5 Steps to a 5: AP English Literature - Estelle M. Rankin, Barbara L. Murphy 2019

Section i of the exam: The multiple-choice questions

Develop strategies for success

IN THIS CHAPTER

Summary: Become comfortable with the multiple-choice section of the exam. If you know what to expect, you can prepare.

Key Ideas

![]() Review the types of multiple-choice questions asked on the exam

Review the types of multiple-choice questions asked on the exam

![]() Learn strategies for approaching the multiple-choice questions

Learn strategies for approaching the multiple-choice questions

![]() Prepare yourself for the multiple-choice section of the exam

Prepare yourself for the multiple-choice section of the exam

![]() Take the multiple-choice section of the exam

Take the multiple-choice section of the exam

![]() Score yourself by checking the answer key and explanations for the multiple-choice section of the Diagnostic/Master exam

Score yourself by checking the answer key and explanations for the multiple-choice section of the Diagnostic/Master exam

Introduction to the Multiple-Choice Section of the Exam

Multiple choice? Multiple guess? Multiple anxiety? The day after the exam, students often bemoan the difficulties and uncertainties of Section I of the AP Literature exam.

“It’s unfair.”

“It’s crazy.”

“Was that in English?”

“Did you get four Ds in a row for the second poem?”

“I just closed my eyes and pointed.”

Is it really possible to avoid these and other exam woes? We hope that by following along with us in this chapter, you will begin to feel a bit more familiar with the world of multiple-choice questions and, thus, become a little more comfortable with the multiple-choice section of the exam.

What Is It About the Multiple-Choice Questions That Causes Such Anxiety?

Basically, a multiple-choice literature question is a flawed method of gauging understanding because, by its very nature, it forces you to play a cat-and-mouse game with the test maker, who demands that you concentrate on items that are incorrect before you can choose what is correct. We know, however, that complex literature has a richness that allows for ambiguity. When you are taking the exam, you are expected to match someone else’s take on a work with the answers you choose. This is what often causes the student to feel that the multiple-choice section is unfair. And maybe, to a degree, it is. However, the test is designed to allow you to shine, not to be humiliated. To that end, you will not find “cutesy” questions, and the test writers will not play games with you. What they will do is present several valid options as a response to a challenging and appropriate question. These questions are designed to separate the perceptive and thoughtful reader from the superficial and impulsive one.

This said, it’s wise to develop a strategy for success. Practice is the key to this success. You’ve been confronted with all types of multiple-choice questions during your career as a student. The test-taking skills you have learned in your social studies, math, and science classes may also apply to the AP Literature exam.

What Should I Expect in Section I?

For this first section of the AP Literature exam, you are allotted 1 hour to answer approximately 55 objective questions on four or five prose and poetry selections. The prose passage will comprise works of fiction or drama. You can expect the poems to be complete and from different time periods and of different styles and forms. In other words, you will not find two Shakespearean sonnets on the same exam.

These are not easy readings. They are representative of the college-level work you have been doing throughout the year. You will be expected to

• Follow sophisticated syntax

• Respond to diction

• Be comfortable with upper-level vocabulary

• Be familiar with literary terminology

• Make inferences

• Be sensitive to irony and tone

• Recognize components of style

The good news is that the selection is self-contained. This means that if it is about the Irish Potato Famine, you will not be at a disadvantage if you know nothing about it prior to the exam. Frequently there will be biblical references in a selection. This is especially true of works from an earlier time period. You are expected to be aware of basic allusions to biblical and mythological works often found in literature, but the passage will never require you to have any specific religious background.

Do not let the subject matter of a passage throw you. Strong analytical skills will work on any passage.

How Should I Begin to Work with Section I?

Take no more than a minute and thumb through the exam, looking for the following:

• The length of the selections

• The time periods or writing styles, if you can recognize them

• The number of questions asked

• A quick idea of the type of questions

This brief skimming of the test will put your mind into gear because you will be aware of what is expected of you.

How Should I Proceed Through This Section of the Exam?

Timing is important. Always maintain an awareness of the time. Wear a watch. (Some students like to put it directly in front of them on the desk.) Remember, this will not be your first encounter with the multiple-choice section of the test. You’ve probably been practicing timed exams in class; in addition, this book provides you with three timed experiences. We’re sure you will notice improvements as you progress through the timed practice activities.

“Creating my own multiple-choice questions was a terrific help to me when it came to doing close readings and correctly answering multiple-choice questions on the exam.”

—Bill N. AP student

Depending on the given selections, you may take less or more time on a particular passage, but you must know when to move on. The test does not become more difficult as it progresses. So, you will want to give yourself adequate opportunity to answer each set of questions.

Work at a pace of about one question per minute. Every question is worth the same number of points, so don’t get bogged down on those that involve multiple tasks. Don’t panic if a question is beyond you. Remember, it will probably be beyond a great number of other students as well. There has to be a bar that determines the 5’s and 4’s for this exam. Just do your best.

Reading the text carefully is a must. Begin at the beginning and work your way through. Do not waste time reading questions before you read the selection.

Most people read just with their eyes. We want you to slow down and read with your senses of sight, sound, and touch.

• Underline, circle, bracket, or highlight the text.

• Read closely, paying attention to punctuation and rhythms of the lines or sentences.

• Read as if you were reading the passage aloud to an audience, emphasizing meaning and intent.

• As corny as it may seem, hear those words in your head.

• This technique may seem childish, but it works. Using your finger as a pointer, under-score the line as you are reading it aloud in your head. This forces you to slow down and to really notice the text. This will be helpful when you have to refer to the passage.

• Use all the information given to you about the passage, such as title, author, date of publication, and footnotes.

• Be aware of foreshadowing.

• Be aware of thematic lines and be sensitive to details that will obviously be material for multiple-choice questions.

• When reading poetry, pay particular attention to enjambment and end-stopped lines because they carry meaning.

• With poetry, it’s often helpful to paraphrase a stanza, especially if the order of the lines has been inverted.

You can practice these techniques any time. Take any work and read it aloud. Time yourself. A good rate is about 1½ minutes per page.

Types of Multiple-Choice Questions

Multiple-choice questions are not written randomly. There are certain formats you will encounter. The answers to the following questions should clarify some of the patterns.

Is the Structure the Same for All of the Multiple-Choice Questions?

No. Here are several basic patterns that the AP test makers often employ:

1. The straightforward question, such as:

• The poem is an example of a

C. lyric

• The word “smooth” refers to

B. his skin

2. The question that refers you to specific lines and asks you to draw a conclusion or to interpret.

• Lines 52—57 serve to

A. reinforce the author’s thesis

3. The “all . . . except” question requires extra time because it demands that you consider every possibility.

• The AP Literature exam is all of the following except:

A. It is given in May of each year.

B. It is open to high school seniors.

C It is published in The New York Times.

D. It is used as a qualifier for college credit.

E. It is a 3-hour test.

4. The question that asks you to make an inference or to abstract a concept that is not directly stated in the passage.

• In the poem “My Last Duchess,” the reader can infer that the speaker is

E. arrogant

5. Here is the killer question. It uses Roman numerals, no less! The question employing Roman numerals is problematic and time-consuming. You can be certain that each exam will have several of these questions.

• In the poem, “night” refers to

I. the death of the maiden

II. a pun on Sir Lancelot’s title

III. the end of the affair

A. I only

B. I and II

C. I and III

D. II and III

E. I, II, and III

This is the type of question to skip if it causes you problems and/or you are short on time.

What Kinds of Questions Should I Expect on the Exam?

The multiple-choice questions center around form and content. The test makers want to assess your understanding of the meaning of the selection as well as your ability to draw inferences and perceive implications based on it. They also want to know whether you understand how a writer develops his or her ideas.

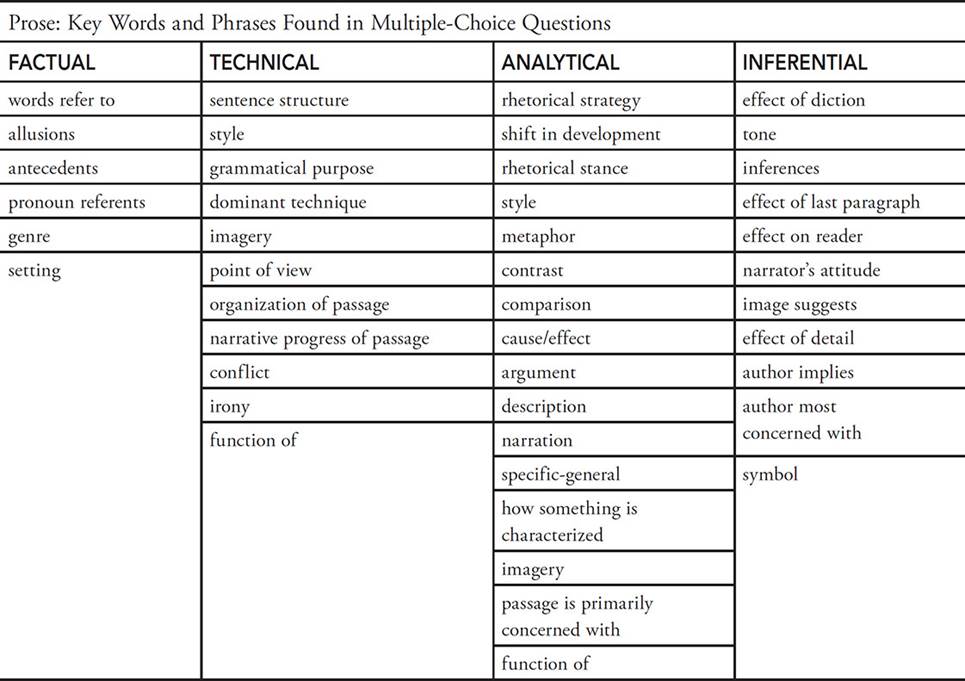

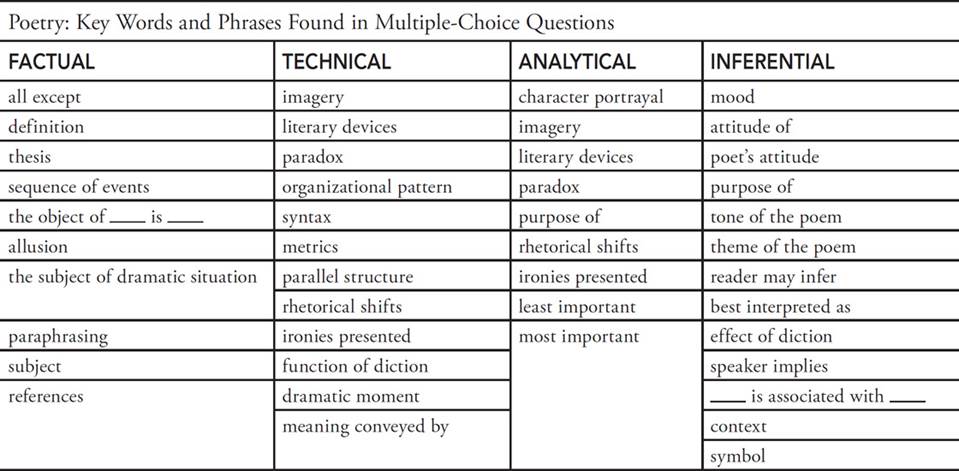

The questions, therefore, will be factual, technical, analytical, and inferential. The two tables that follow illustrate the types of key words and phrases in these four categories that you can expect to find in questions for both the prose and the poetry selections.

Note: Do not memorize these tables. Also, do not panic if a word or phrase is unfamiliar to you. You may or may not encounter any or all of these words or phrases on any given exam. You can, however, count on meeting up with many of these in the practice exams in this book.

A word about jargon. Jargon refers to words that are unique to a specific subject. A common language is important for communication, and there must be agreement on the basic meanings of terms. Even though it is important to know the universal language of a subject, it is also important that you not limit the scope of your thinking to a brief definition. All the terms used in the tables are interwoven in literature. They are categorized only for easy reference. They also work in many other contexts. In other words, think beyond the box.

Scoring the Multiple-Choice Section

How Does the Scoring of the Multiple-Choice Section Work?

The College Board has implemented a new scoring process for the multiple-choice section of the AP English Literature and Composition exam. No longer are points deducted for incorrect responses, so there is no longer a penalty for guessing incorrectly. Therefore, it is to your advantage to answer ALL of the multiple-choice questions. Your chances of guessing the correct answer improve if you skillfully apply the process of elimination to narrow the choices.

Multiple-choice scores are based solely on the number of questions answered correctly. If you answered 36 questions correctly, then your raw score is 36. This raw score, which is 45 percent of the total, is combined with that of the essay section to make up a composite score. This is then manipulated to form a scale on which the final AP grade is based.

Strategies for Answering the Multiple-Choice Questions

You’ve been answering multiple-choice questions most of your academic life, and you’ve probably figured out ways to deal with them. However, there may be some points you have not considered that will be helpful for this particular exam.

General Guidelines

• Work in order. This is a good approach for several reasons:

• It’s clear.

• You will not lose your place on the scan sheet.

• There may be a logic to working sequentially that will help you answer previous questions. But, this is your call. If you are more comfortable moving around the exam, do so.

• Write on the exam booklet. Mark it up. Make it yours. Interact with the test.

• Do not spend too much time on any one question.

• Focus on your strengths. If you are more comfortable working with poetry, answer the poetry questions first.

• Don’t be misled by the length or appearance of a selection. There is no correlation between length or appearance and the difficulty of the questions.

• Don’t fight the question or the passage. You may know other information about the subject of the text or a question. It’s irrelevant. Work within the given context.

• Consider all the choices in a given question. This will keep you from jumping to a false conclusion. It helps you to slow down and to really look at each possibility. You may find that your first choice is not the best or most appropriate one.

• Maintain an open mind as you answer subsequent questions in a series. Sometimes the answer to a later question will contradict your answer to a previous one. Reconsider both answers. Also, the phrasing of a question may point to an answer in a previous question.

• Remember that all parts of an answer must be correct.

• When in doubt, go to the text.

Specific Techniques

• Process of elimination: This is your primary tool, except for direct knowledge of the answer.

1. Read the five choices.

2. If no choice immediately strikes you as correct, you can

• Eliminate those choices that are obviously wrong

• Eliminate those choices that are too narrow or too broad

• Eliminate illogical choices

• Eliminate answers that are synonymous

• Eliminate answers that cancel each other out

3. If two answers are close, do one or the other of the following:

• Find the one that is general enough to cover all aspects of the question

• Find the one that is limited enough to be the detail the question is looking for

• Substitution/fill in the blank

1. Rephrase the question, leaving a blank where the answer should go.

2. Use each of the choices to fill in the blank until you find the one that is the best fit.

• Using context

1. Consider the context when the question directs you to specific lines, words, or phrases.

2. Locate the given word, phrase, sentence, or poetic line and read the sentence or line before and after the section of the text to which the question refers. Often this provides the information or clues you need to make your choice.

• Anticipation: As you read the passage for the first time, mark any details and ideas that you would ask a question about. You may be able to anticipate the test makers this way.

• Intuition or the educated guess: You have a wealth of skills and knowledge in your literary subconscious. A question or a choice may trigger a “remembrance of things past.” This can be the basis for your educated guess. Have the confidence to use the educated guess as a valid technique. Trust your own resources.

Survival Plan

If time is running out and you haven’t finished the fourth selection:

1. Scan the remaining questions and look for:

• The shortest questions

• The questions that direct you to a specific line.

2. Look for specific detail/definition questions.

3. Look for self-contained questions. For example: “The sea slid silently from the shore” is an example of C. alliteration. You do not have to go to the passage to answer this question.

If I Don’t Know an Answer, Should I Guess?

You can’t be seriously hurt by making educated guesses based on a careful reading of the selection. Be smart. Understand that you need to come to this exam well prepared. You must have a foundation of knowledge and skills. You cannot guess through the entire exam and expect to do well.

This is not Lotto. This book is not about how to “beat the exam.” We want to maximize the skills you already have. There is an inherent integrity in this exam and your participation in it. With this in mind, when there is no other direction open to you, it is perfectly fine to make an educated guess.

Is There Anything Special I Should Know About Preparing for the Prose Multiple-Choice Questions?

After you have finished with the Diagnostic/Master exam, you will be familiar with the format and types of questions asked on the AP Lit exam. However, just practicing answering multiple-choice questions on specific works will not give you a complete understanding of this questioning process. We suggest the following to help you hone your multiple-choice answering skills with prose multiple-choice questions:

• Choose a challenging passage from a full-length prose work.

• Read the selection a couple of times and create several multiple-choice questions about specific sections of the selection.

• Make certain the section is self-contained and complex.

• Choose a dialogue, monologue, introductory setting, set description, stage directions, philosophical passage, significant event, or moment of conflict.

• Create a variety of question types based on the previous chart.

• Refer to the prose table given earlier in this chapter for suggested language and type.

• Administer your mini-quiz to a classmate, study group, or class.

• Evaluate your results.

• Repeat this process through several different full-length works during your preparation for the exam. The works can certainly come from those you are studying in class.

“One of my biggest challenges in preparing for the exam was to learn not to jump to conclusions when I was doing the multiple-choice questions.”

—Samantha S. AP student

Here’s what should happen as a result of your using this process:

• Your expectation level for the selections in the actual test will be more realistic.

• You will become familiar with the language of multiple-choice questions.

• Your understanding of the process of choosing answers will be heightened.

• Questions you write that you find less than satisfactory will trigger your analytical skills as you attempt to figure out “what went wrong.”

• Terminology will become more accurate.

• Bonus: If you continue to do this work throughout your preparation for the AP exam, you will have created a mental storehouse of literary information. So when you are presented with a prose or free-response essay in Section II, you will have an extra resource at your disposal.

Your Turn

To Do:

1. Circle/highlight/underline the words and/or phrases that appear to be important for the meaning of the excerpt.

2. Carefully consider each of the given sample questions.

3. Construct your own question that is an example of the specific type.

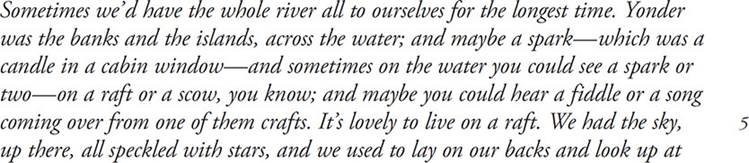

from Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn

Title: Huckleberry Finn

Author: Mark Twain

Type of passage: Narrative description

Sample Factual Question: In lines 10—11, “I’ve seen a frog lay most as many” refers to

Sample Technical Question: A primary function of the sentence “It’s lovely to live on a raft” is

Sample Analytical Question: The primary purpose of using dialect is most likely to

Sample Inferential Question: The tone of the passage can best be described as

Is There Anything Special I Should Do to Prepare for the Poetry Questions?

The points made about prose hold true for the poetry multiple-choice questions as well. But there are a few specific pointers that may prove helpful:

• Choose thoughtful and interesting poems of some length. (See our suggested reading list.)

• Read the poems several times. Practice reading the poems aloud.

• The greatest benefit will be that as you read any poem, you will automatically begin to respond to areas of the poem that would lend themselves to a multiple-choice question.

• Here is a list of representative poets you may want to read.

• Shakespeare

• John Donne

• Philip Larkin

• Emily Dickinson

• Sylvia Plath

• Dylan Thomas

• May Swenson

• Theodore Roethke

• Sharon Olds

• Billy Collins

• Pablo Neruda

• Richard Wilbur

• Adrienne Rich

• Edmund Spenser

• W. H. Auden

• W. B. Yeats

• Gwendolyn Brooks

• Elizabeth Bishop

• Langston Hughes

• Galway Kinnell

• Marianne Moore

• May Sarton

You might want to utilize this process throughout the year with major works studied in and out of class and keep track of your progress. See the Bibliography of this book.

Your Turn

To Do:

4. Circle/highlight/underline the words and/or phrases that appear to be important for the meaning of the poem.

5. Carefully consider each of the given sample questions.

6. Construct your own question that is an example of the specific type.

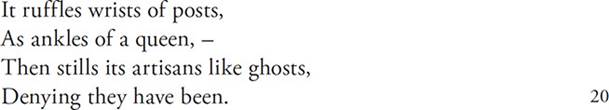

It Sifts from Leaden Sieves

By Emily Dickinson

Title: “It Sifts from Leaden Sieves”

Poet: Emily Dickinson

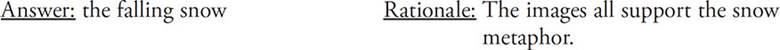

Sample Factual Question: The subject of the poem’s dramatic situation is

Sample Technical Question: The primary literary device used in the poem is

![]()

Sample Analytical Question: Paradox is most readily seen in

Sample Inferential Question: Based on the poem, the reader could infer that

![]()

The Time Is at Hand

It is now time to try the Diagnostic/Master exam, Section I. Do this section in one sitting. Time yourself ! Be honest with yourself when you score your answers.

Note: If the 1 hour passes before you finish all the questions, stop where you are and score what you have done up to this point. Afterwards, answer the remaining questions, but do not count the answers as part of your score.

When you have completed all the multiple-choice questions in this Diagnostic/Master exam, carefully read the explanations of the answers. Spend time here and assess which types of questions give you trouble. Use this book to learn from your mistakes.

ANSWER SHEET FOR DIAGNOSTIC MULTIPLE-CHOICE QUESTIONS

1. _______

2. _______

3. _______

4. _______

5. _______

6. _______

7. _______

8. _______

9. _______

10. _______

11. _______

12. _______

13. _______

14. _______

15. _______

16. _______

17. _______

18. _______

19. _______

20. _______

21. _______

22. _______

23. _______

24. _______

25. _______

26. _______

27. _______

28. _______

29. _______

30. _______

31. _______

32. _______

33. _______

34. _______

35. _______

36. _______

37. _______

38. _______

39. _______

40. _______

41. _______

42. _______

43. _______

44. _______

45. _______

46. _______

47. _______

I _____ did _____ did not finish all the questions in the allotted 1 hour.

I had _____ correct answers. I had _____ incorrect answers. I left _____ questions blank.

I have carefully reviewed the explanations of the answers, and I think I need to work on the following types of questions:

THE MULTIPLE-CHOICE SECTION OF THE DIAGNOSTIC/MASTER EXAM

The multiple-choice section of the Diagnostic/Master exam follows. You have seen the questions in the “walk through” in Chapter 3.

Advanced Placement Literature and Composition

Section 1

Total time—1 hour

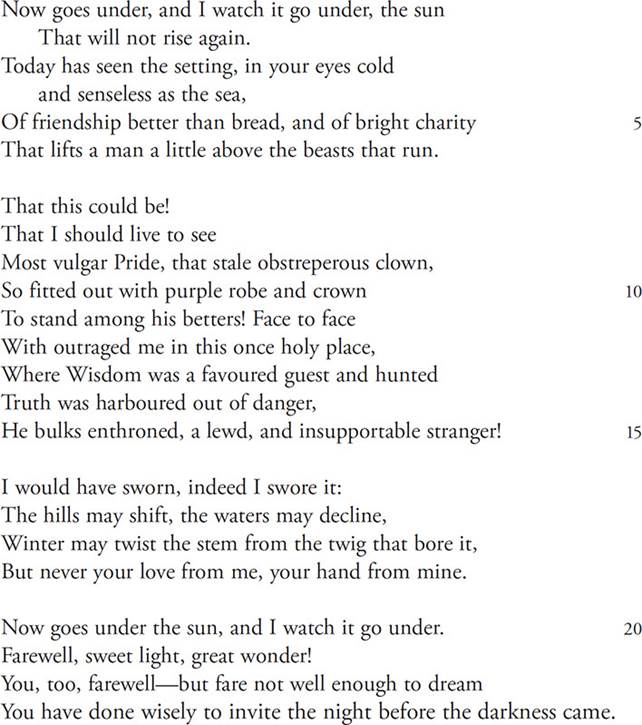

Carefully read the following passages and answer the accompanying questions. Questions 1—10 are based on the following poem.

Now Goes Under . . .

by Edna St. Vincent Millay

1. The poem is an example of a(n)

A. sonnet

B. lyric

C. ode

D. ballad

E. dramatic monologue

2. The setting of the sun is a symbol for

A. the beginning of winter

B. encountering danger

C. the end of a relationship

D. facing death

E. the onset of night

3. The second stanza is developed primarily by

A. metaphor

B. simile

C. personification

D. hyperbole

E. allusion

4. “He” in line 15 refers to

A. Wisdom

B. Truth

C. I

D. Pride

E. charity

5. According to the speaker, what separates man from beast?

A. love

B. friendship

C. charity

D. truth

E. wisdom

6. For the speaker, the relationship has been all of the following except

A. honest

B. dangerous

C. spiritual

D. ephemeral

E. nourishing

7. The reader can infer from the play on words in the last stanza that the speaker is

A. dying

B. frantic

C. wistful

D. bitter

E. capricious

8. “This once holy place” (line 12) refers to

A. the sunset

B. the relationship

C. the sea

D. the circus

E. the Church

9. The cause of the relationship’s situation is

A. a stranger coming between them

B. the lover not taking the relationship seriously

C. the lover feeling intellectually superior

D. the lover’s pride coming between them

E. the lover being insensitive

10. The speaker acknowledges the finality of the relationship in line(s)

A. 1—2

B. 7

C. 8

D. 16

E. 18—19

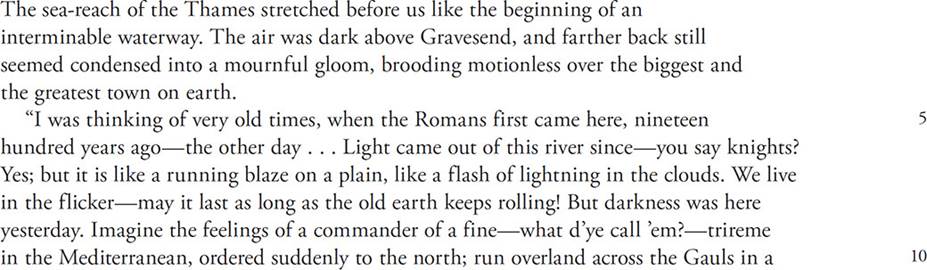

Questions 11—23 are based on the following passage.

11. In the passage, darkness implies all of the following except

A. the unknown

B. savagery

C. ignorance

D. death

E. exploration

12. The setting of the passage is

A. Africa

B. Ancient Rome

C. the Thames River

D. the Mediterranean

E. Italy

13. The tone of the passage is

A. condescending

B. indignant

C. scornful

D. pensive

E. laudatory

14. Later events may be foreshadowed by all of the following phrases except

A. “Imagine the feelings of a commander . . . ”

B. “ . . . live in the midst of the incomprehensible . . . ”

C. “ . . . in some inland post feel the savagery . . . ”

D. “They must have been dying like flies here.”

E. “ . . . the very end of the world . . . ”

15. The narrator draws a parallel between

A. light and dark

B. past and present

C. life and death

D. fascination and abomination

E. decency and savagery

16. In this passage, “We live in the flicker...” (lines 7—8) may be interpreted to mean ALL of the following EXCEPT

A. In the history of the world, humanity’s span on earth is brief.

B. Future civilizations will learn from only a portion of the past.

C. Periods of enlightenment and vision appear only briefly.

D. The river has been the source of life throughout the ages.

E. A moment of present-day insight about conquest.

17. One may conclude from the passage that the speaker

A. admires adventurers

B. longs to be a crusader

C. is a former military officer

D. recognizes and accepts the presence of evil in human experience

E. is prejudiced

18. In the context of the passage, which of the following phrases presents a paradox?

A. “The fascination of the abomination . . . ”

B. “ . . . in the hearts of wild men”

C. “There’s no initiation . . . into such mysteries”

D. “ . . . a flash of lightning in the clouds”

E. “ . . . death skulking in the air . . . ”

19. The lines “Imagine him here . . . concertina . . . ” (lines 13—14) contain examples of

A. hyperbole and personification

B. irony and metaphor

C. alliteration and personification

D. parallel structure and simile

E. allusion and simile

20. According to the speaker, the one trait which saves Europeans from savagery is

A. sentiment

B. a sense of mystery

C. brute force

D. religious zeal

E. efficiency

21. According to the speaker, the only justification for conquest is

A. the “weakness of others”

B. it’s being “proper for those who tackle a darkness . . . ”

C. their grabbing “what they could get for the sake of what was to be got”

D. “ . . . an unselfish belief in the idea . . . ”

E. “The fascination of the abomination . . . ”

22. In the statement by the speaker, “Mind, none of us would feel exactly like this” (line 36), “this” refers to

A. “ . . . a Buddha preaching in European clothes . . . ” (lines 35—36)

B. “ . . . imagine the growing regrets . . . the hate.” (lines 31—32)

C. “What redeems it is the idea only.” (lines 45—46)

D. “ . . . think of a decent young citizen in a toga . . . ” (line 24)

E. “I was thinking of very old times . . . ” (line 5)

23. The speaker presents all of the following reasons for exploration and conquest except

A. military expeditions

B. “ . . . a chance of promotion”

C. “ . . . to mend his fortunes”

D. religious commitment

E. punishment for a crime

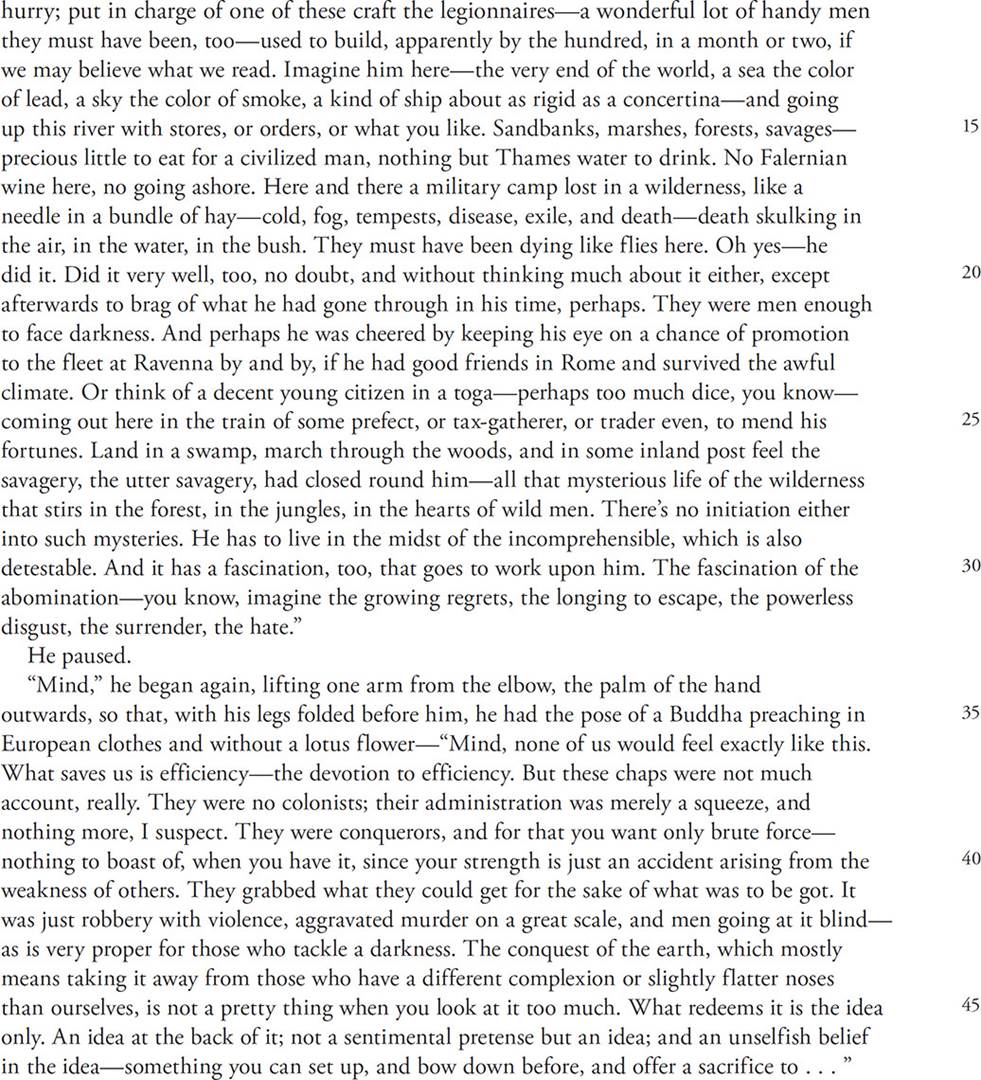

Questions 24—35 are based on the following poem.

24. “That time of year” (line 1) refers to

A. youth

B. old age

C. childhood

D. senility

E. maturity

25. “Death’s second self” (line 8) refers to

A. “That time of year”

B. “sunset fadeth”

C. “the west”

D. “ruin’d choirs”

E. “black night”

26. Line 12 is an example of

A. paradox

B. caesura

C. parable

D. hyperbole

E. metonymy

27. “Twilight of such day” (line 5) is supported by all of the following images except

A. “sunset fadeth”

B. “the glowing of such fire”

C. “west”

D. “Death’s second self”

E. “ashes of his youth”

28. “This thou perceiv’st” (line 13) refers to

A. the beloved’s deathbed

B. the sorrow of unrequited love

C. the passion of youth expiring

D. the beloved’s acknowledgment of the speaker’s mortality

E. the speaker sending the lover away

29. The poem is an example of a(n)

A. elegy

B. Spenserian sonnet

C. Petrarchan sonnet

D. Shakespearean sonnet

E. sestina

30. The poem is primarily developed by

A. metaphor

B. argument

C. synecdoche

D. alternative choices

E. contradiction

31. The irony of the poem is best expressed in line

A. 5

B. 7

C. 10

D. 11

E. 14

32. “It” in line 12 can best be interpreted to mean

A. a funeral pyre

B. spent youth

C. the intensity of the speaker’s love

D. the impending departure of his beloved

E. the immortality of the relationship

33. An apt title for the poem could be

A. Love Me or Leave Me

B. Death Be Not Proud

C. The End Justifies the Means

D. Love’s Fall

E. Grow Old Along with Me

34. The tone of the poem can best be described as

A. contemplative

B. defiant

C. submissive

D. arbitrary

E. complaining

35. The speaker most likely is

A. jealous of the beloved’s youth

B. pleased that the lover will leave

C. unable to keep up with the young lover

D. unwilling to face his own mortality

E. responsive to the beloved’s constancy

Questions 36—47 are based on the following passage.

Poets and Language

by Percy Bysshe Shelley

36. The passage is an example of

A. the opening of a novel

B. the opening of an autobiography

C. an essay

D. an ode

E. a dramatic monologue

37. According to Shelley, a poet is a combination of

A. historical figure and patriot

B. artist and priest

C. grammarian and poet

D. sculptor and musician

E. lawmaker and seer

38. In lines 5 and 6, “the germs of the flower and the fruit of latest time” can best be interpreted to mean

A. the guardian of the future

B. that the poet’s thoughts destroy conventional thinking

C. that the poet is clairvoyant

D. that the poet is the gardener of thought

E. that the current thoughts of the poet presage the future

39. According to Shelley, “the pretense of superstition” (lines 7—8) is

A. the ability to “foreknow” events

B. the ability to control the future

C. to grant immortality to the poet

D. to be a legislator

E. the ability to change the future

40. Shelley asserts that grammatical forms (lines 10{{#}}8211;15) serve all the following purposes except

A. to indicate verb tense

B. to clarify pronoun agreement

C. to solidify relative pronouns

D. to forbid citation

E. to enhance poetry

41. The reader may infer that the book of Job and the works of Aeschylus and Dante

A. are too far in the past to be of value today

B. are examples of Shelley’s theories

C. have injured poetry

D. deal with superstition

E. are more decisive than art

42. According to Shelley, poetry, sculpture, music, and painting have what characteristic in common?

A. They are dependent on one another.

B. They rely on grammatical forms.

C. They are at odds with one another.

D. They are eternal.

E. They can only relate to a specific time and place.

43. In lines 19—20, the phrase “that imperial faculty, whose throne . . . ” refers to

A. legislators

B. language

C. synonyms

D. nature

E. poetry

44. According to Shelley, which of the following is not part of the nature of language?

A. It is imaginative.

B. It is a reflection of passion.

C. It causes civil habits of action.

D. It deals with the eternal self.

E. It is connected only to thought.

45. In line 27, if the word “former” refers to language, then “latter” refers to

A. art

B. motion

C. limits

D. imagination

E. metrics

46. Lines 27—28, beginning with, “The former . . .” contain ALL of the following literary devices EXCEPT

A. parallel structure

B. simile

C. imagery

D. personification

E. metaphor

47. According to the final paragraph, the greatest attribute of the poet is his

A. sensitivity to light and dark

B. depiction of fantasy and reality

C. perception of others

D. ability to reflect the future

E. creation of art

STOP.

THIS IS THE END OF THE MULTIPLE-CHOICE SECTION OF THE DIAGNOSTIC/MASTER EXAM

Answers and Explanations

Now Goes Under . . .

by Edna St. Vincent Millay

1. B. This question requires the student to know the characteristics of various poetic forms. (See Chapter 9.) Using the process of elimination, the correct answer B is readily confirmed. Lyric poetry is emotional and personal.

2. C. Although the setting sun is often associated with winter, death, and darkness, these answers are not symbolic of the literal topic of the poem—the end of the love relationship.

3. C. The poet uses personification in lines 9—15: “vulgar Pride,” “Where Wisdom was a favoured guest,” “hunted Truth” as characters to develop the conflicts apparent in the poem. [TIP: Capitalization of nouns often indicates personification.]

4. D. This is an antecedent question. The student must retrace the reference “He” back to its origins to locate the correct answer. Try asking “who is enthroned, lewd and unsupportable?” Since truth, charity, and wisdom are described positively, only vulgar pride qualifies as the answer.

5. C. This question requires you to find the antecedent. Ask yourself, “Who or what lifts man?” The answer, charity, should be obvious.

6. B. Sometimes you can find information from a previous question. In question 2, “danger” was eliminated as a choice; therefore, it probably wouldn’t be suitable for this question either. Try finding proof of the others. Truth = honest; holy = spiritual; bread = nourishment. Therefore, dangerous has to be the answer.

7. D. This is a tone question based on a repetitive contradictory phrase. She does not wish him well; therefore, she is bitter and resigned. There is nothing playful, wistful, or frantic in the conclusion.

8. B. This is a relationship question. You should realize this by the intensity of the opposing lewd force, pride, which destroyed the sanctity of the love. (If you see this, you could validate your answer to question 9.)

9. D. The cause is developed in the longest stanza, lines 7—15. Find the proof for your answer in lines 7—12.

10. A. Interestingly enough, the speaker reveals the conclusion in the first two lines of the poem. “The sun that will not rise again” establishes the totality of the circumstances.

Heart of Darkness

by Joseph Conrad

11. E. Here’s an easy question to start you off. For years you heard your English teachers and your classmates discussing all the elements that could be associated with darkness. All the choices given in this question would qualify except for exploration.

12. C. Line 1 gives you the answer. The Thames is the river that runs through the heart of London.

13. D. A careful reading of the passage will introduce you to a speaker who is thinking about the past, thinking about exploration and conquest, and thinking about the conqueror and the conquered.

14. A. Here, the speaker is asking his listeners to picture the past. Therefore, it is not pointing to the future. The feelings of a commander have nothing to do with a future event; whereas each of the other choices hints at a future concept.

15. B. The second paragraph is about ancient Rome and its conquests. The third paragraph has the speaker considering “us” and what saves “us.” This is past and present.

16. B. The first ten lines support inclusion of A. Choice B is NOT part of the speaker’s conversation. Choice C is supported in the second paragraph. Choice D may be found in lines 5—8. Lines 36—47 support Choice E.

17. D. Lines 26—30 and 39—45 indicate the speaker’s attitude toward the human condition. There is no evidence in the passage to support any of the other choices.

18. A. The question assumes you know the definition of paradox. Therefore, you should be able to see that to be fascinated by that which is repulsive, awful, and horrible is a paradox.

19. D. “A sea,” “a sky,” “a kind,” “or orders,” “or what” are examples of parallel structure. The simile is “ship about as rigid as a concertina.”

20. E. This is a straightforward, factual question. The answer is found in line 37.

21. D. In lines 45—47 the speaker is philosophizing about what it is that “redeems” the “conquest of the earth.” It is the idea.

22. B. This question asks you to locate the antecedent of “this.” You could use the substitution method here. Just replace “this” with the word or phrase. Or, you could look carefully at the text itself. The omniscient narrator is describing the speaker as a Buddha. Lines 45—46 come after “this.” D and E are not real possibilities. Also, they are too far away from the pronoun.

23. E. A careful reading of the passage allows you to find references to A and D and to locate the quoted phrases in B and C. What you will not find are any references to “punishment for a crime.”

Sonnet 73

by William Shakespeare

24. B. The difficulty with this question lies in the similarity between B and E. However, it should be apparent from the numerous references to death and the contrast to youth that the poet is speaking of a literal time period in life and not of a state of emotional development.

25. E. Use the process of substitution and work backward in the poem to find the antecedent. Recognize the appositive phrase, which is set off by commas, to spot the previous image{{#}}8212; “black night.” Another trick is to recast the line into a directly stated sentence instead of the poetic inversion. Asking “who or what is Death’s second self” will help you locate the subject of the line.

26. A. Once again you are being tested on terminology and your ability to recognize an example. Deconstruct the line and find its essence; here it is obvious that “consumed” and “nourished” are contradictory.

27. B. Even without returning to the poem, you should notice that A, C, D, and E suggest death or diminishment. The only image of intensity and life appears in choice B.

28. D. The keys to this question can be found in lines 10—12 and line 14, which restate the irony of the beloved’s devotion and the speaker’s mortality. A good technique is to always check the previous and subsequent lines in order to clarify your answer. Also, careful reading would eliminate A and B. Passion is not mentioned in the poem.

29. D. For the prepared student, this question is a giveaway. Definitions of these terms in Chapter 9 clarify the differences among the types of sonnets. The rhyme scheme should lead you to choose D.

30. A. The sonnet depends on several extended comparisons with nature{{#}}8212;the seasons, day and night, and fire. Although there may be a contradiction in the final three lines, the primary means of development is metaphor. (See Chapter 8 for examples of synecdoche.)

31. E. Since contradiction and paradox are techniques that create irony, you should be able to see that choice E restates the essential opposing forces in the sonnet.

32. C. You must reread and interpret the entire third quatrain to clearly figure out this question. You need to decode the metaphor and realize that fires must be fed and that they expire when they exhaust the source of fuel.

33. D. Even though E is a lovely thought, the speaker never expresses the desire to have the beloved age along with him. This answer depends on the pun in the title of choice D{{#}}8212;fall. Here it may refer to the season of age as well as to the decline of the speaker and the relationship. No other choice is supported in the sonnet.

34. A. At first glance, one might think the speaker is submissive to the greater force of death; however, at no time does he acquiesce to the demands of mortality. The speaker thinks about and reflects on his circumstances.

35. E. You should notice that three of the five choices are negative. If you have read carefully, you will be aware that the poem is laudatory and positive with regard to the depth of the beloved’s love. And, at no time is the speaker looking forward to his lover’s departure.

Poets and Language

by Percy Bysshe Shelley

36. C. This question is an example of how important the knowledge of definitions of literary terms is if you hope to do well on the AP Lit exam. Using your knowledge and experience, you would obviously choose C after reading just a few of the opening lines.

37. E. Lines 2—3 give you the answer to this factual question. You simply have to know a couple of synonyms for “legislators” and “prophets.”

38. E. Here, you are being asked to make some serious associations with germination and flowering of buds and plants that lead to the future production of fruit. Also, the word “latest” should lead you to choose E.

39. A. This question centers around a literary definition and requires you to look at the words preceding and following the given phrase. “Foreknow the spirit of events” and “attribute of prophecy” point only to A.

40. D. A careful reading of lines 10—15 will lead you to conclude that all choices except “forbid citation” can be seen as a function of grammatical forms. Citation is associated with the limits of the essay.

41. B. In line 14, “examples of this fact” refers to Aeschylus, the book of Job, and Dante. The word “examples” must lead you to choose B.

42. D. This is a rather difficult question. In lines 9—10, the reader is told that the poet participates in the eternal. Lines 11—12 state that grammatical forms will not injure poetry, and the reader is given examples of this. At the end of the paragraph, Shelley states that sculpture, etc. is even “more decisive,” meaning indicative of the eternal.

43. E. Simply, the antecedent of “that” is “poetry.” If in doubt, use substitution.

44. C. Lines 21—24 indicate all the characteristics given except for C.

45. A. This question demands nothing more than knowing the meanings of two words and locating an antecedent. To find the answer, you must go to the preceding sentence. In line 26, you will see the last item is “art.”

46. D. Comparing language to a mirror and all other materials to a cloud are examples of metaphor and simile being used to construct imagery. Comparing an inanimate object to a living being is not a part of this image.

47. D. Carefully read the words in lines 29—30, beginning with “the mirrors” and ending with “upon the present.” Here, Shelley compares poets to mirrors of the future. Mirrors reflect.