It was the best of sentences, it was the worst of sentences - June Casagrande 2010

The writer and his father lamented his ineptitude: Unclear antecedents

In the title of this chapter, "The Writer and His Father Lamented His Ineptitude," it's clear that someone is inept. The problem is we don't know who. His could refer to the writer or to his father. In the context of this book, it's a safe bet that we would be more focused on the writer. So we can guess that Sonny Boy is the one being slammed in this sentence. But the grammar doesn't confirm this. So we can't be sure. The possibility remains it could be Dad whose shortcomings are being lamented.

This problem is called an unclear antecedent. At its worst, this problem can completely ruin a written work:

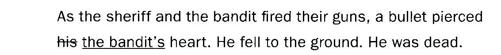

As the sheriff and the bandit fired their guns, a bullet pierced his heart. He fell to the ground. He was dead.

From the first sentence, we can't know whether it was the good guy or the bad guy who died. From the sentences that follow, it's clear that it will take a while for us to find out. Maybe we never will.

The passage is confusing and annoying and can be enough to make a Reader close a book or put down a manuscript forever.

Happily, these problems are easy to avoid. First, remember the lessons of our chapter on the. The Reader isn't in your head. Second, remember to pay careful attention to your pronouns—especially on the reread. This includes

• subject pronouns: I, you, he, she, it, we, they

• object pronouns: me, you, him, her, it, us, them

• possessive pronouns: mine, yours, his, hers, its, ours, theirs

• possessive determiners (think of these as adjective forms of possessive pronouns): my, your, his, her, its, our, their

• relative pronouns: that, which, who, whom

Of course, the first-person forms like I and me don't pack as much danger as third-person forms like his, her, hers, their, theirs, and so on. That's because usually fewer people could be I than could be he. So there's less chance of confusion.

Don't let the term unclear antecedent intimidate you. It means exactly what it sounds like: that it's unclear which prior thing is being referred to. In Bubba lost his car keys, the word his is a possessive determiner. Its antecedent—the thing to which it refers—is Bubba. So the Reader can see that you're talking about Bubba's keys.

For pronouns like he and his, unclear antecedents are very easy to create. You know whether it was the sheriff or the bandit who got shot, you just forgot that the Reader does not. It can happen to anyone. Just be sure to catch them when you reread your work. Make it a habit to scrutinize every him, her, and so on, to be sure they're clear.

When they're not, they're easy to fix:

As the sheriff and the bandit fired their guns, a bullet pierced

his the bandit's heart. He fell to the ground. He was dead.

Notice that we left he in the last two sentences. It's clear that he is the bandit. The Reader gets that.

Of course, we can imagine scenarios in which that he might not be so clear. If the bandit got shot just two sentences after the sheriff got shot, then it may not be clear at all to your Reader which one fell to the ground. But again, see how the Reader is your guiding light? It's almost as though he is helping you. Call it paradox, call it karma, call it a variation on AA members' belief that helping others helps them stay sober. Whatever. Just remember its power.

Not all pronouns are as easy to work with as personal pronouns like he and him. Take it. Unlike pronouns that refer to specific people, the pronoun it can refer to vague things like ideas. Compare these two uses of it:

The car is parked. It is in a handicapped space.

Jenna knows math. It is why she landed this job.

It is a pronoun like any other. It stands in for a noun. In the first example, the antecedent of it is clearly the car. But in our second example, what noun, exactly, does it represent? Jenna? Nope. Math? Nope. That leaves just knows, but that's a conjugated verb—an action under way. How can a pronoun refer to a verb? Easy: if, in the writer's head, it stands in for knowing, then that's what it means. The antecedent is implied. It could be the gerund knowing, as in, Knowing math is why Jenna landed this job. It could be an implied noun like

The fact that Jenna knows math is why she landed the job or Jenna's knowledge of math is why she landed the job.

That and which are two other pronouns that create problems:

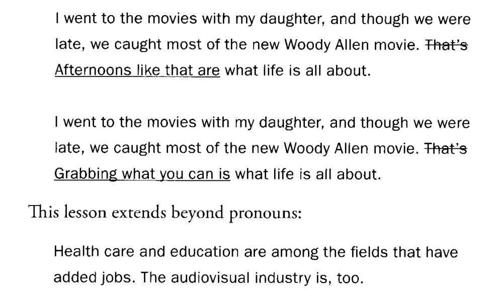

I went to the movies with my daughter, and though we were late, we caught most of the new Woody Allen movie. That's what life is all about.

What is what life is all about? Spending time with your daughter? Being late? Grabbing what you can out of a bad situation? Woody Allen? The slice of life created by combining all these elements? The writer should be clearer:

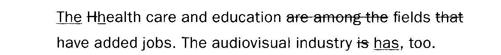

This isn't wrong per se, but it causes me to do a double take. The audiovisual industry is what? It takes a moment to realize that the writer omitted part of the second sentence. The industry is among the fields. There's nothing wrong with leaving things implied

as long as the implication is clear and doesn't make your Reader stumble:

Kelly is crazy. Ryan is, too.

Implications only work if the Reader gets them. We don't say what Ryan is. We leave it implied. Yet it's perfectly clear. He's crazy.

When I look at the prior example about health care and education, what's most interesting to me is how the writer set herself up for trouble. Had she aimed for something less wordy than that whole are among the structure, the sentence would have been clear.

Whenever you use a pronoun or leave a noun merely implied, just be sure it's clear what you're talking about. If there's any doubt, say outright whatever you had wanted to imply. Returning to an earlier example:

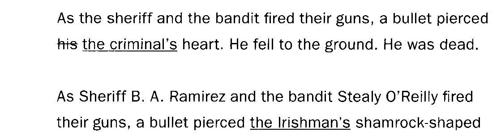

A lot of writers avoid stuff like this because they worry it sounds redundant. By all means, if you can find alternative wording you like, use it:

heart. He fell to the ground, spilling his bottle of Guinness. He was dead as the corpse in Finnegans Wake. There'd be no pot of gold at the end of his rainbow—no sweet bowl of Lucky Charms with its yellow moons, orange stars, and green clovers.

You get the idea.

Pick any wording you choose. But when you can find no synonyms or other embellishments to point squarely at your antecedent, repetitiveness is better than chaos. It's better to repeat the word bandit than to refuse to tell your Reader which one of your pivotal characters met his demise.