It was the best of sentences, it was the worst of sentences - June Casagrande 2010

Trimming the fat: Expressions that weigh down your sentences

In Reading Like a Writer, Francine Prose excerpts the first sentence of Samuel Johnson's The Life of Savage. The sentence is 134 words long. But Prose, a veteran writing teacher, doesn't criticize Johnson's monster sentence. She praises it. Her reason: The sentence, Prose says, is "economical."

The term economy of words crops up a lot in newspaper editing. When you're cranking out a hundred thousand copies a day on none-too-cheap newsprint, you're no fan of wasted ink. So, for as long as papers are printed on paper, there will continue to be a startling correlation between "all the news that's fit to print" and "all the news that fits." But economy of words is no less a virtue in an online article or an eight-hundred-page saga about hobbits or alien overlords. Why, you ask? I'll give you a moment to answer your own question. That's right. Because of the Reader. His time is valuable, his attention span may be short, his opportunities for diversions are infinite, and his willingness to read your writing is a blessing for which you should be grateful.

Don't waste his time. Learn to root out flabby writing and to streamline sentences to make every word count.

There's a difference between fatty sentences and long sentences. Yes, they're often one and the same. But not always. A 134-word sentence can be tight and economical, while an 8-word sentence can contain 7 words of lard—or even 8.

Keeping the blubber out of your sentences is no easy feat. Fatty prose sneaks into writing in many ways. It can take the form of an unnecessary adverb, a ridiculous redundancy, a self-conscious over-explaining, a cliche, or jargon. You should develop the habit of always considering whether your sentence would be better if you chopped out or swapped out a word, phrase, or clause. Develop the habit of considering whether each sentence is itself an asset or a liability.

In this chapter, we'll look at the fatty sentence problems that are easiest to fix—the unnecessary words and verbose little insertions that so often plague writers. We'll also look at the scary-sounding but really quite simple concepts of run-on sentences and comma splices. We'll save the deeper structural problems for the next chapter.

Adjectives can contribute to fatty prose. Considering how indispensable they are, that's surprising. Yet, often, they're dead weight.

Take, for example, this much-maligned first sentence of The Da Vinci Code:

Renowned curator Jacques Sauniere staggered through the vaulted archway of the museum's Grand Gallery.

There are two adjectives in this sentence, not counting Grand, which is part of a proper name. One of our two adjectives is fine. The other is—I'm not the first to say it—terrible.

Vaulted is serviceable. Not good, not bad. It may help some Readers make a mental picture. To others it may add nothing to archway. But it's justified.

Renowned, however, stinks. And that's not just my opinion. Linguist Geoffrey Pullum has made the same observation: this Da Vinci Code sentence contains a classic example of an adjective trying to stand in for real information. Remember, this is the first sentence of the book, and already the author is telling us what to think about one of his characters and shirking his due diligence to show us why this character is renowned.

So what's the alternative to The Da Vinci Code's approach? Let's look at some other writers' choices:

In the late summer of 1922, my grandmother Desdemona Stephanides wasn't predicting births but deaths, specifically, her own.

In this passage from Middlesex, Jeffrey Eugenides doesn't say my eccentric grandmother, my hypochondriac grandmother, or my neurotic grandmother. Within a few sentences, it will become clear that she is all those things: "Desdemona became what she'd remain for the rest of her life: a sick person imprisoned in a healthy body." Eugenides didn't need to slap an adjective in front of grandmother to make his point.

Let's look at another example of an adjective that never was:

It's somewhere above Nebraska I remember I left my fish behind.

Chuck Palahniuk could have written my beloved fish or even my beloved butterscotch-colored fish. He didn't. He started chapter 39 of Survivor with that simple sentence, then waited awhile to add, "It's crazy, but you invest all your emotion in just this one tiny goldfish, even after six hundred and forty goldfish, and you can't just let the little thing starve to death." That's how we know that it's beloved and that it's gold.

In other words, perhaps the best way to fix our Da Vinci Code sentence is to get rid of the adjective renowned altogether—maybe even get rid of the modifying noun curator and the adjective vaulted—and wait for a better opportunity to convey the information. No doubt, that's what some more critically acclaimed writers would have done:

Jacques Sauniere staggered through the archway of the museum's Grand Gallery.

Adjectives aren't bad. They can be wonderful, and as predicates they can work perfectly: Frau Helga was tall.

But adjectives are no substitute for solid information. Often they have that less-is-more thing working against them: The big, terrifying, homicidal, totally out-of-control escaped convict ran toward me does not achieve its desired effect. Better to just say, The escaped convict ran toward me and leave it at that.

If it helps, divide adjectives into two categories: facts and value judgments. Adjectives that express fact can be fine. But adjectives that impose value judgments on your Reader are trouble. Bloodied and limping curator Jacques Sauniere, though awkward, is still better than Awesome and brilliant curator Jacques Sauniere.

Worse, sometimes adjectives are meaningless. The exact same means the same. The only difference is that in the exact same, it's clear the writer is trying to pound home her point. As we know, this can backfire, weakening the point.

If all this talk about adjectives reminds you of our adverbs chapter, there's a good reason for that. Adjectives and adverbs carry the same risks. Here's an example:

The freshly rejuvenated $70-million Sands Resort & Spa hearkens to Vegas's glory days.

Unless you're actively trying to root out wasteful words, you might not notice that the word freshly modifying rejuvenated is about as meaningful as freshly refreshed. Pure redundancy.

Look at the sentence without the goldbricking adverb:

The rejuvenated $70-million Sands Resort & Spa hearkens to Vegas's glory days.

The freshly had a brain-numbing effect, as if the writer used it just to meet a word count minimum. The streamlined version, though just one word shorter, emphasizes substance. It has more power to command the Reader's attention.

As we saw in chapter 7, manner adverbs can backfire, making an idea seem weak even as it struggles to make it strong. But adverbs can also create redundancies: already existing, previously done, first begin, currently working.

Of course, adverbs need not be redundant to be flabby:

Sarah quickly grabbed a knife. Sarah grabbed a knife.

Does quickly really add anything to the sentence? Or does the less-is-more principle render the second sentence better? Some may disagree, and there may be times when quickly adds a crucial bit of information. But to me this sentence better conveys immediacy without the word quickly.

Watch out for manner adverbs that add no solid information: extremely, very, really, incredibly, unbelievably, astonishingly, totally, truly, currently, presently, formerly, previously.

Also watch out for ones that try too hard to add impact to actions: cruelly, happily, wantonly, angrily, sexily, alluringly, menacingly, blissfully.

All these words have their place. They appear in the best writing, but more often they're found in the worst writing. So consider them red flags and weigh their use carefully.

Adverbs and adjectives aren't the only flabby accessories that show up in writing. Here's an example modeled after a real sentence I came across in my copyediting work:

In addition to on-the-clock volunteer opportunities, ABC Co. also offers standard healthcare benefits, adoption assistance and flexible scheduling to help employees cultivate work/life balance.

I hate in addition to. Don't get me wrong, I write it all the time. And only about half the time do I remember that Writer June is doing something Reader June can't stand. But just because I'm guilty of this one doesn't mean I have much sympathy for the writer who throws an unnecessary in addition to my way.

Not every in addition to is bad. Sometimes it's a valid choice. But usually, in addition to refers to something that's already been discussed at length. In our sample sentence, it's clear that the reader already knows something about the on-the-clock volunteer opportunities being discussed. Chances are that the writer just finished discussing them and was looking for a segue to the next topic. In other words, she was saying, "In addition to the stuff I just told you about, here's another thing."

You can achieve the same effect by saying, Here's another thing. Or better yet, just get to the other thing.

This brings us to another problem with our original sentence: The in addition to phrase introduces a clause that contains the word also. This is a redundancy. It renders the entire in addition to phrase a complete waste. The writer should have simply said,

ABC Co. also offers standard healthcare benefits, adoption assistance and flexible scheduling to help employees cultivate work/life balance.

We could also ask, Do we need to say to help employees cultivate work/life balance? The answer is more subjective, but it's worth considering whether we should chop it out.

There are a lot of other little phrases that, like in addition to, can be pure fat. In the original Elements of Style, William Strunk Jr. told his Cornell students, "Omit needless words," then went on to list examples. "The question as to whether," Strunk wrote, can be just "whether." "Used for fuel purposes" can be "used for fuel." "This is a subject which" can be just "this subject."

Strunk was especially emphatic with his students about the fact (hat: "The expression the fact that should be revised out of every sen-tence in which it occurs."

The Elements of Style was not written as a book of universal writing laws. It was a classroom style guide for Strunk's Cornell students. So you can discard any advice in it you don't agree with. But there's some wisdom you can use here. Consider whether these expressions are indeed needless, and if so, delete them.

I'm more liberal on the fact that. Sometimes it's the best way to show that an abstract concept is functioning as a noun:

That Robbie steals means he's a thief.

The fact that Robbie steals means he's a thief.

Because the fact is a noun phrase, it's more easily recognized as a subject than the subordinate clause that Robbie steals. Still, there's wisdom in the traditional caveat. The fact that is often pure lard. Use it as a measure of last resort after you've considered recasting the sentence:

Because Robbie steals, he's a thief.

I'm more conservative on due to the fact that. That's just a tedious way of saying because.

Other flabby figures of speech to watch out for include in terms of for his part, he is a man who, the exact same, taking into account, as if this weren't enough, considering all that—the list goes on.

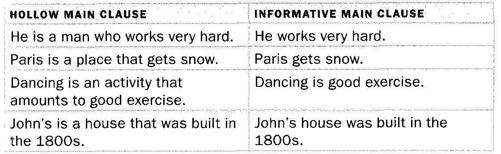

He is a man who and other terms with this structure are especially troubling: It is a place that, dancing is an activity that, John's is a house that, cooking is a thing that. They all follow the form

noun/pronoun + to be + noun/pronoun that refers to the

same thing as first + relative pronoun

This structure shifts the focus away from the important stuff by dedicating the main clause to ridiculously obvious information:

He is a man who works very hard.

Paris is a place that gets snow.

Dancing is an activity that amounts to good exercise.

John's (house) is a house that was built in the 1800s.

In all these sentences, the new information is trapped in the relative clause—those clauses that begin with that, which, who, or whom and that we learned about in chapter 8. The main clause is devoid of new information. It has the same problem as the upside-down subordination we covered in chapter 2 because the most interesting information isn't getting top billing in the sentence.

To fix a sentence with this structure, just make the new information your main clause:

Keep your eyes peeled for this construction and be prepared to correct it.

Here's another term that is often a waste of ink: for his part. You'd think it would be rare. But I've seen it quite a few times in my copy-editing work. This is a slight alteration of a real sentence I copyedited:

For Brady's part, as the director of the Center for Computer Security at the Information Institute at the university, emphasis is on training students for the programming path.

This sentence has a number of problems, but none so glaring or so easily fixed as for Brady's part. For Brady says the same thing with fewer words. In fact, I can't think of a situation in which for so-and-so's part is better than just for so-and-so.

And here's an oddball little construction that crops up a lot in feature writing: from blank to blank. There's nothing wrong with from . . . to constructions, so it astounds me that they're so often the culprit in bad sentences. Here are some examples I've run across in my copyediting work:

Everything from what software will be needed to how someone will book a trip and pay needs to be developed for the business.

From donating a few hours weekly to nearby hospitals to participating in breast or ovarian cancer walks to raise research funds, millions of us donate our time and skills to myriad organizations and causes.

And here's one with a double whammy of in addition to and. from ... to:

In addition to being the epicenter of bridal up-dos for those getting married on the expansive lawns, the Alex Remo Salon also caters to stressed-out guests with a comprehensive menu of facials, which range from the Moisturizing Hydration Facial, which utilizes protein, essential oils and active serums to relieve dry and sensitive skin; to the Star Facial, a 75-minute microdermabrasion session that reduces the appearance of scars, fine lines and wrinkles.

Yep. Those are all real sentences with a few names changed to protect the innocent. (Didn't believe me when I told you that from ... to constructions are a common problem in feature writing, did you?)

A from ... to construction can set up a very long introductory phrase. The main clause has to wait until the from . . . to observation is complete, which can take a while.

No matter how long, a from blank to bank construction usually works as a modifier. It's not hard to understand why an eight-, ten-, or twenty-word modifier can be cumbersome.

My best advice here is don't rely on this construction too much and be prepared to abandon it if it starts to get unwieldy. If your from or your to contains its own from or to, you're probably making a mess, as we saw previously in to participating in breast or ovarian cancer walks to raise research funds. If it requires semicolons to hold it all together, maybe you should recast the sentence.

Also, remember that there's no comma between the from and the to:

From soup to nuts.

That's easy to see in short from ... to phrases. But longer ones get confusing, inviting errant commas:

From soup made with the finest ingredients from age-old recipes, to chocolate-covered nuts we hand dip, to the moment when you get the check, you'll love our service.

The first two commas shouldn't be there. Remember: from blank to blank to blank is comma free even when your blanks are so long that they make you forget you were using this construction in the first place. Of course, that's probably a sign that your from ... to setup isn't cutting it.

Fatty prose can also happen because a writer is reluctant to make a bold statement:

Hawaiians have adopted a lifestyle that is decidedly more leisurely and tolerant than that of their fellows on the mainland.

This problem crops up a lot in my own writing. But editing others' writing is helping. I'm learning that it's worth the effort to look for bold alternatives:

The Hawaiian lifestyle is leisurely and tolerant.

Open up a copy of the New York Times or the Washington Post and you'll see lots of sentences like the latter example but almost none like the former. That's because top publications hate mealy-mouthed allusions and love solid, information-packed statements. I try to remember that.

Another example of fatty prose, again based on a real sentence by a professional writer:

One of the more remarkable aspects of the park is the fact that it has eight manicured gardens.

Compare that to the alternative:

The park has eight manicured gardens.

These six words do a better job of conveying the information than do the eighteen words in the first sentence. You get extra points if you noticed that, in the first example, the most notable information was crammed into a subordinate clause and used the fact that.

Don't underestimate the Reader. He can decide for himself whether having eight manicured gardens qualifies as remarkable. You're wasting his time by saying it's an aspect of the park. The Reader can connect one idea to the next without the help of in addition to. And he understands that the Hawaiian lifestyle is leisurely and tolerant is a generalization and subject to debate—no disclaimers required.

In other words, fatty insertions that can seem so meaningful when we're writing are often unnecessary at best and insufferable at worst. When in doubt, take them out.

Redundancies can be hard to spot. Vigilance is your best defense. Consider this sentence:

Flu viruses are known to be notoriously unpredictable.

We've seen how manner adverbs can create redundancies. But in this sentence, which I found in a Los Angeles Times article, the adverb isn't the problem.

Notoriously, by definition, means that something is well-known. Therefore, it's redundant with are known. But this adverb is pulling its weight and then some. It tells us in a single word that flu viruses are known for something. But because its definition also carries a negative connotation, notoriously adds extra information. The unpredictability of flu viruses isn't just famous, it's famously bad. That's why I suspect that, with a little more time or coffee, the copyeditor would have chopped out known to be, leaving just

Flu viruses are notoriously unpredictable.

Keep an eye out for these redundancies. Your ability to catch them will improve with practice.

Oh, and about those demons known as run-on sentences and comma splices: don't let the jargon intimidate you. You've already mastered far tougher concepts. Just note, for the record, a run-on sentence fails to properly link its clauses:

Elephants are large they eat foliage.

A comma splice, really just a type of run-on sentence, uses commas to link clauses that should stand on their own as sentences or at least be separated with a semicolon or conjunction:

Elephants are large, they eat foliage.

Both are easy to fix. Either make each clause a separate sentence, find some conjunction that can get the job done, or consider a semicolon:

Elephants are large. They eat foliage.

Elephants are large; they eat foliage.

Elephants are large, and they eat foliage.

Elephants are large because they eat foliage.

To fix flabby writing, watch out for words or little clusters of words that work well in speech but that don't translate well to the written word. Consider first whether you can cut them out altogether. If not, look for ways to streamline: In addition to the fact that tuition is affordable might be replaced with just also. Some fatty insertions can be cut altogether. For his part, as director for the Center for Computer Security, Brady emphasizes training says no less if you chop out for his part.

Also, watch out for sentences too cowardly to come out and say something or whose wording is just too convoluted. Remember that your goal is not fewer words, but economy of words.