Teaching information literacy and writing studies - Grace Veach 2018

Communities of information

Classroom-Centered Approaches to Information Literacy

At many universities, information literacy is an integral part of the first-year composition course. The Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing from the Council of Writing Program Administrators, the National Council of Teachers of English, and the National Writing Project explains that one of the primary goals of college composition instruction is to encourage a “Habit of Mind” of curiosity, which

is fostered when writers are encouraged to: use inquiry as a process to develop questions relevant for authentic audiences within a variety of disciplines; seek relevant authoritative information and recognize the meaning and value of that information; conduct research using methods for investigating questions appropriate to the discipline; and communicate their findings in writing to multiple audiences inside and outside school using discipline-appropriate conventions. (2011, p. 4)

First-year writing (FYW) courses seek not only to introduce students to strong research methods, but also to help students understand the motivations for conducting research. Additionally, students learn how to frame appropriate questions for their field or topic, find and use credible sources, and synthesize their research. Since information literacy is just one aspect of composition instruction, FYW students often struggle with the complexities of information literacy given the limited amount of time for instruction. Therefore, FYW introductions to information literacy work best when thought of as a foundation that students will continue to build upon in subsequent academic pursuits.

However, for information instruction to be most useful, students need to learn how to transfer those skills into other areas. Recent composition studies have found that students have trouble transferring what they learn in one class, or even in one assignment, to the next. The Elon Statement on Writing Transfer explains that students do not think they will use the knowledge and skills from FYW courses in other areas (2013, p. 4). Writing instructors can help foster transfer by teaching concepts of composition and information literacy in context with each other as part of a research-writing process and in assignments that tie in with students’ academic interests.

Additionally, both composition and information literacy theories (ACRL Framework, 2015; Townsend, Brunetti, & Hofer, 2011) hold that threshold concepts can be powerful learning tools for students. Recognizing the centrality of threshold concepts to learning transfer, the Elon Statement says that “Once educators identify threshold concepts that are central to meaning making in their fields, they can prioritize teaching these concepts, in turn increasing the likelihood that students will carry an understanding of these core concepts into future coursework and contexts” (2013, p. 3). Linking together the threshold concepts of composition, based in the theory of discourse communities, with those of information literacy enables students to see how research and writing are bound together, and how the practices of both apply to other disciplines.

Discourse communities are formed when a group of people use language in similar ways, with shared key terms, values, and assumptions. They use this set of shared language tools to build and achieve common aims, and to communicate internally and externally about those aims. Discourse community analysis assignments ask students to use multiple methods of research to identify and explain how a particular discourse community communicates their goals. Many FYW courses employ discourse analysis as a means to teach students about composition concepts like audience and genre. Discourse analysis promotes learning transfer, giving students a strategy instead of a template, and when instructors allow students to conduct analysis on an academic or professional discourse community that they are interested in, or plan on entering, students are both more prepared to conduct research in their chosen field, and are better able to see how the strategies they learn can transfer to future writing and researching situations. By extending the bounds of discourse communities to information literacy, instructors and librarians can create powerful connections between composition and information use. We adopt the criteria for discourse communities delineated by John Swales (1990). He outlines the six characteristics of a discourse community:

1.A discourse community has a broadly agreed set of common goals (Swales, 1990, p. 24).

2.A discourse community has mechanisms of intercommunication among its members (Swales, 1990, p. 25).

3.A discourse community uses its participatory mechanisms primarily to provide information and feedback (Swales, 1990, p. 26).

4.A discourse community utilizes and hence possesses one or more genres in the communicative furtherance of its aims (Swales, 1990, p. 26).

5.In addition to owning genres, a discourse community has acquired some specific lexis (Swales, 1990, p. 26).

6.A discourse community has a threshold level of members with a suitable degree of relevant content and discoursal expertise (Swales, 1990, p. 27).

By engaging students in an analysis of a particular discourse community with which they are already connected, or with which they wish to be connected, instructors can encourage students to ask: What does it mean to enter scholarly conversations? How can I (the student) conduct research that helps me to understand and enter into the discourse community? What does the lens of the discourse community help me (the student) to better understand about the community’s work and methods of communication? How does that help me (the student) understand the information creation process and participate in it?

To make a discourse community assignment even more useful, instructors can give students the opportunity to research their choice of an academic community that they either are a part of now or are on the road to joining. For example, they might choose to conduct research on the discourse community of first-year writing courses, or first-year science courses, or they might choose to research the discourse community of the American Association for the Advancement of Science journal Science in preparation for reading, using, and eventually contributing to the research shared in that community. This approach makes the assignment relevant to students while also introducing them to the academic conventions in their field, making transferring knowledge of how to write in their field more likely.

DISCOURSE COMMUNITIES AND INFORMATION LITERACY

The artifacts of discourse (print texts, recordings, Web documents, etc.) are information, and as such fall under the umbrellas of both discourse communities and information literacy. Since the product of a discourse community is information, and in a FYW course students are both learning how to navigate and to join discourse communities, students should be taught about discourse communities and information as linked ideas. Another way to reframe the idea of discourse communities would be as information communities that share aspects of both Swales’s definition and the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education. Not only do students learn about the features of different types of communication in a given field, they begin to think of the artifacts of that communication and how it is organized, shared, and created. While the notion of linking genre analysis and information literacy is not new (Simmons, 2005), our goal in this chapter is to give examples of how to explicitly draw together some of Swales’s characteristics of a discourse community and the Framework. Here are three areas where discourse communities and information literacy overlap.

ACTIVE RESEARCHERS

Swales’s second and third characteristics of a discourse community are that it “has mechanisms of intercommunication among its members,” and that it “uses its participatory mechanisms primarily to provide information and feedback” (Swales, 1990, p. 26). In other words, in discourse communities members use agreed upon outlets to communicate with one another. For example, in academic discourse communities, those outlets are commonly conference presentations, posters, peer-reviewed articles, monographs, and, more recently, blogs and tweets. Notice how, in Swales’s definition, intercommunication is a key feature of the discourse community. In order to be considered members of a discourse community, participants must communicate with one another in some fashion. Discourse community members are not passive; they share information and make active choices about how to explain the significance of that information in ways that support achieving their shared goals.

This idea of intercommunication is at the heart of the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education frame Scholarship as Conversation, which states that “communities of scholars, researchers, or professionals engage in sustained discourse with new insights and discoveries occurring over time as a result of varied perspectives and interpretations.” Contemporary information literacy teaches that students should recognize that information often develops through dialogue, and that they are entering that dialogue with their research. For the librarian teaching information literacy in a classroom that is using discourse community analysis, this is a key component of showing how the skills learned in that analysis transfer to information literacy. In particular, the Framework also highlights the active nature of information-literate students, who “see themselves as contributors to scholarship rather than only consumers of it.” Students should understand that with their research and writing they become active participants in the discourse community.

AIMS AND FORMATS

The frame Information Creation as a Process intersects with Swales’s fourth criterion that “a discourse community utilizes and hence possesses one or more genres in the communication furtherance of its aims,” particularly in how the Framework considers format. Swales’s definition of discourse communities is in service of his larger project of laying out genre analysis, but in this particular case librarians can examine how the formats of information used in a discourse community work within larger definitions of genre. Students can map how information moves through different formats within a given community, and how those formats serve the needs of audiences within the community. Looking at format and genre provides an opportunity to teach not only traditional information literacy concepts like primary and secondary sources, but also allows for deeper exploration of how the information creation process can be shaped by the goals of the community itself. For example, in scientific communities where quick access to new information is a priority, scientists tend to publish journal articles, which allow for faster publication than monographs.

Tying together format and aims can be particularly helpful for promoting the knowledge practice that students “develop, in their own creation processes, an understanding that their choices impact the purposes for which the information product will be used and the message it conveys” (Framework). Another way of considering this would be to suggest that the purpose of the information product can determine its format. For writing instructors, too, linking together these ideas highlights the process by which information moves through different formats.

LEXIS AND SEARCH STRATEGIES

Swales’s fifth criterion for a discourse community is that it “has acquired some specific lexis,” and this is certainly one of the more challenging aspects for students seeking to join writing and research communities. Librarians regularly see how finding the right terms used to convey and retrieve information is a stumbling block for novice members of a discourse community. The Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education recognizes that students should view Searching as Strategic Exploration, and that part of that threshold concept consists of helping students develop the ability to “use different types of searching language.”

For librarians trying to emphasize the iterative nature of searching, discussing how terms are used and developed by communities can reveal how one comes to know the terms of a discourse community through the process of analyzing and joining it. Students, especially those attempting to join academic discourse communities, “try on” the language of the academy (Bartholomae, 1986). Likewise, students seeking information must “try on” different lexical terms and searching vocabulary and strategies.

CONSTRUCTING EFFECTIVE DISCOURSE COMMUNITY ANALYSIS ASSIGNMENTS

This sample assignment is a prompt for a three-part discourse community project that emphasizes information literacy by engaging students in learning about an academic community and guiding them through an iterative process of research and writing. Students conduct observations, analyze primary documents, and use their findings to draft effective interview questions. Next, they identify stakeholders in the community and conduct interviews with them. They mine the interviews for significant insights, vocabulary, and indications about the ideologies of the community. Finally, they compose a written or digital representation of their findings and the significance of their findings. Their final product demonstrates what makes the discourse community unique and serves as an introductory piece of information for people interested in entering or furthering their involvement in the community.

The three-part setup of the assignment places an emphasis on information literacy, and particularly on helping students to see how discourse communities create and use information. The iterative nature of the project empowers students to recognize how information creation is a process by asking them to engage in different types of research and to conduct research at multiple points in the project. It encourages them to see themselves as beginning researchers who are entering a scholarly field and conversation.

TAILORING AND SCAFFOLDING THE ASSIGNMENTS

This assignment can easily be adapted to serve different class needs. It can be used as a group project with a presentation aspect at the end or as a portfolio, with the separate pieces written throughout the class and revised for a final class project. The assignment could also result in a multimodal presentation, an infographic or poster, a fully written research article, and so on. Instructors can shorten an in-class or supplemental assignment by directing students to focus on only one of the six characteristics of a discourse community. Another option would be to make it an innovative full-class project to encourage collaboration—the whole class can choose a community (perhaps the campus, or the freshman class) and split the class into six groups, with each group responsible for focusing on one of the six aspects of the discourse community. The assignment can also be adapted for use in library instruction classes or interdisciplinary courses.

To further aid in learning transfer and to give the assignment higher stakes, instructors can require or recommend that students submit their analysis to an external audience. The following are just a few options that are available: Students can (1) submit to an Undergraduate Research Conference at their campus or another school, (2) submit to the journal Young Scholars in Writing, which has a special section for first-year writing, or (3) circulate their research projects to a wider audience online through a blog, website, YouTube video, and so on. There are many student-produced discourse analyses posted on YouTube that can show students how they might share their own work.

Sometimes students can feel anxious when asked to engage in such in-depth and nuanced research, especially about an academic community to which some students may not yet feel that they belong. To ease student anxieties, scaffold the assignment carefully by using some or all of the activities in order to give students confidence in their abilities. Reading Swales’s definition and characteristics of a discourse community together as a class (it is written in academic language, for an academic audience, but is short and accessible for students) and discussing the reading before assigning the project gives everyone a shared vocabulary. It can also be very helpful to show examples of discourse analysis projects from YouTube or the Young Scholars in Writing archive and discuss how these examples relate to Swales’s text and what they illuminate about a particular community.

THREE-PART DISCOURSE COMMUNITY ANALYSIS ASSIGNMENT SAMPLES

These materials can either be adapted for independent use or used to scaffold a larger assignment. In the latter case, use the materials in class or as homework assignments that students can build upon to compose an in-depth discourse analysis.

Discourse Analysis Assignment Overview

This assignment invites you to use your researching and rhetorical analysis skills to investigate a discourse community. A discourse community is a group of people who share the same goals, interests, genres, and ways of communicating: for example, a group of scholars or students in an academic field like biology or sociology, a group of workers who all work in the same office or for the same company, and so forth. To decide on a discourse community to investigate, pick a community that you are either involved in yourself or that you want to be involved in. In either case, make sure it’s a community about which you are interested in learning more. The community needs to be connected either to an academic field or a professional community.

Purpose: The purpose of this project is to practice the “habit of mind” of curiosity by engaging in research as a process and entering into scholarly conversations in your field. To do so, you will conduct research about a discourse community that you are a member of, that you want to join, or that you want to learn more about. You’ll present the results of this research in the form of a scholarly research article.

Rhetorical Situation: The primary audience for your Discourse Community Project is the academic discourse community of First-Year Writing students and teachers here on campus, and particularly the FYW students who are majoring in or interested in majoring in a program connected to the discourse community that you choose to study. The primary purpose for writing this assignment is to gain knowledge about the discourse community so that you and your reader will be better prepared to enter into the conversations in the community effectively. For example, if you are interested in entering a finance profession, such as accounting, your audience will be other FYW students who are interested in becoming accountants, and your goal will be to write an analysis that will help them understand an accounting discourse community (the language, genres, shared knowledge, information, etc.) so that both you and your reader will be able to use and create information as part of conversations in the field. You’ll also have the option of circulating your Discourse Community Project to a wider academic audience.

Assignment Part 1: Identifying a Discourse Community

Choose a discourse community and identify your primary audiences. The discourse community should be one related to a field or discipline that you are studying or plan to study, or to a profession that you are part of or wish to enter. Draw on your own interests to choose a discourse community. Then, in 500—750 words, explain why you are interested in this community, how you are connected to the community, and why you think it will be a fruitful community to study. Is this community a discourse community? Why? Does it meet the six characteristics of a discourse community? In what ways? Who is part of it? Why is it a significant community to study? How will learning more about the community, its values, its methods of communication, and the information it produces be worthwhile for you? For other students? Use 2—3 primary sources from the community to support and illustrate your explanation.

Next, in 500—750 words, identify and discuss your primary audiences. To whom will you write? What other students or student groups would benefit from learning more about this discourse community? Choose a group here on campus with whom you can share your findings. This might be students majoring in a particular field, students who are members of a professional club, or students who are interning at a specific company, for example.

Finally, draft questions that you can use to interview participants in the group. Write a list of 10—20 questions, and a 150—250-word rationale for why these are good questions, and what they will help you discover about how the discourse community functions.

Assignment Part 2: Identifying Stakeholders and Conducting the Interview

Building on what you found in Part 1 and on the research you have conducted, write a 500—700-word analysis of the people who make up the community, both generally and specifically. What groups of people are involved in the community? In what ways? How do they interact with the community? What methods do they use for communicating information? In which genres do they read or write? Which specific people involved in the community do you want to talk to? Why? What do you already know about these people? What do you hope to learn about their discourse community? Use 3—5 primary sources to illustrate and support your analysis.

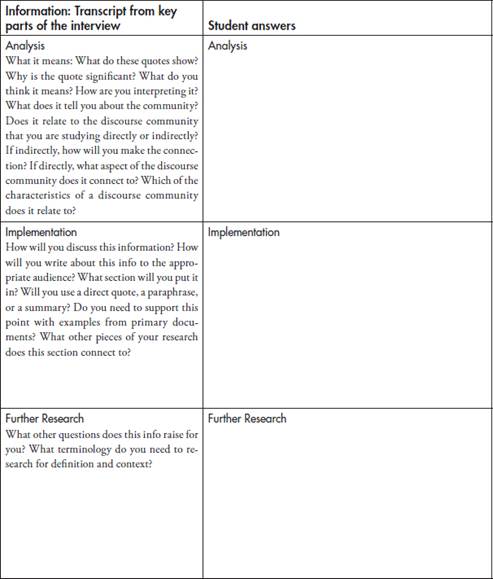

Then, choose one of these people and conduct an interview. You can use the interview questions you wrote for Part 1, but tailor them to the specific person you are interviewing. Transcribe the interview into a Word document, and complete the Interview Analysis Table (Figure 12.1).

Figure 12.1 Interview analysis table.

In-Class Activity: Compile a Lexis

Discourse communities use very specific terms to refer a given idea or thing. Sometimes these terms are the same across all communities, but more frequently different groups use different terms for the same thing or idea. For example, agricultural communities refer to a device that keeps a mother pig from her piglets as a “gestation crate,” a “sow stall,” or a “farrowing pen.” Gathering information from any retrieval system, whether it be Google, a database search, or your library catalog, depends upon knowing the terms used by your discourse community.

For this assignment, create a lexis of the key terms used by your discourse community. You should come up with as many terms as possible, both popular and specialized, and identify which of the terms you find most often used in your discourse community. It is important to note that different discourse communities will likely use different terms to indicate the same things depending on the context and intended audience. For example, where community health organizers might say “heart attack,” medical researchers will likely say “myocardial infarction.”

Generate a table that outlines the key terminology you have identified, the alternative terms for each key term, what that key term means when used by community members, and an example of use from one of the primary sources you found.

In-Class Activity: Identifying Genres and Sharing Information

Discourse communities use one or more genres to share information, build on knowledge, or make claims. For this activity, investigate what formats or genres your discourse community uses to disseminate information. For example, where does someone new to the community go to find the artifacts of discourse? Would that person go to encyclopedias, Web pages, scholarly articles, books, textbooks, documentaries, or other resources?

Compile your own mini-database (a corpus) of examples of the genre or genres used by your discourse community. Include 3—5 primary examples in your database, and write a 100—250-word discussion of why you think this (or these) particular genres are useful to the community.

Assignment Part 3: Discourse Community Analysis

Using your primary and secondary research sources, as well as your analysis of the interview you conducted, compose a 1,000-word written or the equivalent digital representation of your findings about the discourse community to help your audience understand how to successfully enter into and communicate with the community.

In your analysis, use support from primary texts and artifacts from the community, interviews with members, and secondary research to discuss how the community meets the six characteristics of a discourse community: What are the common goals of the community? The mechanisms for participation and intercommunication? How do members of the community provide information and feedback with each other? What genres do they utilize, and why? What are the key terms in the community’s lexis and what do they mean? Who are the experts and authorities in the community, and what counts as expertise? What other key things does someone who is interested in joining the community need to know in order to enter into and communicate effectively with the group?

TAKEAWAYS

Creating interwoven information literacy and composition assignments that promote learning transfer requires finding the commonalities between the two disciplines. The theories and praxis of discourse community analysis intersect with information literacy at multiple points, thus providing a wealth of options for crafting meaningful learning experiences for students. When teaching this assignment sequence in our own classes, we have seen positive development in how capable our students are in conducting research, and this is a development they have also noticed and commented on in reflective letters at the end of the course. We have also seen that teaching our first-year writing courses with a long-term, scaffolded discourse community analysis assignment helps students to think of using and creating information as iterative processes. Returning to their initial research through different lenses at multiple points in the course helps students make stronger analyses and claims. Student reflection letters indicate that they independently recognize that they are gaining authority and entering into the scholarly conversations of the discourse community. They also identify nuances of primary and secondary research materials and discover that how sources are used depends upon the context and purpose of the author. Instructors can help students become more confident information users and creators by highlighting the interconnected nature of discourse and information practices.

REFERENCES

Association of College & Research Libraries. (2015). Framework for information literacy for higher education. Chicago: American Library Association. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Bartholomae, D. (1986). Inventing the university. Journal of Basic Writing, 5(1), 4—23.

Council of Writing Program Administrators, National Council of Teachers of English, and National Writing Project. (2011). Framework for success in postsecondary writing. Council of Writing Program Administrators, National Council of Teachers of English, and National Writing Project. http://wpacouncil.org/files/framework-for-success-postsecondary-writing.pdf

Elon Statement on Writing Transfer. (2013). Elon University. http://www.elon.edu/docs/e-web/academics/teaching/ers/writing_transfer/Elon-Statement-Writing-Transfer.pdf

Simmons, M. H. (2005). Librarians as disciplinary discourse mediators: Using genre theory to move toward critical information literacy. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 5(3), 297—311. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2005.0041

Swales, J. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Townsend, L., Brunetti, K., & Hofer, A. R. (2011). Threshold concepts and information literacy. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 11(3), 853—869. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2011.0030