The word snoop - Ursula Dubosarsky 2009

Punctuation: Do we need it?

Dots and dashes, interrobangs and cat’s claws

The funny thing about punctuation is that it’s actually not that hard to read without it, once you get used to it. Think of when you and a friend are texting—you hardly use any regular punctuation, but you can still understand each other. And in the Thai language, for example, there are rarely spaces between words and very few punctuation marks, but people keep reading anyway. After all, if you’re not expecting to see something, you don’t go looking for it.

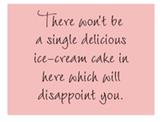

Still, it’s certainly true that punctuation can sometimes help make the meaning of something clearer. The Word Snoop remembers the time she came home from school, and found this note left on the fridge door by her auntie:

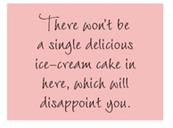

Yum! I thought, picturing all those undisappointingly delicious ice-cream cakes inside. But when I opened the fridge door, I realized that my auntie actually meant:

Hmmph! I should’ve written under the note, I’m so disappointed I want to eat Auntie. Oops, I mean, I’m so disappointed. I want to eat, Auntie!

But luckily this kind of confusion happens far less often than you might think. And sometimes, when it does happen, it could be that the writer meant both things anyway—after all, writers just love double meanings and puns.

In the end, as with most things to do with language, writers will make different choices about punctuation because they think differently about sentences and words. It’s part of the personality of their writing. William Shakespeare, for example, used almost eight times as many colons : in his seventeenth-century plays as we would nowadays, and in the eighteenth century, novelist Jane Austen used exclamation marks ! far more often than her fellow novelist Daniel Defoe. In the nineteenth century, Swedish playwright Henrik Ibsen used four times as many dashes — as the Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw. Then in the twentieth century, dramatist John Galsworthy used four times as many semicolons ; as playwright Eugene O’Neill.

So, as you can imagine, writers and editors, students and teachers can spend a lot of time arguing about punctuation, because sometimes there’s no “right” answer. The nineteenth-century Irish writer Oscar Wilde once reported that: “I was working on one of my poems all the morning, and took out a comma. In the afternoon I put it back again.” (But what happened the day after that?)

Some writers HATE punctuation. The eighteenth-century American entrepreneur Timothy Dexter hated it so much that he included a separate page of periods and commas in a booklet he published. He said that readers who needed them were welcome to sprinkle them about wherever they wanted, like salt and pepper, but he wasn’t going to put them in himself.

Then again, other writers LOVE punctuation. The seventeenth-century English writer Ben Jonson loved punctuation so much, he even added a colon between his first and last names—Ben:Jonson. (Nobody has ever figured out why exactly . . .) And when the noble German poet Goethe lay dying in 1832, he was seen to trace out words with his fingers, being very careful to include the correct punctuation marks.

It’s hard to know whether Irishman James Joyce loved or hated punctuation. There is a whole chapter in his novel Ulysses with almost no punctuation at all, except right at the very end where he put—you guessed it—a period.

Whether you love or hate punctuation, maybe the best advice is just to enjoy it. It can even make you laugh. The Danish entertainer Victor Borge did a very funny comedy sketch called “Phonetic Punctuation,” where he made up a different wacky sound for each punctuation mark—for an em-dash, a colon, an exclamation mark, and so on. See if you can track down a recording of it (on the Internet, perhaps?).

I have to confess that I love punctuation. I love everything about it, even when people tell me I’ve got it all wrong! It would make me very sad if punctuation disappeared from our sentences. After all, punctuation has been around for more than a thousand years—the page would look undressed without it. Enjoy it, play with it, think about it, use it. It belongs to the language, and it belongs to you.

Happy punctuating!

! or ?

If you think about it, a single punctuation mark can carry a lot of meaning. Have you ever seen the episode of the TV sitcom Seinfeld, where one of the characters, Elaine, gets extremely upset with a friend who writes down a phone message and fails to add an exclamation mark at the end? And I bet you’ve sent an e-mail or text message with just a ! or a ? once in a while. Actually, back in the nineteenth century, long before texting was even thought of, the French writer Victor Hugo was worried about whether anyone would like his new novel, Les Miserables. He is said to have sent a message to his publisher containing only one thing, a question mark: ? The publisher sent him back a note with a single exclamation mark: !

Hey Word Snoops, over here! How did you do with the last code? See if you can crack this one I made up using my keyboard.

(Hint: ’*% ;}%!_. ?[”$ ;{}}[ = The sneaky Word Snoop)