Teach like a champion 3.0: 63 techniques that put students on the path to college - Lemov Doug 2021

Technique 14: Own and track

Check for understanding

One morning a few years ago I stopped in on Bryan Belanger's math class. Bryan had given his students this problem to solve:

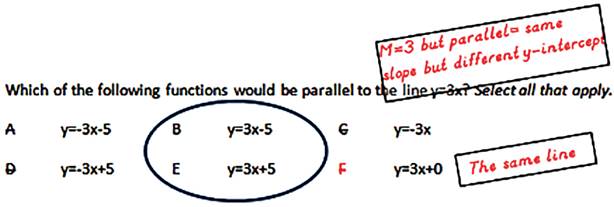

Which of the following functions would be parallel to the line y = 3x? Select all that apply.

He Cold Called students to name the correct answers, and most students understood the problem very quickly and eliminated A, C, and D, though one or two chose A as the correct answer, so Bryan quickly reviewed: “What must every answer need to have to be correct?” he asked.

“A slope of 3,” a student replied, so Bryan annotated the problem, writing “m = 3” above the prompt and asked his students to do the same. He didn't want to just correct the understanding, he wanted them to have a record of it.

Then Bryan challenged his students. “Actually,” he said, “one of the three other answers is also not correct. Can anyone tell me which one and why?”

He took hands here, and one of his students observed that “F had the same slope but also the same y-intercept.”

“Yes,” Bryan said. “That's subtle but important. It's the same line and a line can't technically be parallel to itself.”

Then again Bryan locked down the teaching point through mark-up.

He asked students to be sure to cross out answer F in their packets and to write in the margin “same line” so they remembered not only that F wasn't correct but why. Then he had them add a note so that above parallel they wrote: “Same slope but different y-intercept.”

Thus in the end students had in front of them a perfect record of what they'd learned. It looked something like this:

Bryan's actions were intended to increase the value of the time he spent studying common errors by making sure that students took careful note of what they learned. They knew not only which were the right answers, but which one had fooled many of them and why. And they had the rule as they now understood it handy for easy review. That's the idea behind Own and Track. If you're going to invest time studying mistakes, make sure students get the most out of it by “owning” the learning and tracking it.

Studying mistakes can be powerful but it's not without risks. It can lead to confusion on the part of students. They could walk away unsure of which part of the discussion was correct, with the muddled and confused memory that there were lots of ways to be wrong, but, hmmm, which was right? In fact, there's research to suggest that discussing wrong answers can result in students, especially the weakest students, failing to differentiate correct answers from incorrect ideas and merely remembering even better the errors you describe. One study found that “incorrect examples supported students' negative knowledge more than correct examples.” Error analysis benefited only students who had a strong working knowledge of how to arrive at the answer already, and students needed an “advanced” level of understanding before they were ready to benefit from analyzing errors. For other students, it actually made things worse! Now that is a note of caution!

An additional way in which error analysis can go awry would be that you invest a ton of time studying mistakes and students just don't attend to it very intently. The cognitive scientists Kirshner, Sweller, and Clark point out that any lesson that does not result in a change in long-term memory has not resulted in learning. A terrific discussion is important to building understanding but hasn't achieved learning yet. Students have to remember it. Thus, the more time you invest in studying error, the more important it is to end with students having a written record of key insights, terms, and annotation. They need a record of what they've learned both to refer back to later and to build their memory as they go by, causing them to engage with the intention of remembering. These kinds of activities are part of the final CFU technique, Own and Track.

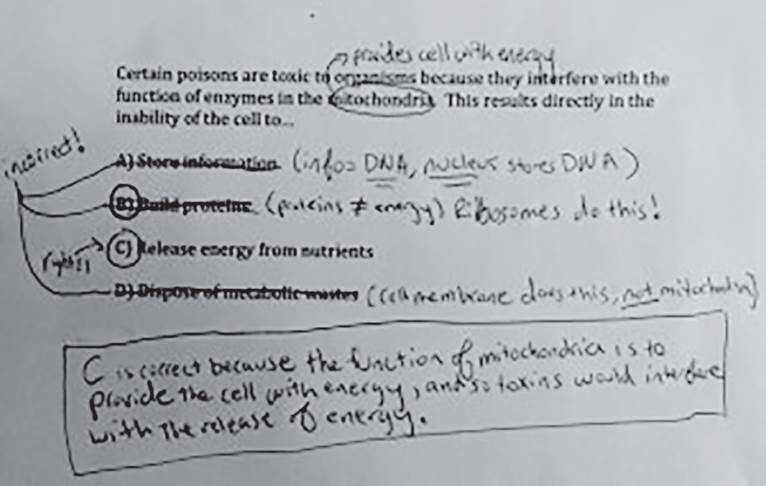

We will distill this Own and Track process down to three possible steps that teachers can encourage students to follow:

1. Lock in the “right” answer in writing.

Make sure at the end of your error analysis that students know what the right answer was.

2. Get “meta” (metacognitive) about wrong answers.

Have students take notes on why wrong answers were wrong. That's often where you spend most of your teaching time. It's immensely valuable because it's a window into students' confusion. But as we know, forgetting happens fast. They should track the learnings so they can review them later and be more likely to remember them.

3. Get “meta” about the right answers, too.

It's also useful to have students make notes on why correct answers were correct.

Below you can see an example of all three from science teacher Vicki Hernandez's class. Her class was discussing photosynthesis.14 As you can see, the right answer is clearly marked. And in the box the student has explained to herself why that answer is right. She's also explained why each wrong answer is wrong. This is a student with deep understanding of the question and a record of it for future reference.

In the video Vicki Hernandez: Let’s Make a Note, Vicki starts with appreciation for the student whose work she has Show Called, praising him for correcting his own answer. She also has the work clearly displayed on her document camera, so the students can see Vicki make notes on the correct answer. She's seen that the common error was a confusion around grass, so she asks them to lock in what they learned about what confused them. “Grass,” she says (and writes), “is a producer because it is a plant and goes through photosynthesis.”

Own and Track is a critical time for Circulation and Active Observation, as you provide time for students to explain the right answer, appropriately denote the wrong answer, and label their errors. You'll see that in Vicki's clear scan at the end of her clip—she knows the bit of information about grass is critically important for her students, and so she takes the time to make sure everyone has jotted it down.

Another way to help students engage with the content as they correct their answer is to have them reflect on the steps that they did (or did not) take, as Paul Powell did at the end of the video Paul Powell: Show Call. Paul and his students have established the correct answer for a multiple-choice question. “Are you showing your work even on a multiple-choice question?” he asks. “Pick your pencil up and give yourself a check for each one of these steps.” By building in this written reflection for students, Paul not only ensures they walk away with a clear understanding of what is right (and what is wrong); he also guarantees that their papers reflect the process they took to arrive at the accurate answer; a valuable engagement task turns into a record of lasting value. Some things you could say to help students Own and Track include:

· “Give yourself a check for every one of these steps that you got correct. If you're missing one, make a note to yourself.”

· “Circle answer B and write a margin note that explains that it uses the wrong operation.”

· “Draw a line through the [insert grammar mistake] and rewrite it correctly in the space in the margin.”

· “Make your paper look like mine.”

· “Reread your response. Add at least one piece of evidence from our discussion to better support your answer.”

· “I'm coming around to check that you've defined fortuitous in the margin and that your definition includes the word lucky.”

You can see the benefit of this written record of learning in action in the video Jon Bogard: Back to Your Notes. After a robust conversation trying to determine the nature of a classmate's error, a student, India, has the chance, as Jon puts it, to “arbitrate.” To determine who is wrong and who is right, she refers back to her notes—with great glee, I might add—to prove that her conclusion is correct. (Don't miss the snaps of support from her classmates, which validate India's scholarly engagement and the high-five from the student in front of her after she drops her evidence on the class.) Here we see the long-term benefit of a clear Own and Track system. India is able to engage in this analysis independently because she has referred back to notes that she took the previous day. Then we see the system in action: Jon says to his students, “Fifteen seconds, back to your notes, update what you had before in light of what India just said.” He capitalizes on the moment of her insight by asking every student to record it, both increasing the chances that they will remember it and creating a record of it that they will be able to refer back to.

Lessons from Online

Some of our greatest lessons from remote and online instruction have to do with Checking for Understanding. The video Sadie McCleary: Get You There, for example, is an exceptional example of how to create a Culture of Error online. The first thing you'll notice is that the video is a montage of tiny moments from one of Sadie's chemistry lessons at Western Guilford High School in Greensboro, North Carolina. Culture of Error is built up through the aggregation of tiny moments from throughout your lessons. It's a seasoning you are frequently shaking on the meal. But if AP Chemistry is challenging in the classroom, it's exponentially harder when learned on your laptop. Sadie normalizes the struggle constantly and gracefully. She asks Sierra to explain the impact of solution B on reaction rate from a slide she's projecting. “I'm going to be honest, Ms. McCleary,” Sierra replies. “I'm so confused.”

“That's OK,” Sadie replies, but then continues, “I'm going to ask you a couple of questions to get you there—because I know you can get there.” Her tone is steady and without judgment. She expresses her belief in Sierra. And then they get to work. So much of what students are responding to when they develop a sense of trust in a teacher, my colleague Dan Cotton observes, is the teacher's competence. Sadie is calm and confident when she finds that the material is difficult for Sierra and she reminds Sierra that it's a struggle, not a crisis—they'll get to work and solve the problem.

Later in the lesson Sadie is more proactive. “Finding the units for K is always the hardest skill of this unit and if it feels tricky that's OK … we'll continue to practice it.” She's reminding students beforehand that parts of chemistry are difficult—for everyone—and that they don't need to respond to difficulty with panic or frustration but with steady diligence and the willingness to practice.

Later again in the lesson Sadie asks Kendall to explain how to get the exponent in an equation. Kendall's answer is wrong, but Sadie's first words are telling: “I'm glad you said that. That's not why. That's not where we get our exponents, but Kendall has lifted up something that is a common mistake. The coefficients do not matter … you have to use your concentration data, and we're going to keep practicing that.” Earlier I noted that one key to building a Culture of Error was to diffuse defensiveness and anxiety about mistakes while still making it clear that mistakes were mistakes. Sadie does that beautifully here. It's a useful answer, she notes—she's glad Kendall offered it—because it's wrong. Sadie's management of her tell is impeccable: She's warm and supportive and unflappable. Her first words are of appreciation and then she gets down to explaining the useful lesson of Kendall's answer.