Teaching information literacy and writing studies - Grace Veach 2018

A cooperative, rhetorical approach to research instruction

Classroom-Centered Approaches to Information Literacy

It isn’t unusual to hear discussions among college library and freshman-year composition instructors about the “one-shot” library session. In that traditional introduction to information literacy, a writing teacher might take a day out of the planned curriculum and set the students loose in the library lab, where they learn from the library instruction specialist about navigating database choices; using key search terms, Boolean operators, and the ILL system; and saving their findings. But this approach often leaves students with the sense that research is just “looking up stuff,” rather than showing these new-to-the-university writers how research is really about inquiry, not just location, nor does the one-shot approach to information literacy instruction emphasize research as a creative behavior born of students’ curiosity and a desire to explore—and later join—existing conversations on a subject. Finally, it often does little to help students learn how to engage with these sources, or how to think of them in ways that empower students to see themselves as active, contributing participants in an emerging discussion.

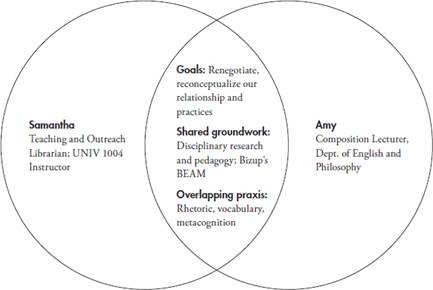

We wanted to find a better approach, one that created a shared research instructional space that incorporated a rhetorical approach toward, as well as ways to effectively engage with, the research materials found by our students. Therefore, in the spring of 2016, we set out to combine our writing and library instructional lesson planning to create more of a productive flow from the writing classroom to the library classroom and back again, lessening that silo-type feel of the previous “one-shot” model of instruction, and creating an extended, cross-classroom space informed by our respective disciplines’ key beliefs about information literacy (ACRL, WPA) (see Figure 13.1).

Figure 13.1 Collaboration Venn diagram.

Both our individual efforts as well as our collaboration were driven by the same goal: there has to be a better way than the “one shot” to teach students how to “do” research. We asked ourselves: How do we help students understand how to approach their research assignment and related search tasks as a process of inquiry, not just a quote-mining activity? How do we help our students re-see how they think about “doing research” as agency-promoting conversation exploration and building? The siloed nature of previous library instruction/writing classroom relationships has time and again proven unsatisfactory in addressing these questions. Our collaboration resulted in two tools that helped us enhance information literacy instruction through cooperative brainstorming and planning to help students think more about the why than merely the what when it comes to how they view research and source materials.

For our project, we operated from a definition of information literacy instruction as a practice that includes and incorporates the idea that research is more than just gathering bits of information. It is the search behaviors as well as how to critically evaluate and apply that found information. It is inquiry as a goal, not just a starting point, an idea shared by many scholars within our disciplines (D’Angelo, Jamieson, Maid, & Walker, 2016; Head & Eisenberg, 2009; Howard, Serviss, & Rodrigue, 2010; McClure & Purdy, 2016). We came at our individual tasks and tool development from our own disciplinary backgrounds, but we discovered that our thinking and efforts were linked by several common elements, foremost being Joseph Bizup’s (2008) rhetorical classification framework, BEAM. This created a synchronicity of effort that not only provided us with a common vocabulary, but allowed us to create a set of instructional tools based on this common text as well as the shared goals of our respective disciplinary scholarship. Further, we discovered Bizup’s work informs a variety of other library instructional publications such as Kristin Woodward and Kate Ganski’s 2013 “Lesson plan,” from which Samantha drew useful graphic summaries of core BEAM elements for her classroom session to reinforce the relationship between writing and library activities. For the writing classroom side, Bizup’s rhetorical classifications approach to source material helped set up a much-needed shift in students’ perceived relationships with sources, moving them from an extrinsic (source-as-authoritative-object external to student’s ideas) to intrinsic (source-as-dialogic-partner-in-exploration) lens through which students might see themselves in a conversation (Bizup, 2008, pp. 73, 76). Extending this into the library instruction session, Samantha created an original conceptual visual metaphor designed to emphasize student agency in this relationship—the Umbrella—continuing the use of vocabulary and concepts that center the students’ agency in relation to what their source materials do or offer them.

In our development of these two tools, we wanted to be sure we consciously and strategically created overlap and intersections made possible by existing disciplinary work. This was key to avoiding the siloed approach used in previous years, when the writing teacher simply passed the baton over to the library staff for “search instruction,” then returned to the writing classroom lessons. We wanted to create a wider, more seamless frame by renegotiating not only how we taught information literacy as library search habits, but also students’ own views of their research behaviors and—perhaps more importantly—their perceptions of and engagement with sources. Both the Umbrella and BEAM tools allowed us to “flip the lens” for students by transforming the way we talk about research and their source discoveries. The goal: to move them from seeing research and its results as a passive data-gathering performance—Burke’s “extrinsic” relationship with information (as cited in Bizup, 2008, p. 73)—toward fostering a more organic, more “intrinsic” student-idea-driven relationship with sources and research-as-inquiry (ACRL).

PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTATION: THE KEY IS A RHETORIC OF CLASSIFICATION

Our collaborative work represents important overlaps reflecting the scholarship in our fields when it comes to information literacy and pedagogy. The two-course freshman writing sequence at Auburn University Montgomery (AUM) includes a second semester focused on research writing. In 2013, the composition program redesigned the course focus and assignment arc to better facilitate a more inquiry-based approach to research, moving from several stand-alone analytical papers to a series of scaffolded projects meant to promote students’ critical and metacognitive thinking about their arguments and research best practices. These changes emerged from our work with the Citation Project in 2010. Our program was one of 17 national higher education institutions that contributed student research papers to examine how students actually integrated borrowed material into their own writing. What we learned changed our curricula, and fostered a new approach to/cooperation with library instruction specialists.

What emerged from the findings of the Citation Project for our own institution was how students perceive and use the sources they discover in their own writing. In a 2011 interview, Jamieson and Howard observed that their early stages of research data reflect on “what students are doing with their sources” (Jamieson & Howard, 2011). They remarked that most experienced academy writers believe “’research’ is about the discovery of new information and ideas, and the synthesis of those ideas into deeper understanding.” With that definition in mind, the data suggests that “the majority of the papers studied for the first phase of data analysis” failed. Only 6% of the citations are to summarized material. It is in summary that writers demonstrate comprehension of the larger arguments of a text, working from ideas rather than sentences. And in the papers we studied, students are not doing that.” The underlying premise for our post—Citation Project course revisions and composition-library collaborative efforts—that is, why students may be engaging with sources on such a shallow basis—is that our students saw source material as an external object, some thing to use in pieces. Student-perceived agency in that meaning-making relationship with sources was therefore limited. This is where Bizup’s (2008) rhetorical reframing of source material provides a way to re-see those conditions and gives us a way to help students rethink source materials and their research behaviors within the writing class and the library instructional classroom. The study’s local results for our AUM writing program clearly suggested a lack of engagement with sources’ ideas. These results not only changed our curriculum, they fostered a new approach to our cooperative efforts with library instruction specialists.

As part of our reframed approach to teaching information literacy, we became collaborative partners in developing ways to help students rethink their relationship to source materials, focusing on practices of inquiry that emphasized why and how their research discoveries were meaningful to their ideas—as opposed to simply what their sources were—to create more opportunities for metacognitive inquiry. To do this, we both relied on Bizup’s (2008) BEAM acronym as our commonplace, giving us a shared touchstone vocabulary to renegotiate this relationship.

BEAMS AND UMBRELLAS: CONCEPTUAL TOOLS TO BRIDGE OUR CLASSROOM PRACTICES

Interestingly, we discovered Bizup’s (2008) work independently. It was a happy moment of serendipity when we first met to discuss our collaborative library session planning that Samantha first mentioned BEAM as an influence on her lesson planning for my writing class’s visit. For me, BEAM had crossed my path when I was conducting research on writing programs and WPAs. Our shared path of discovery was already influencing our respective approaches to transforming praxis.

The BEAM model (Table 13.1) provided us with a clear pathway to address the disciplinary (ACRL, WPA/NCTE, and PIL) calls for a metacognitive approach to information literacy instruction. Bizup (2008) pointed out in his article “BEAM: A Rhetorical Vocabulary for Teaching Research-Based Writing” that a contributing factor in students’ troubles with engaging source material in a critical and academically accepted way is in many ways rhetorically based. As an illustration, he pointed out that our writing textbooks, library Web guides, and familiar instructional methods often rely on traditional terminology like “primary,” “secondary,” and “tertiary” to define for students what sources are (the “what”). Far too often, Bizup argued (and we agree), such labels have the power to create a rhetorical as well as relational distance between students and the source material.

TABLE 13.1 Bizup’s (2008) BEAM Classification Categories

Background/Background Source |

“Materials whose claims a writer accepts as ’facts’” (p. 75) “Noncontroversial, used to provide context … facts and information” |

Exhibit/Exhibit Source |

“Materials a writer offers for explication, analysis, or interpretation” “Exhibit … is not synonymous with the conventional term evidence, which designates data offered in support of a claim.” “Exhibits can lend support to claims, but they can also provide occasions for claims.” “Understood in this way, the exhibits in a piece of writing work much like the exhibits in a museum or a trial” (p. 75). |

Argument/Argument Source |

“Materials whose claims a writer affirms, disputes, refines, or extends in some way” “Argument sources are those with which writers enter into ’conversation’” (pp. 75—76). |

Method/Method Source |

Materials “can offer a set of key terms, lay out a particular procedure, or furnish a general model or perspective” (p. 76). |

Bizup’s article offered us a useful resource to modify instructional vocabulary to better promote the disciplinary Frameworks’ value of the metacognitive and inquiry-based approach to research. Our shared goal was to get students to think about sources differently, not approach searching as a type of “scavenger hunt” activity. Instead, we wanted them to see the sources in terms of what they do or offer. Bizup’s article provided both of us with a “new” meta language that not only functioned as a filter to help us rethink and reframe not only teaching research writing, but opened new opportunities to create collaborative instructional spaces that would become the unifying undercurrent between the prelibrary writing classroom activities, the library instructional sessions, and back to the postlibrary writing classroom. In essence, BEAM and the Umbrella became unifying thematic and practical frameworks for our collaboration.

THE “SETUP”: USING BEAM PRINCIPLES IN THE WRITING CLASSROOM AS STAGE ONE OF REFRAMING SEARCH PRACTICES AND PERSPECTIVES IN THE WRITING CLASSROOM

Why is a rhetorical approach so important to teaching information literacy? The assumption at the heart of our answer to this question is that instructional terminology has the power to shape and frame our freshman writing students’ approach to research behaviors and materials. A. Abby Knoblauch (2011) examined how composition textbooks’ terminologies frame argument and research writing by “perpetuat[ing]” a specific “version” or approach to argument (p. 248). Her survey of several well-known textbooks suggests a rhetorically framed pathway to see and “do” argument (and research) writing, one that Bizup (2008) claimed “reflects a hierarchy of values at odds with the goal of teaching writing” (p. 74). The vocabulary employed has, then, the power to shape student attitudes toward and understanding of research materials. The terms used to discuss research, in other words, can shift the power of agency either toward the knowledge product or toward the knowledge builder (i.e., the student). To help students actively engage with sources rather than simply quote mine, we wanted to emphasize the role of the builder by using vocabularies that promoted their agency. This is where the rhetorical tools of BEAM and the Umbrella graphic prove useful in helping students thoughtfully engage with content by scaffolding activities that ask them to identify the functionality of the different types of information they wish to locate.

Using Bizup’s framework, we moved the emphasis away from what the source is (tertiary, primary, etc.) to what students can do with it in their own researched argument by asking more why and how questions about the source content. Further, that lens can be flipped to become a way students can consider how their sources intended their materials to function rhetorically (e.g., Who was the target audience for such a publication? Why and how does such audience awareness affect the message?). Such considerations are key to framing the way students search and engage with these materials prior to attending the library session because of the potential to make explicit the potential for fundamental changes to the way they perceive not only their roles as researchers, but also how the knowledge offered shapes their thinking instead of what it proves. As Bizup (2008) put it, “If we want students to adopt a rhetorical perspective toward research-based writing, then we should use language that focuses their attention not on what their sources and other materials are … but on what they as writers might do with them” (p. 75).

During the early weeks of the term in the writing classroom, students work through topic exploration and preliminary inquiry activities. Prior to visiting Samantha’s classroom, students had already submitted their Topic Exploration essay, a brief informal overview of what they know and what they want to discover—largely through in-class discussions and activities that frame research as a conversation within and between discourse communities and stakeholders. These terms create a conceptual and rhetorical framework through which to see their role and the role of sources they encounter through research. The in-class readings and activities emphasize inquiry and questioning to explore their topics as complex issues, not as pro/con arguments. The principles of BEAM are introduced through guided discussion of source materials (both provided and found through early searching using online Web browsers and news services). This allowed me to “prime the pump,” as it were, so that prior to the library session, students are already using BEAM principles as a meta-cognitive lens through which to consider how sources function.

By the six-week mark, students had already received early feedback on their research ideas (their thesis admittedly still in a state of flux based on the assumption that further inquiry will help them refine their approach and thinking as they consider other conversational perspectives). Further, discussion had begun on how to evaluate source materials based on thinking of sources through the BEAM lens—what does the source do and why, not simply focusing on what it is. These discussions and early work produce materials students use to begin developing relevant key search terms (see the worksheet in the Appendix) as outgrowths of their own questions (what do they need, what do they want to do and why). The first six weeks, then, become a building phase based on focusing on the metacognitive, asking them to base their initial inquiry and exploration on questions and introducing other rhetorical factors: Who is my audience? Who is the audience of these early found materials? What is the purpose of these conversations? Why is this important to what I want to accomplish or discover? The lesson planning occurred with a conscious eye toward the upcoming session with Samantha, setting the stage for an instructional hand-off that played more like a duet than independent solo acts. This way, students were prepared for their time with Samantha, having already begun to think about their own informational goals.

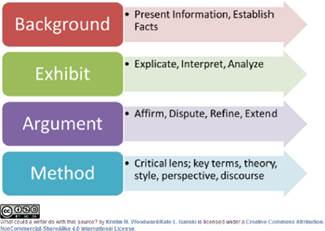

Prior to the library session, students are provided with an infographic overview of the BEAM terminology (see Figure 13.2), which is incorporated into a discussion of the kinds of information students think they will need to move their ideas forward, address their early research questions (and variations of those questions), and represent the various views and needs of others involved in this conversation (aka stakeholders).

Figure 13.2 BEAM infographic. (From Woodward, K. M., & Ganski, K. L. [2013]. BEAM lesson plan. UWM Libraries Instructional Materials. https://dc.uwm.edu/lib_staff_files/1/. Used with permission.)

Students are then guided through a close reading of one or two short sample texts to explore these four classification categories, first by modeling, then in small group exploration and discussion, and finally individual blogging in which each student applies as many as possible of the BEAM features to one of their previously identified “conversation partner” source texts. Drawing from the sample questions provided by Woodward and Ganski’s (2013) lesson plan (Table 13.2), students read a common reading text provided by the instructor and dissected it as a class. Students had a hard copy in hand while the same text was projected on the overhead screen. The guided discussion foregrounds the importance of student-centered inquiry—what do they want to know or discover about their topic—to shape the questions.

TABLE 13.2 Questions Adapted from Woodward, K. M., & Ganski, K. L. (2013). BEAM lesson plan. UWM Libraries Instructional Materials. Paper 1; and Bizup, J. (2008). BEAM: A rhetorical vocabulary for teaching research-based writing. Rhetoric Review, 27(1), 72—86

B = Background |

What information would you need to give your readers to establish key facts about [your topic or some feature of your topic]? |

E = Exhibit |

What could you analyze or interpret for your reader? Why might this be significant to your reader as you build your own claim? |

A = Argument |

What claims have your conversation partners (sources) made that you want to engage as part of building your own argument or deepening your inquiry? In other words, which of their claims do you want to agree with, disagree with, or build on somehow? |

M = Method |

How does this conversation partner (source) give you a model for a way or ways you might approach, analyze, or frame your own research question and/or contribute to this conversation? |

These lessons explicitly apply the BEAM acronym as a flexible rhetorical framework to show students how to engage with a source by asking questions about its rhetorical function from the student writer’s perspective. Our own lesson designs integrate Bizup’s (2008) explanation of such functionality: “Writers rely on background sources, interpret or analyze exhibits, engage arguments, and follow methods” (p. 76). During these close reading and group work activities, students were asked questions designed to help them think about their information needs as well as how sources might fulfill them. A few examples might be: How can you apply information provided by Source X as Background for your own ideas? What sorts of Exhibits will you want to provide and analyze to support your ideas, and how will you present or frame them? (It is important to distinguish between Evidence and Exhibit: Evidence might be seen as either/or, static proof that does not invite questioning or interpretation. Exhibits, on the other hand, require interpretation and analysis as a way to make meaning.) Why does the Argument presented in Source Y inspire you to push back or embrace its points as a way of affirming your own? How does the use of definitions by Sources L and M provide you with an example of a Method you might use to frame your own research questions? Such questions better prepare students to move into the library session because they help them see research as not just knowledge gathering, but an active engagement with and building upon others’ ideas based on rhetorical inquiry practices. These questions also provided terminology for conducting preliminary searches in Google and Google Scholar as part of exploring existing conversations about their early topic ideas. These early key terms, as well as early research question(s), were recorded on an instructor-designed worksheet, a copy of which was provided to Samantha one to two weeks before our visit, along with the most recent assignment sheet (see Appendix). The worksheet’s fill-in-the-blank prompts reflect the type of metacognitive questioning informed by the BEAM-inspired activities. This scaffolding serves as a guided note-taking device that helps not only to reinforce early research work, but to continue the common bridge between classrooms by creating a pattern of repetition picked up in Samantha’s Umbrella graphic.

The students in a freshman writing classroom often struggle with their own agency as writers and knowledge builders; both BEAM and the Umbrella as conceptual tools help them to approach their sources as more than prepackaged bits of proof requiring nothing more of them than quote mining. Bizup’s E of Exhibit is one of the more important (and often most difficult) of the tools as it requires them to take an intrinsic approach to their found material, to look at a source as more than “evidence” or “proof,” labels that frame both the sources and the students’ research behaviors as external. Many students seem to believe that they have to find sources that merely back up previously held beliefs, or they look to sources beyond their personal authority as the “real” (i.e., academically valid) knowledge builders as opposed to knowledge reporters. Such perspectives often do little to encourage students to embrace their own roles in new knowledge formation. Changing the vocabulary we use to discuss and practice research sets the stage for breaking down those perspectives. By asking students to apply this method of rhetorical classification to their thinking, planning, and search behaviors, we are asking them to consider how their sources-as-conversation-partners might add clarity, depth, and shape to their own ideas.

ON TO THE LIBRARY!

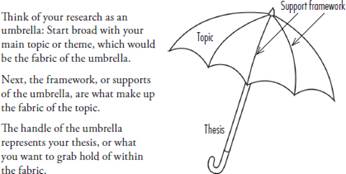

Many students, especially freshmen, struggle with research and its various components; being asked to write a paper and do research on a topic can be overwhelming. The Umbrella was created in an attempt to make the research process a little less daunting and a little more understandable for students. By breaking down a topic into its fundamental parts, students are able to go into a library database with topic-specific keywords and phrases and come back with useful and relevant sources. Research is not linear; there are lots of rabbit trails that can distract and derail students as they look for sources. Just as BEAM offers verbal/vocabulary “bumpers” (as in bowling) to help them manage the research process and their role in it, the Umbrella metaphor continues that effort into the library, offering a visual representation of their topic to help them stay on track.

The Umbrella is a fairly simple concept: the main part of the Umbrella is the fabric (the main topic), the framework of the Umbrella (the ribs) is the different aspects of the topic itself, and the handle represents the thesis or the core of the research (see Figure 13.3). For example, if a student is writing a paper on the topic of sports medicine, she would begin with the fabric of Sports Medicine, which is a very broad and generalized topic, and too big to plug into a database and expect relevant results. But by moving on to the ribs, or framework of the topic, she can begin to narrow down her topic. The framework is the sum of the parts of the topic—the questions students need to ask are: what makes up Sports Medicine, what is associated with that topic, what would someone who works in that field deal with on a daily basis, and so on. Once the students have narrowed down exactly what they want to find out about their topic, they can move down the handle. The handle represents what they want to pull out of their research, what they need to hold on to while looking for sources. If their goal in doing research is to find out more about the rate of concussions in high school football players, then they can look back to their Umbrella to find keywords, phrases, and concepts to help them in their research. In the database or some other research platform, they would start in the advanced search mode and use the broadest keyword in the first search box, followed by a narrower one, followed by another narrow keyword linked by Boolean operators AND or OR. For example: Sports Medicine AND Concussions AND Football.

Figure 13.3 The research umbrella.

This model can be used broadly for any research topic, and the process really is not very different from how most seasoned researchers conduct their own searches. However, what writing instructors and librarians need to keep in mind is that research, especially college-level research, is a foreign concept to most incoming students. They have grown up with Google, which reinforces their use of natural search language; they know they can just go to Google and ask it their questions. This approach, however, often leads to frustration when the student cannot find the scholarly, or even relevant, sources required for their assignment. This, in turn, can often lead to students changing their topic to what they feel is a more research-friendly topic, or complaining to the professor that there are no sources for their topic. Using the Umbrella and BEAM as a framework for their research changes the way students see and approach research and allows them to engage with sources on a deeper, more meaningful level. This approach allows librarians and writing instructors to help students produce better final products, as well as providing them with the tools they will need to be successful in future classes. The Research Umbrella graphic allows for more of an organic image of this process, as opposed to the more traditional linear metaphor of seek-and-find, and allows for more organic and inquiry-based thinking about doing research than the linear models that many students seem to cling to.

POSTLIBRARY: BACK TO THE WRITING WORKSHOP

The prelibrary classroom activities prime students with an introduction to BEAM vocabulary as a way to promote their engagement with source materials by emphasizing their roles as agents of knowledge building. Samantha’s introduction of the Research Umbrella and review of BEAM principles during the library classroom session reinforced this, and combined it with an introduction to rhetorically driven search practices to support student engagement. Postlibrary, the two conceptual tools were then revisited in the writing classroom’s activities and discussions, which were designed to explore how to best apply their library discoveries through more student-topic-focused BEAM-based questions. Moving forward into the research writing process, the BEAM and the Umbrella provide a powerful partnership of founda-tional concepts that offers the potential to deepen the connections between students’ own thinking, reading, and inquiry efforts and the information literacy practices (i.e., search strategies and tools) presented during the library instructional session.

WHAT’S NEXT: RECOMMENDATIONS

Our goal for this collaborative teaching effort was to help our students approach research “as strategic exploration” (“Introduction,” ACRL Framework), but in many ways we believe our approach to teaching and cross-disciplinary collaboration has been productively transformed as well. Both the BEAM’s classification and the Research Umbrella metaphors provided lexical and conceptual tools for instruction as well as our own curriculum design practices. The BEAM and Umbrella are metaphoric lenses for our roles as well as the students as researchers … this is all about reframing the approach to research and student agency in that process. These tools provided us with a “new” meta language for our instruction: BEAM provided a rhetorical lens/filter to rethink and reframe not only teaching research but also collaborative possibilities. As teaching partners, we used these two tools in planning our instructional activities to create cohesion and transfer potential through the shared concepts and language they made possible.

There is room for revision, of course. In future collaborative sessions, we plan to address several areas:

1.Consider adjusting the timing of the library instructional session earlier or even a bit later in the research project arc. In this first iteration, the library session took place five weeks into the term, after students had begun working on their second project, a critical source evaluation and annotated bibliography project. Positioning the library instruction at this point allows students to think through their ideas independent of source materials; moving the session a few weeks later might promote more source-specific connections using the BEAM and Umbrella analysis, making it more relevant to students.

2.Incorporate more information literacy instruction throughout the course, not just one assignment. One possibility is the Embedded Librarian initiative proposed by Samantha, in which library instruction specialists would come into the writing classroom a few weeks after the initial library-based session. This would allow for expanded collaborative possibilities and additional one-on-one consultation between writing students and library instructional staff.

3.Many of our freshman students at AUM are first-generation college students (over 60% as of 2015). Most are local, and perhaps under-prepared. Such categories may mirror many students who attend community colleges. This approach to collaborative information literacy instruction isn’t just for a four-year institution like AUM. It can—and should—be successfully implemented in a variety of educational settings.

In the fall of 2016, we presented our work to a regional conference. Following the presentation, several writing and library instructors remarked that the BEAM and Umbrella materials could benefit their own student populations at smaller four-year institutions as well as community colleges. Such interest confirms that there is a real desire to find innovative ways to change how we teach information literacy, and such metaphoric/conceptual tools have the potential to contribute to this need.

4.This approach has the potential to be a bridge for underprepared students who have little background in research behaviors, but also can serve those in upper-level writing-intensive courses. Future collaborative efforts will focus on tailoring our approach to the needs of both.

This collaboration served as groundwork going forward, a collaborative partnership that promises much. We will tinker and adjust, but the main goal of widening the cooperative space for writing and library instructors, with common goals and a shared set of tools/perspectives, was achieved. William Butler Yeats once wrote that “Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire.” We hope our work adds a spark to that ember.

APPENDIX. Library Day Worksheet

Complete the blanks below to help you think about the Types of Source Materials or Information you might need/want/find:

✵Key Search Terms

✵_______________________________________________________

✵Key Definitions

✵_______________________________________________________

✵Historical/Background Information

✵_______________________________________________________

✵News Based/Facts (Dates, People, Numbers, Places)

✵_______________________________________________________

✵Analysis/Argument (Perspectives)

✵_______________________________________________________

✵Types of Publications or Websites that might have information on this subject

✵_______________________________________________________

✵Audiences who might weigh in? Be interested/invested/affected?

✵_______________________________________________________

✵Record below all of the resources you find during our Library Lab time. Even if you do not use them in your paper, it’s a good idea to keep a Running Bibliography as you go.

✵_______________________________________________________

✵Record the Questions That Arise:

✵Should___________________________________________?

✵When/Where_____________________________________?

✵Why______________________________________________?

✵How______________________________________________?

✵What____________________________________________?

✵Who______________________________________________?

REFERENCES

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2016). Introduction. Framework for information literacy for higher education. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Bizup, J. (2008). BEAM: A rhetorical vocabulary for teaching research-based writing. Rhetoric Review, 27(1), 72—86.

The Citation Project: Preventing plagiarism, teaching writing. (2010). http://site.citationproject.net/

Council of Writing Program Administrators, National Council of Teachers of English, and National Writing Project. (2011). Framework for success in postsecondary writing. Retrieved from http://wpacouncil.org/framework

D’Angelo, B., Jamieson, S., Maid, B., & Walker, J. (Eds.). (2016). Information literacy: Research and collaboration across disciplines. Perspectives on Writing. Fort Collins, Colorado: The WAC Clearinghouse and University Press of Colorado. Retrieved from http://wac.colostate.edu/books/infolit/

Head, A. J., & Eisenberg, M. B. (2009). Lessons learned: How college students seek information in the digital age. Project Information Literacy (PIL) at the University of Washington’s Information School, Seattle, WA. Retrieved from http://projectinfolit.org/images/pdfs/pil_fall2009_finalv_yr1_12_2009v2.pdf

Howard, R. M., Serviss, T. C., & Rodrigue, T. K. (2010). Writing from sources, writing from sentences. Writing and Pedagogy, 2(2), 177—192.

Jamieson, S., & Howard, R. M. (2011). Unraveling the citation trail. Project Information Literacy Smart Talk, No. 8. Retrieved from http://www.projectinfolit.org/sandra-jamieson-and-rebecca-moore-howard-smart-talk.html

Knoblauch, A. A. (2011). A textbook argument: Definitions of argument in leading composition textbooks. College Composition and Communication, 63(2), 244—268.

McClure, R., & Purdy, J. P. (Eds.). (2016). The future scholar: Researching and teaching the framework for writing & information literacy. Association for Information Science and Technology (ASSIS&T).

Woodward, K. M., & Ganski, K. L. (2013). BEAM lesson plan. UWM Libraries instructional materials. Retrieved from http://dc.uwm.edu/lib_staff_files/1