Teaching information literacy and writing studies - Grace Veach 2018

Using object-based learning to analyze primary sources

Pedagogies and Practices

The role primary sources play in research can be largely unknown to undergraduates. Though they are often required to use them, many students are unfamiliar with what they are, where they can be found, and how they can be used. With a large amount of research detailing information anxiety among undergraduates, the added complication of finding and using primary sources can set first-year students up for failure. Designing an information literacy workshop focused on primary sources can not only teach first-year students how they fit into the larger research conversation, it can increase engagement with research materials and enhance research skills to create more capable writers and researchers.

UNDERGRADUATES AND PRIMARY SOURCES

First-year writing programs are designed to be an introduction to academic research and writing. Traditionally, the introduction to research would chiefly include how to use secondary and tertiary resources, but there is growing recognition among instructors and librarians alike of the need to provide a more well-rounded view of and experience with information. For the case study outlined in this chapter, which was implemented at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), this began with a foundational understanding of the information environment within which students find themselves. Reflecting its prominence within the education literature, the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education created by the Association for College and Research Libraries (ACRL) incorporates the concept of metaliteracy. Some library literature even heralds reframing more traditional information literacy as a metaliteracy (Mackey & Jacobson, 2011). In the ACRL Framework (2016), students are considered both consumers and creators of information. Mackey and Jacobson (2011) put this into context by highlighting that with the prevalence of participatory environments found on social media and in online communities, a metaliteracy frame ensures that information literacy is taught in a way that reflects the current Web 2.0 environment within which students interact. It relies on the belief that students should understand the intricacies of the relationship between the creation and consumption of information. If they do, they also understand that they are able to add their own analyses of materials to create new information and research. They then have the skills and knowledge to become contributors to the scholarly community and feel confident in doing so. Furthermore, when academic writing and research become more personal, students feel ownership over and interest in what they are being asked to do (Mackey & Jacobson, 2011). In a major study of the relationship between primary source use and undergraduate education, the Students and Faculty in the Archives (SAFA) project found that after students were able to engage with primary sources, they showed greater academic engagement represented by their level of interest and satisfaction (Anderson, Golia, Katz, & Tally, n.d.). Students also demonstrated better academic outcomes than their peers, represented by higher course grades and higher rates of course completion (Anderson et al., n.d.). Taking into account the current information environment students find themselves in, a focus on using primary sources has many benefits.

In addition to the benefits of increased engagement and better academic outcomes, the instruction of primary source use enhances critical thinking skills. A 2014 survey from the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) reported that “95% of the chief academic officers from 433 institutions rated critical thinking as one of the most important intellectual skills for their students,” and this was echoed among 81% of employers surveyed in 2011, who desired a stronger emphasis on critical thinking in colleges (Liu, Frankel, & Roohr, 2014, p. 1). The emphasis on the need for teaching critical thinking skills is there, but improving these skills has been a notoriously difficult outcome for instructors to meet. The analysis of primary sources is one way to fulfill that need. In some exercises, such as the one outlined later in this chapter, analyzing primary sources involves viewing a source, asking questions, and postulating what it could mean in a particular context. Such exercises require students to think critically about the materials and to use their own previous knowledge to make inquiries. Krause (2010) found this to be true in her study, testing student knowledge before and after a session involving primary source use. Using Yakel and Torres’s (2003) archival intelligence mode, she created four objectives to measure knowledge of source analysis, one of which was critical thinking. Her results showed that those students who received archival instruction demonstrated an increase in critical thinking, asking questions regarding source validity, limitations, and strengths.

OBJECT-BASED LEARNING IN FIRST-YEAR WRITING

The workshop outlined in this chapter was grounded in an object-based learning approach, and this learning model aims to help students develop the skills needed to draw “conclusions based on an examination of evidence, together with an understanding of the limitations and reliability of evidence” (UCL, n.d., para. 6). It is well suited to facilitate the acquisition of the benefits enumerated previously. Implementing this model allows students to explore the sources for themselves and realize that their personal observations of a source translate and contribute to the scholarly conversation within which the source is included. While this kind of exploration can occur with any object, during the UC San Diego workshops, students interact with topic-relevant primary sources from the campus library’s special collections, as well as digitized materials from other online collections, as needed. The exploration is paired with a worksheet that prompts students to make inferences about a chosen primary source, and think about how it relates to their prior knowledge and what questions it raises for them. The hands-on inquiry of these primary sources from the library collection, where possible, also facilitates teaching students how to find them in the library’s collection and, subsequently, how to use them in academic research and writing.

STRUCTURING INFORMATION LITERACY WORKSHOPS IN FIRST-YEAR WRITING PROGRAMS

There are many elements to consider when embedding a primary source information literacy workshop into a course. In thinking about its structure, a single class may form a partnership with the library, or a programmatic partnership can be formed between a library’s instruction program and a first-year writing program. Further, librarian roles in the workshops might differ based on a number of factors—in some cases, librarians may teach the workshops themselves; in other cases, librarians might be involved in instructional design for the workshops and help in train-the-trainer sessions so that faculty or teaching assistants (TAs) can teach the workshops. Depending on the university and library, the structure of the workshops might differ.

While there are always logistical concerns in instructional partnerships between the library and first-year writing courses, these concerns become magnified when the partnership is not between an individual course instructor and a single librarian, but between a library instruction program and a large-scale, multicourse writing program, such as it was in this case study. With more students, faculty, TAs, staff, and librarians involved, there were a greater number of obstacles that had to be navigated. The UC San Diego Library partnered with the Culture, Art, and Technology (CAT) writing program on campus, which included over 30 stakeholders and 1,000 students. With this number of students, a major consideration was how to facilitate these workshops. Bahde (2011) notes that small class sizes are best for special collections instruction as they make it easier for students to “gather around and share” what they are discovering (p. 77). This is one reason that discussion sections were used in the case study, as a way to achieve the smaller class sizes.

In addition to the concerns discussed above, this case study required the consideration of several other potential issues, including:

✵Communication between stakeholders

✵Creating unified information literacy workshop learning outcomes

✵Primary source selection

✵Training of workshop instructors

Many of these concepts may need to be addressed for a single workshop, and thus many of the following recommendations would be applicable to all primary source information literacy workshops for first-year writing courses, but in this context, due consideration will be given to the added planning and attention needed to implement such workshops in a large-scale program, as was the case for the UCSD workshops.

COMMUNICATION BETWEEN STAKEHOLDERS

In any collaborative effort, effective communication is key to success. The more stakeholders involved in a project, the more crucial communication becomes. Pivotal stakeholders are typically the writing program coordinator or course instructor and the librarian planning the workshop(s). Each of these stakeholders must then communicate with faculty, TAs, and students, or librarians, archivists, and library staff, respectively, to coordinate and confirm the logistics of scheduling the series of workshops so that everyone is aware of what will happen, when, and where.

Communication Between Library Stakeholders

The use of primary sources in information literacy workshops provides a rare opportunity for collaboration between instruction and special collections librarians, but it also presents several challenges. Special collections librarians or archivists often have expertise in teaching the analysis of primary sources in a variety of formats. However, they may not have experience designing instruction for or teaching in large-scale programs like a campus first-year writing program. In this instance, combining knowledge and skills of both types of librarians makes for a better workshop experience for writing students.

Communication Between the Library and First-Year Writing Program Stakeholders

If a single instructor is partnering with the library to create an information literacy workshop, he or she needs to work with students and TAs to make certain they understand the purpose and expected outcomes of the workshop. It is essential that students can relate the content of the workshop to the content of the course; indeed, if there is no course assignment that relates to the information literacy workshop, it can feel like “busy work for both students and the librarian” (Matthew & Schroeder, 2006, p. 63).

If a writing program is coordinating workshops for all first-year writing students, it is important to have buy-in from course instructors, otherwise there may be a sense that the workshops are “an imposition that infringed on their control of the course” (Dhawan & Chen, 2014, p. 419). Furthermore, if the workshops will take place outside of the usual classroom (i.e., in a library classroom), the complex logistics of scheduling means that faculty, TAs, and students need to be aware well in advance when and where the workshops will take place.

CREATING UNIFIED WORKSHOP LEARNING OUTCOMES

Writing programs may have a cohesive set of course learning objectives, but how each instructor approaches those objectives may differ. Further, disparate emphases in courses might be a specific feature offered by the program, allowing students to select the topic they prefer. The writing program courses included in this case study covered such topics as music, storytelling, history, religion, and science. This meant that the information literacy workshop content needed to be flexible enough to accommodate the varied sources necessary for diverse topics, while still fulfilling a common set of workshop learning outcomes.

Information literacy learning objectives can take several forms. They can align with course learning objectives, planned workshop activities, recognized information literacy standards (e.g., AAC&U Information Literacy Rubric; ACRL Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education), or some combination of these options. A sample of the workshop learning outcomes for the case study is included in Table 11.1, which aligns the outcomes with specific workshop activities and threshold concepts from the ACRL Framework (2016).

TABLE 11.1 Learning Outcomes From the UCSD Primary Source Information Literacy Workshop

|

Workshop Outcomes |

Workshop Activities |

ACRL Framework |

Given a definition of types of sources and a list of sources, students will be able to determine if each one is a primary, secondary, or tertiary source |

Think-pair-share exercise where students identify source type (primary, secondary, tertiary) for six provided sources |

Authority Is Constructed and Contextual Information Creation as a Process |

Given a primary source to study (e.g., photograph, song, postcard), students will be able to analyze the source, including describing the item in detail, identifying potential bias presented in the source, generating questions about the source, and evaluating how the source might be used in a college-level paper or project |

Group activity where students are assignment a primary source and given a worksheet with questions to prompt analysis |

Authority Is Constructed and Contextual Information Creation as a Process Information Has Value |

PRIMARY SOURCE SELECTION

When considering a primary source—focused information literacy workshop, selecting appropriate sources for students to interact with and analyze is a crucial step in the planning process. The source or sources used in the workshop should reflect the focus of the class, and instructors should consider using sources in formats other than paper (e.g., sound recordings for a music-themed writing course). A close partnership between writing course instructors and campus librarians during the workshop planning process can assist enormously with source selection, as librarians have intimate knowledge of digital, print, and archival collections, all of which could provide relevant primary sources for any number of topics.

Preservation of Sources

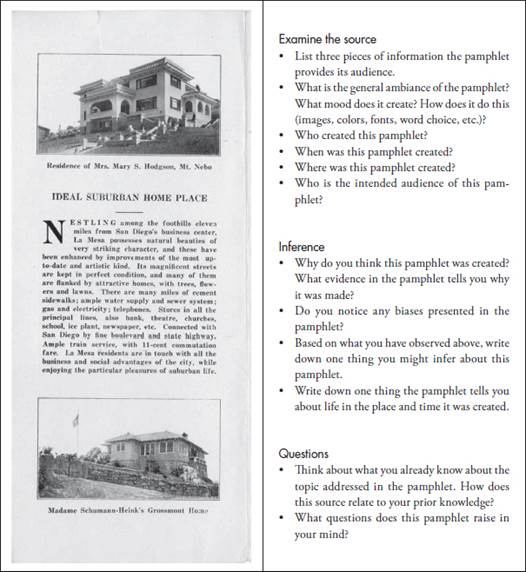

When choosing between digital or physical sources for a primary source workshop, consideration needs to be given to security and preservation concerns for special collections materials, due to the large number of students who might be handling the items. For a single workshop in a small- or medium-sized class, librarians can often ensure the security of the sources, but for large lectures with more than 50 students or multiple classes using the same object, instructors might opt for a digitized surrogate of the item, a born-digital primary source, or a print reproduction of a fragile or rare physical source (Bahde, 2011). In the case study, stakeholders opted for digitized surrogates of more fragile archival items. An excerpt of one source used is included in Figure 11.1, along with the questions provided in its accompanying worksheet to help students begin analyzing the assigned source.

Figure 11.1 Scanned excerpt of a 1915 pamphlet brochure for La Mesa, California, along with sample questions from the UCSD workshops used to analyze the source. (From La Mesa Chamber of Commerce, 1915.)

Format Variety

In this case study, a variety of primary source formats were used, including audio recordings, digital surrogates of pamphlets, differing biblical translations, paintings, and engraved illustrations. Students, instructors, and librarians alike may find analyzing—or teaching the analysis of—sources in nontext formats a disconcerting endeavor. Proper training, discussed in the next section, can help mitigate this discomfort for instructors and librarians, and there are a number of tools available to assist in designing effective information literacy instruction for nontext sources. The first priority should be selecting the most appropriate primary source(s) for the course content, which may or may not mean using nontext items. As mentioned above, preservation and security issues might impact source format as well. However, using nontext sources can offer many benefits to students. Objects such as sound recordings, film, maps, visual art, and photographs can offer profound insight into the ways people thought and acted throughout history. Using a variety of source formats can assist with increasing student engagement in the classroom and, as with text-based primary sources, help give “students a powerful sense of history and the complexity of the past. Helping students analyze primary sources can also guide them toward higher-order thinking and better critical thinking and analysis skills” (Library of Congress, n.d., para. 2).

TRAINING WORKSHOP INSTRUCTORS

Teaching analysis of primary sources is often the purview of special collections librarians or archivists. If these experts are teaching the information literacy workshop(s) for a writing course, there may be no need for further training of instructors. However, if workshops are taught by librarians with other specialties, like instruction, reference, or subject expertise—as was the case at UCSD—then primary source analysis might not fall under their normal teaching duties. Likewise, if these workshops are taught by TAs or course instructors, information literacy instruction in general could be well outside their current skill set.

For workshop instructors unfamiliar with teaching primary source analysis, train-the-trainer sessions taught by special collections librarians would be highly advisable. These experts can walk the instructors through the workshop activities, and perhaps run a workshop simulation, with the instructors posing as students. Additionally, instructors new to teaching this type of workshop might consider investigating sources that provide tips and materials on teaching primary resources:

✵Library of Congress, Teacher Resources: http://www.loc.gov/teachers

✵National Archives, Teaching with Documents: https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons

✵Using Primary Sources: Hands-On Instructional Exercises (Bahde, Smedberg, & Taormina, 2014): http://www.abc-clio.com/ABC-CLIOCorporate/product.aspx?pc=A4130P

ASSESSMENT

With any type of instruction, especially when using a new format, it is important to build assessment into the framework. Due to the one-shot nature of this kind of workshop, determining a useful assessment method can be a challenge. The UCSD workshop outlined here was the first part of a three-part course series, where different aspects of information literacy instruction was scaffolded over all three parts, so the consideration was whether to assess the primary source session on its own or as part of the whole series. The ultimate decision was to assess the progression of student knowledge over their three workshop/three quarter experience with the library. While it is commonly opined that assessing student knowledge directly at the conclusion of a course is not best practice, as demonstrated in Krause’s (2010) study, useful data can still be learned by doing so.

In either case, a one-shot session or a series of workshops, a formative assessment method, specifically a pre- and post-test, could offer an idea of how closely the workshop aligns with the outcomes set for student learning and if student understanding of the concepts taught in the session improved by the end of the course or course series. The question used for this assessment presented students with a list of primary, secondary, and tertiary sources, and asked students to choose which ones were primary. Data analysis included determining how many primary sources were correctly identified, which primary sources were not identified at all, and which sources were incorrectly identified. After analyzing which sources were discussed in the workshop and to what degree, and comparing that to the data, the workshop can be improved in subsequent academic years.

SUMMARY

Embedding primary source—focused information literacy workshops into first-year writing courses, individually or as part of a large-scale program, is both challenging and rewarding. It can increase student engagement and academic outcomes, and provide tools for building critical thinking skills. By using an object-based learning model to relate the analysis of primary sources to students’ previous knowledge, and asking them to use that previous knowledge to make inquiries about the sources, this type of workshop also helps students begin to question a source’s validity, context, strengths, and limitations. This ultimately helps students understand their part in the relationship between creation and consumption of information. In acknowledging these many benefits, and offering the context of the UC San Diego Library as a case study, these guidelines allow anyone to create this kind of workshop, and in doing so, foster students who are better equipped to handle the current information-rich environment.

REFERENCES

Anderson, A., Golia, J., Katz, R. M., and Tally, B. (n.d.). TeachArchives.org: Our findings. Retrieved from http://wwww.teacharchives.org/articles/our-findings/

Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2011). The LEAP vision for learning: Outcomes, practices, impact, and employers’ view. Retrieved from https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/files/LEAP/leap_vision_summary.pdf

Association of College & Research Libraries. (2016). Framework for information literacy for higher education. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/issues/infolit/Framework_ILHE.pdf

Bahde, A. (2011). Taking the show on the road: Special collections instruction in the campus classroom. RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, & Cultural Heritage, 12(2), 75—88.

Bahde, A., Smedberg, H., & Taormina, M. (Eds.). (2014). Using primary sources: Hands-on instructional exercises. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

Dhawan, A., & Chen, C. J. (2014). Library instruction for first-year students. Reference Services Review, 42(3), 414—432. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-04—2014-0006

Krause, M. G. (2010). Undergraduates in the archives: Using an assessment rubric to measure learning. American Archivist, 73(2), 507—534.

La Mesa Chamber of Commerce. (1915). A few things you should know about La Mesa: The scenic suburb of San Diego County [pamphlet]. Retrieved from http://roger.ucsd.edu/record=b6302708~S9

Library of Congress. (n.d.). Using primary sources. Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/teachers/usingprimarysources

Liu, O. L., Frankel, L., & Roohr, K. C. (2014). Assessing critical thinking in higher education: Current state and directions for next-generation assessment. ETS Research Reports Series, 2014(1), 1—23. https://doi.org/10.1002/ets2.12009

Mackey, T. P., & Jacobson, T. E. (2011). Reframing information literacy as a metaliteracy. College & Research Libraries, 72(1), 62—78.

Matthew, V., & Schroeder, A. (2006). The embedded librarian program. Educause Quarterly. Retrieved from http://er.educause.edu/~/media/files/article-downloads/eqm06410.pdf

UCL Museums and Collections. (n.d.). Introduction to object based learning. Retrieved from http://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums/learning-resources/object-based-learning

Yakel, E., & Torres, D. (2003). AI: Archival intelligence and user expertise. The American Archivist, 66(1), 51—78.