Painless Reading Comprehension - Darolyn “Lyn” Jones Ed.D. 2021

The 3 Ds: Determine, decide, and deduce

Reading strategies

Chapter Two talked about thinking about what you are going to read before you start reading it, about the three Ds: determine, decide, and deduce!

1. Determine your purpose. Why are you reading this? Answering with The teacher told me to doesn’t state your purpose. Try again. Do you have to memorize the information for a test? Do you have to summarize what you read? Do you have to write a report, explaining the events and motivations? Do you have to make an online poster, using Glogster, representing symbols about the topic? Do you have to act out a scene? The possibilities are endless. If you aren’t sure, then reread the assignment sheet or ask your teacher to clarify. To be successful on the assignment, you need to understand why you are reading it.

2. Decide what kind of material you are reading. Is it informational—just facts and dates? Is it fiction—a story? Is it a word problem you will have to solve? Is it a process—like how a piece of wood becomes a fossil? Just as you speak in different languages in different situations, you read differently depending on what you are reading.

3. Deduce how much time you will need to do the reading. Deduce or make an educated guess as to how long you will need to do the reading, and then add some extra time to that. It may take you longer to read information than to read a fictionalized story or vice versa. Have you ever tried to read a fifteen-page chapter in study hall thirty minutes before it is due? You probably weren’t successful. Give yourself plenty of time. Some people need longer than others, and that’s okay. There is no award given for speed-reading. People who say they can read really fast may be able to, but they may just be decoding and not reading. You know the difference, so don’t feel pressured to read faster. The reward is that you understand what you have read. Only you know how long it takes you. So, you need to set aside that amount of time and some extra time in case you run into problems. As you read more and practice the techniques in this book, you will discover that you will be able to read faster. But remember, reading is a process. You have to start at the beginning first.

Let’s practice!

For each of the practice reading selections in this chapter, I will present you with an assignment so that you will know your purpose for reading. And, for each reading selection, you will have two to three graphic organizers with which to practice each of the reading steps: before, during, and after.

YOUR ASSIGNMENT:

Read the following excerpt of a speech delivered by Frederick Douglass in 1852, and explain in a paragraph why Douglass believes that the Fourth of July is not a holiday for a black man to celebrate.

Before reading: Two-Sided Notes

Remember that you can organize Two-Sided Notes in a variety of ways. Here I am asking you, before you read the essay on Frederick Douglass, to write down what you know about Frederick Douglass and what you think about what you know. For example, on the left-hand side, I might write down, “Frederick Douglass lived during slavery times.” And on the right, I might write down, “I think he became free.”

Social Studies Selection: “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” a speech delivered by Frederick Douglas on July 5, 1852

Introduction

The papers and placards say, that I am to deliver a 4th of July oration. It is the birthday of your National Independence, and of your political freedom. Fellow Citizens, I am not wanting in respect for the fathers of this republic. They were peace men; but they preferred revolution to peaceful submission to bondage. With them, nothing was settled that was not right. With them, justice, liberty and humanity were final; not slavery and oppression. You may well cherish the memory of such men.

Friends and citizens, I need not enter further into the causes which led to this anniversary. Many of you understand them better than I do. You could instruct me in regard to them. My business, if I have any here today, is with the present. We have to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and to the future. Fellow citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here today? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence?

The Fourth of July Is Yours, Not Mine

I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me.

This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, is inhuman mockery. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak today? Above your national, tumultuous joy, I hear the mournful wail of millions whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday, are, today, rendered more intolerable by the jubilee shouts that reach them. My subject, then fellow-citizens, is AMERICAN SLAVERY.

What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?

A day that reveals the injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. But I fancy I hear some one of my audience say, it is just in this circumstance that you and your brother abolitionists fail to make a favorable impression on the public mind. Would you argue more, and denounce less, would you persuade more, and rebuke less, your cause would be much more likely to succeed. But, I submit, where all is plain there is nothing to be argued. What point in the anti-slavery creed would you have me argue? Must I argue that a system thus marked with blood, and stained with pollution, is wrong? No! I will not. I have better employments for my time and strength.

At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. Oh! Had I the ability, and could I reach the nation’s ear, I would, today, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

Conclusion

What, to the American slave, is your Fourth of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.

To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass-fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.

During reading: Vocabulary staircase

Create a vocabulary staircase for each of the following three words used in the reading selection on Frederick Douglass: reproach, rebuke, and denunciation.

✵ Remember that at the first step, you look the word up in the dictionary and write down the first or second definition.

✵ At the second step, you decide if the definition has a positive connotation, a neutral connotation, or a negative connotation. Recall the discussion of all the different connotations associated with the word heart? The word heart has a positive connotation because, as noted earlier, you think of it as one of the most important organs in your body, relate it to having great spirit, or associate it with love. Connotation is the definition and meaning you associate with the word. Remember to assign a smiley face to a word that has a positive connotation, a straight face to a word that has a neutral connotation, and a frown to a word that has a negative connotation.

✵ At the third step, you provide a synonym for the word. A synonym is a word that has the same meaning or nearly the same meaning as the word you are defining. For example, a synonym for confidant, who is someone you can tell your secrets to, is friend.

✵ At the fourth step, you offer an antonym for the word. An antonym is a word that has the opposite meaning of the word you are defining. For example, an antonym for the word confidant would be enemy.

✵ At the fifth step, you use the word in a sentence.

✵ The final step, the last step before the top of the staircase, is a fun step. Draw a picture of the word!

After reading: SAM the Summarizer

Using the assignment as a guide, reread the speech given by Frederick Douglass and explain in a paragraph why Douglass believes that the Fourth of July is not a holiday for a black man to celebrate. Complete the SAM the Summarizer reading organizer by finding important words, phrases, or whole sentences that discuss the role of Frederick Douglass and why he doesn’t think the black man should celebrate the Fourth of July.

1. Prepare to summarize. Write down your purpose for reading—in other words, your assignment. What are you reading for? What facts, people, events, dates, and so on are you looking for? List the keywords from the assignment.

2. Analyze and decide what is important. There are eight paragraphs. Put two paragraphs together and come up with important words, explanations, or opinions of the author that help to answer your assignment question.

3. Map it out! Using the author’s words, explanations, and opinions and your own words, summarize the answer to the assignment.

Before reading: KWHL Chart

A KWHL Chart asks you what you know about a topic, what you want to know, how you will find out, and what you have learned. KWHL Charts are an effective way to think about what you know and then, as you read, jot down questions you might have about the reading. Finally, it allows you to summarize what you have learned after reading. Before you read the following lecture on commas, write down or type what you know about commas. Write down anything you can think of. Try to write down at least three ideas or more, if you can. You might, for example, write, “A comma is used to show a pause.”

Before you start reading, write down or type what you want to know about commas. Now, please don’t say you want to know nothing! Of course, you want to know something. Grammar and mechanics are confusing, and unless you are a trained copy editor, you probably have some problems remembering when you should use commas. Again, try to get down at least three questions. You can even think in terms of the rules. For example, I might ask, “Why do some people put a comma before the word and in a list and other people don’t? What is the actual rule?” If you are still having problems coming up with what you want to know, then look at some writing. Look at this page or any other page with writing and notice how the commas are used. If you don’t know why a comma is used, then write down the sentence and ask why that comma is used! After you have written down three questions, start reading. As you are reading and you come up with other questions, jot those down in the W column. And say how you will find out the answers to your questions. Will you read and find information that specifically answers your question about why and when you put a comma before the word and?

Finally, when you are finished reading, write down what you have learned. Again, don’t write down rules you already knew how to use. Record the new rules or tricks you learned from the reading. Or, explain how, before you started reading, you were confused about a certain rule or use but now, after reading Rowe’s piece on commas, you understand.

YOUR ASSIGNMENT:

Before, during, and after reading this next piece, “Commas” by Kim Rowe, you will practice working with the KWHL Chart.

|

K |

What do I know about commas? |

|

W |

What do I want to know or should I know about commas? |

|

H |

How will I find out about commas? |

|

L |

What have I learned about commas? |

English Selection: “Commas”

by Kim Rowe

Commas Are Hard!

Commas are probably one of the most difficult types of punctuation to learn. Once it clicks, you will understand the use of commas the rest of your life. However, getting to the “understanding point” can be a long journey!

Many adults misuse commas. In fact, just the other day I received an email from a friend that had several comma errors in it. Luckily, this email was only sent to me as a friendly note and not to a boss or an important business client who would expect a more professional, error-free email. More than likely, my friend was writing quickly, and she was not cautious about her grammar. Yet, her errors would have been a big deal if her email was sent to a potential employer; she probably would not receive the job. This is why understanding how to correctly use commas is so important.

Why Use Commas?

Some of my students think that I am crazy when it comes to teaching them about commas. Some of them even call me the “Comma Queen,” at least to my face! Maybe it is because I try to drill correct examples into their brains so using commas properly becomes second nature to them. I would like my students to understand how to use commas in a split second—kind of like how quickly Scooby Doo eats a Scooby snack.

One important item to remember is that the sole purpose of using commas is to make sentences easier to understand. A comma tells the reader that he/she should pause when reading, or a comma shows that items should be separated to make the understanding clear.

Let’s look at the following example sentence to start:

Example: Mary Ann and Sue went to the store and bought chocolate ice cream vanilla fudge cracker jacks and bread.

Yikes! When reading this sentence without commas, I do not know if two or three people went to the store. Is it Mary Ann or Mary as well as Ann? I also do not know if they bought chocolate and ice cream or if they bought chocolate ice cream. Did they buy vanilla and fudge or vanilla fudge? The simple use of a few commas would clear up this sentence’s meaning.

Example: Mary, Ann, and Sue went to the store and bought chocolate ice cream, vanilla fudge, cracker jacks, and bread.

As mentioned earlier, learning comma usage can be tricky. I try to make learning about commas easy for students. First, I start by helping students realize that practically everyone has misused a comma here and there. Secondly, I try to emphasize that students need to learn the common comma mistakes and learn to not make them.

Another important item is that students should put comma rules immediately into practice. Personally, I think it is pointless for students to memorize the comma rules and be able to recite them word for word. What good is it to know that a comma should be used after two or more introductory prepositional phrases if someone does not even know how to pick out a preposition? It is much more beneficial for students to see an example of how to use the rule in writing. Take, for instance, the following comma rule:

Comma Rule: Use a comma after two or more introductory prepositional phrases.

Sentence Example: For many years Jamal has been going to King’s Island with his family.

In this first example sentence there is only one prepositional phrase. According to the rule, no comma is needed. Let’s look at a second example where a comma is needed according to the comma rule above.

Sentence Example: After three hours of shopping, Ashya was ready to go home.

In this sentence we see that there are two prepositional phrases (“after three hours” and “of shopping”). This is where a comma is needed.

Common Mistakes

As mentioned earlier, one of the items I emphasize is to learn about the common mistakes people make with commas. Students who know these common errors, and keep them out of their writing, will really improve their writing quality and make fewer errors. Some common mistakes that people make are placing a comma in a sentence when they think there is a pause, not placing a comma in a comma series, and placing a comma incorrectly when connecting two main clauses. To help you learn more about these common errors, take a look at the following three examples:

Common Error: Placing a comma in a sentence when you think there is a pause.

Rule: There is no rule requiring a comma for a pause in a sentence. Let’s look at an example:

Sentence Example Error # 1: Jim needs a break, from mowing the lawn.

Sentence Example Correction: Jim needs a break from mowing the lawn.

Common Error: Not placing a comma in a comma series.

Rule: Use commas when a comma series occurs. Let’s look at an example:

Sentence Example Error # 2: Jiale plays basketball, football and soccer.

Sentence Example Correction: Jiale plays basketball, football, and soccer.

Common Error: Placing a comma incorrectly when connecting two main clauses.

Rule: Use a comma to connect two main clauses. Let’s look at an example:

Sentence Example Error # 3: This summer Kayla is going to Alabama and she is going to visit with her grandmother and aunties.

Sentence Example Correction: This summer Kayla is going to Alabama, and she is going to visit with her grandmother and aunties.

Comma Tips

Try to think of each comma rule separately. Look at a sentence and try to figure out what rule should be applied. For example, if you do not see introductory prepositional phrases, then you can rule out the two prepositional phrase rule. Basically, fit a rule to a sentence. If students think of commas with an open mind and have confidence, then they can truly understand comma usage. The next time you study commas in English class, relax and remember to break down the rules.

The next reading selection is a scene from the play Mama’s Boys, Care Bears, and Fat Girls by New York playwright Tyler Dwiggins. This is one of my favorite scenes because it illustrates two young adults sharing their true attitudes about love and life. The selection after that is a blog titled “Building a Rainbow” by young adult author Barbara Shoup.

Before reading: Word Write

Before you read the scene from Mama’s Boys, Care Bears, and Fat Girls, I want you to do some writing. I want you to think about the words you will run into when you read and what they might mean.

With a Word Write, you choose ten to fifteen words that are from the first section or if the section is short, such as this one, from the entire piece. Choose an equal number of words you do know and words you don’t know. Choose nouns like names and places and verbs that show action. Write the words down as they appear in the reading. Write a paragraph using any form of the selected words and in any order you want. Of course, you can use other words. You would have to do so in order to write a whole paragraph! Just make sure you use all the words selected. And don’t worry if you use the words incorrectly.

Here is how a Word Write helps you to read. You see the words standing alone, and then you give them meaning by writing them down in sentences. Then, after you start reading the story, play, or piece of nonfiction, you will see the words again. It is in that second seeing that you will compare how you used the words to how the author used them. This will help you to pay closer attention to your reading and keep you alert during reading!

For this exercise, you will be given ten words from the play to use. Again, write your own paragraph using all the words before reading any of the play. Have fun with it! The purpose of a Word Write is to get your brain thinking about the important words used in the reading selection. If you don’t know what a word means, guess! Create your own meaning for it.

Word Write words for Mama’s Boys, Care Bears, and Fat Girls

platonic

struts

flamboyance

grungy

illusion

adoring

shuffle

unconditional

breed

cynical

YOUR ASSIGNMENT:

Compare and contrast the characters Nate and Roxie in the play Mama’s Boys, Care Bears, and Fat Girls. Compare and contrast the girl in prison to the author, Barbara Shoup, who is talking with the girl. How are they alike and how are they different?

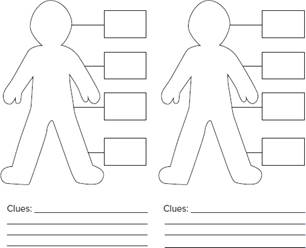

During reading: Caricature of a Character

One reason why the play or the blog you are about to read might be difficult is that there are different characters or people being introduced at various points. Your assignment for both reading selections is to compare and contrast. The play has two fictional characters and the blog has two real people. Both of these reading selections are contemporary, and you should be able to relate to their teen discussions about love and happiness.

While you are reading the play, keep track of the two main fictional characters, Roxie and Nate, and of the two real people, the girl in prison and the author, Barbara. As you hear from each of them and about each of them, write down a description of each character or person. When you describe each one, you need to describe any physical characteristics as well as any mental features, meaning what the character or person is thinking or feeling. Because you may not get all the details you need, you may have to infer meaning or make an educated guess based on the clues the author presents. For example, in the popular Harry Potter series, you know that Ron has red hair, is short, isn’t the best student, and is jealous of Harry. The author always talks about how short Ron is compared to his twin brothers, discusses Ron’s red-haired family, shares Ron’s feelings of never getting any attention compared to Harry, and reveals how Ron is always asking Hermione for homework help.

If you use your own words to describe the characters or the people in what you are reading, they should begin to make sense to you. You will better understand their motivations and actions or why they say and do what they say and do. After you are finished reading, reread your descriptions and explain how you know what you wrote down. Skim back through the reading and find proof if necessary. Write down words or passages from the story that back up what you think. Use the characters’ words to back up your words! If you need to add more to your descriptions list, do so after you are finished. The Caricature of a Character is a fun and effective tool to use when you must read a story where there are many characters or people and/or when you have an assignment where you need to analyze and write about characters.

To use this reading organizer, reproduce the following figures that look like gingerbread men. You can even draw them any way you want. They can even be stick figures. If you are computer savvy, you can even create an avatar! As you encounter a new character or person in the scene, story, blog, or whatever you are reading, write down the character or person’s name above the figure. Then, draw the character’s physical features that you see through the author’s words. Inside of each of the character’s heads, describe the character’s personality. Inside the boxes, describe the actions the character’s body does. Below each figure write down what clues you have that support your descriptions. Find words, phrases, or sentences in the reading that support your description.

A Scene from Mama’s Boys, Care Bears, and Fat Girls by Tyler Dwiggins

Enter NATE and ROXIE, who are platonic best friends. They walk on stage and sit on a park bench, watching pedestrians stroll past them. NATE is dressed in an unassuming T-shirt and jeans. ROXIE, as usual, struts like Mick Jagger and dresses with the flamboyance of a lost Spice Girl. A pair of grungy boys roll past on skateboards, ogling Roxie. Roxie notices and winks at them with a megawatt smile on her face.

NATE: Ew, Roxie. What are you doing?

ROXIE: I’m giving them the illusion that they have a shot with me. Call it community service.

(An elderly couple shuffles by, holding hands and looking truly in love.)

NATE: Now, see that’s what I want.

ROXIE: You want to have a pair of old people? That can’t be legal, Nate.

NATE: No, I mean . . . I want that completely adoring, unconditional love. The kind of love where you don’t care that your husband wears pants so high that they are probably chafing his nipples or that your wife has an afro that looks like she stole the fattest section of a snowman and plopped it on her head.

ROXIE: Yummy?

NATE: No, Rox, seriously. Look at them. Look at the way they shuffle along, holding hands, like they’ve got all the time in the world. You can tell that they’ve always loved each other, and they always will. Just that feeling like you can totally be yourself without having to change or keep secrets from one another, you know? Like where you just know they’ll never leave.

ROXIE: Oh, Nate . . . Don’t you know? Worrying that you’ll lose somebody and trying to keep them around is half the fun. The joy is all in chasing somebody around while trying to look like you’re not the one doing the chasing.

NATE: That’s not love, Roxie. That’s like something on the Discovery Channel.

ROXIE: Oh, love, Nate? Really? (She says the word “love” like it’s something sour that she has to spit out of her mouth.) Give me a break, Nate. “Love” is for mama’s boys, Care Bears, and fat girls to dream of. It’s not actually real, Nate. Love is for people who are too afraid to do what mammals are supposed to do, which is find somebody you like the looks of, breed, and move on. Love is not what I’m after.

NATE: That’s a smidge cynical, yes?

ROXIE: It’s a smidge genius, is what it is.

NATE: But I wuuuv youuu, Roxie. (Nate flings his arms around Roxie and squeezes her into a bear hug. She pretends to be annoyed.)

ROXIE: That is because you are the only good boy left, Nate.

NATE: Not true. But really . . . I do love you, mi amiga. You know that, right?

ROXIE: I know, doll. I know. Now stop hugging me. You’re ruining my image.

“Building a Rainbow” by young adult author Barbara Shoup at barbarashoup.blogspot.com

Introduction

Black, white, Hispanic, the twenty young women assigned to the Writers’ Center of Indiana’s third memoir-writing workshop at a prison for girls file into the visiting room for the first session looking wary. They’re all dressed exactly the same: khaki pants, ugly green V-necked shirts, plastic sandals. Their hair is poorly cut, their complexions pale from being locked up inside. No makeup is allowed. Some have crudely done tattoos; in some cases, their arms are criss-crossed with small white scars, evidence of cutting. Too many look dazed by the too-high dose of whatever drug some medical bureaucrat prescribed to control them.

The volunteers—writers, teachers, college students—call the names of the girls in their group and the girls go sit down, glancing back at the others still in line. There are six marbled composition books on each table, two each: the one with the “Building a Rainbow” image pasted on front for the writing we’ll do in class, the other for the writing they’ll do between sessions, on their own.

Building a Rainbow

“These are for us?” at least one girl at each table asks.

They ask it every year and, every year, are astonished when we say yes.

I talk to them about the rainbow image, a scaled down version of the huge poster that hung in my office years ago, when I began teaching. “I grew up in a poor family,” I tell them. “My dad drank. My mother was sad. I had big dreams, but I thought whether or not they’d come true was all about being lucky or not being lucky.

“I was confused about happiness, too. I thought it was about how nice your house was, how much your parents didn’t have to worry about money, how much stuff you had. I thought it was a state of being. Once happy, you stayed happy, like being in a place.

“But, in fact, you have to make dreams come true,” I say. “Look at the rainbow. It’s under construction, covered with stick people painting, hammering, working cranes to put things in place.

“And, as for happiness, it’s no more than a collection of mostly small moments, strung like beads on a necklace, throughout our lives.

“You can learn how to take the hundreds, maybe thousands of small steps you’ll need to take to make your dreams come true; you can learn to recognize and cherish those small moments when you feel right with the world and to build on them until the weight of happy moments is greater than the ones that hurt you and make you sad.”

They listen.

I Remember a Yellow Ball

They open their “Rainbow” notebooks and, as instructed, write “I remember, I remember,” dredging up all kinds of memories—happy and sad. I ask them to pick one happy memory and do the “I Remember” exercise again, dredging up details about that one thing. Willingly, they bend their heads to the task—all but one.

“I don’t have any happy memories,” she says, scowling.

I go and sit beside her. “None?” I ask.

“None.”

“When you were little?”

She shakes her head.

“Toys?” I ask.

“I had a yellow ball.”

I ask her to tell me about it.

“It was big. My brother busted it when I was twelve, and all the air went out of it.”

But she smiles (for the first time) when she says this. “I loved that ball,” she goes on. “I had it from when I was three and my brother was scared I was going to beat him up when I found out.”

“But you didn’t?”

“Nah,” she says. “It was funny he was so scared, though.”

I ask if she remembers when she got the ball, and she does. Her uncle bought it for her at Walmart. It was at the top of a tall bin full of balls of all colors and sizes. There were yellow balls closer to the bottom, and her mom said she should just get one of those. But she wanted that yellow ball. Her uncle tried to climb the bin, but it was too rickety. So he went to get an employee to help and, when the man got the ball and held it out to her, her uncle told her to say thank you.

“I ran up and hugged his legs,” she says. “I loved my ball so much. It looked like the sun. Yellow is my favorite color, ever since then.”

By now, she’s talking and writing. Smiling, even laughing at what she remembers. Her mom was wearing a blue dress, her uncle an orange shirt that made him look like a huge tangerine.

Near the end of the class, I ask if anyone would like to read what she’s written to the group, and she raises her hand.

So there is one remembered bead for her necklace of happiness: the day she got the yellow ball.

Conclusion

And one, I hope, for the memory of writing about it. There’s a bead for my necklace of happiness, too: watching her face change as writing took her back to that happier time; listening as she read her memory aloud; thinking maybe, maybe it will make a difference.

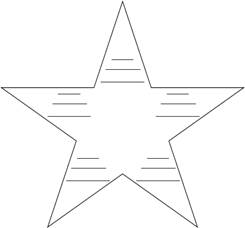

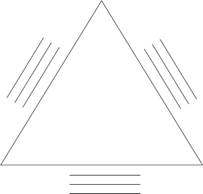

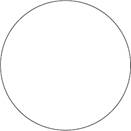

After reading: Shape Up Your Reading

The graphic organizer Shape Up Your Reading does just what it sounds like. It helps you size up or give shape to what it is you have read. Below, find a graphic organizer that my former teacher education student, Shannon Morris at Ball State University, and I created for you. You can modify or manipulate the directions for each shape as you wish. You can use just one shape or all four. You can use them in any order. For example, you can start with the square, the circle, or the star! You can write the information in the star, circle, and square as words, phrases, or entire sentences. For example, for the star, you can find one important idea or five. This is a super way to summarize and rethink what you read so you can keep it in your head. Complete the Shape Up Your Reading with the blog in this chapter titled “Building a Rainbow.”11

The Star

Write down the five most important ideas, topics, events, or themes from your reading in each star point.

The Triangle

Write down three supporting ideas from the reading on each leg that support a star point.

The Circle

Write down any recurring problem or question that keeps coming up in your reading. Wrap and write your question all the way around the circle.

The Square

On each side, write down any four background or building block pieces of information that might help solve the recurring problem or question. What do you know and what does the reading say about your question? Suggestion: Use your supporting ideas from the triangle to help you.

PAINLESS TIP

PAINLESS TIP

The Caricature of a Character and Shape Up Your Reading can be a lot of work, but when you write about something using your own words, and then you look for the author’s words, your brain automatically pays closer attention.

Wow! Using those organizers is fun, isn’t it? Did you notice the words you had to write about in the Word Write pop up more while you read the play? Were you looking for them? What does platonic mean, anyway? Your reading selections were not easy to read, but after you did all that, it should have been much easier.

Before, during, and after reading: SQ3R

The next reading selection is about math. Now, math and reading may sound like contradictory terms, but they aren’t! Math isn’t just numbers. In order to understand the numbers in math problems, you first need to read about them. In fact, reading math can be harder because you must read words, symbols, and numbers!

In every math lesson, there is a one- to two-page written explanation about that lesson. In every story problem, there are words, and you need to translate the words into numbers and the numbers into a problem. So, knowing how to read math is very important.

SURVEY:

Surveying is similar to skimming. Surveying requires you to get a sense of how the chapter or reading selection is set up prior to reading it. Read the title, any subheadings, the boldfaced words, the introduction, and the summary if there is one. Reading the summary first allows you to see where you are headed—the big ideas that can guide your reading.

QUESTION:

To question, use the question words Who, What, Where, When, Why, and How. Turn the chapter title and subheadings into questions using the question words. Then when you read, you can try to find the answers to the questions you created.

READ:

Then, read the selection. Read a section at a time. Take breaks in between if you need to

RECORD:.

Record your notes. While you are reading, answer the questions you created for the question section of SQ3R.

REVIEW:

Finally, review your notes. Reread your notes and make sure you understand what you read and write.

SQ3R is not only an effective way to read a difficult passage but also a super way to study for a quiz. Watching the teacher solve problems on greatest common factor and knowing how to solve them yourself is only half the equation. To really understand math concepts, you must understand the terms and the explanation of why and how such ideas like greatest common factor exist.

THE SQ3R METHOD

✵ Survey—Read the title, any subheadings, the boldfaced words, the introduction, and the summary if there is one.

✵ Question—Take the subtitles and words in boldfaced type and create questions using each of the question words.

— Who?

— What?

— Why?

— Where?

— When?

— How?

✵ Read the selection written by Deb Forkner.

✵ Record your notes—Write down answers to your questions above.

✵ Review your notes—Reread your questions and answers and maybe even re-solve the problems to make sure you understand.

YOUR ASSIGNMENT:

For the next reading selection on greatest common factors, you will be practicing SQ3R.

“Greatest Common Factor”

by Deb Forkner

Introduction: Definitions to Know

Look at each word: “greatest” means largest.

“Common” means something alike. If you and I have eye color in common, it means we both have brown eyes.

“Factor” means to multiply with another number to give the desired product. For example, the factors of 6 are 1, 2, 3, and 6. 1 × 6 = 6, 2 × 3 = 6. So, the GCF is the largest factor 2 numbers have alike.

Strategies for Finding the GCF: The List Method

One method for finding the GCF is the list method. If we want to find the GCF of 12 and 20, we would start by listing all the factors of 12 and listing all the factors of 20.

12: 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12

20: 1, 2, 4, 5, 10, 20

So, by examining the lists of factors you can see that 4 is the largest factor that is in both lists. So 4 is the largest factor that 12 and 20 have in common. 4 is the GCF of 12 and 20.

Strategies for Finding the GCF: Prime Factorization

Now, let’s use the same numbers, 12 and 20, but do the prime factorization method.

First, get the prime factorization of 12 and 20. Then we will compare their prime factors.

12 |

2× |

2× |

3 |

20 |

2× |

2× |

5 |

GCF = 2 × 2 = 4

Look carefully at the prime factorizations. Each has 2 • 2 = 4. So like the list method, we get the same GCF of 4.

Let’s try two more numbers and use the prime factorization method only.

Try finding the GCF of 42 and 105.

The prime factorization of 42 is 2 • 3 • 7.

The prime factorization of 105 is 3 • 5 • 7.

42 |

2× |

3× |

7 |

105 |

5× |

3× |

7 |

GCF = 3 × 7 = 21

They have in common a factor of 3 and a factor of 7.

So the product of the factors they have in common is 21; 21 is the GCF of 42 and 105.

Let’s Practice: Finding the GCF

Find the GCF of 25 and 32.

The prime factorization of 25 is 5 • 5.

The prime factorization of 32 is 2 • 2 • 2 • 2 • 2.

What factor(s) do 25 and 32 have in common? Before you answer, go back and list all the factors of 25 and 32:

25: 1, 5, 25

32: 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32

25 |

5× |

5 |

||||

32 |

2× |

2× |

2× |

2× |

2 |

GCF = 1

You can see from the lists of factors that 25 and 32 have a GCF of 1. When that occurs, the two numbers are called relatively prime. Neither number is prime, but when the greatest common factor is one, they are considered relatively prime numbers. One is a factor of all numbers.

Summary

GCF stands for greatest common factor. Remember that the GCF is the product of the common primes. Something that is prime is a positive integer that has exactly two positive integer factors, 1 and itself. If we list the factors of 24, we have 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24. That’s eight factors. If we list the factors of 11, we only have 1 and 11. That’s 2. So we say that 11 is a prime number, but 24 isn’t. There are two methods in finding the GCF, which are the List Method and Prime Factorization.

Reflect on what you have learned!

If you just sit down and don’t take the time to think about what you are going to read before you read it and keep your brain active while you are reading it, it’s hard to do anything after! Reading organizers may seem like a lot of work, but if you take the time to do them before and during reading, they make your homework easier once you have finished reading—and you actually understand what you read.

PAINLESS TIP

PAINLESS TIP

Which reading organizers work well for you? Which ones will you add to your toolbox? Make a list of types of organizers you enjoy working with and the ones you feel are most helpful.

BRAIN TICKLERSSet # 8

BRAIN TICKLERSSet # 8

Remember, to master the multiple-choice questions, use the strategies learned in Chapter Two!

1. When you use the vocabulary staircase, you assign words a face with a smile, a face with a frown, or a straight face based on the word’s connotation. What is the connotation of a word?

a. Part of speech

b. Dictionary definition

c. Definition you associate with the word

d. Denotation of a word

2. What is the point of using the Word Write and writing a paragraph and making up meanings for words you don’t know?

a. Seeing the words and using the words help your brain warm up to the words.

b. Seeing the words helps you to look them up in the dictionary.

c. Seeing the words helps you to write the paragraph.

d. Seeing the words helps you to explain the paragraph.

3. When you complete a Caricature of a Character, you write down not only what the character looks like but also what the character is thinking. What if the character doesn’t say anything about thinking or feeling? What do you do?

a. You leave it blank.

b. You guess.

c. You write down what you are feeling or thinking.

d. You infer what the character is thinking or feeling.

(Answers are on page 152.)