Teach like a champion 3.0: 63 techniques that put students on the path to college - Lemov Doug 2021

Technique 53: Radar and be seen looking

High behavioral expectations

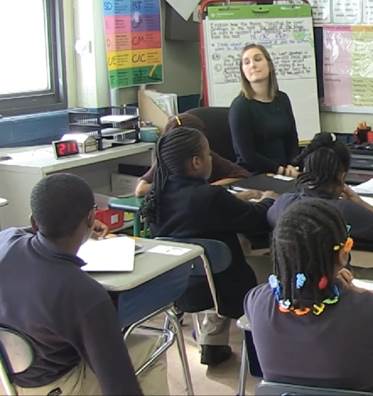

In technique 52, What to Do, I shared a video of Arielle Hoo giving directions to her math class (Arielle Hoo: Eyes Up Here). She’s a model of clarity and her students respond beautifully, working attentively, thoughtfully, and contentedly.

You can get an even clearer sense of the culture of Arielle's room in the video Arielle Hoo: Keystone, taken from the same lesson. Notice two very simple but very important things she does after giving her directions: “Eyes up here in four … three …”

I've cut and pasted a series of still shots taken from the video here and numbered them one through four to show what she does a little more clearly:

The first thing Arielle does is to look. She gives her directions and, instead of looking down at her notes or at the board, she takes a second to scan the room, right to left. This lets her confirm that students are following her directions. If they're not, she'd want to adjust. Perhaps she wasn't clear enough and she'd want to regive her directions with a bit of assuming the best: “Whoops, let me be a little clearer… .” Perhaps they're a little giddy and she'll want to slow her voice slightly to set a calmer tone. For sure, she won't want to push on too fast if students are showing signs of distraction. Either way, the lesson is that a teacher can manage only what she sees so actions that allow you to see more clearly and comprehensively are critical. Actions that allow teachers to see well constitute a critical set of skills and one that is too rarely talked about. I call such actions Building Radar.

To return to Arielle's classroom, and her glance up at her class to see whether they've followed through, what her action tells students in that moment is at least as important as what she learns from looking. Her message is: I care whether you do what I asked. I will notice whether you do so or not. When we show that it matters to us, it matters more to students. Just by looking, and having students know that we look, we make it more likely that they will follow through; perhaps in part because we've eliminated some gray area, but more likely because we've simply shown that it matters. If you have a strong relationship with students, this will be profoundly influential. If you are still building it, the clarity and competence you show will help earn their trust and respect.

A brief digression here before I return to the second thing Arielle does. Watch the very short video of fourth-grade teacher Katie Kroell (Katie Kroell: Sacrifice). She's an excellent teacher but I've chosen this clip mostly because it is a study of human nature. Notice the young man in the left foreground. He's getting something out of his backpack. It could be anything, honestly: an extra pencil or something he wants to show a classmate. About ten seconds into the video, Katie glances in his direction:

She doesn't do anything else. She doesn't nod her head or wag her finger or frown. It's actually not even clear how she feels about what the student is doing. She merely looks and he decides of his own volition not to get whatever it was out of his backpack. It's his choice, but his choice changes because he knows his teacher is aware of it. I don't need that right now. When people know others are aware of what they are doing, they become more aware of their own choices and they choose differently. This is true almost everywhere in our lives. There's a street near my house where a device on the roadside shows your speed as you drive past. It doesn't take a picture. There are no consequences. It simply tells you how fast you are going. And yet every driver I have ever driven behind slows down.9

That's part of what's happening in Arielle's classroom. When students know that their teacher sees and cares whether they follow a direction, they are suddenly much more likely to follow it.

And this brings me to the second thing Arielle does. She exaggerates her looking ever so slightly so students will be more aware of it. You can see this best in the photos. She lifts her chin in a tiny bit of pantomime. See me looking? This enhances the effect of the preventive benefits of looking, especially for students who are least likely to notice without the extra emphasis. I call this idea Be Seen Looking. Looking is most effective when students are aware of it, so we can help them become more aware of it via subtle nonverbal actions and thus prevent behaviors that would require correction. It's a gift to everybody.

To go back to the photo from Katie's classroom, it's worth asking whether her student would have seen her questioning glance if she hadn't, like Arielle, lifted her chin slightly to make her looking more legible to her student.

Let's call that move Chin Up to make it easy to remember and replicate. And while we're at it, let's call a deliberate scan from one side of the room—to build a habit of looking well—a Swivel. Radar's foundation is the Swivel—the deliberate scan of the classroom that causes you to be sure to see as much as you can. It takes only a second or two. Ideally it would become a habit—you'd give directions and scan without even really thinking to do it.10 It looks like it's a habit for Arielle—her mind is on other things as she scans. But it helps her keep everyone positively engaged and defends against blind spots. And if she sees something small she can redirect it simply and quickly while it's still small. The idea of catching things early while they're tiny so the fix can also be tiny is called “catch it early.” It'll come up later in this chapter. But to catch it early you have to see it early. So you have to look systematically.

You can observe Arielle responding to what her Swivel reveals when she says, “Waiting on two.” As we'll discuss in a few pages this is called an anonymous individual correction. It lets students know she's aware they're a bit behind while preserving their anonymity. In this case they quickly catch up. A potential problem is averted.

You also might notice that Arielle takes a half step back when she scans. It's the equivalent of stepping back when you are taking a photograph to get everyone in the frame. It allows her to see more of the class with less of a Swivel, and it reminds us that where you stand is a major factor in what and how well you see.

Julia Addeo's Swivel is especially good. It's a critical part of her transition about two minutes into her keystone. “Just one piece of feedback. Track up here,” she says to make sure students who were working on their problem set now attend to the discussion. She's at the overhead projector and can't afford to move to a new spot. Perhaps because of this she scans left to right and then back to the left, making it clear without any words that their focus is critical and matters to her. Her students recognize this and seconds later she's teaching to a locked-in room of thirty.

The video Denarius Frazier: Keystone shows Denarius using a Swivel to scan the room several times. The clearest and best example occurs at about 10:20 because his range of motion is relatively narrow. That's because he's taken an even more intentional approach to the question of where to stand. When you stand in the corner of the room you dramatically reduce the field of vision you have to scan and otherwise manage. This makes it simpler to see everything. I call this position Pastore's Perch, after the first teacher I observed using it consistently and intentionally, Patrick Pastore.

You can see math teacher Rodolfo Loureiro standing consistently in Pastore's Perch to see better in Rodolfo Loureiro: Fix Your Mistakes. Each time he gives a direction he walks to the corner of his room and observes from there. This makes it easy for him to see whether students follow through. The movement to the corner also probably makes it clearer to students that he's looking and that it's time for task completion. The combination of these two effects allows Rodolfo to relax and smile warmly. Bonus points to Rodolfo for using different corners so he sees different students with more clarity each time and is in tune with how everyone is doing.

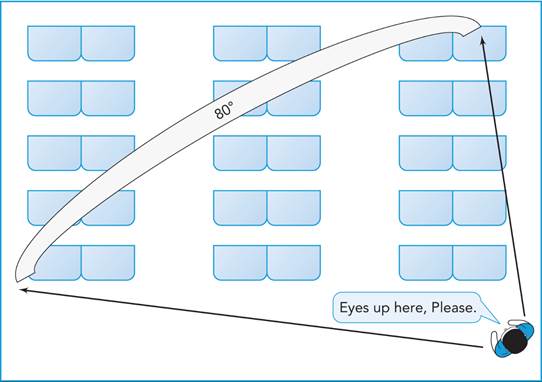

Here's a quick graphic that demonstrates the importance of Pastore's Perch. To see the classroom from the front center you have to scan a field of about 150 degrees. That's a lot to see, but scan carefully and pay special attention to the blind spots in the corners of the visual field. However, if you walk to the corner of your room, you can see the whole room by scanning a visual field of just 80 degrees. It's now simpler to scan.

Be Seen Looking is the yin to Radar's yang. One is seeing well, and the other is contriving ways to subtly remind students that you see them.

In Marisa Ancona: Pens to Paper, you can see Marisa doing this even before class has started. Notice how industriously her students get settled and ready for class. In large part this is because she puts such value on it. She is visibly watching, steadily and calmly with a bit of Chin Up, and making her way from one corner of the room to the other the whole time. What the teacher shows she values, students are more likely to value, and Marisa demonstrates how much she values student focus without saying a word.

Watching the various unspoken pantomimes teachers use to ensure that their students notice them looking, my colleagues on the TLAC team began to give humorous and lighthearted names for the most common among them. They include the Swivel and the Chin Up described earlier in addition to the Sprinkler, an adaptation of the Swivel wherein a teacher starts to Swivel then momentarily doubles back midstream in the direction she'd just scanned as if to say, momentarily, “Oh, I think I just saw something. No. Everything is OK.” It makes the deliberateness of the scan more visible. We called it the Sprinkler because someone in the room noticed that it looked like the 1980s dance move of the same name, and the gag was on. We started to give dance names to all the Be Seen Looking moves. Here are a few more of our favorites:

· The Invisible Column: A teacher moves his head slightly to the side after giving a direction as if he's trying to look around something (an invisible column). You can see Rodolfo Loureiro model his version of this timeless move in the video Montage: Be Seen Looking.

· The Tiptoes: A teacher stands for a moment on her tiptoes while looking out at the room, as if she's just making doubly sure everything is OK in some hard-to-see spot in the room. Kirby Jarrell models an especially impressive version of this in the video Montage: Be Seen Looking.

· The Disco Finger: A teacher traces the track of her gaze in a Swivel with her finger outstretched, pointer style, like one of the killer disco moves you haven't dusted off in a decade or two. It intimates, Let me just check all of these places and makes the Swivel obvious to those who are least likely to notice it. Tamesha McGuire takes this to the next level with her kindergartners in the video Montage: Be Seen Looking. Obviously, her goal here is to make her action especially visible to her little ones. Just a hint of disco finger, low, subtle, perhaps with your finger about at your midriff is probably the trick for your eighth graders.

· The Politician: A teacher acts like an aspiring office holder who walks onstage before a big speech and points in recognition to all of her apparent friends and supporters in the audience—one over here, one over there. As a teacher, you send a similar upbeat message of “I see you all out there” when you gesture briefly to the folks in the audience who are similarly demonstrating that they are with you. The irrepressible Darren Hollingsworth models a useful version of this move in the video Montage: Be Seen Looking and you can see Patrick Pastore doing his version there as well—while standing in Pastore's Perch, no less.

· The QB: A teacher moves like an NFL quarterback (QB) who, crouching behind the center, gazes quickly at the defense. Just because he's low doesn't mean he's not going to scan. Similarly, as champion teachers crouch to confer with a scholar, they flash their eyes briefly across the room, to make sure they see the field. Kathryn Orfuss isn't conferencing with a student in her clip in the video Montage: Be Seen Looking—she's at the overhead projector—but it gives you a good sense for how to look up and glance proactively when you're doing something else.

To summarize, not looking for follow-through after we give a direction can suggest that we don't notice or don't care whether students follow through on our directions, but doing the reverse—showing that we care that they do what we asked—is actually a very strong positive incentive for most students.