It was the best of sentences, it was the worst of sentences - June Casagrande 2010

Size matters: Short versus long sentences

Here's a great opening sentence for a magazine article:

Alec Baldwin has the unbending, straight-armed gait of someone trying to prevent clothes from rubbing against sunburned skin.

This sentence is not just interesting and visual, it's very effective at setting the tone for the article. You can tell right away that the writer has a unique take on Baldwin. With just one sentence, the writer has evoked that riveted sensation you get when you can't look away from a four-car pileup on the side of the freeway. It's clear that this will not be the typical fawning feature article. It will not read as though it were pitched by Baldwin's publicist. There's no doubt you're in for a good read.

But what if the writer, in the middle of this sentence, decided that there were some other bits of information that just couldn't wait till sentence two? What if she said, "Ah, crud. I had a good sentence here but if I don't squeeze in something about Baldwin's work and state of mind, I may never get another opportunity"?

You might end up with something like this:

Alec Baldwin, who stars in 30 Rock, the NBC sitcom that has revived his career and done nothing to lift his spirits, has the unbending, straight-armed gait of someone trying to prevent clothes from rubbing against sunburned skin.

This is a textbook example of how longer sentences can sabotage writing. The inserted information is an interruption. When you look at the grammar, you see it's a clunky interruption at that. The writer has inserted a relative clause, who stars in 30 Rock, which is then restated as an appositive, the NBC sitcom, which in turn is modified by not just another relative clause but a double-duty relative clause: that has revived his career and done nothing to lift his spirits. We'll talk about those terms later. But for now the important thing is that all this bulky stuff comes between the subject and the main verb, has. You have to trudge through all that stuff just to get to the main point. Pretty much any freshman English teacher or Palookaville Post copy editor will tell you this is the wrong call.

There's just one problem. The longer version of the Alec Baldwin sentence, not the shorter one, was the opening sentence of an article in one of the most respected magazines in the country: the New Yorker.

A lot of people will tell you that the longer sentence is always the lesser sentence. Some even say long sentences are an out-and-out no-no. But it's not that simple.

Personally, I have a strong bias in favor of short sentences. I suspect that the New Yorker's not-infrequent use of longer, clunkier forms is a deliberate flouting of conventional wisdom—a sort of "We don't take orders from freshman comp teachers because we're the New Yorker, dammit" approach. But I could be wrong. Plenty of people in the world would prefer the longer sentence. The writer and/or editors of the New Yorker may be among them.

In fact, you could argue that the second sentence carries some unique benefits. It shakes up the Reader by defying conventional form. As such, it has an ability to command attention that the shorter version does not. Further, some of the inserted stuff actually bolsters the point of the sentence. In particular, the fact that Baldwin's successful show has done nothing to lift his spirits is both relevant and juicy. It gives further insight into why this guy might walk around as though he's trying not to rub a sunburn. And though we could find plenty wrong with the real New Yorker sentence, it's actually quite skillful and effective.

Now compare two more long sentences:

After being rebuffed as the next head football coach at Boston College after Jeff Jagodzinski was fired two weeks ago and after not being hired at the University of Massachusetts after Don Brown left to become the defensive coordinator at the University of Maryland, Boston College assistant head coach and offensive line coach Jack Bicknell Jr. is moving to the NFL, as an assistant offensive line coach of the New York Giants, according to several sources close to the program.

and

The play—for which Briony had designed the posters, programs and tickets, constructed the sales booth out of a folding screen tipped on its side, and lined the collection box in red crepe paper—was written by her in a two-day tempest of composition, causing her to miss a breakfast and a lunch.

The first one—the opening sentence of a Boston Globe sports-writer's blog—reads as though the writer couldn't wrap his head around the sequence of events. The second sentence reads as though the writer had an intimate knowledge of a complex series of events and all the sights and smells and sounds and emotions attached to l hem. So you won't be surprised to learn that the second one is the opening sentence of Ian McEwan's prizewinning novel Atonement.

Though it's leaps and bounds better than the sportswriter's sentence, I'm not a big fan of McEwan's sentence. To me, it's unnecessarily busy. I don't like the passive was written by her. I don't like the stiff and awkward for which Briony or how it sort of turns the sentence upside down. And the copy editor in me is almost offended by McEwan's choice to squeeze a whopping thirty-two words between the subject and the verb. But if I were the copy editor, I wouldn't change a word. I can't see any way to restructure it that doesn't take away from the author's voice and his style and the effect he's working to create—elements that should never be discounted or sanitized into oblivion to accommodate sentence-length sticklers or by-the-book copy editors. It seems that the very things I don't like about the sentence are things McEwan was trying to convey: the sentence is tempest-like. If he was trying to create a sense of frenetic passion-driven activity, mission accomplished. It's not my cup of tea. I'm more a fan of Kurt Vonnegut's one-word paragraph, "Listen." But that's just me.

Compare two more examples and you'll see why, in general, I'm biased toward shorter sentences:

I killed him even though I didn't want to because he gave me no choice.

I killed him. I didn't want to. He gave me no choice.

I believe that modern sensibilities are more attuned to short sentences. Media culture is partly responsible. Think about it. We spend countless hours listening to thirty-second TV commercials that contain six, eight, ten sentences each. But we know that most of the words are just filler. Each commercial has only one central message that boils down into one sentence: "Windex doesn't leave streaks." "Drive a Mustang and you'll be popular with the ladies." "If you really love your kids, you'll buy Purell hand sanitizer." The central message is supplemented with extra sentences used to hammer home the same point. As a culture, we're becoming ever more inclined to tune out fluff. Stripped-down-bare information is an anomaly that can command our attention and our respect.

Another problem with our longer sentence: extra words can have a diluting effect. In I killed him even though I didn't want to because he gave me no choice, the linking terms even though and because seem mealymouthed. It's like the writer is scrambling to explain herself, speaking from a weak, pleading position. It's almost ironic how the facts stand stronger when they stand alone, unmitigated by the writer's urge to overexplain: I killed him. I didn't want to. He gave me no choice.

Still, anyone who tells you straight out that short sentences are superior is either overlooking or discounting some of the most respected writers of all time.

So, then, what's the verdict? Are short sentences better or not?

Allow me to end this debate once and for all. Here's how you should look at it: Brevity is a tool. It's a very powerful tool. You don't have to use it. But you have to know how. If you're going to use long sentences, it should be by choice, not due to bumbling ineptitude. Every long sentence can be broken up into shorter ones, and if you don't know how—if you don't see within your long sentences groupings of simple, clear ideas—it will show.

You should master the art of the short sentence, even if you prefer longer ones. All you have to do is start looking at every sentence as a group of phrases and clauses. See in each sentence how every bit of information could carry a sentence of its own. Then you'll have the power to decide exactly how to organize your information.

Let's practice:

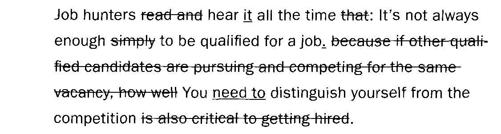

Job hunters read and hear all the time that it's not always enough simply to be qualified for a job because, if other qualified candidates are pursuing and competing for the same vacancy, how well you distinguish yourself from the competition is also critical to getting hired.

This sentence did not appear in print. It's the result of my playing Dr. Frankenstein with another writer's words, which I have disguised. (You're welcome, other writer.) But trust me when I tell you that the original wasn't much better.

Now let's look at the clauses in this sentence: job hunters read and [job hunters] hear it's [not always enough]

Remember that it's means it and is, which together form a whole clause.

to be [qualified]

Remember we said that infinitives can also be categorized as clauses.

other qualified candidates are pursuing and [other qualified candidates are] competing you distinguish

[this distinguishing] is [critical] to getting [hired]

The last one is another nonfinite clause.

As you can see, clauses are not all ideas unto themselves. They can do different jobs in a sentence. For example, how you distinguish yourself has at its heart the clause you distinguish. But it's not an action in our sentence. It's working with the how to function as a subject of a verb: How you distinguish yourself is critical. The main verb of this sentence is is. The subject is the whole how clause. Here are some other examples of how a clause can work like a noun to serve as a subject: What I want is a soda. How you look is important. Whatever you do is okay with me. That you love me is all I need to know. In all these sentences, the main verb is is, and in all these sentences, the subject—the doer of the action—is a whole clause.

Now let's separate some of the bits of information in this sentence. For this breakdown, we're not looking for clauses but for all the individual ideas in the sentence:

• There is something that job hunters frequently hear.

• It is also something they frequently read.

• Being qualified for a job isn't always enough to land a job.

• Other candidates may be pursuing the same vacancy.

• Other candidates may be competing for the same vacancy.

• Distinguishing yourself is critical to getting hired.

Do you see unnecessary information in here? Is it really important to note that job hunters hear and read this? Why stop there? Why not say they hear and read and sniff out and deduce and realize and innately understand and feel with their fingertips while reading Braille and any other activity that conveys information to your brain? No doubt, the writer believed she'd be remiss if she overlooked the fact that job seekers both read and hear it. My advice: Be remiss. It's okay to just say, "They hear it all the time," as long as your Reader understands. There's no need to include a laundry list of all the ways that a job seeker might encounter the information.

Another bit of unnecessary information in our sentence is that business about other candidates pursuing and competing for the same vacancy. Even more than the see and read stuff, this is a major duh. Pursuing the same vacancy means competing. Also, how is competing for the same job different from competing for the job? The word compete already suggests that it's the same job. Adding the word same creates a redundancy on top of the redundancy pursuing and competing for.

So, what would you do with our original Frankensentence? The possibilities are infinite. Here, slightly disguised, is what I did:

Job hunters hear it all the time: It's not always enough to be qualified for a job. You need to distinguish yourself from the competition.

Here's how it would look as a copyedited version of our original sentence, with strikethroughs marking deletions and underscore showing insertions:

We brazenly omitted read and.

We changed the object of the verb hear. In the original, the thing being heard was a whole relative clause: that it's not always enough . . . We replaced this long clause with the simple pronoun it, then inserted a colon to tell the Reader that we will promptly explain what it is.

We lost all mention of other qualified candidates who are competing for and pursuing. That's all summed up quite nicely by the competition.

We deleted the whole clause that began because if other qualified candidates . . . The Reader already gets that.

We found the action in our how clause and made it more meaningful by setting it up in a sentence with the main clause you need.

Also, we got rid of the fatty adverb simply.

Now let's look at a sentence whose disastrousness is a little more straightforward:

Because Paul had wanted to get into doing masonry work since he was in college, due in part to the fact that, as a college student, he had always wished he could work with his hands, which gave him a satisfaction he had never known before and which he discovered only in his third year of school when he took metal shop before eventually taking a masonry course at the Home Depot, he finally decided it was time for him to take the plunge.

Unlike our last sentence, this one contains no tricky uses of clauses as subjects or self-conscious redundancies. It's all good, clear, straightforward information that, unfortunately, has been shoved into the writer's mental Cuisinart. But it's easy to get a handle on it, and your experience with subordinating conjunctions will make this task even easier.

Let's break up the sentence without worrying about flow or organization of information or logic or voice. Just examine some of the basic ideas within and how they might boil down to their own sentences:

• Paul had wanted to do masonry work since he was in college.

• As a college student, he had always wished he could work with his hands.

• It gave him a satisfaction he had never known before.

• He discovered this only in his third year of school.

• He took metal shop.

• Then he took a masonry course at the Home Depot.

• He finally decided it was time to take the plunge.

This breakdown does not give us our end result. For one thing, the writer had used subordinators such as before and when to make sense of nonchronological information. When we take out those conjunctions, a confusing series of events becomes downright nonsensical. But now we can see that the writer was trying too hard to cram in background information. Also, by breaking this up, we now have neat and distinct ideas that we can move around like dominoes. We can put them into any order we like. Here's the same information put into more logical order:

• Paul wanted to learn how to do masonry work.

• He had wanted this since he was in college.

• In his third year of college, he had taken metal shop.

• Then he took a masonry class at the Home Depot.

• Working with his hands gave him a satisfaction he had never known before.

• He finally decided it was time to take the plunge.

This still needs work. For example, we haven't said when he finally decided it was time to take the plunge. In our original sentence, it was clearer that the when was now. We lost that in the rewrite. But now we have our information in a more logical—if not chronological— order. Cause-and-effect relationships have begun to reveal themselves. So we're closer to a finished product. And now we can make further choices as to how we want to structure our information and whether to add or omit facts:

Working with his hands gave Paul a satisfaction he had never known before. He discovered this passion in college when he took metal shop. As soon as the semester ended, he signed up for a masonry class at the Home Depot. Now, at age fifty-one, he could no longer deny that this was the only work he had ever wanted to do. It was time, he decided, to take the plunge.

Another possibility:

Since college, Paul had wanted to work with his hands. A metal shop class in his third year inspired him to take a masonry class at the Home Depot. Working with his hands gave him a satisfaction he had never known. Finally, thirty years later, he decided it was time to leave the accounting field and pursue his dream.

By the way, don't feel bad if your sentences come out long and rambling at first. For many people, that's just part of the writing process. I write some major stinkers myself. It doesn't mean you're a bad writer or you lack talent. It just means that your process for writing good sentences involves putting your messy ideas on paper before cleaning them up. I suppose some people organize all their thoughts in their head before putting them on paper. Kudos to them. But it doesn't mean they're necessarily better writers. There's nothing wrong with writing sentences that come out clunky at first, as long as you can reread your own writing and see where revisions could make your sentences better.

Let's analyze another sentence. This one's a little trickier than the last. It's based on a real but unpublished sentence by a professional writer:

In addition to assisting her with the practical aspects of returning to school (such as writing a successful application essay and obtaining financial aid), Elizabeth, the center's advisor, who was always quick with a smile and a word of encouragement, helped Rona address her feelings of self-doubt, uncertainty, and apprehensiveness.

Start by trying to isolate the main clause. Can you find it? The main action of the sentence is helped and the person doing the helping— the subject—is Elizabeth. But the writer isn't exactly helping the Reader by cramming fifteen words between the subject and the verb. Yes, it's perfectly okay to separate a subject and its verb, but only when it works. Here, it just adds too many words into an already busy sentence.

And how about that introductory phrase that begins In addition to? That's a whole lot of information to get into a single breath. By the way, this is called an adverbial. We'll talk more about adverbs and adverbials in chapter 7. What matters here is, does all that information really fit in our sentence? No.

What to do, then, about this monstrous sentence? Often, the simplest solution is to just drop all the conjunctions and fillers and parentheses and other connecting devices and make simple sentences out of what's left. That is, isolate the clauses and/or distinct ideas and form them into individual sentences:

Elizabeth assisted Rona with the practical aspects of returning to school. She helped Rona write an application essay and apply for financial aid. Elizabeth was the center's advisor. She was always quick with a smile or a word of encouragement. She helped Rona address her feelings of self-doubt, uncertainty, and apprehensiveness.

Now we can see that the very essence of our bad sentence was actually a cluster of clear, simple ideas that can be expressed clearly and simply. The beauty of boiling it down this way is that now you can make more choices. You can rearrange the facts and choose which ones to emphasize. For example, I'd move up and shorten the part about Elizabeth's job title. You can change verb tenses to contrast the historical with the here-and-now, weighing the pros of choosing Elizabeth had assisted over the simpler Elizabeth assisted. (We'll talk more about these verb tenses in chapter 12.) You can insert other words to show things like causality: Because she was always quick with a smile or a word of encouragement, Elizabeth helped Rona with her feelings of self doubt, uncertainty, and apprehensiveness. You can question whether uncertainty and self-doubt are redundant or whether the word uncertainty indeed conveys something distinct from self-doubt. You can decide whether some information, especially the stuff that had been in parentheses, should be folded into another sentence in order to downplay it a bit.

Personally, I'd go for a clear, no-frills rewrite like this:

Elizabeth, the center's advisor, assisted Rona with the practical aspects of returning to school. She helped Rona write an application essay and apply for financial aid. Always

quick with a smile or a word of encouragement, Elizabeth also helped Rona address her feelings of self-doubt and apprehensiveness.

There's no single right answer. And again, every rewrite contains the danger of lost meaning or lost information or even the possibility you'll make the sentence factually incorrect. So while reworking for clarity, the writer must always keep a tight rein on accuracy and meaning.

But what if you don't want clarity? What if you want a big mess—a sentence that conveys not a series of simple, distinct ideas, but instead a mood, a vibe, a vague sense of things not unlike mist. Then you could end up with a sentence like this:

At the hour he'd always choose when the shadows were long and the ancient road was shaped before him in the rose and canted light like a dream of the past where the painted ponies and the riders of that lost nation came down out of the north with their faces chalked and their long hair plaited and each armed for war which was their life and the women and children and women with children at their breasts all of them pledged in blood and redeemable in blood only.

Would that make you a bad writer? Would that make you someone who doesn't grasp the power of short sentences or even complete sentences, which this is not? On the contrary, writing that sentence would make you Cormac McCarthy—a Pulitzer winner and, to some, one of the greatest writers of our time. That would also make you an exception to my personal preference for short sentences. I love that McCarthy sentence. It's almost impossible to defend it out of its context in All the Pretty Horses. But in context, I feel that it works. It's a mess, but it's supposed to be a mess. The whole is not the sum of its parts. It's something different—less a collection of events and facts and more a mystical, elusive, faraway sense of tragically beautiful things that were and will never be again.

Placement counts, too. One of my biggest problems with the sentence from Atonement is that it's the very first sentence of the book. Had the above excerpt from All the Pretty Horses been the first sentence in that book, I would never have read the second. But it wasn't. It came as seasoning in a story already well under way, built on a solid foundation that contained lots of simple and straightforward sentences. That made all the difference.

Why do I get to say so? What gives me the right? True, I'm not the world's leading authority on good versus bad long sentences. I'm someone even more important than that. I'm McCarthy's Reader. I have absolute power to say whether his sentence worked for me. And it did. Just as he gambled it would.

If it helps, divide writing into two categories: craft and art. If you're plying the craft of writing, aim to make many of your sentences short. Note the word many. Even the most hard-nosed short-sentence advocate will agree that too many short sentences strung together can be downright droning. Mixing short sentences with long ones can make your writing more rhythmically pleasing and therefore more Reader friendly. Writers of business letters, press releases, nonfiction books, genre novels—anyone who is more interested in content than form—usually fall into this writing-as-craft category in which short sentences are probably a virtue.

If, on the other hand, you're shooting for art, all bets are off. Art and beauty, more so than clarity and expediency, are in the eye of the beholder. If you think you can write an eighty-nine-word sentence that creates for your Reader a better experience than would a ten- or fifteen-word sentence, do. Go nuts. But remember, short sentences can be art, too. Any fan of Hemingway can tell you that. McCarthy himself is proof:

He squatted and watched it. He could smell the smoke.

He wet his finger and held it to the wind.

McCarthy uses plenty of short sentences, as this excerpt from The Road illustrates. He's even into sentence fragments and uses them to great effect. His range proves my point: only someone who can see ideas in their most pared-down form can begin stringing them together in ways that make an outrageously long sentence work.

If you never plan to write a short sentence in your life—even if your hero is Jonathan Coe, whose 13,995-word novel The Rotters' Club is all one sentence—you should master the short sentence. Doing so will give you better mastery of your long ones and will help you discover ever-better ways of arranging words in order to create meaning and beauty.