English Grammar Drills - Mark Lester 2009

Single-complement verbs

10 Simple Verb Complements

Part 2 Verb Phrases

Both action verbs and linking verbs can take a single complement. We will address the two types of verbs separately.

Action verbs

The complement of a transitive action verb is called an object or direct object. The word object normally implies direct object. (There is also an indirect object, which we will encounter in the next chapter.) An action verb followed by a single object is by far the most common of all types of complements. All objects are either noun phrases or pronouns. (Compound nouns and pronouns are counted as single complements.) Here are some examples, first with noun phrases, and then with pronouns. Verbs are in italics and objects are in bold.

Noun phrase objects

John saw Mary.

Theo washed his new car.

Lois cashed her check.

The bright lights frightened the birds

We met Susan and her friends.

Pronoun objects

I watched them.

Ralph cut himself.

Someone called you.

The children saw us.

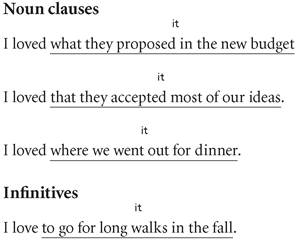

The noun phrase can be any structure that can be replaced by a third-person pronoun: noun clauses, infinitives, or gerunds. Here are some examples:

The nice thing about using a third-person pronoun to identify objects is that you don’t even need to know the technical name for a complex object structure. All you need to know is that it can be replaced by a third-person pronoun.

Exercise 10.2

Underline the objects that follow the italicized transitive verbs. Confirm your answer by showing that a third-person pronoun can substitute for the object.

![]()

1. They heard what you said.

2. The lawyers confirmed that we needed to consult a patent attorney.

3. They emphasized always being on time to meetings.

4. I anticipated having to get a taxi to get to work on time.

5. We finally chose to look for a new apartment closer to our jobs.

6. The contract specified that all the work had to be finished by June 30.

7. We resumed what we had been doing before we had to stop.

8. The audience appreciated how well they had performed.

9. We looked into taking a vacation in Mexico this summer.

10. You need to be more careful in the future.

11. The witness swore that the defendant had not been at the scene.

12. I couldn’t resist making fun of such a ridiculous idea.

13. Nobody could understand his excited shouting.

14. Finally we recovered what we had initially invested in the company.

15. Please forgive what I said earlier.

Separable and inseparable phrasal (two-word) verbs. Phrasal (two-word) verbs are an idiomatic combination of verbs and prepositions or adverbs whose meanings are often wildly unpredictable. Phrasal verbs also pose a major problem for nonnative speakers because they have some very unusual grammatical characteristics. In this section we will only examine what are called separable and inseparable phrasal verbs.

A separable phrasal verb is a compound verb consisting of a verb stem and an adverb. (The terminology for phrasal verbs is unsettled. Many books use the term particle rather than adverb or preposition. The differences in terminology are not very important since there is no real difference in the description of how phrasal verbs work.) Here are three examples that all involve the verb call:

The CEO called off the meetings. (call off = cancel or postpone)

The CEO called up the chairman. (call up = telephone)

The CEO called back the reporter. (call back = return someone’s telephone call)

What is so unusual about the grammar of separable phrasal verbs is that the adverb part of the verb compound can be moved to a position following the direct object, breaking the verb compound apart:

The CEO called off the meetings. → The CEO called the meeting off.

The CEO called up the chair. → The CEO called the chair up.

The CEO called back the reporter. → The CEO called the reporter back.

Note that the adverb part of the compound is moved to a position immediately after the direct object, but before any other adverbs:

The CEO called off the meetings yesterday → The CEO called the meetings off yesterday.

Sometimes learners make the assumption that the adverb moves to the end of the sentence. This is not correct:

The CEO called off the meetings yesterday → X The CEO called the meetings yesterday off.

Even more remarkable, if the direct object is a pronoun, then moving the adverb is obligatory. The sentence is ungrammatical if the adverb does not move.

X The CEO called off them → The CEO called them off.

X The CEO called up him/her → The CEO called him/her up.

X The CEO called back him/her → The CEO called him/her back..

Exercise 10.3

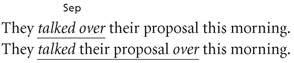

Underline the object noun phrase that follows the italicized separable phrasal verb in each sentence and write the appropriate object pronoun substitute above it. Then rewrite the sentence to replace the object noun phrase with the pronoun. Remember to move the adverb portion of the verb compound to a position immediately after the object pronoun.

1. I dropped off my parents at the station.

2. Jordan wrote down the message on a slip of paper.

3. He looked over the report carefully.

4. The waiter brought in the next course promptly.

5. Susan read back the memo to me.

6. I looked up the answer on Google.

7. George thought through all the complexities very carefully.

8. We talked over all the major points before the meeting.

9. Finally, I got back my stolen bicycle from the police station.

10. She poured out her troubles to her closest friend.

11. We picked up the kids’ toys quickly.

12. Albert turned down the company’s generous offer regretfully.

13. I put together all the loose ends in a neat package.

14. Our company is taking over their company in a friendly merger.

15. The lawyer summed up his case simply and forcefully.

We now turn to the second set of transitive phrasal verbs, inseparable phrasal verbs. These are verb compounds consisting of a verb stem plus a preposition. (The second element in the compound is called a preposition because, unlike the adverbs in separable compounds, prepositions cannot move.) Here are some examples of inseparable phrasal verbs:

She knows about the meeting.

I bumped into an old friend today.

John talked to Mary.

The second element in the phrasal verb cannot move, even if we replace the object with a pronoun:

She knows about the meeting

She knows about it. → X She knows it about.

I bumped into an old friend today.

I bumped into him/her today. → X I bumped him/her into today.

John talked to Mary.

John talked to her. → X John talked her to.

The obvious problem for English learners is how to tell which phrasal verbs are separable and which are inseparable. There actually is a way to predict (to a degree at least) which compounds are separable and which are inseparable, but it isn’t simple. It turns out that the lists of adverbs and prepositions used in separable and inseparable verb compounds are nearly mutually exclusive. That is, if you know what you are looking for, you can make a good guess based on the second element in the compound whether the compound is separable or inseparable. Here is a list of the most common adverbs and prepositions used in phrasal verbs:

Separable adverbs Inseparable prepositions

apart about

away after

back against

down at

in by

off for

on from

out into

over of

through on

up through

to

with

What is remarkable about the list is that there are only two words, on and through, that appear on both lists. With the exception of these two words, you can predict with a fair degree of accuracy whether a phrasal verb is separable or inseparable by looking at the second element in the compound. It is probably worth your time to memorize the list of separable adverbs. (You do not need to memorize both lists. The list of separable adverbs is longer, and separable adverbs are much less common than inseparable prepositions.) Sometimes this rule of thumb (“rule of thumb” is an English idiom meaning an imperfect, but nevertheless helpful guide) will be wrong, but it will be right far more often than guessing will be.

Exercise 10.4

Label the italicized phrasal verbs as Sep (for separable) or Insep (for inseparable). If the verb is separable, confirm your answer by moving the adverb to a position immediately after the object.

1. Please look after my plants.

2. James always played down the size of the problem.

3. He consulted with everybody involved in the project.

4. They split up the original team.

5. He hinted at the possibility of a new job.

6. They guarded against getting over confident.

7. I pointed out all the problems.

8. A policeman pulled over the red convertible.

9. I stand by my original statement.

10. The terrorists blew up a gasoline truck.

11. She learns from her mistakes.

12. He was trying to paper over his involvement.

13. Let’s talk about our problems.

14. We need to pare down our expenses.

15. They prayed for a swift recovery.

16. We set up the display tables quickly.

17. He hardly blinked at his outrageous offer.

18. We turned in our badges at the desk.

19. Did you hear about the new office?

20. I kept playing over the entire conversation.

Linking verbs

In linking verbs, the subject is not an actor performing any action, and the complement is not the recipient of any action. Rather, the complement is used to describe some attribute or characteristic of the subject. The verb is called a linking verb because it links the complement back to the subject.

Linking verbs can take three different types of complements: (1) noun phrases (including pronouns), (2) predicate adjectives, and (3) adverbs of place and time.

If the complement of the linking verb (Link) is a noun phrase, it is called a predicate nominative (Pred Nom) rather than an object. Here is an example:

![]()

Note that the subject Thomas and the predicate nominative a football player are one and the same person:

Thomas = a football player.

This identity of subject and predicate nominative is the key to recognizing a linking verb when the complement is a noun phrase. Here are some more examples:

Sally became a professional tennis player.

Sally = a professional tennis player.

Cinderella’s coach turned into a pumpkin.

Cinderella’s coach = a pumpkin

I felt like a complete idiot.

I = complete idiot.

In an action verb sentence, of course, the subject and the object do not refer to the same person or thing. For example:

Sally met a professional tennis player.

Sally ≠ a professional tennis player

Cinderella's coach impressed her sisters.

Cinderella’s coach ≠ her sisters.

I talked to a complete idiot.

I ≠a complete idiot.

Exercise 10.5

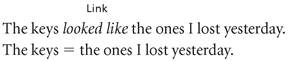

Label the italicized verbs as Act for action verb or Link for linking verbs. Confirm your answer by using equal (=) and unequal signs (≠) to indicate whether the subject and the complement refer to each other.

1. The keys unlock the storage cabinet.

2. The plan seemed a good idea at the time.

3. The board approved the plan.

4. Richard became a highly successful salesman.

5. Her new car is a Ford.

6. Unfortunately, his new mansion looks like a cheap motel.

7. Louise greatly resembles her sister Thelma.

8. Louise called up her sister Thelma.

9. The new nominee really seems like a good choice for the job.

10. The housing market has turned into a complete disaster.

11. My first choice would be an apartment near where I work.

12. Albuquerque resembles a typical city in the 1960s.

13. The actor seemed a man in his midfifties.

14. My brother ended up a lawyer in a big law firm.

15. What you can see is all that we have left.

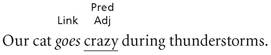

The second complement type that linking verbs can take is a predicate adjective. Here are some examples with the linking verb in italics and the predicate adjective in bold.

Senator Blather’s speech was pretty dull.

The soup is cold.

John got very angry.

The weather turned dark and stormy.

Terry’s chili is too spicy for me.

Stay warm!

Let’s get ready.

Exercise 10.6

Label the italicized verbs as Act for action verb or Link for linking verbs. Underline the complements of the linking verbs and label them Pred Adj (for predicate adjective) or Pred Nom (for predicate nominative) as appropriate.

1. On hearing the bad news, Agnes turned deathly pale.

2. The note sounded flat to me.

3. George seemed terribly upset about something.

4. The situation could easily turn ugly.

5. You look ready to go.

6. Everyone noticed his strange behavior at the party last night.

7. After his long illness, Jason looked like a ghost of his former self.

8. Over the years they have grown closer to each other.

9. The day was getting terribly warm.

10. Please remain calm.

11. The wine has gone bad.

12. I felt much better after seeing the doctor.

13. They looked ready to go.

14. Our simple plan has turned into a huge project.

15. All the indicators appeared positive.

Many hundreds of true adjectives are derived from the present participle form of verbs. For example, here is the true adjective amusing used both as a noun modifier and as a predicate adjective:

Noun modifier: He told an amusing story.

Predicate adjective: His story was amusing.

It is sometimes very difficult to tell predicate adjectives apart from the same word used as part of the progressive tense. Here is an example:

Predicate adjective: The story was amusing.

Progressive verb: His story was amusing the guests.

As you can see, amusing is a predicate adjective in the first example, but a main verb in the progressive form in the second example. In both cases, amusing follows the verb be. The two sentences look alike, but are actually built in different ways:

Fortunately, there are several reliable tests to help us decide when a present participle word form is being used as predicate adjective following a linking verb and when it is being used as a main verb in a progressive verb construction.

If the present participle is being used as a predicate adjective, it can almost always be modified by the word very. For example:

His story was very amusing.

When we try to use very with a present participle used as a main verb, the result will always be ungrammatical:

X His story was very amusing the guests.

If the present participle is being used as the main verb in a progressive construction, we can usually paraphrase the sentence by changing the progressive construction to a simple present tense or past tense, for example:

His story was amusing the guests. → His story amused the guests.

When we try to turn a predicate adjective into a main verb, the result will always produce an ungrammatical sentence. For example:

His story was amusing. → X His story amused. (who?)

Amused is a transitive verb that must have an object.

Here is another pair of examples:

(1) The report was discouraging.

(2) The report was discouraging everyone.

In (1), we can tell that discouraging is a predicate adjective because we can modify it with very:

The report was very discouraging.

When we try the very test with (2), the result is ungrammatical:

X The report was very discouraging everyone.

In (2), we can tell that discouraging is part of a progressive verb construction because we can paraphrase the verb construction with a past tense:

The report was discouraging everyone. → The report discouraged everyone.

Exercise 10.7

Apply the very and paraphrase tests to each sentence in the following pairs of sentences.

The repeated failures were upsetting.

The repeated failures were upsetting everyone.

Very test: The repeated failures were very upsetting.

Paraphrase: X The repeated failures upset. (who?)

Very test: X The repeated failures were very upsetting everyone.

Paraphrase: The repeated failures upset everyone.

1. The movie was frightening.

The movie was frightening the children.

Very test: ...

Paraphrase: ...

Very test: ...

Paraphrase: ...

2. My boss is demanding.

My boss is demanding an answer.

Very test: ...

Paraphrase: ...

Very test: ...

Paraphrase: ...

3. His suggestions were surprising.

His suggestions were surprising everyone.

Very test: ...

Paraphrase: ...

Very test: ...

Paraphrase: ...

4. The mistakes were alarming.

The mistakes were alarming everyone.

Very test: ...

Paraphrase: ...

Very test: ...

Paraphrase: ...

5. The company is accepting.

The company is accepting applications.

Very test: ...

Paraphrase: ...

Very test: ...

Paraphrase: ...

The third type of complement that linking verbs can take is an adverb of place or time. Here are some examples of both kinds of adverbs:

Adverb of place complement

The picnic is at the beach.

Our apartment was on 53rd Street.

We were there.

Adverb of time complement

The meeting is at ten.

The game is Saturday afternoon.

That was then; this is now.

One of the differences between adverbs of place and time as complements of linking verbs and ordinary optional adverbs is that we can never delete complements. Complements, by definition, are grammatical structures required by a verb to make a complete sentence. If we delete adverbs that are complements, the resulting sentence will be an ungrammatical fragment. Optional adverb modifiers, on the other hand, can always be deleted without affecting the grammaticality of the sentence. Compare the result when we delete the adverbs from the following sentences:

Complement: The meeting is on the third floor.

Optional adverb modifier: I attended the meeting on the third floor.

When we try to delete the adverbs from the two different sentences, the deletion of the complement results in an ungrammatical sentence, while the deletion of the optional adverb from the action verb sentence has no effect on the grammaticality of the sentence:

![]()