Practical models for technical communication - Shannon Kelley 2021

Types of formal reports

Formal reports

Formal reports take different forms depending on their purpose, but all require some kind of analysis. Analysis means to look at how the individual parts of a complex process or product work together. For example, chemists regularly perform analysis on substances to identify their makeup on a molecular level.

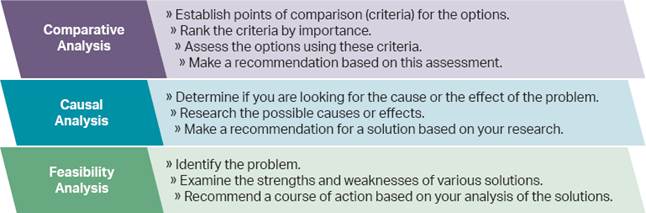

As a technical communicator, your analysis will focus on how complex ideas or situations are made up of more specific components. Most technical analysis includes a certain amount of informed speculation about causes and future possibilities as well. Formal reports almost always include analysis, which is why the three varieties explored here have “analysis” in their name. Refer to this table for a quick overview of common analytical reports (figure 11.2).

Figure 11.2. Types of Analysis. Use this table as a quick reference for the three main types of analytical reports described in this chapter.

Comparative Analysis

A comparative analysis is a formal report that establishes a set of criteria to look at similar items or situations to determine the best choice. Businesses often need a comparative analysis when considering a large purchase. For example, if a business wishes to expand to an overseas market but can’t decide between two specific locations, it might request a comparative analysis. Or consider an organization that wants better healthcare coverage for its employees. In this case, a comparative analysis could weigh the options and help the organization make the best choice.

If Jessamyn conducts a comparative analysis, she will need to determine how to compare the cars in the company’s current fleet to potential AV. Jessamyn must establish points of comparison up-front so that the different vehicle types are compared fairly and consistently. She will likely compare the cost of purchase or replacement, fuel, insurance, maintenance, and labor. She’ll determine how much revenue each vehicle generates (or is estimated to generate) and its reliability. Then, in the report, she will clearly explain the criteria she used in the methodology section. In her report, she will rank the cars according to the criteria, assess their strengths and weaknesses, and end with a recommendation of the best option.

A comparative analysis weighs the evidence between two or more ideas, situations, or products and makes a claim based on evidence about which one is best. What’s best for one group may not be best for another, so it’s important to define the criteria and audience at the beginning. For example, if Jessamyn’s research points to AVs producing significant cost savings, the decision to go with AVs may be best for the company. However, it may not be the best for the drivers who would be replaced. In order for a comparative analysis to be effective and ethical, the items or issues under comparison must be measured by the same standards.

Causal Analysis

A causal analysis looks at why something happens or could happen. Often this variety of formal report analyzes effects or what might occur if a particular decision is made. In other cases, the causal analysis considers what already took place to help decision-makers understand how to prevent future problems or take advantage of opportunities.

For example, if important machinery breaks down in an industrial business, a causal analysis is often conducted to figure out what happened. The report helps the business determine what to do in the future to protect the machinery and the people who operate it. Such a report might also allow the business to plan for better maintenance or replacement of the machinery.

In Jessamyn’s case, a causal analysis might investigate what is causing the current fleet to break down as a part of measuring reliability and revenue. She might also look at ethical issues of AVs or liability issues with insurance companies and how these issues impact the company’s bottom line. Jessamyn explains the research in the findings section and analyzes the research in the report’s discussion section, which helps the decision-maker know if they want to move forward.

Determining cause requires careful analysis. There may be direct and indirect causes. There may be one cause or multiple contributing factors. The researcher must consider what is relevant and avoid rushing to judgment. Causality must be clearly demonstrated through cause and effect evidence. Beware of confusing correlation (two things connected by circumstances) and actual causation (one thing directly impacts something else).

Feasibility Analysis

A feasibility analysis determines if a strategy, plan, or design is possible. Is the proposed decision a good idea for a business or client? Is it economically justifiable? Will the strategy, plan, or design produce the desired results? A feasibility analysis can be invaluable for a business that is weighing the possible benefit of a risky decision. In the example of the organization considering the best option for providing healthcare for its employees, a feasibility analysis might determine whether the organization can afford to go with the best provider and package.

Jessamyn’s formal report that serves as the example for this chapter is primarily a feasibility analysis. Her job is to determine if AVs are a financial, marketable, and operational solution to the fleet’s problems. To make a solid recommendation, she will have to look closely and honestly at both the strengths and weaknesses of using autonomous vehicles.

The technical communicator must objectively assess the possible benefits or drawbacks of a particular course of action, without allowing their personal opinion to cloud the final conclusions. On a personal level, Jessamyn finds the idea of driverless vehicles unnerving, but she needs to set aside her opinion as she collects and presents her data. A feasibility analysis also considers alternate points of view in the decision-making process. The best feasibility studies will weigh the pros and cons of the collected data before recommending a course of action. Beware the ways bias can sneak in when you interpret data or draw conclusions. Analysis requires a steadfast commitment to objectivity.