Practical models for technical communication - Shannon Kelley 2021

Typical elements of proposals

Proposals and short reports

Proposals tend to follow a similar structure, which typically includes several (if not all) of the following sections.

Summary

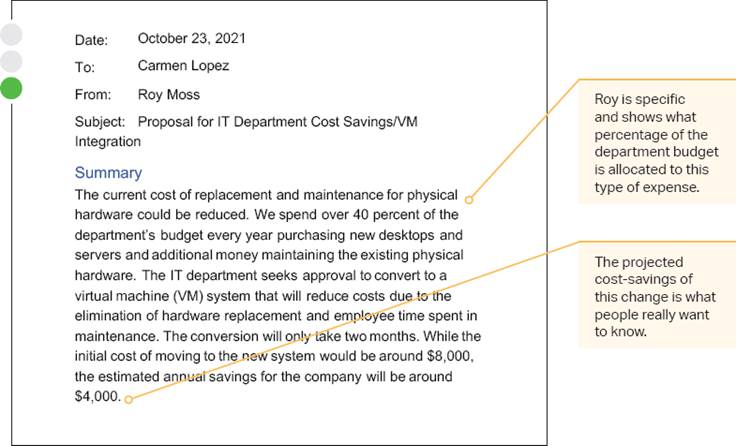

A shorter proposal might not need a summary, but longer proposals of more than a few pages will. Summaries are also called executive summaries or abstracts in some cases. Often this section is included on the title page, and sometimes it is limited to a specific word count. The summary’s purpose is to provide a quick rundown of the proposal, as you can see here with Roy’s summary (figure 10.5).

In some cases, a user may review only the summary before deciding if they want to read the entire proposal. As a result, it’s wise to think of a summary as a short sales pitch.

When writing a proposal summary, present the key information in an abbreviated format. This section should briefly and clearly state the proposal’s problem and provide a brief overview of your recommendation. If the decision-makers find something useful in the summary, they’ll have a reason to keep reading. The abstracts at the beginning of each chapter in this textbook function in a similar way.

Figure 10.5. Proposal Summary. This model shows the opening of Roy’s proposal to his boss.

Introduction

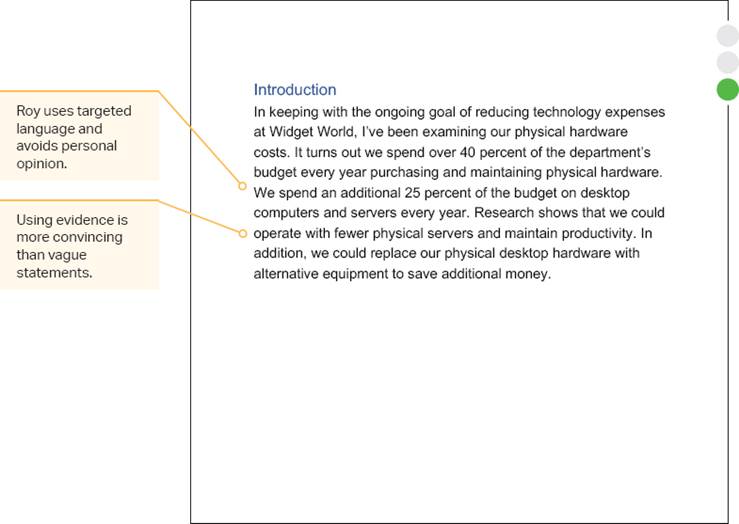

The introduction sets the stage for the body of the proposal. It’s where you provide background, an overview of key ideas in the proposal, and a preview of the document’s organization.

The introduction is different from a summary. While the summary condenses the entire proposal into a smaller package, an introduction smoothly leads into the main content of the document. In Roy’s introduction, he links his proposal with the company’s “ongoing goal of reducing technology expenses” in order to show how this idea aligns with other priorities (figure 10.6).

Figure 10.6. Proposal Introduction. This model shows the introduction of Roy’s proposal to his boss.

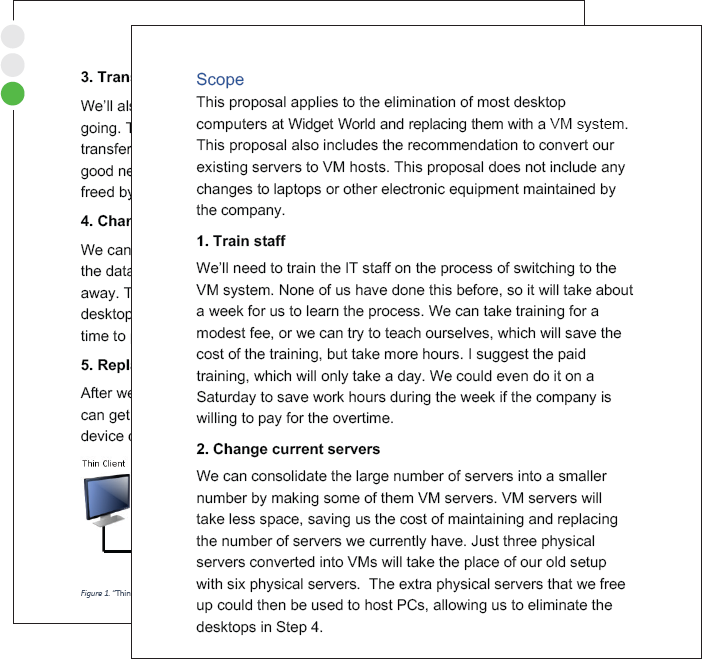

Scope

The scope of a proposal explains the suggested course of action. It is the heart of the proposal. In this section, you must provide convincing evidence that your recommendation is the best choice. Your evidence comes from talking to experts, consulting appropriate sources, and possibly doing original research or experimentation. This section is sometimes referred to as a proposed program or a plan of work. As you can see in figure 10.7, Roy’s scope includes multiple steps.

See Chapter 5 for more on primary and secondary sources.

Figure 10.7. Proposal Scope. This model shows the scope of Roy’s proposal.

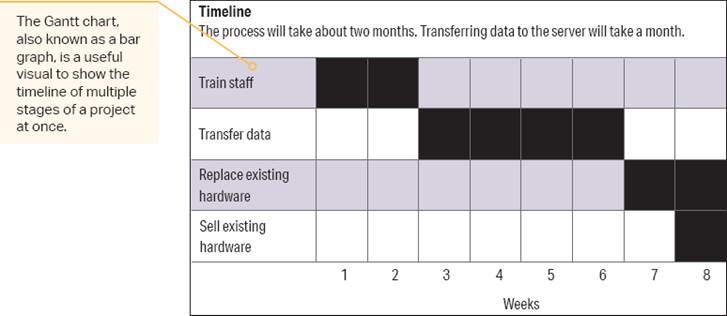

Timetable

A well-researched time frame gives the audience a realistic sense of how long the project will take. This section is important for decision-makers. An accurate timetable that is easy to interpret will make your proposal more valuable. Roy uses a Gantt chart to help his boss see the various stages of this project (figure 10.8).

Gantt charts are used to chart out tasks and timelines in collaborative projects where multiple assignments need to be completed at different times to achieve a specific outcome. The chart defines expectations and timelines, which keeps the team accountable and efficient.

Figure 10.8. Project Timeline. This model shows the timeline of Roy’s proposal to his boss using a Gantt chart.

Qualifications and Experience

This section of your proposal outlines your qualifications and experience to convince the audience that you have a reasonable plan for solving the problem. Making a clear proposal backed by solid research is a crucial part of showing that you have the ability to carry out the proposal successfully.

To begin, ask yourself if you have specialized knowledge or skills that make you the ideal candidate for this work. If so, state your experience explicitly. For example, Roy has a track record of problem solving in his department. He is also an expert in his field. If part of the plan involves experts in other areas, say so. The more transparent your proposal is, the better chance it has of being approved.

Budget

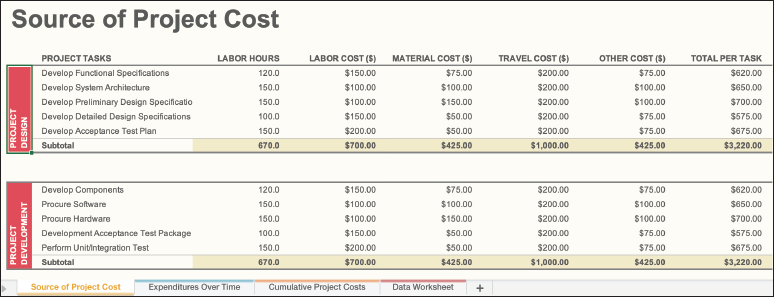

Decision-makers care about the cost of undertaking new projects. The budget section needs to provide realistic expense estimates (figure 10.9). As always, the numbers you use here need to be based on accurate research. Roy gathers quotes from other companies so he can provide associated costs of current and new systems. He also includes associated implementation costs to get a true idea of what the plan will cost the company.

Figure 10.9. Proposal Budget. Proposals should include any potential costs. This model shows Roy’s project estimates.

Conclusion

A conclusion smoothly brings the document to an end with a clear transition and a strong final statement. Be sure to review the purpose of the proposal. In other words, remind the audience of what you are asking them to approve. Always recap the main points of the proposal in a short format. Leave the audience with something to think about in your closing statement that highlights the lasting benefits of the proposed solution.

Appendixes

This section isn’t mandatory, but it is common in many proposals and reports. An appendix collects additional information at the end of a proposal or report and may include raw data, calculations, graphs, and other materials that were part of the research but not essential to the proposal itself. For proposals and other short reports with a lot of background information, there may be more than one appendix. Refer to each appendix at the appropriate point (or points) in the body of your proposal by inserting a parenthetical citation with the relevant appendix at the end of the sentence. If you have more than one appendix, assign each appendix a capital letter, as in Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C, etc.