5 Steps to a 5: AP English Literature - Estelle M. Rankin, Barbara L. Murphy 2019

Comprehensive review—poetry

Review the knowledge you need to score high

IN THIS CHAPTER

Summary: Overview, including definitions, examples, and practice with poetic forms

Key Ideas

![]() Learn the differences between poetry and prose

Learn the differences between poetry and prose

![]() Understand the structure of poetry

Understand the structure of poetry

![]() Explore various types of poetry

Explore various types of poetry

![]() Practice interpreting selected poems

Practice interpreting selected poems

![]() Compare and contrast given poems

Compare and contrast given poems

Introduction to Poetry

Poetry—the very word inspires fear and trembling, and well it should because it deals with the intensity of human emotion and the experiences of life itself. But there is no reason to fear that which elevates, elucidates, edifies, and inspires. Poetry is a gift of language, like speech and song, and with familiarity comes pleasure and knowledge and comfort.

However, it may still be intimidating to read poetry. After all, we’ve been speaking and reading prose our entire lives. This review assumes that by the time you reach an AP-level literature course, you have some experience and facility with poetry. We provide you with definitions, examples, and practice with interpretation. Hopefully, you will provide the interest, diligence, and critical thinking necessary for a joyful and meaningful experience.

Remember our philosophy of firsts? First, we believe that you should read as much poetry as possible. Early in the year, pick up an anthology of poetry and read, read, read. Open to any page and read for pleasure and interest. Don’t try to “study” the poems; just respond to them on an emotional level. Consider the following:

• Identify subjects that move you or engage you.

• Are there certain themes you respond to? Are there certain poets you like? List them and read more poetry by them.

• Are there certain types or styles of poems you enjoy? What do they seem to have in common?

• Are there images or lines you love? Keep a record of some of your favorites.

Make this a time to develop a personal taste for poetry. Use this random approach to experience a broad range of form and content. You should find that you are more comfortable with poetry simply because you have been discovering it at your own pace.

When you are comfortable and have honestly tried reading it for pleasure, it is time to approach it on a more analytical level.

The Structure of Poetry

What Makes Poetry Different from Prose?

How do you know when you’re working with poetry and not prose? Simple. Just look at it. It’s shorter; it’s condensed; it’s written in a different physical form. The following might help you to visualize the basic differences:

It should not be news to you when we say that poetry sounds different from prose. It is more musical, and it often relies on sound to convey meaning. In addition, it can employ meter, which provides rhythm. Did you know that poetry is from the ancient oral tradition of storytelling and song? Rhyme and meter made it easier for the bards to remember the story line. Try to imagine Homer in a dimly lit hall chanting the story of Odysseus.

As with prose, poetry also has its own jargon. Some of this lingo is specifically related to form and meter. The analysis of a poem’s form and meter is termed scansion.

The Foot

The foot is the basic building block of poetry. It is composed of a pattern of syllables. These patterns create the meter of a poem. Meter is a pattern of beats or accents. We figure out this pattern by counting the stressed and unstressed syllables in a line. Unstressed syllables are indicated with a ˘, and stressed syllables are indicated with a ´.

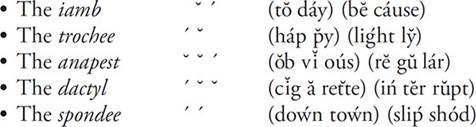

There are five common patterns that are used repeatedly in English poetry. They are:

The Line

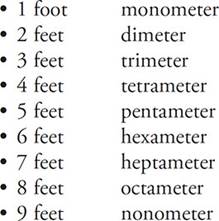

Unlike the prose sentence, which is determined by subject, verb, and punctuation, the poetic line is measured by the number of feet it contains.

Your Turn

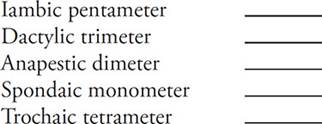

Now answer the following. How many stressed syllables are in a line of:

Note: Answers can be found at the end of the definition of “meter” in the Glossary of terms.

The Stanza

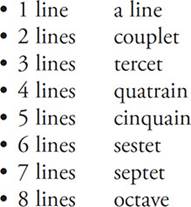

You should now understand that syllables form feet, feet form lines, and lines form stanzas. Stanzas also have names:

Your Turn

What is the total number that results from adding up all of the metric references in the following, make-believe poem?

• The poem is composed of 3 quatrains, 2 couplets, and 1 sestet.

• Each quatrain is written in iambic tetrameter.

• The couplets are dactylic dimeter.

• The sestet is trochaic trimeter.

The total number is ___________________.

Note: You can find the answer at the end of the definition of “rhythm” in the Glossary of terms.

You will never have to be this technical on the AP exam. However, you will probably find a question on meter, and technical terms may be included in the answer choices to the multiple-choice questions. In addition, sometimes in the poetry essay you may find an opportunity to use your knowledge of scansion, or your analysis of the rhyme and meter of the poem, to develop your essay. This can be very effective if it is linked to interpretation.

Rhyme

One of the first processes you should become familiar with concerns the identification of a poem’s rhyme scheme. This is easily accomplished by assigning consecutive letters of the alphabet to each new sound at the end of a line of poetry. Traditionally, rhyme scheme is indicated with italicized, lowercase letters placed to the right of each line of the poem.

• a for the first

• b for the second

• c for the third

• d, e, and so forth

Try this with the opening stanza from “Peace” by George Herbert.

Sweet Peace, where dost thou dwell? I humbly crave,

Let me once know.

I sought thee in a secret cave,

And asked if Peace were there.

A hollow wind did seem to answer, “No,

Go seek elsewhere.”

You may restart the scheme with each new stanza or continue throughout the poem. Remember, the purpose is to identify and establish a pattern and to consider if the pattern helps to develop sound and/or meaning. Here’s what the rhyme scheme looks like for the above selection: a b a c b c.

When you analyze the pattern of the complete poem, you can conclude that there is a very regular structure to this poem which is consistent throughout. Perhaps the content will also reflect a regular development. Certainly the rhyme enhances the sound of the poem and helps it flow. From now on we will refer to rhyme scheme when we encounter a new poem.

The rhymes we have illustrated are called end rhymes and are the most common. Masculine rhyme is the most frequently used end rhyme. It occurs when the last stressed syllable of the rhyming words matches exactly. (“The play’s the thing/Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king.”) However, there are internal rhymes as well. These rhymes occur within the line and add to the music of the poem. An example of this is dreary, in Poe’s “The Raven” (“Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary”). Feminine rhyme involves two consecutive syllables of the rhyming words, with the first syllable stressed. (“The horses were prancing / as the clowns were dancing.”)

Types of Poetry

Because of its personal nature, poetry has evolved into many different forms, each with its own unique purpose and components. What follows is an examination of the most often encountered forms.

Most poetry falls into one of two major categories. Narrative poetry tells a story. Lyric poetry presents a personal impression.

The Ballad

The ballad is one of the earliest poetic forms. It is a narrative that was originally spoken or sung and has often changed over time. It usually:

• Is simple.

• Employs dialogue, repetition, minor characterization.

• Is written in quatrains.

• Has a basic rhyme scheme, primarily a b c b.

• Has a refrain which adds to its songlike quality.

• Is composed of two lines of iambic tetrameter which alternate with two lines of iambic trimeter.

The subject matter of ballads varies considerably. Frequently, ballads deal with the events in the life of a folk hero, like Robin Hood. Sometimes they retell historical events. The supernatural, disasters, good and evil, love and loss are all topics found in traditional ballads.

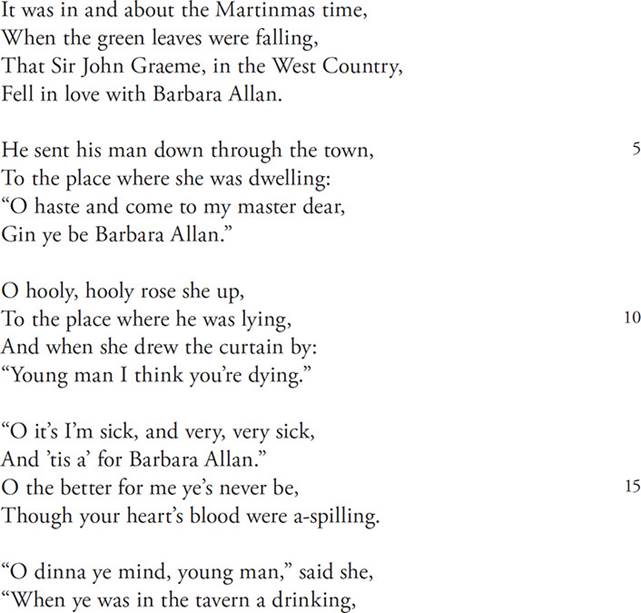

The following is a typical folk ballad. Read this poem out loud. Listen to the music as you read. Get involved in the story. Imagine the scene. Try to capture the dialect or sound of the Scottish burr.

Bonny Barbara Allan

by Anonymous

After you’ve read the ballad, consider the following:

1. Check the rhyme scheme and stanza form. You should notice it is written in quatrains. The rhyme scheme is a little tricky here; it depends on pronunciation and is what is called a forced rhyme. If you soften the “g” sound in the word “falling,” it more closely rhymes with “Allan.” Try this throughout the ballad, recognizing that the spoken word can be altered and stretched to fit the intention of rhyme. This falls under the category of “poetic license.”

2. Follow the plot of the narrative. Poor Barbara Allan, poor Sir John. They are a classic example of thwarted young lovers, a literary pattern as old as Antigone and Haemon or Romeo and Juliet. Love, unrequited love, and dying for love are all universal themes in literature.

3. Observe the use of repetition and how it unifies the poem by sound and structure. “Barbara Allan/Hooly, hooly/Adieu, adieu/Slowly, slowly/Mother, mother.”

4. Notice that dialogue is incorporated into the poem for characterization and plot development.

Don’t be too inflexible when checking rhyme or meter. Remember, never sacrifice meaning for form. You’re smart; you can make intellectual leaps.

Here are some wonderfully wicked and enjoyable ballads to read:

“Sir Patrick Spens”—the tragic end of a loyal sailor

“The Twa Corbies”—the irony of life and nature

“Edward”—a wicked, wicked, bloody tale

“Robin Hood”—still a great, grand adventure

“Lord Randall”—sex, lies, and death in ancient England

“Get Up and Bar the Door”—a humorous battle of the sexes

“La Belle Dame Sans Merci”—John Keats’s fabulous tale of a demon lover

Have you read ballads? Traditional or modern? List them here. Jot down a few details or lines to remind you of important points. If you’re musical, try singing one out loud.

The Lyric

Lyric poetry is highly personal and emotional. It can be as simple as a sensory impression or as elevated as an ode or elegy. Subjective and melodious, it is often reflective in tone.

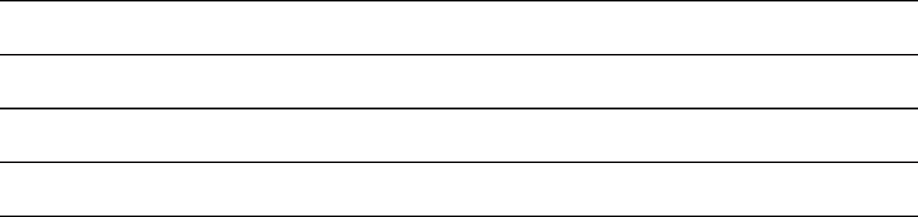

The following is an example of a lyric:

A Red, Red Rose

by Robert Burns

Now answer the following questions:

1. The stanza form is _________________________________________________

2. The rhyme scheme is _________________________________________________

3. The meter of line 6 is _________________________________________________

4. The first stanza depends on similes. Underline them. _________________________________________________

5. Cite assonance in stanza one. _________________________________________________

6. Line 8 is an example of _________________________________________________

7. Highlight alliteration in the poem. _________________________________________________

8. Did you recognize iambic trimeter? How about hyperbole? _________________________________________________

The following are wonderful lyric poems. Read a few.

Edna St. Vincent Millay—“Childhood Is the Kingdom Where Nobody Dies”

Emily Dickinson—“Wild Nights, Wild Nights”

Dylan Thomas—“Fern Hill”

Matthew Arnold—“Dover Beach”

Andrew Marvell—“To His Coy Mistress”

The Ode

The ode is a formal lyric poem that addresses subjects of elevated stature. One of the most beautiful odes in English literature is by Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Ode to the West Wind

As always, read the poem carefully. (Find a private place and read it aloud. You’ll be carried away by the beauty of the sounds and imagery.) Now answer the following questions.

1. Look at the configuration of the poem. It is divided into five sections. What function might each section serve? _______________________________________________

2. Count the lines in each section. How many? ___________ Name the two stanza forms you encountered. _______________________________________________

3. Check the rhyme scheme. Did you come up with a b a b c b c d c d e d e e? The first four tercets are written in a form called terza rima. Notice how this rhyme scheme interweaves the stanzas and creates unity throughout the poem. Did it cross your mind that each section might be a variation on the sonnet form? _______________________________

4. Check the meter. You should notice that it is very irregular. (Freedom of form was a tenet of the Romantic Movement.)

5. Stanza one: Did you catch the apostrophe? The direct address to the wind places us in the poem’s situation and provides the subject of the ode. Highlight the alliteration and trace the similes in line 3. _______________________________________________

6. Stanza two: What are the “pestilence-stricken multitudes”? In addition to leaves, could they be the races of man? _______________________________________________

7. Stanza three: See how the enjambment pulls you into this line. Find the simile. _____________ Alliteration can be seen in “azure,” “sister,” “Spring,” “shall.”

8. Stanza four: What images are presented? _______________ Locate the simile. ________________________________ Find the contrast between life and death. _____________________ Highlight the personification.

9. Identify the essential paradox of the poem and life itself in the couplet.

We are not going to take you through the poem line by line. You may isolate those lines that speak to you. Here are a few of our favorites that are worth a second look:

• Lines 29—31

• Lines 35—42 for assonance

• Lines 53—54

• Lines 55—56

• Lines 57—70

You should be able to follow the development of ideas through the five sections. Were you aware of:

• The land imagery in section 1?

• The air imagery in section 2?

• The water imagery in section 3?

• The comparison of the poet to the wind in section 4?

• The appeal for the spirit of the wind to be the poet’s spirit in section 5?

After you have read the poem, followed the organization, recognized the devices and images, you still have to interpret what you’ve read.

This ode has many possibilities. One interpretation linked it with the French Revolution and Shelley’s understanding of the destructive regeneration associated with it. Another valid reading focuses on Shelley’s loss of faith in the Romantic Movement. He asks for inspiration to breathe life into his work again. Try to propose other interpretations for this “Ode to the West Wind.”

The Elegy

The elegy is a formal lyric poem written in honor of one who has died. Elegiac is the adjective that describes a work lamenting any serious loss.

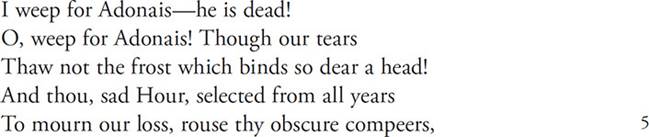

One of the most famous elegies is by Percy Bysshe Shelley. It was written to mourn the loss of John Keats. Here is the first stanza of “Adonais.” It contains all the elements of an elegy.

Adonais*

Read this stanza several times. Try it aloud. Get carried away by the emotion. Respond to the imagery. Listen to the sounds; let the meter and rhyme guide you through. Consider the following:

1. Adonais, Shelley’s name for Keats, is derived from Adonis. This is a mythological allusion to associate Keats with love and beauty. (The meter will tell you how to pronounce Adonais.)

2. Check the rhyme scheme. Did you come up with a b a b b c b c c? See how the last two lines are rhymed to set this idea apart.

3. Line 1 contains a major caesura in the form of a dash. This forces the reader to pause and consider the depth of emotion and the finality of the event. The words that follow are also set off by the caesura and emphasized by the exclamation point. Notice that the meter is not interrupted by the caesura. (![]() is perfect iambic pentameter.) This line is a complete thought which is concluded by punctuation and is an example of an end-stopped line.

is perfect iambic pentameter.) This line is a complete thought which is concluded by punctuation and is an example of an end-stopped line.

4. Line 2 utilizes repetition to intensify the sense of loss. Here the caesura is an exclamation point. Notice that the last three words of the line fulfill the meter of iambic pentameter but do not express a complete thought as did line 1. The thought continues into line 3. This is an example of enjambment.

5. Lines 2 and 3 contain alliteration (“Though,” “tears,” “Thaw,” “the”) and consonance (“not,” “frost,” continuing into line 4 with “thou”).

6. Line 3 contains imagery and metaphor. What does the frost represent?

7. Line 4 contains an apostrophe, which is a direct address to the sad Hour, which is personified. To what event does the “sad Hour” refer?

8. Lines 4, 5, and 6 incorporate assonance. The vowel sounds provide a painful tone through “ow” sounds (“thou,” “Hour,” “our,” “rouse,” “sorrow”).

9. Notice how the enjambment in lines 7—9 speeds the stanza to the final thought. This helps the pacing of the poem.

10. Reread the poem. Choose images and lines you respond to.

Have you read any elegies? List them here. Jot down the poet, title, and any images and lines you like. Add your own thoughts about the poem.

Following is a list of some of the most beautiful elegies in the English language. Make it a point to read several. You won’t be sorry.

“Elegy for Jane” by Theodore Roethke—a teacher’s lament for his student.

“Elegy in a Country Church Yard” by Thomas Gray—a reflective look at what might have been.

“When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomed” and “O Captain, My Captain” by Walt Whitman—tributes to Abraham Lincoln.

“In Memory of W. B. Yeats” by W. H. Auden—a poet’s homage to a great writer.

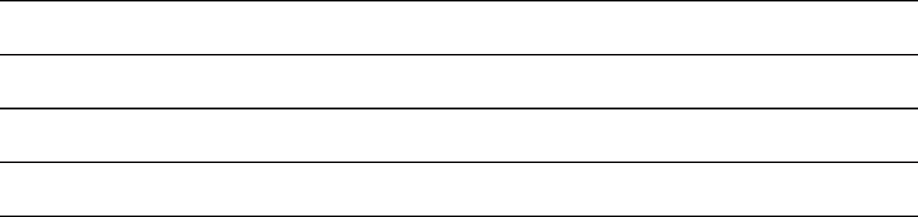

The Dramatic Monologue

The dramatic monologue relates an episode in a speaker’s life through a conversational format that reveals the character of the speaker.

Robert Browning is the acknowledged master of the dramatic monologue. The following is an example of both the dramatic monologue and Browning’s skill as a poet.

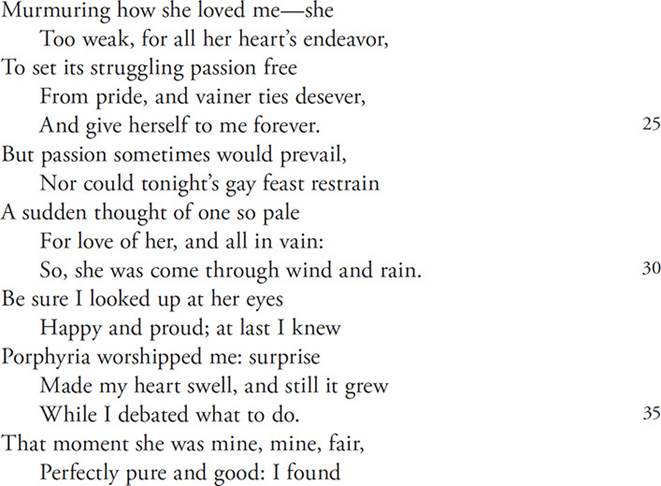

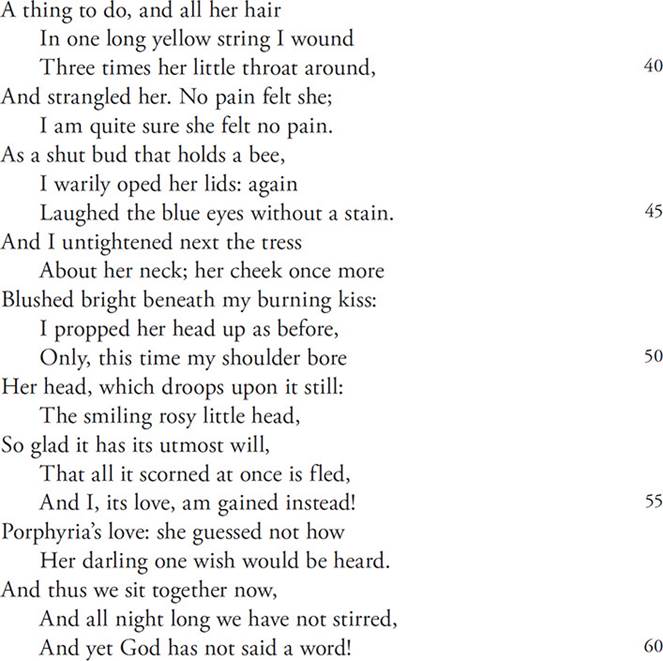

Porphyria’s Lover

Read the poem aloud, or have someone read it to you. Try for a conversational tone.

1. Concentrate on following the storyline. (Were you surprised by the concluding events?) _______________________________________________________________

2. Once you know the “story,” look closely at the poem for all the clues concerning character and episode.

3. Automatically check for the relationship between form and content. Quickly scan for rhyme scheme and meter. You should notice a definite presence of rhyme in an unusual form a b a b b c d c d d e f e f f, etc. You should be able to recognize that the meter is iambic tetrameter. Rather than scan the entire poem, try lines throughout to see if a pattern exists.

4. Lines 1—5: What does the setting indicate or foreshadow?

Lines 6—9: What diction and imagery is associated with Porphyria?

Lines 10—12: Why are we told her gloves were soiled?

Lines 20—25: Try to understand what the narrator is telling you here.

This reveals what is important to him. ___________________________________

Lines 30—37: Have you found the turning point? ______________________

Remember, literary analysis is like unraveling a mystery. Find motivational and psychological reasons for the narrator’s behavior. _________________________

Line 41: Notice how the caesura emphasizes the finality of the event. You are forced to confront the murder directly because of the starkness of the syntax. This is followed by the narrator’s justification.

Line 43: Did you catch the simile? It’s a little tricky to spot when “as” is the first word.

Line 55: What character trait is revealed by the narrator? _________________________________

Lines 59—60: Notice how the rhyming couplet accentuates the final thought and sets it off from the previous lines. Interpret the last line. Did you see that the last two lines are end-stopped, whereas the majority of the poem utilizes enjambment to create a conversational tone? _______________________________

5. Did you enjoy this poem? Did you feel as if you were being spoken to directly? ______

The AP often uses dramatic monologues because they can be very rich in narrative detail and characterization. This is a form you should become familiar with by reading several from different times and authors. Try one of these: Robert Browning —“My Last Duchess,” “The Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister,” “Andrea Del Sarto”; Alfred Lord Tennyson —“Ulysses.”

How many dramatic monologues have you read? List them here and add details and lines that were of interest and /or importance to you.

The Sonnet

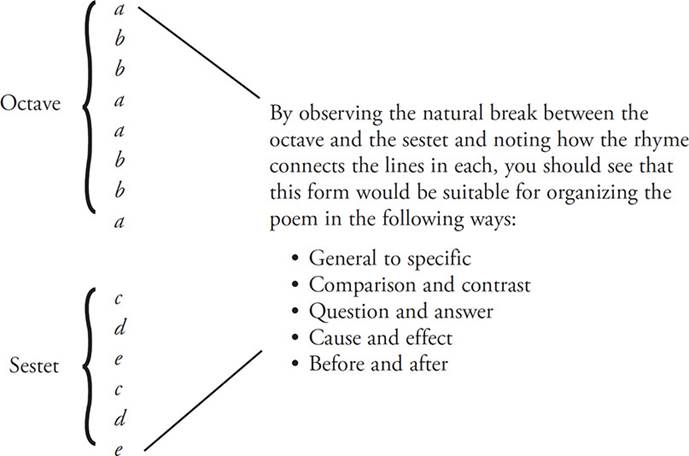

The sonnet is the most popular fixed form in poetry. It is usually written in iambic pentameter and is always made up of 14 lines. There are two basic sonnet forms: the Italian or Petrarchan sonnet, named after Petrarch, the poet who created it, and the English or Shakespearean sonnet, named after the poet who perfected it. Each adheres to a strict rhyme scheme and stanza form.

The subject matter of sonnets varies greatly, from expressions of love to philosophical considerations, religious declarations, or political criticisms. The sonnet is highly polished, and the strictness of its form complements the complexity of its subject matter. As you know by now, we like to explore the relationship between form and function. The sonnet effectively integrates these two concepts.

Let’s compare the two forms more closely. The Italian sonnet is divided into an octave and a sestet. The rhyme scheme is:

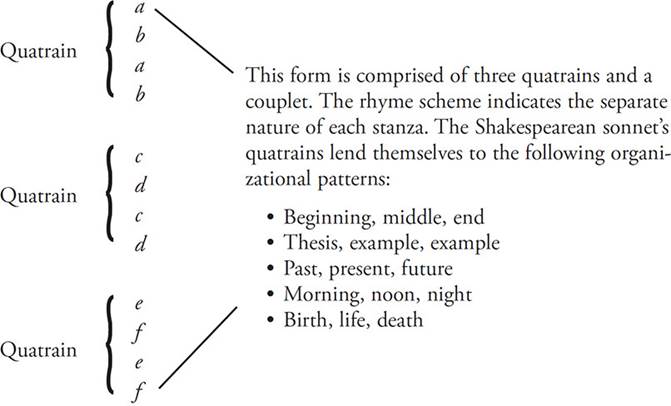

The Shakespearean sonnet has a different rhyme scheme and stanza form:

The couplet then serves to present:

Modern sonnets often vary rhyme and stanza form, but they will always have 14 lines.

For more practice with the sonnet, see Poems for Comparison and Contrast in this chapter. We recommend you read sonnets written by Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth, e e cummings, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Keats.

The Villanelle

The villanelle is a fixed form in poetry. It has six stanzas: five tercets, and a final quatrain. It utilizes two refrains: The first and last lines of the first stanza alternate as the last line of the next four stanzas and then form a final couplet in the quatrain.

As an example, read: “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” by Dylan Thomas. Other villanelles that are worth a close reading include “The Art of Losing” by Elizabeth Bishop and “The Waking” by Theodore Roethke.

Interpretation of Poetry

Interpretation is not license for you to say just anything. Your comments/analysis/interpretation must be based on the given text.

How Do I Begin to Interpret Poetry?

To thoroughly understand a poem, you should be able to view it and read it from three different angles or viewpoints.

The first level is the literal reading of the poem. This is the discovery of what the poem is actually saying. For this, you only use the text:

• Vocabulary

• Structure

• Imagery

• Poetic devices

The second level builds on the first and draws conclusions from the connotation of the form and content and the interpretation of symbols. The third level refers to your own reading and interpretation of the poem. Here, you apply the processes of levels one and two, and you bring your own context or frame of reference to the poem. Your only restriction is that your interpretation is grounded in, and can be supported by, the text of the poem itself.

To illustrate this approach, let’s analyze a very simple poem.

Where ships of purple gently toss

On seas of daffodil,

Fantastic sailors mingle

And then, the wharf is still.

1. Read it.

2. Respond. (You like it; you hate it. It leaves you cold. Whatever.)

3. Check rhyme and meter. We can see there is some rhyme, and the meter is iambic and predominantly trimeter. The first and third lines are irregular. (If this does not prove to be critical to your interpretation of the poem, move on.)

4. Check the vocabulary and syntax. Are there any words you are not familiar with?

5. Look for poetic devices and imagery.

6. Highlight, circle, connect key images and words.

7. Begin to draw inferences from the adjectives, phrases, verbs.

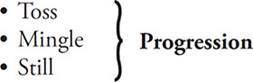

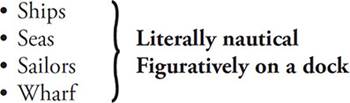

As an example, we have provided the following notes:

Movement

Images

Syntax

• Ships of purple = purple ships (Where or when do you see purple ships?)

• Seas of daffodil = daffodil seas (When would seas be yellow?)

• Fantastic sailors = sailors of fantasy = clouds moving, birds flying (What might they be?)

• Wharf is still = place is quiet = ?

Put your observations together and formulate your interpretation. Write it below.

Some students have said that they saw a field of flowers, bees and butterflies, a coronation, a celebration, and/or a royal event. These are all valid interpretations. Remember, this is only a simple exercise to acquaint you with the approaches you can use to analyze complex poetry. By the way, Emily Dickinson was writing about a sunset over Boston harbor.

Poetry for Analysis

This section will walk you through the analysis of several poems, presenting the poetry and a series of directed questions for you to consider. For maximum benefit, work with a highlighter and refer often to the poem. Always read the entire poem before you begin the analysis.

The Snake

by D. H. Lawrence

1. Since there is no regular rhyme scheme or length of lines or stanza form, we may conclude that this is free verse. ___________ Yes ___________ No

2. After reading the poem, you should be able to determine the situation, which is ____________________________________________, and the speaker, who is ________________________________________________________________.

3. The first stanza establishes the conflict, which is _______________________________________________________________.

4. Find evidence of the developing conflict in lines 4—6. ____________________________

5. Find examples of alliteration and assonance in lines 7—13. Notice how the sounds are appropriate for a snake rather than just random sounds.

6. Read line 12 aloud. Hear how slowly and “long” the sounds are, like the body of the snake itself.

7. Circle or highlight the imagery in lines 16—24. ____________________________ Notice how the scene is intensifying.

8. Restate the speaker’s position in lines 25—28. ____________________________

9. In lines 31—38, identify the conflict and the thematic ideas of the poem. Highlight them.

10. Identify the opposition facing the speaker in lines 36—39. State it. ___________________________________________________________________________

11. In lines 46—54, highlight the similes presented. Explore the nature of a snake and the connotation associated with one. _________________________________________

12. Interpret the setting as presented in lines 55—62. ________________________________

13. The poem breaks at line 63. Highlight the change in the speaker at this point. Who is to blame for this action? __________________________________________________

14. In line 75 there is a reference or allusion to the “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” by Coleridge, which is a poem in which a man learns remorse and the meaning of life as the result of a cruel, spontaneous act. Is this a suitable comparison for this poem’s circumstances? Why? _________________________________________________________

15. Identify the similes and metaphor in lines 66—71. _____________________________

16. Elaborate on the final confession of the speaker. May we conclude that the poem is a modern dramatic monologue? ___________________________________________

After you have considered these ideas, expand your own observations. Might the entire poem be a metaphor? Can it be symbolic of other pettinesses? Can you interpret this poem socially, religiously, politically, psychologically, sexually?

The following poem is particularly suitable for the interpretation of symbolism. Apply what you have learned and reviewed and respond to this sample.

The Sick Rose

by William Blake

O Rose, Thou Art Sick!

The Invisible Worm

That flies in the night

In the howling Storm,

Has found out thy bed

Of Crimson joy,

And his dark secret love

Does thy life destroy.

Try your hand at interpreting this poem:

1. Literally

2. Sexually

3. Philosophically

4. Religiously

5. Politically

Apply the following thematic concepts to the poem:

1. Passion

2. Deceit

3. Betrayal

4. Corruption

5. Disease

6. Madness

Interesting, isn’t it, how much can be found or felt in a few lines. Read other poems by Blake, such as “Songs of Innocence” and “Songs of Experience.”

Poems for Comparison and Contrast

Sometimes the AP exam requires you to compare and contrast two poems or prose selections in the essay section. Do not panic. The selections will usually be short and the points of comparison or contrast plentiful and accessible. This type of question can be interesting and provide you with a chance to really explore ideas.

Following are two poems suitable for this kind of analysis. Read each poem carefully. Take a minute to look at them and allow a few ideas to take shape in your mind. Then plan your approach logically. Remember, form and content are your guidelines.

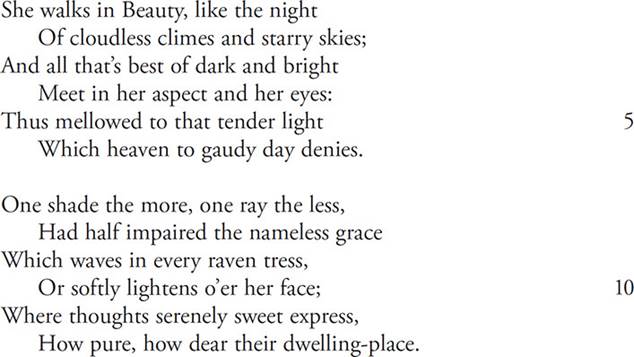

She Walks in Beauty

by Lord Byron

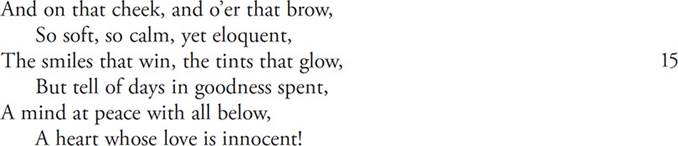

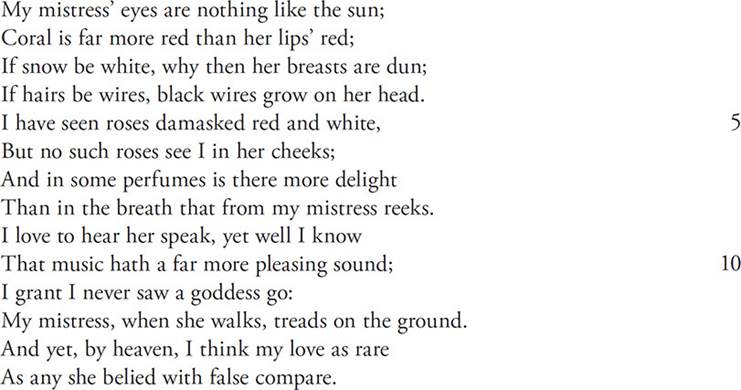

Sonnet 130

by William Shakespeare

It is essential that you read each poem again, marking, highlighting, connecting, etc. those points you will develop. List or chart your findings before you begin to write your essay.

Common Elements

• Both have the same topic—to a lover

• Both use similes: “She Walks”—“like the night”; “Sonnet 130”—“nothing like the sun”

• Both rely on nature imagery: “She Walks”—“starry skies”; “Sonnet 130”—“Coral, roses”

• Both deal with light or dark

• Both include references to lover’s hair: “She Walks”—“raven tress”; “Sonnet 130”—“black wires”

• Both appeal to the senses: “She Walks”—“raven tress”; “Sonnet 130”—perfume, roses, music, garlic stink

• Both use alliteration: “She Walks”—“cloudless climes”; “Sonnet 130”—“goddess go”

Differences

• Form: “She Walks” lyric, has sestets; “Sonnet 130,” 12 + 2 (3 quatrains and couplet)

• Kind of love: “She Walks” serious and adoring; “Sonnet 130”—critical and humorous

• Diction: “She Walks”—positive; “Sonnet 130”—negative

• Ending: “She Walks”—adoring; “Sonnet 130”—realistic

• Tone: “She Walks”—idyllic; “Sonnet 130”—realistic

“Practice. Practice. Practice.”

—Martha W. AP teacher

To recap: If you are given two selections, consider the following:

• What is the form or structure of the poems?

• What is the situation or subject of each?

• How are the poetic devices used?

• What imagery is developed?

• What thematic statements are made?

• What is the tone of each poem?

• What is the organization or progression of each poem?

• What attitudes are revealed?

• What symbols are developed?

Rapid Review

• Poetry has its own form.

• The foot, line, and stanza are the building blocks of poetry.

• Meter and rhyme are part of the sound of poetry.

• There are many types of rhyme forms.

• There are many types of poetic feet. They may be iambic, trochaic, anapestic, dactylic, or spondaic.

• There are several stanza forms.

• Narrative poetry tells stories.

• Ballads are simple narratives.

• Lyric poetry is subjective and emotional.

• Odes are formal lyrics that honor something or someone.

• Elegies are lyrics that mourn a loss.

• Dramatic monologues converse with the reader as they reveal events.

• The sonnet is a 14-line form of poetry.

• The villanelle is a fixed form that depends on refrains.

• Levels of interpretation depend on the literal and figurative meaning of poems.

• Symbols provide for many levels of interpretation.

• When comparing and contrasting poems, remember to consider speaker, subject, situation, devices, tone, and theme.