Pros and Cons - Debbie Newman, Ben Woolgar 2014

Introduction

How can Pros and Cons help you to debate?

To debate well you need:

1 to have a range of good arguments and rebuttals

2 to develop these in a clear, detailed and analytical way

3 to deliver them persuasively.

Pros and Cons can help you with the first, and only the first, of these three. If you were to read out one side of a pros and cons article, it would not fill even the shortest of debate speeches. Each point is designed to express the idea, but you will need to flesh it out. If you know your topic in advance, you will be able to use these points as a springboard for your own research. If you are in an impromptu debate, you will have to rely on your own knowledge and ideas to populate the argument with up-to-date examples, detailed analysis and vivid analogies. But the ideas themselves can be useful. It is hard to know something about everything and yet debating competitions expect you to. It is important to read widely and follow current affairs, but doing that does not guarantee that you will not get caught out by a debate on indigenous languages, nuclear energy or taxation. Pros and Cons can be a useful safety net in those situations.

When using each article it is worth considering:

A Does each point stand up as a constructive argument in its own right, or is it only really strong as a rebuttal to its equivalent point on the other side? Where there are key points which directly clash, they have been placed opposite each other, but some points have been used to counter an argument rather than as a positive reason for one side of the case.

B Can the points be merged or split? Different debate formats favour different numbers of arguments. Check to see if two of the points here could be joined into a larger point. Or if you need quantity, sub-points could be repackaged as distinct arguments. If you are delivering an extension in a World Universities-style debate (or a British Parliament-style one), it is worth noting down the sub-points. It is possible that the top half of the table may make an economic argument, but have they hit all three of the smaller economic points? If they have not, then one of these, correctly labelled, could form your main extension.

C Look at Pros and Cons last, not first. Try to brainstorm your own arguments first and then check the chapter to see if there is anything there you had not thought of. The articles are not comprehensive and often not surprising (especially if the other teams also have the book!), so it is best not to rely on it too heavily. Also, if you do not practise generating points yourself, what will you do when the motion announced is not in here?

D Adapt the arguments here to the jurisdiction in which you are debating. The book is designed to be more international than its predecessor, but the writers are British and that bias will come through. The debate within your own country may have its own intricacies which are not reflected in the broader global debate. Some arguments are based on assumptions of liberal democracy and other values and systems which may just be plain wrong where you live.

E Is the argument or the example out of date? We have tried to write broad arguments which will stand the test of time, but the world changes. Do not believe everything you read here if you know or suspect it to be untrue! Things like whether something is legal or illegal in a given country change very quickly, so please do your research.

F What is the most effective order of arguments? This book lists points, but that is not the same as a debating case. You will need to think about how to order arguments, how to divide them between speakers, and how to label them as well as how much time to give to each. On the opposition in particular, some of the most significant points could be towards the end of the list.

Debating formats

There is an almost bewildering number of debate formats across the world. The number of speakers, the length and order of speeches, the role of the audience and opportunities for interruption and questioning all vary. So too do the judging criteria. On one side of the spectrum, some formats place so much emphasis on content and strategy that the debaters speak faster than most people can follow. On the other side, persuasive rhetoric and witty repartee can be valued more than logical analysis and examples. Most debate formats sit in the middle of this divide and give credit for content, style and strategy. Here are a few debate formats used in the English-Speaking Union programmes:

Mace format

This format involves two teams with two speakers on each side. Each speaker delivers a seven-minute speech and there is then a floor debate, where members of the audience make brief points, before one speaker on each team delivers a four-minute summary speech with the opposition team speaking first. The order is as follows:

First Proposition Speaker

First Opposition Speaker

Second Proposition Speaker

Second Opposition Speaker

Floor Debate

Opposition Summary Speaker

Proposition Summary Speaker

The first Proposition Speaker should define the debate. This does not mean giving dictionary definitions of every word, but rather explaining the terms so that everybody is clear exactly what the debate is about. For example, the speaker may need to clarify whether the law which is being debated should be passed just in their country or all around the world and specify any exemptions or limits. This speaker should then outline their side’s arguments and go through the first, usually two or three, points in detail.

The first Opposition speaker should clarify the Opposition position in the debate; e.g. are they putting forward a counter-proposal or supporting the status quo? They should then outline their side’s case, rebut the arguments put forward by the first Proposition Speaker and explain their team’s first few arguments.

The second speakers on both sides should rebut the arguments which have come from the other team, support the points put forward by their first speakers, if they have been attacked, and then add at least one completely new point to the debate. It is not enough simply to expand on the arguments of the first speaker.

The summary speakers must remind the audience of the key points in the debate and try to convince them that they have been more persuasive in these areas than their opponents. The summary speakers should respond to points from the floor debate (and in the case of the Proposition team, to the second Opposition speech), but they should not add any new arguments to the debate at this stage.

Points of information

In this format, points of information (POIs) are allowed during the first four speeches but not in the summary speeches. The first and last minute of speeches are protected from these and a timekeeper should make an audible signal such as a bell ringing or a knock after one minute and at six minutes, as well as two at the end of the speech to indicate that the time is up. To offer point of information to the other team, a speaker should stand up and say ’on a point of information’ or ’on that point’. They must then wait to see if the speaker who is delivering their speech will say ’accepted’ or ’declined’.

If declined, the offerer must sit down and try again later. If accepted, they make a short point and then must sit down again and allow the main speaker to answer the point and carry on with their speech. All speakers should offer points of information, but should be sensitive not to offer so many that they are seen as barracking the speaker who has the floor. A speaker is recommended to take two points of information during a seven- minute speech and will be rewarded for accepting and answering these points.

Rebuttal

Apart from the very first speech in the debate, all speakers are expected to rebut the points which have come before them from the opposing team. This means listening to what the speaker has said and then explaining in your speech why their points are wrong, irrelevant, insignificant, dangerous, immoral, contradictory, or adducing any other grounds on which they can be undermined. It is not simply putting forward arguments against the motion — this is the constructive material — it is countering the specific arguments which have been put forward. As a speaker, you can think before the debate about what points may come up and prepare rebuttals to them, but be careful not to pre-empt arguments (the other side may not have thought of them) and make sure you listen carefully and rebut what the speaker actually says, not what you thought they would. However much you prepare, you will have to think on your feet.

The mace format awards points equally in four categories: reasoning and evidence, listening and responding, expression and delivery, and organisation and prioritisation.

LDC format

The LDC format was devised for the London Debate Challenge and is now widely used with younger students and for classroom debating at all levels. It has two teams of three speakers each of whom speaks for five minutes (or three or four with younger or novice debaters).

For the order of speeches, the rules on points of information and the judging criteria, please see the section on the mace format’. The only differences are the shorter (and equal) length of speeches and the fact that the summary speech is delivered by a third speaker rather than by a speaker who has already delivered a main speech. This allows more speakers to be involved.

World Schools Debating Championships (WSDC) style

This format is used at the World Schools Debating Championships and is also commonly used in the domestic circuits of many countries around the world. It consists of two teams of three speakers all of whom deliver a main eight-minute speech. One speaker also delivers a four-minute reply speech. There is no floor debate. The order is as follows:

First Proposition Speaker

First Opposition Speaker

Second Proposition Speaker

Second Opposition Speaker

Third Proposition Speaker

Third Opposition Speaker

Opposition Reply Speech

Proposition Reply Speech

For the roles of the first two speakers on each side, see the section on ’the mace format’, above. The WSDC format also has a third main speech:

Third speakers

Third speakers on both sides need to address the arguments and the rebuttals put forward by the opposing team. Their aim should be to strengthen the arguments their team mates have put forward, weaken the Opposition and show why their case is still standing at the end of the debate. The rules allow the third Proposition, but not the third Opposition speaker to add a small point of their own, but in practice, many teams prefer to spend the time on rebuttal. Both speakers will certainly want to add new analysis and possibly new examples to reinforce their case.

Reply speakers

The reply speeches are a chance to reflect on the debate, albeit in a biased way. The speaker should package what has happened in the debate in such a way as to convince the audience, and the judges, that in the three main speeches, their side of the debate came through as the more persuasive. It should not contain new material, with the exception that the Proposition reply speech may need some new rebuttal after the third Opposition speech.

Points of information are allowed in this format in the three main speeches, but not in the reply speeches. The first and last minute of the main speeches are protected. For more information on points of information, see the section on ’ the mace format’.

The judging criteria for the WSDC format is 40 per cent content, 40 per cent style and 20 per cent strategy.

The main features of the format as practised at the World Schools Debating Championships are:

✵ The debate should be approached from a global perspective. The definition should be global with only necessary exceptions. The examples should be global. The arguments should consider how the debate may be different in countries that are, for example, more or less economically developed or more or less democratic.

✵ The motions should be debated at the level of generality in which they have been worded. In some formats, it is acceptable to narrow down a motion to one example of the principle, but at WSDC, you are expected to give multiple examples of a wide topic if it is phrased widely.

✵ The WSDC format gives 40 per cent of its marks to style which is more than many domestic circuits. This means that speakers should slow down (if they are used to racing), think about their language choice and make an effort to be engaging in their delivery.

World Universities/British Parliamentary style

This format is quite different to the three described so far. It is one of the most commonly used formats at university level (the World Universities Debating Championships use it), and it is widely used in schools’ competitions hosted by universities in the UK.

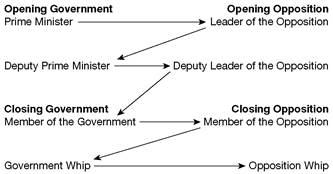

It consists of four teams of two: two teams on each side of the motion. The teams on the same side must agree with each other, but debate better than the other teams on the same side in order to win. The teams do not prepare together. At university level, speeches are usually seven minutes long, whereas at school level, they are commonly five minutes. Points of information are allowed in all eight speeches and the first and last minute of each speech is protected from them (for more on points of information, see the section on ’the mace format’. The speeches are often given parliamentary names and the order of speeches is as follows:

The speaking order in the World Universities or British Parliamentary debate format.

For the roles of the first two speakers on both sides, see the section on ’the mace format’.

The roles of the closing teams are as follows:

Members of the government (third speakers on each side)

The third speaker should do substantial rebuttal to what has come before them in the debate if needed. They are also required to move the debate forward with at least one

new argument which is sometimes called an ’extension’. The closing team should not contradict the opening team, but neither can they simply repeat their arguments, having had more time to think about how to put them persuasively.

Whips (fourth speakers on each side)

The whips deliver summary speeches. They should not offer new arguments, but they can (and should) offer new rebuttal and analysis as they synthesise the debate. They should summarise all the key points on their team and try to emphasise why their partner’s contribution has been particularly significant.

Debating in the classroom

Teachers should use or invent any format which suits their lessons. Speech length and the number of speakers can vary, as long as they are equal on both sides. The LDC format explained here is often an effective one in the classroom. Points of information can be used or discarded as wanted and the floor debate could be replaced with a question and answer session. Students can be used as the chairperson and timekeeper and the rest of the class can be involved through the floor debate and audience vote. If more class participation is needed, then students could be given peer assessment sheets to fill in as the debate goes on, or they could be journalists who will have to write up an article on the debate for homework.

In the language classroom or with younger pupils, teachers may be free to pick any topic, as the point of the exercise will be to develop the students’ speaking and listening skills. Debates, however, can also be a useful teaching tool for delivering content and understanding across the curriculum. Science classrooms could host debates on genetics or nuclear energy; literature lessons can be enhanced with textual debates; geography teachers could choose topics on the environment or globalisation. When assessing the debate, the teacher will need to decide how much, if any, emphasis they are giving to the debating skills of the student and how much to the knowledge and understanding of the topic shown.

In addition to full-length debates, teachers may find it useful to use the topics in this book (and others they generate) for ’hat’ debates. Write topics out and put them in a hat. Choose two students and invite them to pick out a topic which they then speak on for a minute each. Or for a variation, let them play ’rebuttal tennis’ where they knock points back and forth to each other. This can be a good way to get large numbers of students speaking and can be an engaging starter activity, to introduce a new topic or to review student learning.