The word snoop - Ursula Dubosarsky 2009

The invention of printing

Why is english so strange?

What happened was something that truly CHANGED THE WORLD. It was a technological invention from Germany, which was just as amazing as the invention of the television or computers or the Internet.

This invention was—wait for it—the printing press! Now, while types of fixed printing, called block printing or stamping, had already been used in China for centuries, the mechanized printing press, with letters that could be moved around, was a brand-new invention that changed everything. Why? Well, believe it or not, until then all books in Europe had to be copied out by hand—usually by monks. It took ages just to make a single book, so there weren’t many books around. People traveled for miles, even to different countries, just to read a book that was kept in a particular library.

But when Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press in 1440, it meant that machines could print onto paper over and over again, and then the paper could be bound into books. By the end of the fifteenth century, there were thousands of books in print all over Europe. (Those lucky monks could heave a big sigh, put their pens down, and have a nice bath instead!)

In England, a printing press was set up in 1476 by a man called William Caxton. Although people spoke and spelled English differently all over the country, Caxton decided to print books in the type of English that people used in the biggest city—London. This is the kind of English that we now call Modern English, and it’s basically what we speak and write—and spell—today.

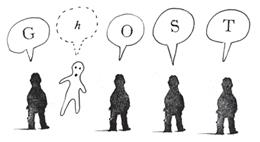

Printing was very important for spelling, because the decision of how to spell words was left largely to the people running the printing press (just as before it had been left largely to the monks who copied the books out). The problem was that quite a lot of the printers were from Europe, and English was not their first language. So, even if they were good spellers, it was easy for them to make mistakes. ( Just imagine us Word Snoops trying to decide how to spell something in Spanish, por ejemplo. I mean, for example!) This is thought to be the reason for the silent letter in the word ghost, which was originally spelled without an h. Printers from Holland put the h in, because that’s how they spelled it in their language.

But that was just one complication. Printers also affected spelling because they wanted printed pages to look nice and neat, with all the lines ending at the same place. (This is called justifying—you might have seen this option on the computer.) In order to make printed lines longer or shorter, sometimes printers would decide to add an extra letter (an e, for example), or leave one off. This happened especially with what you might call unnecessary letters—such as the k, which used to be put at the ends of words like music(musick) and logic(logick).

Now, once something’s printed out, it can be hard to change. This was especially true back in the days when printing began, as one of the most popular books in print was the Bible. The printers felt very nervous about changing anything in the Bible, even if it didn’t look quite right.

Even more importantly, there was still no such thing as a standard dictionary with agreed “correct” spellings that the printers could look up to check a word as we would today. And let’s face it, in the old days they didn’t have quite the same idea of correct spelling as we do, anyway. The poet Geoffrey Chaucer, who wrote the famous Canterbury Tales in the fourteenth century, even seemed to have spelled a similar word two different ways in one sentence! See if you can spot it.

Nowher so besy a man as he . . . And yet

he semed bisier than he was.

But the arrival of printing meant that people became more interested in the idea of standard spelling and how a word should be written. They realized it would make life much easier for everyone if the spelling of a word was always the same.

This led to the beginnings of English dictionaries. The most famous and fascinating of the early English dictionaries was that of Dr. Samuel Johnson, published in 1755. Dr. Johnson loved the English language so much that he wanted to make sure its wonderful words would be looked after properly. He read thousands and thousands of books, letters, poems, and plays—and more—to find what he thought was the best spelling and meaning for a word.

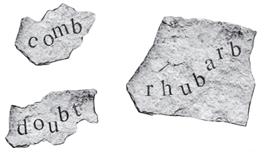

So, next time you read a sentence, you’ll realize you’re seeing something very special. It may be that the word is spelled how it was pronounced hundreds of years ago, or according to a fashion, or just by mistake or confusion, or because somebody liked it like that. But all of those amazing spellings have been preserved, even frozen in the language, like fossils trapped in amber . . .