Teaching information literacy and writing studies - Grace Veach 2018

Writing with the library

Lenses, Thresholds, and Frameworks

RATIONALE FOR PEDAGOGICAL INTEGRATION

The threshold-concept redesign of the ACRL Framework creates an opportunity for information literacy instructional programs to reconceive the work that happens in collaboration with first-year writing classes. Because the redesign focused on incorporating essential understandings and larger concepts of information literacy, not simply skills, it is essential for instructors—in the library and in the writing classroom—to have a shared vocabulary for discussing how students might integrate these two fields for lifelong learning. In “Reading for Integration, Identifying Complementary Threshold Concepts: The ACRL Framework in Conversation with Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies,” we argue that the publication of two documents—the ACRL’s Framework and Naming What We Know (NWWK)—has created a “kairotic moment” for information literacy and writing programs “to advocate collectively against one-off, skills-focused writing and research instruction” (2016, p. 178). In reading the documents side by side, we identified a set of complementary threshold concepts of information literacy and writing studies, which form the foundation of the multisession introduction to information literacy (IL) we discuss here. This chapter describes the integrated, multisession approach we use to teach the shared threshold concepts (TCs) of information literacy and writing studies. The pedagogical integration and complementary concepts embedded in these sessions intentionally blur the boundary between the writing program and the IL program because these boundaries must be blurred, if not fully dissolved, if students are going to embrace the necessary habits and practices that will allow them to develop as undergraduate scholars and researchers.

The multisession model described here was first piloted during the spring semester of 2015. Our initial collaboration began because both writing and library instructors felt a dissatisfaction with traditional one-shot information literacy sessions. In particular, instructors knew first-year students were not clear about how to approach answering a research question, nor did students understand why scholars ask research questions; thus, we wanted to help them build a schema for how to think about research, and TCs provided us with a way to develop this conceptual knowledge. As we have argued elsewhere, we see the TCs of writing studies and information literacy as complementary: the TCs of writing studies focus on the production of information, while the TCs of information literacy focus on the consumption of information. Thus, we advocate that through a co-teaching of shared TCs of writing studies and information literacy, students are provided with multiple entry points into developing a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness of research and writing.

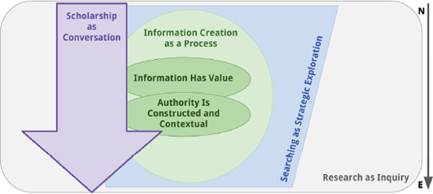

Our multisession model relies on Scholarship as Conversation as the driver for teaching the other ACRL frames because this frame, more than any other, resonates with first-year students and the goals of first-year writing courses. Students can quickly recognize the value that the metaphor of a conversation adds to their understanding of research; more importantly, the idea of research occurring as an ongoing conversation between scholars over time disrupts their misconceptions of research as simply the reporting of facts and collating of information. We also begin with Scholarship as Conversation because the other concepts are more meaningful if students have already begun to make a conceptual shift in their identities as student scholars. If students don’t believe themselves to be scholars and researchers contributing to conversations, then the remaining frames are merely skills to be applied and, subsequently, disregarded. However, if students see themselves as undergraduate scholars—as researchers expected to produce and give back to communities of practice—then we can more effectively engage them in conversations about “the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning” (ACRL, 2015). Figure 3.1 represents the relationship we see between the six frames; we’ll use this image to illustrate how Scholarship as Conversation can be a common thread, what we call a driver, for building a foundational experience for a multiyear, multicourse IL program. We do not articulate the shared threshold concepts of our disciplines here (because this discussion can be found in our 2016 article, “Reading for Integration”); however, we will describe how one frame can be integrated into first-year writing courses to reshape how students think about their work as researchers.

Figure 3.1 Making Scholarship as Conversation the driver for the remaining frames.

CO-TEACHING INTEGRATED, SHARED THRESHOLD CONCEPTS

The multisession, integrated model of information literacy instruction described here uses the information literacy threshold concept of Scholarship as Conversation as the driver around which students learn concepts and strategies for engaging in scholarly conversations through research and writing—the primary outcome for our second-semester, first-year writing course. As Figure 3.1 illustrates, the six frames of information literacy are themselves interconnected and layered. By designing instruction with Scholarship as Conversation as the driver, we are able to build a conceptual understanding and approach for research and writing first, and then we interweave other concepts of information literacy as they apply. Here we share our pedagogical design for each session in the multisession model, as well as evidence of growth from two students, Karolyn and Shelby, as they progress through the sessions.

Pedagogical Design Using Multisession Model

The multisession model is effective because it is a pedagogically integrated method of collaborative teaching. Sessions are planned collaboratively with writing instructors and seamlessly integrated into the writing course content; the design is such that activities in both the writing class and the information literacy sessions reinforce the concepts of the other. This pedagogical integration matters because the conceptual nature of our driver—Scholarship as Conversation—is meant to influence how students approach their research-based writing; therefore, our multisession design focuses on helping students write strong research questions and curate useful research sources. Our IL multisession design actually begins before students are introduced to the semester-long, inquiry-based research project sequence. This time frame, which begins in Week 5 of 15, works because most faculty are collecting the first major writing assignment (a rhetorical analysis project) and because all students participate in a fairly uniform research-proposal process:

1.Submission and approval of a research question;

2.Proposal for research design, including preliminary identification of sources and research methodology (primary and secondary data collection); and

3.Submission of an annotated bibliography.

While our multisession design, as seen in Table 3.1, draws heavily from local context and need, the conceptual elements of the four sessions, which we describe below, can be easily adapted to any first-year writing program that asks students to complete a research-based project.

TABLE 3.1 Multisession Model of Information Literacy Instruction for First-Year Writing

|

Week |

Session |

Objectives |

Assessment Collection Activities |

1 |

Literacy Strategies Inventory (LSI) |

||

5 |

1 |

→Students will build a conceptual understanding of Scholarship as Conversation. →Students will develop strategies for eavesdropping on an ongoing conversation in order to determine its focus and varied perspectives. |

IL Session 1 Reflective Writing |

6 |

2 |

→Students will develop strategies for listening to the overarching conversation. →Students will understand various ways in which information is communicated (i.e., types of sources). |

IL Session 2 Reflective Writing Searching & Metacognition Video Research Project Reflection |

7 |

3 |

→Students will develop strategies for engaging in the conversation. →Students will be able to search for relevant perspectives (sources) that pertain to their topic of inquiry (conversation). |

Research Project Proposal Report on Research Progress Inquiry-Based Research Project Postproject Reflection |

9—13 |

4 |

→Students will understand ways in which they can contribute to the conversation. |

Postproject Reflection |

15 |

Literacy Strategies Inventory (LSI) |

Multisession Objectives: An Overview

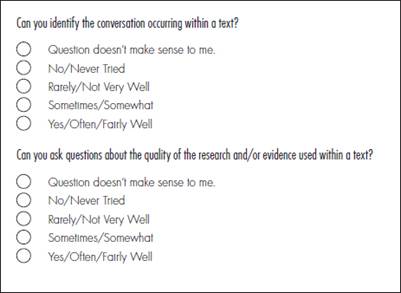

Assessing the conceptual content of these multisessions required us to identify students’ preexisting writing and research practices; to do this work, students begin the semester by completing a Literacy Strategies Inventory (LSI) (see Figure 3.2). Inspired by a writing strategies inventory designed by Betsy Sargent for the University of Alberta Writing Studies Department, this revised inventory helps students reflect on their attitudes toward their writing, reading, and research processes as well as their understandings of key concepts related to writing studies and information literacy. There are seven sections to the inventory (including Reading Practices; Getting Started, Drafting, and Researching; and Writing Processes), and each Likert-scale question offers 5 possible responses. When students complete the LSI at both the beginning and end of our courses, it helps students assess what they have learned and what goals they might have for further learning, and the LSI responses give library and writing instructors information that can help us track student progress, especially when analyzed alongside reflective writing assessments. Data from one year of multisessions shows a difference in students’ pre- and postmean scores for our information literacy—specific questions.

Figure 3.2 Sample Literacy Strategies Inventory questions.

Session 1: What Is a(n) (Academic) Conversation?

Prior to Session 1, students engage in readings in the writing class selected to prime the discussion of our driver, the concept of Scholarship as Conversation (see Table 3.2). For example, in Week 1, writing instructors assign Karen Rosenberg’s “Reading Games: Strategies for Reading Scholarly Sources,” a reading that challenges students to “read smarter, not harder” (2011, p. 211), an idea that she explicitly connects to “Joining the Conversation,” one of her section headings. Pedagogically, this reading assignment fits into the student learning objectives of the writing class because it offers an architecture for reading scholarly texts. For the multisession design, it plants a seed in the writing classroom and in the students’ discussions about how and why sources are used. As Rosenberg argues,

Even though it may seem like a solitary, isolated activity, when you read a scholarly work, you are participating in a conversation. Academic writers do not make up their arguments off the top of their heads (or solely from creative inspiration). Rather, they look at how others have approached similar issues and problems. Your job—and one for which you’ll get plenty of help from your professors and your peers—is to locate the writer and yourself in this larger conversation. (2011, p. 212)

TABLE 3.2 Session 1 Activities and Assessment Table

|

Writing Class Activities |

Session 1 Activities |

Assessment |

Karen Rosenberg’s “Reading Games: Strategies for Reading Scholarly Sources” |

3 different video clips during which students note topic, terminology, interesting points, questions Whole-class discussion to identify common threads, differences, etc. in videos Discussion question: What does this idea of “Scholarship is a Conversation” mean for you as student researchers? |

Writing Class LSI Rhetorical Analysis Assignment IL Session Reflective Writing 1 |

By introducing the idea of conversation to students and connecting it to how they are reading research-based work, the students are exposed to the concepts of Session 1, during which they will explore their connection as student researchers to the idea of Scholarship as Conversation. Furthermore, by asking instructors to complete a series of pedagogically integrated and scaffolded activities, such as these connected readings, we are removing the plug-and-play baggage that comes with the more traditional one-shot sessions. Too many faculty felt that the previous IL sessions were identical, semester after semester and year after year. But, when the writing faculty have an active role in the vertical integration of concepts across a curriculum, they are invested in co-teaching the material because the intellectual payoff for students is more apparent.

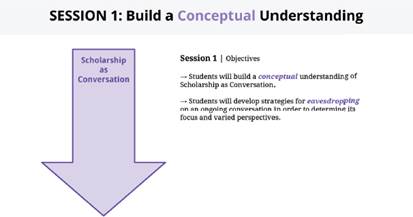

During Session 1, students wrestle with the concept that research is ongoing and happens when scholars in a particular discipline engage in conversation with one another over an extended period of time (see Figure 3.3). Students engage in an activity in which they are inserted into the middle of a conversation with no context and must develop strategies (such as paying attention to specific cues like terminology or big ideas) for determining the overarching topic of the conversation, as well as understanding how various perspectives shape that conversation. The session ends with a reflective writing assessment in which students must consider how the idea of Scholarship as Conversation changes or shapes their approach to research (see Box 3.1). Because TCs cannot be assessed on skills alone, these reflective writing prompts capture emerging shifts in student thinking and form a baseline for assessing individual growth and understanding.

Figure 3.3 Session 1 overview.

BOX 3.1

SESSION 1 IL ASSESSMENT: REFLECTIVE WRITING 1 QUESTIONS

1.How does understanding this idea that scholarship is a conversation set the stage for the research that you are about to undertake?

2.How does a conversation (instead of a procon debate or for-against positions) change how you think about research and what you will need to do differently?

When asked “How does understanding this idea that scholarship is a conversation set the stage for the research that you are about to undertake?” Karolyn notes that the concept “sets the stage for a more open-ended stance” for her research. She explains that in her high school “scholarly sources and articles were ’kept under glass’ and ’served’ rather than ’used.’” Here, she quotes an article read in the writing class (Elbow, 1995) and references the IL session, citing both explicitly: “This introductory unit [in the writing class] and the activity today have helped me understand that the research we will be compiling and incorporating in our writing is dynamic and part of an ongoing discussion with multiple perspectives.” By linking the content of the session to the content of her writing class and connecting each to her research strategies, Karolyn reveals the power of the complementary threshold concepts and the pedagogical integration of our sessions.

For Shelby, the value of Session 1 comes in understanding how to reshape her thinking about research. Rather than feeling pressured to immediately contribute to a conversation, Shelby notes that she must first “see [herself] as an eavesdropper on the conversation of scholarship for the research project [she is] about to undertake.” Before she can make a contribution, she must begin by “listening to and understanding what other people have to say about it.” Shelby goes on to describe this eavesdropping as preparation: “In some ways this would be preparing myself to enter the conversation by getting all the other perspectives and ideas that are already out there so that I can eventually contribute something new.”

The second reflective question from Session 1 focuses on conversations: “How does a conversation (instead of a pro-con debate or for-against positions) change how you think about research and what you will need to do differently?” When explaining how the concept of a conversation changes how she thinks about her research, Karolyn shifts away from taking sides: “Instead of seeing an issue as having black and white ’sides’—which is often convenient but not fully investigating an issue—a conversation allows for more than one or two perspectives and ’takes’ on issues.” We also hear emerging changes in her understanding of the purpose of research. Karolyn no longer believes she and her colleagues are supposed to be “writing our point (our argument) and the refutation of the opposition.” They are expected to “take into account all sides of a conversation that’s more of a round table than a rectangular one with two opposing heads.” For her work, Karolyn acknowledges that she will have to “branch out more when doing research, to try to bring multiple perspectives of the issue into [her] writing rather than just present [her] argument and refute the ’opposite’ side.” This is a sentiment echoed by Shelby, who notes that the driver makes “the project less intimidating to see scholarship as a conversation as opposed to an argument or debate.” She, too, will bring a more “open mind because there isn’t pressure to ’pick a side’ or pressure to prove that one side is right or wrong.” Instead, Shelby believes she is supposed “to listen to what’s out there.” In this reflective writing, we see how students’ perceptions about what they should and should not be doing are shifting as they head into Session 2.

Session 2: Listening to an Academic Conversation

Session 2 occurs approximately one week after Session 1 and focuses on moving students beyond eavesdropping on conversations by offering specific strategies for listening to a conversation in order to develop narrowed, focused research questions that will guide their process of inquiry (see Figure 3.4). Between Sessions 1 and 2, students discuss readings and engage in activities in the writing class that focus on the development of guiding research questions—for example, these activities help students further explore the purpose of a research question and the importance of presearch in helping shape research questions and give them opportunities to collaboratively workshop research questions (see Table 3.3).

Figure 3.4 Session 2 overview.

TABLE 3.3 Session 2 Activities and Assessment Table

|

Writing Class Activities |

Session 2 Activities |

Assessment |

Bernice Olivas, “Cupping the Spark in Our Hands: Developing a Better Understanding of the Research Question in Inquiry-Based Research” Randall McClure, “Googlepedia: Turning Information Behaviors into Research Skills” |

Review student reflections from Session 1. Build visual model of Scholarship as Conversation. Opening discussion question: In what mediums is information communicated? Outline characteristics of sources. Closing discussion question: What types of sources might you consult for presearch? What types of sources might you consult to gather specific, or more focused, information? Offer strategies for presearch and narrowing a topic. |

Writing Class Research Project Reflection IL Session Word Clouds Reflective Writing 2 Searching & Metacognition Video |

During Session 2, students first consider factors that contribute to the creation of different information formats, such as the characteristics of the writing style, the authority of the author, the audience, the purpose, and where the information can be accessed. Students then use this foundational understanding to develop strategies for presearch, a term taken from a writing class reading that means selecting sources appropriate for building context for (listening to) a conversation, which they then implement after the session in order to narrow the focus of their research. At the end of Session 2, students again reflect on the content of the IL session and its role in the work they must complete in the writing class. When asked “How do you plan to apply what you learned today to narrow your research topic and further engage in the conversation?” Karolyn has a clear research strategy informed by our conceptual driver. She notes that her “entry-way into the conversation will be through Google and Wikipedia, just like many students.” She goes on to note that because the session focused on “displaying all of the possible sources we could use on the board,” she will also likely use “magazines, news, blogs, websites, videos, and all sorts of other more ’informal’ sources to listen to the conversation and gather background. In order to narrow my research topic, I’ll need to have this background to go from.”

After Session 2, students may participate in an optional Searching & Metacognition Videos activity. Inspired by the LILAC Project and designed to capture their initial presearch behaviors, this assessment (which also serves as a valuable pedagogical learning tool) requires students to screen-capture the first 15 minutes of their presearch practice and narrate their behaviors and the reasoning behind those behaviors. By combining the reflective writing from Sessions 1 and 2 with a metacognition video, we can compare students’ information-seeking behaviors with self-reported data as they participate in the multisessions. We can see what strategies students bring into the class for listening to conversations and which recommendations they adopt for their research projects. As the students describe what they are doing and why, they reveal not only how complicated assessing the Scholarship as Conversation frame is and why teaching for concepts cannot be stripped down to skills-based assessment measures, but also how we can learn more about what students are learning when we watch the videos in light of reflective writing.

Karolyn, for instance, does what she reported in her reflective writing. She starts in Google because she is “not quite sure how [she is] going to word [her] question,” and she hopes “maybe [Google] will help.” She types in her topic (“creativity in scientific writing”), and then does the “cliché thing” and selects the “first link.” Karolyn immediately identifies the type of source she’s located, noting that the first link “looks like it’s an academic journal.” Her next click is on a Scientific American article, which she chose “because it seems like a reliable source.” She explains, “It is maybe more of an informal magazine or news source.” After identifying key words she wants to look up later (“dissertation chapters”), we see Karolyn organize her research, as seen in Box 3.2, creating a research folder and a separate presearch file into which she copies and pastes links to her sources; she also identifies the type of media she has located, something she might not have done without Session 2.

BOX 3.2

KAROLYN’S SOURCES LOCATED WHILE RECORDING METACOGNITION VIDEO

http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/urban-scientist/science-writing-academic-creative/

✵dissertations = projects we complete? (explore further)

✵science blogging = place in academia?

✵BLOG/more INFORMAL

MUNDAY LIBRARY

https://login/ezproxy.stedwards.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login/aspx?direct=true&db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.40186599&site=eds-live&scope=site

✵creativity, spirituality, awe, and wonder

*ACADEMIC JOURNAL

Like Karolyn, Shelby starts her resource search in Google because she wants broad terms to narrow down. She is conscious enough of Google’s sponsored links to jump down before opening a source, and just as she explained in her reflective writing after Session 1, she’s not looking for definitions or a single answer. Instead, she repeats the conceptual ideas of Session 1, looking for sources “kind of based on” her larger question. This may explain why Shelby quickly moves from search terms to a question, and in skimming through her sources, she, like Karolyn, begins making choices based on media types. One source references a poll, and we learn that she thinks this kind of information could be useful (although we don’t know why). She also creates a digital repository, bookmarking pages to a folder as she surfs. Like Karolyn, we hear how she is refining and complicating her question and how she is using methodological information in the sources to assess their relevance and credibility.

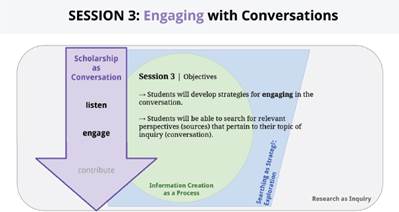

Session 3: Engaging in an Academic Conversation

By the time students participate in Session 3, they have engaged with Scholarship as Conversation on a conceptual level and experimented with different strategies for finding sources relevant to their research question. Session 3, then, provides students with more narrow strategies for engaging in a conversation through developing an understanding of how to find specific perspectives that pertain to their questions. This is the most conventional IL session because it is the first time students rely on library resources for locating information. Students create a concept map for their questions and consider relevant presearch that is helping their conversation take shape; then, the session focuses on helping students understand concepts articulated in the IL frame of Searching as Strategic Exploration, and the students workshop to dive deeper into their research. For example, we may discuss refining search terms based on date or source type.

For Session 3, there are no information literacy—specific assessments because the success of these sessions can best be seen in the final research projects completed by students (see Figure 3.5). For example, the students completed a final reflective writing assignment for the writing course in which they were expected to explain which strategies and processes from the preceding weeks contributed to their knowledge about writing and research in higher education. To complete this assignment, students were expected to “point to particular strategies [they] used during the researching, drafting, and writing process.” In her reflection, Shelby notes that she changed her major during this process, a choice that affected her initial research question; she does list the metacognition video as one of the “exercises [that] got [her] thinking about research questions and methods which was helpful when [she] went back and found new sources for [her research proposal].” Karolyn also experienced a significant shift in her project during the IL process. She notes in her reflection that she was able to “find a few sources about the role (or lack thereof) of creativity in scientific writing,” but she also notes a limitation. “Before [she] even read the sources,” she could articulate an answer to her question. Because the IL sessions focused on contributing to conversations, not merely reporting what she already knew, Karolyn knew a change was required: “Because I felt I already knew the answer, and having read Olivas’s (2009) paper on student inquiry-based research, I knew that going forward with my original question would basically be a waste of my time since I wouldn’t truly be learning or gaining anything in the process.”

Figure 3.5 Session 3 overview.

TABLE 3.4 Session 3 Activities and Assessment Table

|

Writing Class Activities |

Session 3 Activities |

Assessment |

Concept Mapping Activity: Consider the Conversation Students reflect on presearch strategies and results Introduce strategies for refined searching and synthesis of conversations Hands-on workshop with institutional resources |

Inquiry-Based Research Project, including Research Project Proposal Report on Research Progress Postproject Reflection |

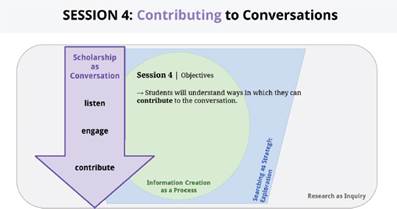

Session 4: Contributing to an Academic Conversation

The final session in this multisession model of information literacy instruction prepares students to contribute to the scholarly conversation in which they are engaging (see Figure 3.6). Session 4 is flexible in that writing instructors can choose the option that best fits the specific needs of their students, and on our campus, there have been two popular versions for this final session of the semester. Session 4a (see Table 3.5) focuses on helping students understand what to contribute to an ongoing conversation, which is why Session 4a occurs as students are preparing the final drafts of their research projects (and beginning to think about their final assignment of the term). The session touches on the frame of Research as Inquiry and includes activities that help students synthesize their research in order to identify gaps; these gaps can then be addressed by either revising the research question and reiterating the process of searching or by using the gap as an entry point into the conversation and “filling” it with a new perspective.

Figure 3.6 Session 4 overview.

TABLE 3.5 Session 4 Activities and Assessment Table

|

Writing Class Activities |

Session 4 Activities |

Assessment |

Session 4a Analysis of how sources connect to question and to each other with two (2) end goals for further research: 1.students identifying gaps in research → revising question, or 2.students identifying gaps in research → entry point into conversation. Session 4b Examine “remix” of a book in three genres Discussion: conventions, purpose, audience, selection of content |

Postproject Reflection |

In contrast, Session 4b focuses on helping students understand how to contribute to a conversation. This “how” session occurs after students have completed their formal writing project. This version of the session returns to the frame of Information Creation as a Process, as students reconsider ways in which information is created and apply that understanding to create a “remixed” version of their academic paper.

Both Karolyn and Shelby participated in Session 4a, and their writing class included a reflective writing prompt with the final project submission. The reflective prompt included questions about the students’ audience choice, process-based decisions, and, for the purposes of our multisession design, research process questions (see Box 3.3). For Karolyn, the research for this project—a remixing of her research project into three new genres for a nonacademic audience—was more “supplemental,” but there is a key practice she picked up from the multisession experience: the “info literacy skill of refining and reframing [her] search questions and terms.” She unsuccessfully searched for “statistics about students and scientific writing,” but she successfully filled in her own knowledge gap with “some troubleshooting research with the platform for [her] video genre” when she couldn’t make the voiceover work properly. She made these adjustments because the sessions focused on concepts, not skills; in fact, Karolyn even “adjust[s] the location of where [she] conducted searches (from library to outside databases to Google Scholar to Google) and what types of search terms [she] was using.” She explains, “After accepting that I wasn’t going to get any data or statistics, I decided to move into a gap in my research I hadn’t previously considered: reasons why scientific writing is ’boring’ (e.g. why aren’t fluffy words okay to use).” She was not frustrated by the adjustment. Quite the opposite, in fact. Karolyn does not treat her research process as a seek and find activity; instead, she moves “on to another gap or exploration pathway in order to be able to find information that was relevant and useful.”

BOX 3.3

WRITING CLASSES’ POSTPROJECT REFLECTIVE WRITING QUESTIONS ABOUT RESEARCH PRACTICES

1.What kind of research did you do for this project? How was it different from what you did for [the inquiry-based research paper]?

2.What information literacy practices did you use to help you adapt your existing research to your selected audience?

3.What adjustments did you have to make to your strategies to find appropriate support?

Like Karolyn, Shelby wanted a particular kind of research to fill in her gaps; more specifically, she “tried to find some sources that had statistics about first-year writing practices but unfortunately had no luck.” She, too, strayed “from trying to do traditional academic research,” and, like Karolyn, she knows this is acceptable “because it just didn’t seem to fit into [her] genres.” She also completed research related to the genres she was creating in this final assignment. She “was mostly just looking for examples for the types of genres [she] wanted to create,” which became “templates” she could consult to identify “what moves” she was supposed to make.

CHANGING PERCEPTIONS OF RESEARCH AND WRITING

Teaching first-year writing students a complementary threshold concept, Scholarship as Conversation, from two disciplinary perspectives through a multisession model of pedagogical integrated information literacy sessions is creating subtle changes in how students on our campus perceive research-based writing in higher education. Our combination of assessments—specifically the pre- and postinventories, reflective writing assignments, and metacognition videos—have captured evidence of students’ shifting schemas. For example, in the closing paragraph of her reflection for her major research assignment, Karolyn wrote the following:

Through this process I also gained insights into the research process: there won’t always be secondary sources that directly address your inquiry or exact topic, but you can always use those to help you enter the discussion, gain background knowledge, or they may be related your topic indirectly.

She is a first-semester freshman who left the multisession experience articulating the idea that research is a conversation; this is a conceptual shift for Karolyn, especially if we consider that during Week 1 of the semester she chose “Yes / Often / Fairly Well” when responding to “Can you identify the conversation occurring within a text?” on the LSI. When responding to “Can you ask questions about the quality of the research and/or evidence used within a text?,” she opted for “Sometimes / Somewhat,” but she was not among the students confused by these questions or perspectives.

The complementary TCs of information literacy and writing studies are complex, and integrating them into two programs requires pedagogical collaboration because the Framework cannot be reduced to rote skills or standardized learning outcomes. As our data from teaching the TC of Scholarship as Conversation suggests, students wrestle with this concept in increasingly complex ways as they progress through their research-and-writing projects. Their understanding organically develops as the integrated, scaffolded instruction aims to meet them where they are. Our instructors knew the timing of the traditional one-shot sessions was wrong, as too many students were sitting in sessions before their research projects were even assigned; more importantly, we realized students were not ready to look for sources because they did not understand the larger purpose: research is about joining an ongoing conversation and contributing something back to a community. The multisession experience we have designed for first-year writers starts with this premise; using the idea of a conversation as the driver, we are able to bring students into the research experience rather than positioning them as mere reporters on the sidelines.

REFERENCES

Adler-Kassner, L., & Wardle, E. (Eds.). (2015). Naming what we know: Threshold concepts of writing studies. Boulder, CO: Utah State University Press.

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2015). Framework for information literacy for higher education. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Elbow, P. (1995). Being a writer vs. being an academic: A conflict in goals. College Composition and Communication, 46(1), 72—83. https://doi.org/10.2307/358871

Johnson, B., & McCracken, I. M. (2016). Reading for integration, identifying complementary threshold concepts: The ACRL Framework in conversation with Naming what we know: Threshold concepts of writing studies. Communications in Information Literacy, 10(2), 178—198.

Olivas, B. (2009). Cupping the spark in our hands: Developing a better understanding of the research question in inquiry-based writing. Young Scholars in Writing, 7, 6—18. Retrieved from http://arc.lib.montana.edu/ojs/index.php/Young-Scholars-In-Writing/article/view/142/98

Rosenberg, K. (2011). Reading games: Strategies for reading scholarly sources. Writing Spaces, 2, 210—220. Retrieved from https://wac.colostate.edu/books/writingspaces2/rosenberg--reading-games.pdf