Teaching information literacy and writing studies - Grace Veach 2018

Using information literacy tutorials effectively

Pedagogies and Practices

INTRODUCTION

As is common for librarians and composition instructors, the authors of this text, humanities librarian Vandy Dubre and assistant professor of English Emily Standridge, collaborated on various classroom projects. Our partnership was, though, what Rolf Norgaard (2003), a professor of English, calls “a partnership of convenience,” characterized by the stereotypical “quick field trip, the scavenger hunt, the generic stand-alone tutorial, or the dreary research paper” (p. 124). We worked together as needs arose but did little in terms of “genuine intellectual engagement” (p. 124). That changed when tasked with the improvement of information literacy (IL) instruction for the students at a medium-sized regional university, the University of Texas at Tyler (UT Tyler), when the university created an Information Literacy Directive, which, in full, reads:

Faculty members and professional librarians at The University of Texas at Tyler believe that the ability to evaluate and incorporate information strategically will be critical in creating a competitive advantage for students. Graduates will be skilled in locating, evaluating, and effectively using and communicating information in various formats. They will be aware of the economic, legal, and social issues concerning the use of information and will be able to access and use information ethically and legally. Within this comprehensive information literacy effort, the University will strive to develop the ability of its students to use information technology effectively in their work and daily lives. UT Tyler’s information systems will be state-of-the-art and will serve as the central hub influencing, supporting, and integrating academic and administrative processes across the University. (The University of Texas at Tyler, p. 3)

This new directive provided the urgency to implement some of the ideas we had been discussing about improving pedagogical methods for library and composition interactions. The directive called for reaching students across multiple disciplines, and we wanted to do more than just disconnected lessons with little value placed on them. We also wanted to value the limited class time composition instructors had with their students. We were searching for a model that would teach the amount of information literacy dictated by the university, have flexibility for faculty and students in completion, and have the ability to maximize the impact of hands-on librarian instruction.

We knew “one of the major difficulties information literacy practitioners must contend with is how to make information literacy embodied, situated, and social for our diverse student body” (Jacobs, 2008, p. 259). We wanted to offer individualized and comprehensive lessons to all first-year composition students, but we lacked the time or resources to develop such lessons from scratch. The Muntz Library leadership at UT Tyler decided to start the IL program with purchased lessons from Research Ready-Academy (RR-A). RR-A was designed by information literacy librarians and aligned with the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) information literacy standards (ACRL, 2000). The ACRL standards identify criteria for the “information literate” person and break each criterion into “performance indicators” and “outcomes.” The desired learning outcomes and assessments of those outcomes provided confidence that RR-A would have the rigorous content dictated in the IL directive. Additionally, RR-A reported multiple points of data about student performance, painting a nuanced picture of what students were learning as well as where they were having difficulties. RR-A is split into three “levels”; each level begins with a “Pre-Test” to assess what students know going in and ends with a “Post-Test” to assess what students have learned (or not learned) through that level. Each “level” is broken down into multiple “courses” (see Table 10.1), which cover specific areas of IL with quizzes and activities built in to assess learning of the concepts at each stage.

TABLE 10.1 Courses Within the RR-A Levels

Level 2 |

Sources, Sources, Sources |

Website Evaluation |

Conquer the Research Process |

Cite It Before You Write It |

Inquiring Minds Want to Know |

Level 3 |

Source Identification |

Databases & Open Web |

Identifying Source Credibility |

Ethical Research |

Conquering Research |

One of the main concerns in using RR-A was the information being too “canned,” created to meet the ACRL guideline but not actually meeting the needs of our students in our courses. Jacobs (2008) notes similar concerns, stating, “because learning, teaching, researching, writing, and thinking are inherently messy processes, the neatness of ACRL-inspired rubrics does presses a certain allure. It is no wonder, then, that administrators turn to them as a way of managing the messiness of pedagogical reflection and curricular evaluation” (p. 258). Ultimately, RR-A made it clear that we could adapt the materials as needed to meet our needs and objectives while working within their tested and rigorous standards. They were happy for us to change text, examples, and the order of delivery of the lessons to work with our courses. With limited time and resources to develop fully individualized lessons, let alone be able to justify their assessments across situations, this was the best option available.

We also found that RR-A answered a call for a best-practices teaching method for IL. Bean (2011) notes the importance of engaging students at multiple points through multiple methods as a means of increasing critical thinking skills. RR-A does just what Bean calls for: each “lesson,” a subset of a larger “course,” includes several “quiz” questions reviewing the material immediately after it is presented; short answer questions appear at the end of each “lesson,” reviewing the material as a whole. At the end of each “course,” several short answer questions are presented to review material on a larger scale. When added to a course that often already instructed students on IL matters, RR-A further increased the multiple points and methods of instruction in IL. Plus, students and instructors are able to see students’ scores on IL matters at multiple points and through multiple methods within RR-A, giving another window into how students are actually learning the material. This method of instruction was what we wanted to see across all sections, so we were encouraged to see it as part of this product from the beginning. We would only need to modify things slightly, if at all, based on our individual needs.

RR-A was also the ideal product from the perspective of implementation. All of the set answer quiz questions were graded automatically, including the pre- and post-test scores; they required no additional labor to process. The short answer questions did need to be graded individually, but Vandy argued that that job could easily be taken on by the librarians because they are experts in both IL and RR-A. RR-A did more than just collect information. Pre- and post-test scores were compared in the program itself, and a number of statistical analyses on all of the assessment data was provided through the RR-A platform. This allowed unprecedented insight into student work with a minimum of effort. Further, RR-A technology was convenient to integrate into the learning management system, so both on-campus and online university classes could use the materials easily.

We anticipated having to defend the use of RR-A against claims that it would be “disconnected from pedagogical theories and day-to-day practices, but it also begins to lose sight of the large global goals” of IL in higher education, becoming nothing more than an extra set of activities divorced from the content of the class (Jacobs, 2008, p. 258). Our goal was to start with the lessons RR-A had already created and, through our “genuine intellectual collaboration” (Norgard, 2003, p. 124), build something suited exactly to the needs of our institution.

Our Approach

This chapter traces our process from Research Ready-Academy’s existing information literacy lessons to completely customized information literacy education for the University of Texas at Tyler’s first-year composition classes. We offer what Jacobs (2008) calls “actual classroom practices and activities not, as Chris Gallagher has described, so that we may present ’replicable results’ but to ’provide materials for teachers to reflect on and engage’” (p. 260). The information we present does support the idea that information literacy instruction is effective when provided through first-year composition using both a structured curriculum package created independently of any particular course with a reflective writing element that is particular to that FYC course.

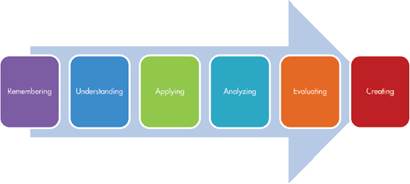

This chapter traces our path to this conclusion by reviewing our pilot semesters using RR-A and the refinements to our approach as we proceeded. We conclude with evidence from student writings, which shows that they have achieved a new kind of thinking about their IL. This new thinking is indicative of their movement in Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy.

DATA

Pilot 1: Lessons in One Semester of FYC

Model

In the spring 2015 semester, we started with one section of English 1302, the second semester of the FYC courses offered at UT Tyler. Our goal was for students to complete both Level 2 and Level 3 of RR-A and to increase their post-test scores. RR-A was used as an IL-focused supplement to the implied IL instruction of the other course materials. RR-A materials were graded mostly on completion as it was assumed that the “active learning” and “application” seen in the other areas of the course were more important to their learning (Porter, 2014).

Rationale

English 1302 was selected because it is a required course, whereas other FYC courses are optional in students’ degree plans. Students from all majors take English 1302 and are not isolated by major, and the course was specifically designed to be interdisciplinary, a common goal among similar programs (Deitering & Jameson, 2008; Palsson & McDade, 2014).

Outcomes

We were encouraged about the possibility of instructing a large majority of students (we will never reach “all students” with implementation in only one course) since we saw such a large number of majors represented in this pilot: Nursing, Biology, Accounting, Spanish, Human Resources, and Education. However, many of the students failed to complete the RR-A materials; while 12 students completed the RR Level 2 pre-test, only 2 completed the post-test. Only 7 of the beginning 12 students did the Level 3 pre-test, and only 2 of those did the Level 3 post-test. This lack of completion was likely due to the language of instruction, which failed to say “take the post-test” directly. Still, students were not completing the materials and we felt that we would need to make some important changes in how the materials were presented in order to meet the directive’s imperative to instruct “all students” with a “full range of instruction.”

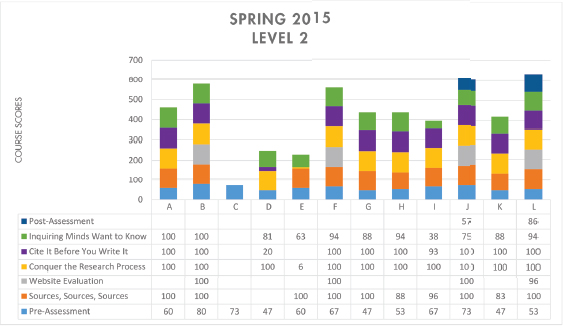

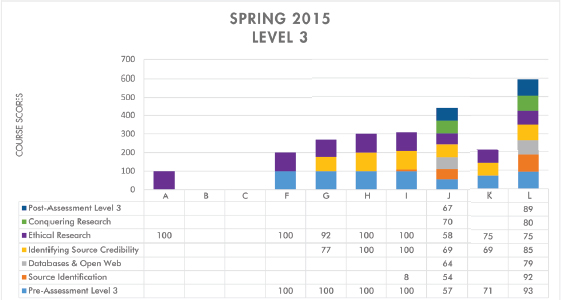

For the students who did complete the pre- and post-tests, Level 2 results showed an increase while Level 3 showed a decrease in scores. This result was perplexing because in-class discussions showed students were capable of fluent discussions of the new IL material in both levels of RR-A. The quiz scores helped illuminate the matter further: students were having trouble retaining what they learned. Students showed increases in the scores from the pre-tests to the quizzes at the end of each course in Level 2, demonstrating an ability to remember the material for the short term (see Figure 10.1). A similar, although less marked, change in scores was also shown in Level 3 (see Figure 10.2). The lack of post-test scores and the decrease in post-test scores seen in Level 3 combine to show a picture of students not remembering the material beyond their moments within RR-A, likely because they were not applying the information beyond the immediate setting. Even though close analysis of student writing was beyond our original scope, specific trends seen in grading revealed that they were not applying what they were doing in the supplements to their “main” writing work.

Figure 10.1 Spring 2015 (Level 2) student scores on all courses. Students who did not attempt the course are left blank.

Figure 10.2 Spring 2015 (Level 3) student scores on all courses. Students who did not attempt the course are left blank.

Changes

Based on students’ requests on satisfaction surveys for “more time to do” the work and more quizzes to process RR-A as well as the low completion rates, we knew that completing Level 2 and Level 3 in one semester was simply too much work. Splitting the levels over the two-semester FYC sequence made sense.

We also decided to change how the RR-A lessons were used. We wanted to make clearer the connection between the RR-A and the class material as students claimed RR-A was not “relevant to the subject matter.” This meant revising both the RR-A materials and the course content. At the end of our first pilot semester, we were convinced of the potential of our project to meet many of the IL Directive goals using RR-A, but we also saw room for a great deal of improvement.

Pilot 2: Expanding to Two Semesters of FYC: English 1301

Model

With the new semester of our pilot study, we wanted to increase students’ retention of the RR-A information by moving the RR-A lesson timing relative to class discussions and by including the language and terminology of RR-A within class discussions more consciously and purposefully. This semester, we worked with English 1301, the first of the FYC courses offered at UT Tyler, and included Level 2 courses as they best matched the course material.

In addition to the reconfiguring of the content delivered, the reporting of quiz evaluations was changed. Vandy agreed to compile scores from multiple choice and short answer questions and forward the information to Emily. Emily would incorporate this data into the class grading scheme. This grading arrangement eased the issues students encountered with their “proof” of completion while also increasing the importance of actually learning the material, as that knowledge would be reflected in their grades.

Our goal in the second pilot was to obtain higher completion rates, to see improvements in post-test scores, and to create improved engagement with the RR-A material among students as measured by in-class discussions.

Rationale

The guiding assumption of Pilot 1 was that highlighting the IL concepts inherent in the work students were doing through RR-A would increase students’ IL abilities, but this was not seen to be accurate. More work was needed to “situate [IL] instruction in the lived academic and social lives” of our students (Norgaard 2004). By directly linking the RR-A lessons into class content, using shared vocabulary among the elements of the class, and grading on answers as well as completion in RR-A, we hypothesized that Pilot 2 would be more beneficial for our students.

Outcomes

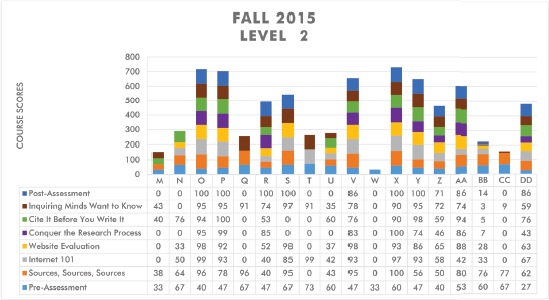

Eleven students completed the pre- and post-tests and 91% of those students showed an increase in their post-test scores. This shows an increase in both completion rates and knowledge measured. We were satisfied that this increase in post-test completion revealed students were being exposed to all of the information we wanted, so we were well on the path to meeting the directive. We still had a disappointing eight students begin but not complete the work; our efforts to increase the importance and relevance of the RR-A courses were only partially effective. Student quiz grades were also consistent with our previous pilot: they showed an increase from pretest to quiz, so students were remembering the information during the course of RR-A (see Figure 10.3).

Figure 10.3 Fall 2015 (Level 2) student scores on all lessons.

A new trend emerged as we kept closer track of students’ performance on the short answer questions versus the multiple choice answer questions. Students would score well on the multiple choice questions but failed to do well on the short answer—type questions. This pattern of scores indicated that even though students were viewing the information and able to remember it, they were not able to apply the information. Students were simply remembering the material from RR-A, and probably only for a short time; if we wanted to increase their ability to retain and apply the ideas, we would need to make further adjustments. In-class discussions showed students were more invested in this work than in Pilot 1, but they were not applying their learning as much as we wanted.

Changes

Something needed to be added to increase students’ engagement with the material to move them past the remembering stage of learning. Students needed to do more writing in conjunction with the RR-A lessons to get this increased critical thinking (Bean, 2011). We decided to add reflective writings built on those already a regular part of the course, but with specific consideration of RR-A and IL; as Yancey (1998) states, reflection allows students the “articulating of what learning has taken place, as embodied in various texts as well as in the processes used by the writer” (p. 6). Reflective writings along with the other data points would provide a nuanced picture of students’ IL skills while also helping them do more than just remember the lessons temporarily.

Pilot 3: Lessons in Two Semesters of FYC With Reflective Writing

Model

Pilot 3 occurred in spring 2016 with English 1302 and Level 3 of RR-A. The incorporation and pacing of the RR-A lessons was the same as in Pilot 2, but we built upon established reflective writing assignments by including questions about how the information presented in the RR-A lessons impacted writing throughout the semester and by creating a distinct writing assignment directly related to the RR-A lessons. Students completed reflection questions at the end of each writing project. The prompts asked them to consider how the RR-A information added to their work in the project. At the end of the semester and as scaffolding for their final exam paper, students were asked to “speak about the benefits and shortcomings of the Research Ready activities” using “specific elements in the Modules (lessons)” to “find at least one beneficial thing and one negative thing” in a separate paper. They were given a set of questions to consider in their writing:

What are the main things Research Ready was attempting to teach you?

How was Research Ready attempting to teach? (Using what methods?)

How much of Research Ready did you already know? How much was new?

Do you think you learned using Research Ready—why or why not?

What do you know about yourself as a learner because of Research Ready?

Students worked on drafts of this paper with teacher and peer feedback. Their writing received a final grade; students were familiar with this pattern of work as it was followed throughout the semester. The goal of this assignment was to help students learn the ways they were expected to perform “reflection” on the final exam paper: using specific examples from the lessons and thoughtfully answering the questions given, in addition to helping them retain and apply their IL learning from RR-A. The questions were designed to help students postulate about the impact of RR-A information on their coursework as well as their future lives, which, as Norgaard (2004) suggested improves learning and retention of material.

Rationale

While we knew the importance of writing in learning, we did not want to add what seemed like another required writing feature to English 1301 and 1302, especially since so many of the assignments already in place achieved what we wanted from information literate students. We also did not want to encounter the issues Palsson and McDade (2014) encountered in setting up a common assignment; namely, we wanted to keep instruction firmly situated in the hands of each instructor. Reflection, though, adds a common feature with common evaluative methods, which works for any classroom or goal (Yancey, 1998). We thus thought that it was time to add a reflective writing feature.

Outcomes

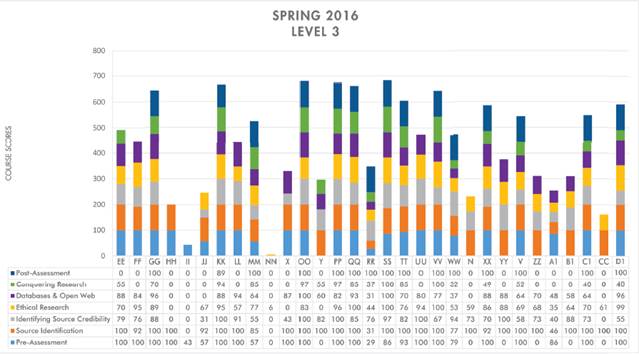

Seventeen out of the initial 30 students completed the pre- and post-tests in RR-A during the spring 2016 semester. Their scores were consistent with those in previous semesters, as shown in Figure 10.4.

Figure 10.4 Spring 2016 (Level 3) student scores on all lessons.

Unlike previous results, just 82% of students showed an increase in their scores from pre-test to post-test. While this was initially concerning, as it seemed to indicate that students were learning less in the RR-A courses with the addition of written reflections, there are some potential explanations for the lowered score. First, since more students actually completed both the pre- and post-tests, there could have been some selection bias in the previous semesters. Students who knew much of the material to begin with may have been the ones to complete the tests rather than all students, making Pilot 3’s percentage simply a better representation of this population’s growth since more completed both tests. Second, since students were interacting with the material in more depth, they could have been less certain of what they knew. As students grapple with complexity, we know that they sometimes “drop” what they have previously mastered. Potentially the same is true here. Third, because this was such a small sample, the results from this class may just have been a fluke. Overall, there was a 35% increase in the scores between pre- and post-tests, which means the class as a whole was learning, whatever else was happening. While this drop was puzzling, the further data from the reflective writings eased some of our concerns.

Gleaning information from the reflections was more complicated than grading quiz questions. We did a two-round coding process on the reflective essays: first, reading the essays individually, creating coding categories based on the patterns noticed. We then compared categories and refined them to “suggestions,” “how I learn,” “already knew/expanded knowledge/wrong information,” “writing skills,” and “topics” discussed. With the new set of coding categories, we recoded the essays together.

The “suggestions” and “how I learn” pieces of the reflections were responses to either the prompt or in-class discussion; they had little to do with meeting the IL Directive, but they were ultimately important in the ways discussed below. The code about what students knew or did not know was very revealing for the directive. One student wrote, quite impactfully, “Of course I knew what primary and secondary sources were, and basic information like that. What surprised me, however, was the amount of information I didn’t know” (Student 14.004). Throughout the pilots students noted how they felt that RR-A was not new material, but, like this student, soon realized that there was far more depth to the topics than they had previously been introduced to. Eighty-nine percent of students thought the material in RR-A was familiar to them to some extent, claiming that they “already knew most of what was presented.” Upon further analysis of the essays, though, we found that 79% of the students were able to name at least one area where they expanded their knowledge on a previously known topic or learned a new facet of those known topics. So students were “reviewing” their knowledge, but they were also expanding, refining, and gaining new knowledge in the process. The reflections revealed that students were deepening their understanding of the topics, which was important since it called for students to have a working knowledge of IL skills.

The “writing skills” elements showed students applying what RR-A was teaching to their work, with 25% discussing finding sources more effectively and efficiently than they previously had or other writing skills. For instance, one student said, “my writing is also improved after doing the research ready assignment because it informed me about researching a topic on the internet without wasting a lot of time such as using proper search engines for scholarly articles instead of spending an ample of time on the open web and finding the vague information” (Student 3.006). In addition to technology-specific writing skills, students wrote about how RR-A improved their writing skills more generally, such as, “this helped me in future writing as I am able to take essays and learning in small chunks rather than try to complete everything in one sitting” (Student 3.004). Students were thus using the information they learned as well as applying it to effective communication in multiple situations, an element of the directive not seen in any of the other pilots. Finally, the topics mentioned most often were about sources (79%) and plagiarism (54%), indicating that students were remembering, outside of RR-A quiz questions, information about finding and ethically using sources, another of the IL Directive elements not seen as clearly in previous pilots. Overall, students in Pilot 3 showed a much greater growth in their information literacy than in any other semester.

There was a small but important 11% of the students who claimed to know specific information from RR-A, but in the essay wrote information that was incorrect or not in the RR-A platform at all. For instance, a student wrote, “I learned that primary sources are usually peer-reviewed journals and secondary sources, like magazines usually have advertisements” (Student 4.004). This incorrect understanding of primary and secondary sources suggests a student who was just “clicking through to get completion” as it correctly identifies a topic of discussion in the tutorial. Some students are not going to engage with the material, no matter what. At least this student was considering types of sources in a way that would not harm him or her in the future. Another student wrote about improving grammar knowledge during RR-A, which was part of the course materials, not the RR-A. This student’s response, despite not meeting the assignment, argues for the work we have been doing, as it shows that the student did not really distinguish RR-A from any other course material.

Overall, students were starting to connect the information from Research Ready and the course to create a cohesive idea of what information literacy means in practice and to think about how they will be able to apply those skills throughout their lives when they had both the RR-A lessons and the reflective essay incorporated in their course.

Benefits of This Approach

We had two main goals in our process: we wanted and needed to find a method for meeting the IL Directive set by our university, and we wanted to see students develop their critical thinking in multiple directions in order to impact their college careers and life after college. We were frustrated by our students’ inability to apply learning from one course to another or one situation to another, especially as they used online resources. Through these pilots, we found that using a premade (but adapted to our situation) IL curricula along with reflective writing met our goals. The benefits of this model are seen through the lens of the IL Directive, Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy, and students’ reflective writing.

IL Directive

The IL Directive had three main components, in which students showed marked improvement during our third pilot:

1.Students are skilled in locating, evaluating and effectively using and communicating information.

2.Students are aware of economic, legal, and social issues concerning the use of information.

3.Students are able to use information technology effectively in their work and daily lives.

As discussed throughout, students were making progress toward meeting the elements of this directive from Pilot 1. In each iteration, we saw students interacting with the material, especially in locating information and being aware of the issues concerning the use of information. In Pilot 3, we saw students engaging in all areas of the directive. Students saw the information, were tested on it, and wrote about it. The student writing artifacts suggest they were both being instructed on and applying the information in their English classes, and students claimed to be able to use the information in other classes as well. Students developed the information literacy skills to have the “competitive edge” the directive asked for; with reflection, though, students were also developing their critical thinking skills in many areas, demonstrating growth along Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy (see Figure 10.5).

Figure 10.5 Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy. (Data from Krathwohl, 2002.)

Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy

The quizzes, both multiple choice and short answer, included in RR-A primarily measured students’ remembering skills—the lowest level. The set answer questions were drawn directly from the lessons, with wording nearly the same as in the lessons. The short answer questions, which drew more on contexts in which the information would be used, were aimed at the understanding element of Bloom’s. The fact that students in Pilots 1 and 2 did not do as well on the short answer questions shows that they were not advancing in this area. When we moved to Pilot 3, students showed an increase in their short answer scores, demonstrating their growth from remembering to understanding. With the reflective writing, many students showed even more growth, up to the analyzing and evaluating stages.

Students were asked to “analyze” source information during RR-A; this analysis was seen in multiple courses including “Sources, Sources, Sources” and “Identifying Source Credibility.” The short answer quiz responses demonstrated some limited analysis, but students showed detailed analysis in their reflective writing on two levels:

1. Analysis of sources within their own writing. For instance, “Being taught how to use a database and what good sources looked like, I was able to differentiate the good from the bad to improve my papers” (Student 1.004). Additionally, another student discussed how RR-A helped him or her learn to “identify if [sources] are credible or not and also if they are considered primary or secondary sources that really helped me use those article in this class and other more effectively” (Student 11.004). Both of these examples reveal students’ own awareness of how and when they “analyze” source material. Students then reported using that analysis to their benefit when writing papers. While we cannot be certain this portrayal of “analysis” is entirely accurate, the fact they write about it indicates this level of thinking is present.

2. Analysis in action is seen as they answered the question “What do you know about yourself as a learner because of Research Ready?” Students variously described themselves as “visual learner,” “impatient learner,” and “to the point learner” and discussed how “reflecting over what I gained from Research Ready encouraged me to not only understand what I learned, but to also recognize how I learned it” (Student 4.006). Many students really dug into how they retained information and how they write. For instance, Student 3.004 noted that RR-A “helped [sic] me in future writing as I am able to take essays and learning in small chunks rather than try to complete everything in one sitting.” This student was able to recognize the pattern of instruction in RR-A as a pattern of writing that would help him or her be more successful. A student who claimed “although I personally prefer learning in a classroom with a professor” because he or she enjoyed personalized attention, argued that “doing Research Ready really helped me as a student by teaching and explaining the lessons in a different way” (Student 2.004). This student was able to see beyond personal preferences in order to analyze the learning elements and recognize the strength of them. Students enact “analysis” in their writing as well as discussing it as a process they have completed. With both of those elements present in the reflective writing, it is safe to say that students have indeed expanded their thinking in this way.

“Evaluating” was seen as students spoke about the value of the RR-A experience. In Pilot 1, students claimed that the lessons were “boring” or “super cheesy.” While these are critiques of the program that have some validity, they lack specificity and do not really evaluate the program as such. By Pilot 3, though, we were seeing students pointing to specific benefits and detraction leading to an overall evaluation of the entire learning experience. For instance, one student said, “because of the narrative, Research Ready made it personable, even if it was just cartoons with talking bubbles” (Student 6.006). This student, instead of calling the art “cheesy,” discussed why that simple addition made his or her learning of the subject more effective. Similarly, another student lauded the use of clever examples and well-structured explanations to help him or her “personally understand what research ready was trying to explain” (6.004). The ability to tie the learning to specific examples and explanations and thus claim its overall usefulness is an excellent evaluation. Even the students who did not find the course useful showed elements of evaluation in their work. Student 13.006 stated, “I am not saying that this research academy work was a waste of time” even though it started to “feel like busy work” because the lessons were “drawing things out and doing cartoons for students who are in college.” Even while noting that the style of instruction did not suit his or her learning preferences, this student thought that it encouraged a “focus on each subject” and that the lessons “do something different so that these topics that we have to do” feel less repetitive and stick to “just the facts.” This evaluation points to a problem the student identified and looks to a solution for that problem, which fits into Bloom’s “analysis” and “evaluation” levels.

Student Learning Preferences

As was mentioned above, student learning was a theme seen among many of the reflective essays. In addition to demonstrating students’ ways of thinking according to Bloom’s Taxonomy, discussions of their learning allowed us insight into how to revise the lessons for future use. Many students (14%) noted how the small chunks of information were useful for them. They noted that “this is a good way to teach as it is not overwhelming at any point” (3.004). Since students in Pilot 1 complained of not having enough time or interaction with the material, this statement was gratifying; splitting the levels over two semesters was a good choice. Also, students who feel overwhelmed will not learn as effectively, so students noting their comfort with the way information is presented indicates they are in a mindset to learn (Gute & Gute 2008). Students also noted that delivery of RR-A was helpful, with one stating it “allowed me to be more flexible with my learning styles and have some control of my environment” (Student 1.006). Control is another marker of student engagement with the material. We saw through the reflections that Pilot 3’s model set students up to learn as much as possible.

Reflections also revealed that students need examples and applications in order to learn most effectively. Student 5.004 said, “I now definitely know that I will retain information better when I write the information given and actually put it to use” (Student 5.004). While this information does not come as a surprise to educators, allowing students to come to this conclusion through experience cements that learning principle for them. Whether that “writing things down” is done through independent written reflection or quizzes used in RR-A seems less important; 43% of students claimed frequent quizzes and other assessments aided in their work, indicating this practice helps them pay attention to the lesson and apply what they learn immediately. Keeping the application questions is important for RR-A’s success, even if students voice complaints.

Students also valued the multiple modes of instruction as much as we theorized they would. Students need instruction to come in multiple verbal patterns, as evidenced by 36% of reflections noting the importance of definitions in conjunction with examples in their understanding of important topics. Working beyond just verbal patterns is crucial as well. Student 6.006 noted, “sometimes it can be difficult to understand what an educator or education program is trying to teach, but because of the narratives research ready made it personable even if it was just cartoons with talking bubbles.” Adding a visual story, even a simplistic cartoon, can really change the impact of a lesson, helping students learn more effectively. This is supported by the fact that 21% of reflection noted the importance of added visuals in students’ engagement with and processing of the material.

MOVING FORWARD

Problems With Large-Scale Implementation

In fall 2016, we offered a “soft start” to the program. Instructors were given the choice of incorporating the Pilot 3 model into their courses. Few chose to do so; many who did accept the invitation used methods that clearly misunderstood the goals of the project, sticking to inserting the “canned product” into their course with no consideration of how it fit into their teaching or grading schemes at a larger scale. For instance, one instructor did not want to change the planned class syllabus so added RR-A courses and reflections as “extra credit,” thinking it would accomplish the same goals as the pilot with the incorporated reflection. These flawed adoptions were in spite of sharing the data from the pilots and a sample syllabus showing how and where the lessons could be placed.

We attempted full implementation to all sections of FYC courses in spring 2017. All English 1302 instructors on our campus were asked to use the model of courses and reflections used in Pilot 3. We saw 12 sections adopt the program, which was not full implementation, but did give us a bigger picture of the ways to work with faculty and the issues with student use of the lessons. Faculty struggled with technical concerns as well as ideological issues related to the importance of the work to their course. As in our “soft start,” they assumed the “canned product” could not work for their individualized needs. We also heard repeatedly that the lessons were covering material that was already implied in the course and that it was “busy work” for students. This was all despite a workshop discussing the needs for the lessons as well as why they were best practices for diversifying instruction.

Additionally, the 12 sections created a great deal more work for Vandy than anticipated. She found herself managing all the technical problems and complaints without the support that she needed. Out of these issues, we created a focus group of five instructors teaching both FYC courses. The goal of the focus group was to increase faculty “buy-in” for the program while increasing understanding of the purpose of the lessons in meeting the directive while meeting faculty concerns. The discussion resulted in planned adaptations of the program in terms of faculty control and personalization. The Focus Group worked together to both improve the lessons and also align the lessons themselves with the topics presented in the sections (see Table 10.2). Looking at the types of concepts taught in English 1301 and English 1302, some lessons were moved between the two sections and some lessons were found to be redundant. The new collection better suits the faculty and the needs of each section. We removed short answer questions from the lessons since faculty felt grading of those by someone outside their class removed the importance and value of the work. Instead, starting in fall 2017, all faculty were given options for short answer questions to incorporate into their established quizzes and reflection during the course. This adaptation also relieved some of the extra work on Vandy and eased the complaints of students about the grading of the work. It also increased faculty’s engagement with the lessons and the purpose of the program. We also decided to further revise all of the lessons using avatars resembling the diverse population at UT Tyler. While this was not directly requested by the focus group, we realized that making the lessons appear more personalized with these recognizable “faces” rather than the generic drawings originally used would increase the impression of the personalization that was already occurring but that seemed invisible to the faculty. We also thought that this change would help students engage with the material more as the lessons were “coming from the mouths” of faces they “knew.” Avatars were created with the diversity of our student population as well as specific types of “majors” that reflect the different types of research needs, such as the differences in nursing, humanities, and engineering research. Using these examples helps the students understand how these concepts relate to them in their fields of study and careers. All of the skills were discussed in both academic and personal life settings, emphasizing how each skill could be used in the school/work environment and in everyday life. Ultimately, the focus group helped us think about ways of discussing and displaying our lessons that moved beyond the impression (however false it might have been) that these were “canned lessons” that could be added to a class with no engagement from the faculty.

TABLE 10.2 New Course Schedule Within the RR-A Levels

Level 2 |

Internet Basics |

Website Evaluation |

Scholarly Thinking & Writing |

Plagiarism Citations |

|

Level 3 |

Source Identification |

Source Credibility |

Using Databases |

Ethical Research |

Research Processes |

Changing With the Times: When Your Product Disappears

After all of our efforts to learn the best way to work with Research Ready-Academy, we learned the company had been purchased and would no longer be available. Sadly, this is not an uncommon occurrence, especially when looking at digital tools. Because of our history with the company, though, we were able to use all of their course content with appropriate recognition, so we do not have to develop new lessons. If this kind of usage were not an option, we could have created our own lessons; however this would have forced a drastic time issue and would have delayed full implementation for possibly another year.

As we scrambled to adapt the material to a new platform (Softchalk, for us), we were able to adjust the materials along the way, taking into consideration the feedback students had given us. We are building in more content with a direct link to course materials. We are also incorporating the kinds of assignments used in English 1301 and 1302 into the courses. We are using the RR-A platform to springboard our program, adapting it completely to our campus’s needs.

Importance of Reflection

The most important thing we learned in this process was the importance of the right kind of reflection. Simply using the product as marketed, even with short answer questions that required students to apply the material taught, did not result in the learning gains we hoped to see. When we added the reflective questions to the process of their papers and the independent reflective essay, we saw completion increase and engagement with the material increase. Students were able to make larger scale connections to the tutorial, their classwork for English 1301/1302, courses beyond English, and themselves as students and future professionals.

While the importance of reflection was indicated through all of our research, it was not until we saw the methods of reflection actually working through the students’ own words that we were convinced of the ultimate success of this approach. With the evidence from these reflective pieces, we are able to fight the concern often raised about the use of a “canned product” for individualized learning.

CONCLUSION

Vandy and Emily started working together because Vandy could offer library lessons to Emily’s classes, as was the standard procedure when Emily joined UT Tyler. We found, though, that we work well together and our ideas build on each other to improve the offerings we can give to students. When the Information Literacy Directive came down from the university, we realized we could use the directive to our advantage to make larger scale changes to IL instruction campus-wide. We felt as if we had a strong grasp on what was needed when we started, but our pilots allowed us to use our individual strengths together to create a data and theory—driven method of IL instruction and critical thinking skills that impacts students across disciplines and throughout their careers. We have devised a way to use a standard product as a starting point for truly individualized instruction without a huge budget or lengthy timeline. We continue to work together to address the needs of the students and the faculty. Even if the approach we have used here is ultimately discarded, which we believe and have evidence suggesting it should not be, we know this collaboration between the library and FYC faculty will continue to be fruitful because it is a true meeting of minds.

We share our results for several purposes. First of all, we have further evidence of the benefits of students’ reflective writing in learning. More importantly, we have been able to show how our collaboration in refining our IL lessons and pedagogy have worked so others can see how such a development can occur. We took Jacobs’s (2008) call to show such work to heart. Finally, we want to argue for the continued work of collaboration between libraries and composition.

REFERENCES

Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL). (2000). Information literacy competency standards for higher education. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/informationliteracycompetency

Bean, J. C. (2011). Engaging ideas: The professor’s guide to integrating writing, critical thinking and active learning in the classroom (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Deitering, A-M., & Jameson, S. (2008). Step by step through the scholarly conversation: A collaborative library/writing faculty project to embed information literacy and promote critical thinking in first year composition at Oregon State University. College and Undergraduate Libraries, 15(1—2), 57—79.

Gute, D., & Gute, G. (2008). Flow writing in the liberal arts core and across the disciplines: A vehicle for confronting and transforming academic disengagement. Journal of General Education, 57(4), 191—222.

Jacobs, H. (2008). Information literacy and reflective pedagogical practice. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 34(3), 256—262.

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4): 212—218.

Norgaard, R. (2003). Writing information literacy: Contributions to a concept. Reference and User Services Quarterly, 43(2), 124—130.

Norgaard, R. (2004). Writing information literacy in the classroom: Pedagogical enactments and implications. Reference and User Services Quarterly, 43(3), 220—226.

Palsson, F., & McDade, C. L. (2014). Factors affecting the successful implementation of a common assignment for first-year composition information literacy. College and Undergraduate Libraries, 21(2), 193—209.

Porter, B. (2014). Designing a library information literacy program using threshold concepts, student learning theory, and millennial research in the development of information literacy sessions. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 19, 233—244.

Robert R. Muntz Library. (n.d.). Mission and policies. Retrieved from http://www.uttyler.edu/library/about/mission-policies.php.

The University of Texas at Tyler. (n.d.). Inspiring excellence strategic plan 2009—2015. Retrieved from https://www.uttyler.edu/president/docs/Strategic_Plan.pdf

Yancey, K. B. (1998). Reflection in the writing classroom. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.