Painless Reading Comprehension - Darolyn “Lyn” Jones Ed.D. 2016

Preparing for what’s next

Different types of reading

Think about a video game. When you play a video game, you have to work your way through each set of obstacles to get to the next level. To be successful at the game, you must know what to expect at each level of the game. Once you have played a few times, for example, you know the one-eyed monster with the green horn and hairy arms will come out in the middle of level two and attempt to destroy you or that the hungry ogre will try to eat you at level four. And, you usually share this information with your friends. Several years ago, a group of my students would converge in my classroom every day prior to our sixth period meeting time and share tips and tricks with each other on how to play a popular video game.

Think of a textbook as a video game. Once you have seen what happens, you are ready for it the next time. You can continue to build civilizations. You can zap out the monster who tries to destroy your hard work. More importantly, though, you can navigate the textbook and find the treasure, which is being a successful reader and learning the information you need.

Now that you have a sense for how the whole textbook is outlined, let’s look at specifics. Even though each chapter may be on a different topic, each chapter will be organized the same.

Channeling through the chapter

Choose any chapter in a textbook and channel, travel, or move through it finding the following information so you can see how the chapters are set up.

Goals and Objectives. Are there any goals or objectives listed at the beginning of the chapter? They will probably be listed as statements of fact. If so, list them.

Special Markings. Skim the chapter. Do you see any subheadings in boldface or italics? If so, list them. These subheadings are smaller ideas that are part of the larger ideas. Also, jot down what you know about the topics listed in boldface or italics.

Graphics or Sidebars. Are there any sidebars (boxes with words in them off to the side) or graphics like pictures, charts, or maps in the chapter? Choose one and tell what it says or what it is trying to show.

Exercises. Are there exercises either at the end of each section or at the end of the chapter? Look at the first exercise and at the last exercise. What are they asking you or telling you to do?

Summary. Is there a summary at the end of the chapter or a conclusion? How is it marked? Does it say “conclusion” or “reflection” or something else? Is it in boldface or italics?

Let’s Practice!

Find the five items we just discussed for Chapter Five, “Keeping What You Read in Your Head,” of this textbook, Painless Reading Comprehension.

Goals and Objectives. The introduction to the chapter explains the problem with keeping what you read in your head, and then the two key methods are listed as:

✵ Go back and skim for the information you need OR

✵ Go back, reread, and take notes.

This lets you know that the entire chapter is centered around those two key ideas. And, if you examined all the chapters, you would see that I offer anywhere from two to five key ideas in each chapter that are to be covered.

Special Markings. The subheadings appear on a separate line by themselves, above the text they are discussing. They are: What Do I Do When I Am Finished Reading?, Skimming for Information, Rereading Part of the Text, and Raising Questions Aids Your Reading. Titles of the reading selections are set apart from the explanatory text and include English Selection: “A School Ghost Story” by M. R. James; English Selection: “I heard a Fly buzz” by Emily Dickinson, and English Selection: “To J.W.” by Nora Pembroke. Again, this is true for every chapter. Subheadings and reading selections are set off from the rest of the book with special type.

Graphics or Sidebars. Images are scattered throughout the chapter. I only use artist images in this textbook. The illustrations are usually humorous but are also a visual reminder of the topics. For example, whenever you see an image of a string tied to a finger, be sure to read the passage. It’s an important reminder. Some, however, are serious and go along with the reading selections.

Exercises. The exercises are located throughout the chapter under the heading “Let’s Practice.” The first exercise asks the reader to skim the story on Agnes Vogel. The first question asks: “Where is Agnes Vogel from? What was her life like prior to the war?” The last question asks: “What does Vogel mean when she says the Nazis were ’liquidating the Ghetto’?” In every chapter, each time I tell you about a new way to read, I ask you to practice it as well. I also offer you student models so that you can see firsthand how to do it.

Summary. There is no marked summary or conclusion, just final thoughts in a paragraph at the end of the chapter where I ask you to think about what you have learned in a section called “Reflect on what you have learned.” By asking you to reflect, I am asking you to write your own summary. There is also a Brain Ticklers section, which quizzes you over key points in the reading.

Let’s Practice!

Select any of your current textbooks. Once again, you might choose the textbook for a class in which you are struggling. Channel through the chapter looking for the five items we just discussed.

Knowing how the textbook is set up will save you time and make you a better reader. Each time you go to read your textbook chapter or use the reference sections for an assignment, you won’t have to dig through it trying to find the information. You will know what to expect so that you can just concentrate on the idea the words are trying to convey.

Breaking the cryptic code of textbooks

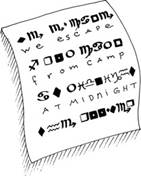

You and your friends have something in common with textbooks. You both have your own set of special words or phrases. Reading a textbook can be like reading an encyclopedia. There is no “Once upon a time . . . .” There aren’t usually vivid scene details that help you visualize. Images won’t easily pop into your head as they do when you read fiction. You must work harder to create images when you are reading a textbook.

As you have already discovered, a textbook contains thousands of facts, examples, and questions that are broken up into chapters, whereupon those chapters are broken up into sections, and consequently those sections are broken up into words.

How do you take in all of those words and make sense of them? No one would expect you to speak fluent French unless you were French or had been taught how to speak fluent French. The same logic can be applied to textbooks. You need to be taught how to read a textbook. You don’t have to learn to speak it or write it, but you do have to learn to read it in order to be a successful reader and learner.

We have seen that the author or editor has already grouped and organized the information in a textbook in a meaningful way. For example, a book on the Civil War is going to be broken down into sections such as causes, battles, and consequences. But, it is still your responsibility to read the information, find the main ideas, and think about what they mean.

To actively read a textbook, you must be alert and awake! No napping or drooling allowed. Think about running a mile. It takes a great deal of effort and stamina. That’s how it is when you read a textbook. It’s not a short run, and it will take some energy and enduance on your part. But, when it’s over, you will feel better because you met a goal and because your body received a workout. The good thing about reading a textbook, though, is you won’t have to take a shower and your hair won’t be messed up for the rest of the day.

Textbook reading strategies

Stick by the following rules when reading a textbook.

1. If there is a section or chapter summary at the end, read that first! It will tell you the key points to find when you read.

2. Read the information. Don’t skim the first time. You don’t have to understand every single word, but you do need to read the text in its entirety.

3. While you are reading, pay attention to the vocabulary or the words used in the text. Remember Chapter Four? Use the flag words—such as so that, as a result of, for example, just as, above all, and remember that—to help you to see how words are put together to create meaning. Also, use the context around a word to figure out a word’s meaning. And if there is a glossary, use that too!

4. Textbooks start out with basic information and then move into more complex and detailed information. After you have read a few paragraphs, stop and think about what you have read. If you don’t understand, then go back and reread. Don’t go forward; if you aren’t getting the more basic information, you won’t understand the complex.

5. When you find a main idea or make a connection, jot it down on sticky notes or in your notebook. Remember that taking notes while you read keeps you from napping or drooling.

6. If you see a chart, graph, or picture, stop and “read” it too. Look at it and think about how it fits with the words.

7. There will probably be a summary at the end of the chapter, but not at the end of each section. So, write your own summary for each section. This will help keep your reading and thinking in check.

8. Stop and talk. With a study buddy or friend, stop at the end of each section and talk about what you read. You can use the sticky note prompts to keep your conversation going.