically more desirable. “But as this is a point which, at least in this nation, has been long determined in favour of the ladies, it stands in need of no further discussion,” wrote the censorious Francklin.

“We can only prohibit that which we can name,” wrote George Steiner in After Babel. Throughout the nineteenth century, the classic Greek and Roman texts were recommended for the moral education of women only when purified in translation. The Reverend J. W. Burgon made this explicit when in 1884, from the pulpit of New College, Oxford, he preached against allowing women into the university, where they would have to study the texts in the original. “If she is to compete successfully with men for ’honours’ “ (wrote the timorous reverend), “you must needs put the classic writers of antiquity unreservedly into her hands—in other words, must introduce her to the obscenities of Greek and Roman literature. Can you seriously intend it? Is it then a part of your programme to defile that lovely spirit with the filth of old-world civilisation, and to acquaint maidens in their flower with a hundred abominable things which women of any age (and men too, if that were possible) would rather a thousand times be without?”

It is possible to censor not only a word or a line of text through translation but also an entire culture, as has happened time and again throughout the centuries among conquered peoples. Towards the end of the sixteenth century, for instance, the Jesuits were authorized by King Philip II of Spain, champion of the Counter-Reformation, to follow in the steps of the Franciscans and establish themselves in the jungles of what is now Paraguay. From 1609 until their expulsion from the colonies in 1767, the Jesuits created settlements for the native Guaranis, walled communities called reducciones because the men, women, and children who inhabited them were “reduced” to the dogmas of Christian civilization. The differences between conquered and conquerors were, however, not easily overcome. “What makes me a pagan in your eyes,” said a Guarani shaman to one of the missionaries, “is what prevents you from being a Christian in mine.” The Jesuits understood that effective conversion required reciprocity and that understanding the other was the key that would allow them to keep the pagans in what was called, borrowing from the vocabulary of Christian mystic literature, “concealed captivity.” The first step to understanding the other was learning and translating the other’s language.

A culture is defined by that which it can name; in order to censor, the invading culture must also possess the vocabulary to name those things belonging to the other. Therefore, translating into the tongue of the conqueror always carries within the act the danger of assimilation or annihilation; translating into the tongue of the conquered, the danger of overpowering or undermining. These inherent conditions of translation extend to all variations of political imbalance. Guarani (still the language spoken, albeit in a much altered form, by more than a million Paraguayans) had been until the arrival of the Jesuits an oral language. It was then that the Franciscan Fray Luis de Bolanos, whom the natives called “God’s wizard” because of his gift for languages, compiled the first Guarani dictionary. His work was continued and perfected by the Jesuit Antonio Ruiz de Montoya, who after several years’ hard labor gave the completed volume the title of Tesoro de la lengua guarani (Thesaurus of the Guarani Tongue). In a preface to a history of the Jesuit missions in South America, the Paraguayan novelist Augusto Roa Bastos noted that in order for the natives to believe in the faith of Christ, they needed, above all, to be able to suspend or revise their ancestral concepts of life and death. Using the Guaranis’ own words, and taking advantage of certain coincidences between the Christian and Guarani religions, the Jesuits retranslated the Guarani myths so that they would foretell or announce the truth of Christ. The Last-Last-First-Father, Namandu, who created His own body and the attributes of that body from the primordial mists, became the Christian God from the book of Genesis; Tupa, the First Parent, a minor divinity in the Guarani pantheon, became Adam, the first man; the crossed sticks, yvyráyuasá, which in the Guaraní cosmology sustain the earthly realm, became the Holy Cross. And conveniently, since Ñamandú’s second act was to create the word, the Jesuits were able to infuse the Bible, translated into Guaraní, with the accepted weight of divine authority.

In translating the Guaraní language into Spanish, the Jesuits attributed to certain terms that denoted acceptable and even commendable social behavior among the natives the connotation of that behavior as perceived by the Catholic Church or the Spanish court. Guaraní concepts of private honor, of silent acknowledgment when accepting a gift, of a specific as opposed to a generalized knowledge, and of a social response to the mutations of the seasons and of age, were translated bluntly and conveniently as “Pride,” “Ingratitude,” “Ignorance,” and “Instability.” This vocabulary allowed the traveler Martin Dobrizhoffer of Vienna to reflect, sixteen years after the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1783, in his Geschichte der Abiponer (History of the Abiponer People), on the corrupt nature of the Guaranís: “Their many virtues, which certainly belong to rational beings, capable of culture and learning, serve as frontispiece to very irregular compositions within the works themselves. They seem like automata in whose making have been joined elements of pride, ingratitude, ignorance, and instability. From these principal sources flow the brooks of sloth, drunkenness, insolence, and distrust, with many other disorders which stultify their moral quality.”

In spite of Jesuit claims, the new system of beliefs did not contribute to the happiness of the natives. Writing in 1769, the French explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville described the Guaraní people in these laconic words: “These Indians are a sad lot. Always trembling under the stick of a pedantic and stern master, they possess no property and are subjected to a laborious life whose monotony is enough to kill a man with boredom. That is why, when they die, they don’t feel any regret in leaving this life.”

By the time of the expulsion of the Jesuits from Paraguay, the Spanish chronicler Fernández de Oviedo was able to say of those who had “civilized” the Guaraní people what a Briton, Calgacus, is reported to have said after the Roman occupation of Britain: “The men who have perpetuated these acts call these conquered places ’peaceful.’ I feel they are more than peaceful — they are destroyed.”

Throughout history, censorship in translation has also taken place under more subtle guises, and in our time, in certain countries, translation is one of the means by which “dangerous” authors are submitted to cleansing purges.

(The Brazilian Nélida Piñón in Cuba, the decadent Oscar Wilde in Russia, Native American chroniclers in the United States and Canada, the French enfant terrible Georges Bataille in Franco’s Spain have all been published in truncated versions. And in spite of all my good intentions, could not my version of Yourcenar be considered censorious?) Often, authors whose politics might be read uncomfortably are simply not translated and authors with a difficult style are either passed over in favor of others more easily accessible or condemned to weak or clumsy versions of their work.

Not all translation, however, is corruption and deceit. Sometimes cultures can be rescued through translation, and translators become justified in their laborious and menial pursuits. In January 1976, the American lexicographer Robert Laughlin sank to his knees in front of the chief magistrate of the town of Zinacantán in southern Mexico and held up a book that had taken Laughlin fourteen years to compile: the great Tzotzil dictionary that rendered into English the Mayan language of 120,000 natives of Chiapas, known also as the “People of the Bat.” Offering the dictionary to the Tzotzil elder, Laughlin said, in the language he had so painstakingly recorded, “If any foreigner comes and says that you are stupid, foolish Indians, please show him this book, show him the 30,000 words of your knowledge, your reasoning.”

It should, it must, suffice.