Practical models for technical communication - Shannon Kelley 2021

Steps for research

Research methods for technical communication

As in Jessamyn’s scenario, you need to determine what problem needs solving. Sometimes this is easy: you receive an assignment from your boss or instructor. The assignment has a clear outcome, such as “determine the feasibility of switching to electric vehicles.”

In your case, you may get an open-ended research project from your instructor. Your instructor may assign you a topic or give you the option to decide what you want to research and why. In your professional life, you can expect to encounter any combination of reasons to do research that range from bidding on a work contract to submitting a business plan to qualify for a small business loan. Doing effective, honest, ethical research is a part of everyday life in the professional world.

Step One: Observe the Problem

To begin the research process, you need to spend some time observing the problem. For the purposes of illustration, let’s say your problem is that you’re waking up exhausted. During this stage of research, you begin by making observations and collecting data about your energy levels. Are there certain days you’re more tired than others? Does it correspond to the number of hours you slept or to the amount of caffeine you did or did not consume? Do you notice that you’re more tired on the mornings you don’t eat breakfast? Does the room’s temperature affect your sleep quality? Are you more or less tired when you exercise the day before? What about screen time? Do you get better sleep when you turn off all screens an hour before bedtime? Do you even have a bedtime?

As you collect your data points, look for patterns, trends, correlations, or changes that can lead you toward the formulation of a more precise research question. Determining research questions can help guide your research.

Step Two: Form a Question

To refine your research, you need to come up with a specific question. You could ask yourself, “Why am I so exhausted?” but you’re unlikely to find research that will be able to provide a suitable answer. Effective research requires an appropriate level of focus. You will need to narrow your question to one of the data points you observed earlier. Let’s say that you noticed you woke up multiple times during the night because you were too hot. You can narrow your focus by pairing your original idea (sleep quality) with a more specific subtopic (room temperature). A researchable question might then be, “What is the ideal temperature for better-quality sleep?” The process of defining a narrow, researchable question will keep you from getting distracted by too many possibilities.

Step Three: Propose an Answer

Those of you familiar with the scientific method probably see where we’re going with this. You need to form a hypothesis, an educated guess that will then be tested. At this stage, you come up with an answer to your research question based on what you may already know or think you know about the issue you’re researching. Your experience of tossing and turning at night suggests that room temperature plays a part in sleep quality. Your hypothesis, then, is this: “Cooler room temperatures contribute to better sleep quality.” The value of a hypothesis is that it tells you what you are and, more importantly, are not researching.

Step Four: Test the Hypothesis

This step is the biggest difference between academic research and research in technical communication. In technical fields, the purpose of research is to test the hypothesis. Your goal isn’t to prove you are right. Instead, the goal is to determine whether the proposed answer is supported by evidence. To test your hypothesis about cooler room temperatures, you could turn down your thermostat and keep a record of your sleep quality over the course of several weeks. Better yet, you can find a researcher who has already tested this hypothesis on a larger group of test subjects and published the results in a peer-reviewed journal.

In your search for a better night’s sleep, your preliminary research may lead you to change your hypothesis. Maybe sleep quality is equally impacted by the room’s temperature and the amount of artificial light in the room. In this scenario, you may find that you get better results if your research explores two factors rather than one.

Step Five: Draw Conclusions

The next two steps of the research process require discipline. Many of us don’t like being wrong, which can lead to questionable choices during the research process. As in all areas of communication, honesty is the best policy. If you manipulate or exaggerate your results, you may have to deal with serious consequences.

If your hypothesis doesn’t work out, simply say so and suggest an alternative solution or new research angle. The user will then act based on your well-informed advice.

Preliminary Research

Dividing research into two stages can save time. The first stage is preliminary research, which you use to accomplish the following:

” Find useful search terms. Take time to learn how professionals in the field refer to what you’re looking for. This is one of the better uses for sites like Wikipedia—you can scroll through and look for terms that might get better search results. For instance, the more common term for myocardial infarction is heart attack. If you’re looking for recent medical research on heart attacks using the search term “heart attack,” you will get limited results. You have to figure out how experts in the field talk about the topic. Create a list of key terms.

” Take your research to the next level. It’s rare to come up with a research project that hasn’t already been explored on some level. If you find yourself at a loss for sources, it probably has more to do with what’s going into the search bar than a lack of existing research covering the topic. If this is the case, seek the help of a reference librarian. Most reference librarians staff 24-7 chat sessions, have direct lines, or respond to emails. You can find this feature by going to your library’s homepage.

” Collect possible sources. Since most topics have already been researched by someone else, you can use this preliminary stage to collect the material you want to examine more closely. Use credible sources that list the references they used.

Chances are you will read more than what you directly reference in your report. Jessamyn will collect information about the problem of gasoline vehicles and potential solutions of EVs so she can attain a level of expertise on the topic. That means she will read all types of articles, trade journals, and scholarly sources to inform her recommendation.

Preliminary research involves a lot of skimming. You can find tips for skimming documents later in this chapter. This stage involves concentrating on secondary sources and determining whether you will need to do any field work.

Final Research

The final research stage is where you do a deep dive. Effective research is like increasing the power on a microscope to see the details of your project better. You’ll need to have a solid grasp of the big picture alongside the granular details because you’ll probably be tasked with explaining your findings when necessary. If your document is longer, like a technical research report, part of the document will show the granular details you discovered through your research.

As you develop your research, you will most likely encounter new questions, new answers, and further research. This is where having a focused question and clear hypothesis comes in handy: it organizes your research according to relevance.

Step Six: Narrow the Research Topic

Let’s revisit the sleep-quality scenario and imagine that you are waking up tired every day. This may or may not be a technical issue, but it provides some background for a possible technical research topic.

First, you need to observe the pattern and eliminate multiple possibilities. Your bedroom temperature runs hot in the summer and cold in the winter. This variation doesn’t affect your sleep quality. Beyond your first-hand experience, your preliminary research on room temperature and artificial light didn’t produce useful results.

Your next step is to narrow your topic. The common factor in all your sleepless nights has been your old mattress—the one you’ve been sleeping on for most of your adult life. Now you have a somewhat technical research question: “What mattress will give me the best rest for my money?”

This topic triangle can help you see how to narrow your topic as you conduct research (figure 5.1). The scope and focus of your research may change as you start making progress. Simple problems get simple solutions—now you’re on to a much more complicated topic: choosing a good mattress.

Figure 5.1. From General to Specific Research Topic. Effective research requires narrowing down to a specific topic to produce a focused search.

Step Seven: Locate Credible Sources

If you’re reading this textbook because you’re in college, you are in luck: a chunk of your tuition pays for access to credible resources and library databases to use for research. In short, you probably have access to independent sleep and mattress studies through the college library’s catalog. If Jessamyn still had access her college’s database to find recent research on EVs, it would make her research a lot easier. After you’ve narrowed your topic, you can take advantage of these academic resources to find the studies you need to make your final assessment.

See your college library’s website for more about reference librarians and research assistance.

Reference librarians are another resource you can use to find relevant material. Sometimes jokingly referred to as “the original search engine,” reference librarians offer much more than a Google search. They can advise you on anything from search techniques to citation methods. They can help you ensure your report on mattresses is the best, most comprehensive mattress report ever.

If you, like Jessamyn, are using a regular internet search, you should limit your search to weed out false results. A basic Google search algorithm privileges paid advertising (usually marked) and so-called relevant search results, which are governed by how frequently the sites are linked or clicked. To get on the top results lists, some businesses buy clicks.1

Save time with these three ways to restrict your internet search:

” Do most of your searches using Google Scholar (figure 5.2).

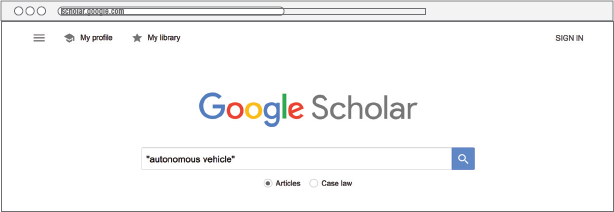

” Use quotation marks around your search phrases to restrict the search to that exact word combination (figure 5.3).

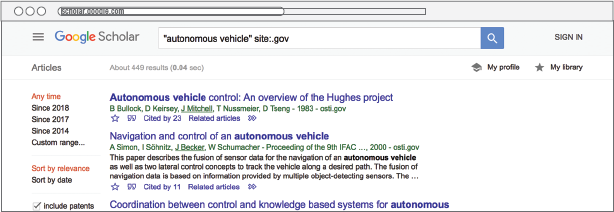

” Restrict your search to .gov or .edu sites to find independently conducted research by using the “site:” function (figure 5.4).

You can also use the “site:” function in a standard Google search to narrow your results to more relevant sources. Even when you take this step, you still need to determine the relevance, accuracy, and credibility of your search results. Don’t simply use whatever you find on your first try—dig a little deeper. If you use all these tools to locate sources and come up short, you may need to conduct primary research.

Figure 5.2. Using Google Scholar. Google Scholar compiles resources from academic literature, such as journals, university publishers, and other sites it identifies as scholarly.

Figure 5.3. Conducting Effective Online Searches. The quotation marks tell Google to search for these words as a distinct unit.

Figure 5.4. Locating Educational and Goverment Websties. Websites with a domain of .edu are linked to educational institutions. Websites with a domain of .gov are linked to government institutions. This search limits the sites to those produced by government agencies.

Step Eight: Skim for Relevant Information

When you find a source, evaluate it quickly to determine its relevance or usefulness. Get curious by asking yourself the following questions:

” Who wrote it?

” What can you learn about the source?

” When and where was it published?

” Does the source provide references?

Take notes as you research so you don’t lose the source or your impressions of it as you make your evaluation. If you aren’t taking notes, you aren’t retaining information. Studies show that handwritten notes help you retain information better than taking notes on your phone or a laptop.2

Tips for Skimming

When you skim your document, evaluate the source first. We cover this process of evaluating sources later in this chapter. Where possible, take the following steps to skim documents:

” Read the abstract, if any.

” Look for the scope of the research and methods, and review the sources at the end of the document.

” Read enough of the introduction and the conclusion to determine the reasons and outcomes for the document.

” Determine whether the source uses language you can’t understand, such as jargon or formulas you haven’t learned to interpret.

Tips for Taking Notes

There’s a saying that the weakest ink is better than the strongest memory. This is why you should take notes whenever you do research. It can save you time and effort to jot down even a few key terms while working through your sources.

Whatever note-taking style you use is up to you, but follow these fundamentals while doing research:

” Make sure you can find the source again. Make a bibliography as you find sources instead of waiting until the end of your project. Keep track of important information (author, title, place of publication) that may get lost otherwise. At minimum, write this information down in your research notes.

” Write down keywords you may need to look up. You’ll need to hit the dictionary a lot more when you use peer-reviewed or scholarly articles. Write down any thoughts you have about the research materials, such as how the source is relevant to your research. This can be part of your screening technique for sorting material quickly.

” Record useful statistics and data you’ll use. Jot down a quick note reminding yourself why you chose the information.

” Save page numbers. This is particularly important if you’re using a citation style that requires them.

Don’t underestimate the power of note-taking. Effective note-taking requires diligence, but ultimately notes save you time and effort as you compile research for your technical document. You will reference your research often as you compile a report and will be thankful for clearly written notes.