It was the best of sentences, it was the worst of sentences - June Casagrande 2010

Grammar for writers

To know grammar, focus on the parts of speech and how phrases and clauses form sentences. All that stuff you've heard about how you supposedly can't use healthy to mean healthful and how it's supposedly wrong to say "Can I be excused?" in place of "May I be excused?"—that's not grammar. That's usage (much of it pure lies). Further, all that perplexing stuff like whether to write out numbers or use numerals and whether to put a comma before an and—that's called style. One doesn't know usage or style. Like the most skilled editors, you must look these things up.

For usage matters, have a trusted dictionary such as a recent American Heritage or Webster's New World or Merriam-Webster's Collegiate and a good usage guide such as Garner's Modern American Usage or Fowler's Modern English Usage and look up issues as they arise. For style matters, book authors and most magazine writers should have a copy of The Chicago Manual of Style. Journalists and public relations professionals should have The Associated Press Style-book. Organizations such as the Modern Language Association, the American Medical Association, and the American Psychological

Association have their own stylebooks. Usually, a professor or an employer will tell you if you need to follow one of these.

The nitpicky stuff—little matters of usage and style—can be looked up. But the stuff that will really help your writing is the mechanical, analytical stuff we call grammar. Throughout this book, we've touched on a lot of aspects of grammar. Here, now, is grammar long form.

Most grammar primers start with the parts of speech before moving on to phrases and clauses and then finally to sentence formation. But because we're most concerned with sentence formation, we'll reverse that order, looking first at sentence formation before moving on to phrase and clause structure and finally to the parts of speech, including how to form plurals of nouns and how to conjugate verbs.

Read or skim through this at least once. Then return to it whenever you need to better understand the mechanics of sentence writing.

Sentence Formation

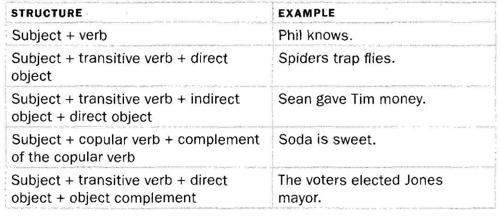

There are five basic structures for simple sentences, which are sentences that contain just one clause. On top of these five structures, optional elements called adverbials can be added. The following table shows the basic structures.

|

An indirect object is in essence a prepositional phrase that comes before the direct object and that, in its new position, no longer requires the preposition: |

Robbie made spaghetti for his mother. [His mother is the object of the preposition for.]

Robbie made his mother spaghetti. [His mother is an indirect object and is placed before the direct object spaghetti; the preposition for is omitted.]

Jake sends love letters to Mary. [Mary is the object of the preposition to.]

Jake sends Mary love letters. [Mary is an indirect object and is placed before the direct object love letters; the preposition to is omitted.]

A complement of a copular verb is not the same as an object of a transitive verb. An object receives the action of the verb, but the complement of a copular verb refers back to the subject:

Anna seems nice.

Boys become men.

Coffee smells good.

An object of a transitive verb can have its own modifying complement. This is called an object complement (or an object predicative). The object complement can be an adjective phrase or a noun phrase. It describes the object or tells what the object has become:

Spinach makes Pete strong. [The adjective strong is a complement of the object Pete.]

Spinach makes Pete a man. [The noun phrase a man is a complement of the object Pete.]

A sentence with more than one independent clause is a compound sentence. In a compound sentence, the clauses can be coordinated with a coordinating conjunction. Coordinate clauses have equal grammatical status.

A sentence that contains at least one subordinate clause is called a complex sentence:

Birds make nests and they sing, [compound sentence containing two coordinated clauses of equal grammatical weight]

Because Andy is hungry, he eats, [complex sentence containing a subordinate clause and a main clause]

Subjects and objects can be phrases or whole clauses:

The dog sees that you are scared [The subject is the noun phrase the dog; the object of the verb sees is the subordinate clause that you are scared.]

To know him is to love him [To know is an infinitive clause functioning as the subject of the verb is; to love is an infinitive clause functioning as a complement of the verb.]

ADVERBIALS

Other sentence elements, called adverbials, can be added on to the basic sentence structures. An adverbial can be an adverb, a prepositional phrase, a clause, or a noun phrase. Though an adverbial may contain crucial information, it is not crucial to the sentence's core structure in the way that subjects, verbs, objects, and complements are.

For example, in The van followed Harry to the park, remove the adverbial (the prepositional phrase to the park) and you retain a grammatical sentence: The van followed Harry. Like adverbs, adverbials can answer the questions when, where, in what manner, and to what degree, or they can modify whole sentences. Or, like adjectives, they can modify nouns. The following examples illustrate adverbials:

The van followed Harry to the park, [prepositional phrase answering the question where]

The van followed Harry this afternoon, [noun phrase answering the question when]

In addition, the van followed Harry, [prepositional phrase connecting the sentence to a prior thought]

The van discreetly followed Harry, [adverb modifying the verb followed]

The van followed Harry where he walked, [whole clause answering the question where]

NEGATION

Sentences are said to be positive or negative. Sentences can be made negative by inserting not after the operator, which is usually the first word in the verb phrase but can also be a form of do, which is called a dummy operator and must often be inserted, as well:

The peaches are ripe, [positive] The peaches are not ripe, [negative]

William has worked hard, [positive]

William has not worked hard, [negative; not inserted after

auxiliary has but before past participle worked]

Your daughters go to college, [positive]

Your daughters do not go to college, [negative; not inserted

after dummy operator do]

QUESTIONS

Declarative sentences (statements) can be made into interrogatives (questions) by switching the positions of the subject and the operator, which is the first word in the verb phrase or the dummy operator do:

Dolphins are clever, [declarative]

Are dolphins clever? [interrogative formed through inversion]

Storytelling has been part of our culture for centuries, [declarative]

Has storytelling been part of our culture for centuries? [interrogative formed through inversion]

You like cake, [declarative; could also be expressed with a dummy operator as You do like cake] Do you like cake? [interrogative formed with dummy operator do]

In spoken English, sentences can also be made into questions through intonation. In writing, this can be represented as a positive statement followed by a question mark: That's what you're wearing? You'll he there on time?

VARIATIONS ON BASIC SENTENCE STRUCTURES There are many possible variations on the basic sentence structures. These alternatives include sentence fragments, cleft sentences, existential sentences, and other structures in which sentence elements have been moved. These all mix up the order of the standard form. Think of them as creative devices at your disposal. A sentence fragment is an incomplete sentence:

That's what he wanted. Money.

Incomplete sentences like Money are completely acceptable in fiction and nonfiction—especially in informal contexts.

Cleft sentences use it + is or was and a relative pronoun like that or who to add emphasis. So,

Leo saved the day.

made into a cleft sentence becomes It was Leo who saved the day.

Existential sentences put there is or there are at the head of a sentence for emphasis:

Aliens are in the building.

becomes

There are aliens in the building.

Other variations include

• Left dislocation, in which the subject gets bumped to the left and a repetitive pronoun takes its place: Cars, they're not what they used to he.

• Right dislocation, in which the pronoun duplicates the work of a subject and the subject is bumped to the right: They have a lot of money, Carol and Bill.

• Other rearrangements, such as a prepositional phrase moved to the front of a sentence: To the mall we will go.

Phrases

A phrase is a unit of one or more words that function as either a noun, a verb, an adverb, an adjective, or a prepositional phrase. Phrases can contain phrases within them:

Many dogs regularly enjoy the public park on Sundays.

many dogs [noun phrase]

regularly [adverb phrase]

enjoy [verb phrase]

the public park [noun phrase]

public [adjective phrase within noun phrase]

on Sundays [prepositional phrase]

Clauses

A clause is a unit that usually contains a subject and a verb. A single clause can be a complete sentence:

Jeeves slept.

Infinitives and units called participial clauses or participial phrases are also understood as clauses, even though they don't contain an explicit subject:

Perry never learned to dance.

Ben mastered fencing.

Clauses are said to be either finite or nonfinite. Finite means they contain a conjugated verb expressing a time element. Nonfinite means that the verb does not convey the time of the action. Infinitive clauses like to dance, in the example, are nonfinite.

Parts of Speech

Many words can function as more than one part of speech.

NOUNS

A noun is a person, place, or thing. This includes intangible things. Thrift is a noun. Wrongness is a noun. A noun (or noun phrase) can be

• a subject: Milk is delicious.

• an object of a verb: I drink milk.

• an object of a preposition: I serve cookies with milk.

• a modifier: Fill that milk bucket.

• a subject predicative: This substance is milk.

• an object predicative: I call this substance milk.

A subject performs the action of a verb.

A subject predicative is the complement of a copular verb, usually to be.

An object predicative is the complement of the object of a transitive verb. An object predicative can be a noun (The sheriff made him a deputy) or an adjective (The sheriff made him angry).

The plural of most nouns is formed by adding s: buildings, papers, ideas. Nouns ending in y often form their plurals by replacing y with ies. Words ending in j often form their plurals by adding es: bosses. For irregular plurals like children, men, deer, data, and so on, consult a dictionary.

Possessive nouns are formed as follows:

• singular and plural nouns not ending in s—add an apostrophe and an s: The cat's tail. The children's mom.

• plural nouns ending in s—add only an apostrophe: The dogs' tails. The kids' dad.

• singular nouns (generic nouns and proper names) ending in s—Style guides disagree on whether these take an apostrophe and an s or just an apostrophe. Per The Chicago Manual of Style, it's Charles's hat. Per The Associated Press Stylebook, it's Charles' hat. Further, style guides contain many exceptions and special rules. Consult the appropriate style guide or choose one of two basic methods and use it consistently. The basic methods are to either always add an apostrophe and an s after a singular word ending in .s or just add the apostrophe without an s.

PRONOUNS

Pronouns are small words that stand in for nouns. They come in different types:

• personal pronouns, subject form: I, you, he, she, it, we, they

• personal pronouns, object form: me,you, him, her, it, us, them

• indefinite pronouns: anybody, somebody, anything, everything, none, neither, anyone, someone, each, nothing, both, few, and others

• possessive pronouns: mine, yours, his, hers, its, ours, theirs

• relative pronouns: that, which, who, whom

• interrogative pronouns: what, which, who, whom, whose, whatever, whichever, whoever, whomever, whosever

• demonstrative pronouns: this, that, these, those

• reflexive pronouns: myself, yourself, yourselves, himself, herself, itself, ourselves, themselves (These words refer back to a subject—He saw himself in the mirror, or they are used for emphasis—I, myself, don't like the tropics.)

• other pronouns: the existential there, several uses of it, the substitute one

The existential there is used to emphasize new information. It moves to the subject position in the sentence. The noun phrase that otherwise would have occupied the subject position is called the notional subject: Clowns were juggling (clowns = subject). There were clowns juggling (existential there = grammatical subject, clowns = notional subject).

It can fill several unique roles. It can be used to balance a sentence that would otherwise start with a clause as the subject: That you got a job is good news versus It is good news that you got a job. This is sometimes called the "anticipatory it." Or, instead of referring to a noun, it can refer to a previous sentence or idea: Leo is going back to school. It's the right choice for him. Or it can create a cleft sentence, a sentence that is split in order to emphasize a particular part of it: It is the storm that caused the power outage, instead of The storm caused the power outage. Or it can stand in for a subject or object in a sentence where one is needed, especially in references to weather or time: It is noon. It is raining.

One, in formal uses, can stand in as a nonspecific alternative to a noun or pronoun: One can visit the gift shop. In informal contexts, you is often preferred: You should check with your doctor.

DETERMINERS

Determiners introduce noun phrases and can provide information about possession, definiteness, specificity, or quantity:

• possessive determiners: my, your, his, her, its, our, their

• articles: a, an (indefinite articles); the (definite article)

• demonstratives: this, that, these, those

• wh- determiners: which, what, whose, whatever, whichever, and so on

• quantifiers and numbers: all, both, few, many, several, some, every, each, any, no, one, five, seventy-two, and so on

Many determiners are also pronouns. Most possessive determiners are similar to their corresponding possessive pronouns: her is a possessive determiner, while hers is a possessive pronoun. The possessive determiners his and its are identical to their corresponding possessive pronouns. The function in the sentence determines the part of speech. In The red Toyota is his car, his is a determiner because it's introducing the noun phrase car. In The red Toyota is his, his is a pronoun because it's functioning as a noun phrase. In The company made this pen, this is a determiner. In The company made this, it's a pronoun because it stands in place of a noun phrase.

VERBS

Verbs convey action and states of being. Think of four main types:

• intransitive—does not take a direct object: Jeremy talks.

• transitive—takes a direct object: Jeremy enjoys TV.

• copular or linking—refers back to the subject -.Jeremy is nice.

• auxiliary—a helping verb that works with past or present participles, usually forms of have, be, or do: Jeremy has eaten dinner. Jeremy is resting.

• modal auxiliaries—a special set that includes can, may, might, could, must, should, will, shall, ought to, and would. Modal auxiliaries address factuality: It might rain. Or they address human control or permission: You may be excused.

Many verbs have both transitive and intransitive forms: Jeremy knows (intransitive) but Jeremy knows math (transitive); Stephanie walks (intransitive) but Stephanie walks the dog (transitive).

Copular verbs convey being, seeming, or the senses: be, appear, act, seem, smell, taste, feel, sound. Unlike a transitive verb, which takes an object (Dan eats cheese), a copular verb takes something called a complement (Dan seems dishonest). Where a transitive or intransitive verb would take an adverb (Nancy works happily), a copular verb takes an adjective (Nancy is happy). Some verbs can have both copular and noncopular forms, depending on meaning: Neil acts badly (not copular) means Neil is an unskilled thespian. Neil acts bad (copular) means he acts as though he is bad. In Fido smells meat, smells is a transitive verb with the object meat. But in Fido smells terrible, smells is a copular verb whose complement, terrible, refers back to the subject. In the common expression I feel bad, the verb feel is copular, which is why it takes an adjective and not an adverb as its complement.

Verbals are verb forms that work as other parts of speech. They are

• gerunds—the -ing form of a verb working as a noun: Dancing is good exercise.

• participles—usually an -ing, -ed, or -en form. When a participle works as a modifier instead of as part of a verb, it qualifies as a verbal: A man covered with bee stings came into the hospital. A child skipping to school is probably happy.

• infinitives—a verb form introduced by the infinitival to: to run, to know, to become. Infinitives can act as subjects: To know him is to love him. But infinitives are also said to act as adjectives by modifying nouns (There are many ways to travel) and as adverbs by modifying adjectives (I am happy to help).

Verbs can be seen in terms of tense, aspect, mood, modality, and voice.

Tense indicates either present, past, or future time.

Present-tense verb conjugations are simple in English, with most verbs changing form only for the third-person singular:

I walk [first-person singular]

You walk [second-person singular and plural]

He/she/it walks [third-person singular]

We walk [first-person plural]

They walk [third-person plural]

Most words create the third-person singular present tense by adding s. Some words also add an e: I go, you go, he goes. I pass, you pass, she passes. Verbs that end in a consonant plus a y change the y to ie before adding the s: I worry, you worry, he worries. To be is completely irregular: I am, you are, he is.

Subject-verb agreement describes the use of the correct verb form to correspond with the subject. Failure to use the correct verb conjugation is considered ungrammatical:

I am [grammatical because first-person singular subject agrees with first-person singular verb]

I is [ungrammatical because first-person singular subject does not agree with third-person singular verb]

A past-tense verb can be a simple past-tense form or can use a past participle with an auxiliary:

Yesterday I walked, [simple past tense]

In the past I have walked, [auxiliary have + past participle walked]

Regular verbs add -ed to form both the past tense and the past participle:

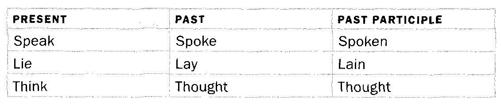

Irregular verbs can take varying forms: |

|

Most dictionaries list past tense and past participles of irregular verbs in bold right after the main word entry: go, went, gone. Some dictionaries also list these forms for regular verbs. If a dictionary offers no past or past participle forms for a verb, you can assume that the verb is regular and follows the same form as walk.

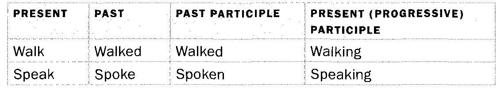

The present participle, also called the progressive participle, is the -ing form, which is used with one or more auxiliaries.

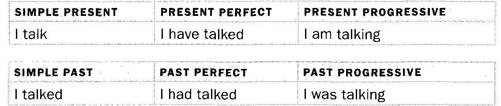

Aspect tells you whether an action is completed or whether it is or was ongoing. The perfect aspect uses a form of the auxiliary have plus a past participle: He has spoken. We have spoken. The progressive aspect uses a form of to be plus a present participle: He is speaking. We are speaking. Some sources count simple as an aspect.

Mood is categorized into three types: indicative, imperative, and subjunctive:

• Indicative is the most common mood. Sentences in the indicative are usually statements, also called declaratives: Sal washes the dishes. Interrogatives (questions) and exclamatives

(exclamations) are also categorized as indicatives, with their verbs behaving similarly to the verbs in statements.

• The imperative mood is used for commands: Wash the dishes. Imperatives are considered complete sentences. The subject is implied. It is you: [You] Wash the dishes.

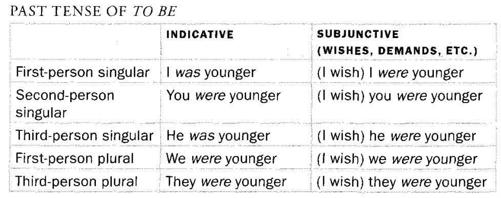

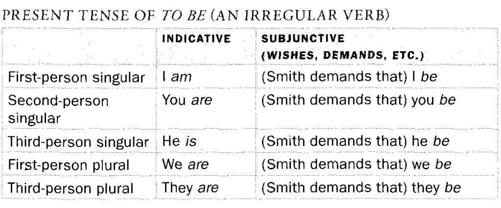

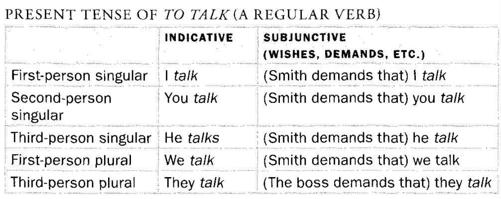

• The subjunctive mood indicates statements contrary to fact (such as wishes and suppositions), propositions and suggestions, and commands, demands, and statements of necessity. Some uses of the subjunctive are dead or dying. In modern usage, it's most useful to think of the subjunctive as follows: In the past tense, the subjunctive applies only to the verb to be, and it is conjugated as were. The form differs from the indicative only for the first-person singular and the third-person singular.

In the present tense, the subjunctive can apply to any verb. To form the present subjunctive, replace the conjugated form with the base form of the verb. (Think of the base form as the infinitive without to)

For all these except the third-person singular, the subjunctive form is identical to the indicative form.

Modality is most helpful for understanding modal auxiliary verbs. Modal auxiliaries such as can, may, might, could, must, should, will, shall, ought to, and would deal with factuality or human control: William can help uses the modal auxiliary can to address human control. That coffee might be decaf uses the modal auxiliary might to address factuality.

Voice is either active or passive.

Active voice puts the subject of a transitive verb as the grammatical subject of the sentence: Sam throws the ball.

Passive voice puts the intended object of a transitive verb as the grammatical subject of the sentence: The ball is thrown by Sam.

PREPOSITIONS

Definitions of the class of words known as prepositions are vague and unsatisfying. Most say something like "Prepositions link nouns, pronouns, and phrases to other words in a sentence." Some people note that many prepositions—above, on, in, around, and so on—show physical proximity.

The best way to understand prepositions is to look at how they form prepositional phrases. A prepositional phrase is a preposition and its object. Though this fails to define prepositions, it can help you understand and identify them. Here are some of the most common prepositions: to, with, in, on, from, at, into, after, out, below, until, around, since, beneath, above, before, as, among, against, between, below, and over.

Some words can function as either prepositions or conjunctions. They include after, as, before, since, and until. For example, before is a preposition in I'll have my homework done before bedtime because it introduces a noun. That noun, bedtime, is its object. But before is a conjunction in I'll have my homework done before I go to bed because before introduces a whole clause, which is a job for a conjunction.

The object of a preposition is a noun phrase, which can be a noun or a pronoun with or without determiners and modifiers:

Megan studied with Joe.

The dogs are at the grassiest park in town.

The awning hangs above the door. The butter is on the wooden table. Mark gave the money to them.

The object of a preposition is said to be in object form. So any pronoun paired this way with a preposition should be an object pronoun and not a subject pronoun:

Megan studied with him [not] Megan studied with he

Mark gave the money to them [not] Mark gave the money to they

This is between us [not] This is between we

Don't throw that at me [not] Don't throw that at I

Talk to him or me [not] Talk to he or I

This is between you and me [not] This is between you and I

Prepositional phrases can be understood as modifiers or adverbials. Prepositional phrases can modify nouns: the man with the red hat. They can modify actions: She sings with enthusiasm. Prepositional phrases can also function at the sentence level, answering questions like when and where. He will meet you at the corner. In the morning, breakfast will be served. Or they can modify whole sentences: In Addition, note the location of the exit.

IT WAS THE BEST OF SENTENCES, IT WAS THE WORST OF SENTENCES ADVERBS

Adverbs answer the questions

• when? I'll be there soon.

• where? Bring the laundry inside.

• in what manner? Belle and Stan argued bitterly.

• how much or how often? Bruno is extremely busy. He is frequently overwhelmed.

Adverbs can also give commentary on whole sentences. These are called sentence adverbs: Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn. Adverbs can also create a link to a previous sentence. These are called conjunctive adverbs: However, the parade was a success.

Adverbs can modify verbs (Mark whistles happily), adjectives (Betty is extremely tall), other adverbs (Mark whistles extremely happily), or whole sentences (Tragically, the crops didn't grow).

There also exist things called adverbials, which may or may not be adverbs:

Additionally, students learn engine repair.

In addition, students learn engine repair.

CONJUNCTIONS

Conjunctions connect words, phrases, and clauses. They can be divided into coordinators and subordinators.

Coordinators link units of equal grammatical status. The primary coordinating conjunctions are and, but, and or. Also sometimes functioning as coordinating conjunctions are for, nor, so, and yet. Some correlative expressions are also understood as coordinators.

They include either... or, neither. . . nor, both . . . and, not. . . but, and not only . . . but also.

Heather likes coffee and tea. [coordinator and linking noun objects]

Todd likes coffee but not tea. [coordinator but linking noun objects]

Heather and Todd like coffee, [coordinator and linking noun subjects]

I must go to bed now or I will oversleep tomorrow, [coordinator or linking grammatically equal clauses]

Eat carrots so your eyes stay healthy, [coordinator so linking grammatically equal clauses]

Eat up, for tomorrow we shall fast, [coordinator for linking grammatically equal clauses]

He doesn't take the subway, nor does he take a cab. [coordinator nor linking grammatically equal clauses]

Either you stay or you go. [correlative expression either. . . or linking grammatically equal clauses]

Both Matt and Sam will be there, [correlative expression both . . . and linking noun subjects]

Subordinating conjunctions are a larger group. They include because, if, while, although, though, until, till, as, since, when, than, before, and why and longer expressions such as even though, as soon as, as much as, assuming that, and even if. Certain subordinating conjunctions that convey time, including before, since, and until, are also used as prepositions.

Subordinating conjunctions introduce subordinate clauses, also called dependent clauses. Subordinate clauses cannot stand alone as sentences:

The room was redecorated, [complete sentence]

Before the room was redecorated . . . [subordinate clause that is not a complete sentence]