Writing Smart, 3rd edition - Princeton Review 2018

Lab reports

Why write a lab report?

Why does your teacher want you to write a lab report detailing your experiment anyway? You may think it is a sneaky way to prove that you have actually done the experiment. If, however, you take a moment to consider the parts of a lab report, you will see a larger truth emerge. You write a lab report so you can indicate your personal thought process as it relates to the experiment or study performed. For instance, you might have dissolved aspirin until it became wintergreen oil, but it makes no difference if you did this or exploded marshmallows in the microwave unless you understand why you did it, and what the results mean.

Experimentation is often misunderstood. You may have heard comments like, “The experiment was unsuccessful; we have failed in our mission.” Don’t worry about “failing.” An experiment is an attempt to discover how something will react in a given situation. Since you will always discover something, the experiment is always a success, even if what you find out annoys you. You write a lab report to say what you thought you might observe, then what you did observe, and what you think it all means. So whether you notice, like Sir Alexander Fleming, that there’s a tiny mold that’s destroying all the other stuff in your petri dish, or you notice that when you add substance A to substance B not a darn thing happens, you have something to write down and a great lab report to deliver. As long as you know why you were performing the experiment in the first place, and what the results show you, your experiment is a success.

Lab report format

While individual teachers or professors may have particular specifications, the general format for a lab report is as follows:

Purpose of experiment

This is the first paragraph of your report, and it contains exactly what it says. Why are you doing your experiment? What do you hope to find or discover? The answer to these questions is your purpose, which gives the experiment and your observations a context.

Materials

List the materials and their amounts in case someone wants to replicate your findings.

Step-by-step process of experiment

Write exactly what happened in chronological order: what actions you performed and what you observed to follow from these actions. When you have the opportunity, illustrate your process with detailed drawings. Some teachers will require that this section be laid out numerically as in step one, step two, and so on. Others will prefer that you present this section in paragraph form.

Outcome, discussion of outcome, conclusions

Here is where the purpose of your experiment and the observations come together. If the results were as you expected, say what that means and why the results are as they are. If the results were other than what you had expected, explain why, if you can. If you don’t know why you achieved the results you did, offer some hypotheses. Conclude with a statement indicating how this experiment and the results you observed furthered your understanding of what you studied.

Make sure you check this outline with the requirements of your class. Most lab reports will include at least these basic requirements.

Writing the lab report

Step 1: Decide on the experiment and read any background material

Usually, you write a lab report based on experiments you perform in school. If you have to select your own experiment, make it something you want to explore. Can too many fish sticks really make you sick? Which is better, Coke or Pepsi? What really happens when you put marshmallows in the microwave?

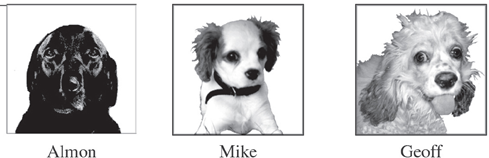

Nell, a brilliant and enterprising young scientist, will conduct her experiment at home because she is extremely motivated and was told she can earn extra credit by doing so. She has always had the feeling that her dogs understand what she says to them; now is her opportunity to test this out. She will attempt to discover whether dogs understand what people are saying. She has an eerie feeling they do, and she has planned an experiment to help her prove it. She has three dogs: Geoff, Almon, and Mike. She is going to use Geoff as the “control dog.” She will play Almon the same calming story every day, she will play Mike sad dog stories every day for five days, and she will simply observe Geoff at the same time each day, without playing any story. She will record the dogs’ responses daily.

If your experiment is assigned in class, you will probably be assigned a chapter to read. Read it! If you don’t know why you are conducting the experiment, you will have a tough time grasping the concepts, staying interested, and writing a decent lab report.

Step 2: Assemble your list of materials

When you are performing experiments, orderliness is extremely important. If you are not exact, your results will be suspect, so try to be careful. Write down everything you have set up before you start your process. Be sure to include any exact measurements for mass, weight, or volume, for example.

Nell takes out her notebook and writes down the following:

Almon (Chocolate Lab)

Mike (Lovable mutt)

Geoff (Spaniel)

Recordings (audiobooks) of happy stories for dogs

Recordings (audiobooks) of sad stories for dogs

Phone, tablet, or laptop to play the recordings

Notebook for observations

Special closed-off room for observations

Step 3: Perform your experiment while taking notes

To write a complete lab report you must make accurate observations while you perform your experiment, even if that means just writing down, “The mixture is turning blue and fizzy, it is overflowing out of the beaker, the desk has caught fire, must go.” Be as descriptive and accurate as possible; these notes will form the bulk of your report.

Nell marks Day 1 in her notebook, and takes Almon into the observation room where she plays a recording of See Spot Run. She marks down everything Almon does. She then removes Almon and repeats the process for Mike, playing him the same story, and then takes Geoff into the room and observes him without playing a story. On Day 2, she plays See Spot Run for Almon, one of the unhappy dog stories for Mike, and again no story for Geoff. For the next five days, she plays See Spot Run for Almon, a different sad dog story for Mike, and no story at all for Geoff, noting that Mike seems to get happier and happier, and Almon seems to become more agitated. She marks down these observations and ponders them.

Step 4: Write it

Once you have performed the experiment and taken notes, writing your lab report will be straightforward. Follow this format: write the introduction and purpose of the experiment, then the materials, then the observations, and finally the conclusions and any commentary.

DOGS AND LITERATURE

by Nell

The purpose of my experiment was to test whether my dogs can, as I believe they can, understand what I say to them. I tested this theory by recording three dogs’ responses to calming texts read aloud, both calming and upsetting texts read aloud, and no texts read. Three dogs, Geoff, Almon, and Mike were my subjects. Geoff was not read to at all, Almon was read a soothing dog text—See Spot Run—and Mike was read a variety of sad dog texts. All the dogs’ reactions were monitored to determine whether they corresponded to the text read. The hypothesis was that if the dogs understood what they heard, they should have been fine and relaxed throughout the calm text, upset by the upsetting text, and unaffected by the absence of any text.

SUBJECTS AND MATERIALS

Mike—Lovable mutt, aged 2 years, weight 15 pounds.

Almon—Chocolate Lab, aged 2 years, 6 months, weight 60 pounds.

Geoff—Spaniel, aged 3 years, weight 21 pounds.

Recordings of:

· See Spot Run—happy dog story

· Cujo—sad dog story

· Champ, Gallant Collie—sad dog story

· The Spotted Dotted Puppy—sad dog story

· 101 Dalmatians—sad dog story (ultimate triumph excluded)

Figure 1

PROCEDURE

Day 1

Almon: Played See Spot Run, a happy dog story, for 15 minutes. Almon walked around room for 4 minutes, scratched himself for 7.5 minutes, yawned 4 times, wagged his tail for 3.5 minutes.

Mike: Played See Spot Run for 15 minutes. Received same general responses, 8 minutes of scratching, 5 minutes of walking around room sniffing things, 3 minutes of tail-wagging, and 5 yawns.

Geoff: Played no story recording and did not speak to him. He napped for 15 minutes.

Day 2

Almon: Played See Spot Run for Almon for 15 minutes. Almon walked and sniffed for 5 minutes this time, scratched himself for 6 minutes, yawned twice, and stood and wagged his tail for 4 minutes.

Mike: Played Spotted Dotted Puppy, a story of conformity and abandonment in the animal world. Mike trotted around the room for 8 minutes, wagging his tail, then scratched himself for the remainder of the time (7 minutes). Yawned 3 times.

Geoff: Played no story recording and did not speak to him. He napped for 15 minutes.

Day 3

Almon: Played See Spot Run for Almon for 15 minutes. Almon walked around the room for 2 minutes, and then stopped and started growling at the tape recorder during the section in which Jane sees Spot run. The growling continued for 6 minutes, after which Almon started yelping and whining, for 5 minutes. The final 2 minutes Almon alternately scratched his ear vigorously and whined.

Mike: Played Champ, Gallant Collie. Watched closely, particularly the section in which Champ is attacked by a mountain lion and almost loses an entire herd of sheep. Mike walked and sniffed for 7 minutes, yawned 3 times, wagged his tail for 6 minutes, and scratched himself for 3 minutes.

Geoff: Played no story recording and did not speak to him. He napped, woke up after 8.5 minutes, yawned, and returned to napping.

Day 4

Almon: [Note: Almon seemed reluctant to enter the room today.] Played See Spot Run for Almon for 15 minutes. There was no tail-wagging at all for the second day in a row, and a repetition of yesterday’s growling episode lasted for 11 minutes. The final 4 minutes consisted of Almon lying on the floor and shuffling along on his front paws, whining.

Mike: Played Mike Cujo for 15 minutes. Paid particular attention to the section in which Cujo suffers a tragic accident. Mike trotted around the room for 8 minutes, wagging his tail, then scratched himself for the remainder of the time (7 minutes). Yawned 3 times.

Geoff: Played no story recording and did not speak to him. He napped for 15 minutes.

Day 5

Almon: Almon was highly reluctant to enter the listening room today. Played See Spot Run for Almon for 15 minutes. Almon spent the entire 15 minutes howling.

Mike: Played Mike 101 Dalmatians, the excerpt in which Cruella de Vil outlines her plans to make a coat from puppy skins. Mike sniffed and walked for 5.5 minutes, sat and wagged his tail for 5.5 minutes, and rested for 4 minutes, yawning 3 times.

Geoff: Played no story recording and did not speak to him. He napped for 15 minutes.

CONCLUSION

The results were not exactly what I had anticipated. I hypothesized that hearing the upsetting stories would affect Mike in such a way that he expressed anxiety, yet he remained essentially the same day after day. Almon, on the other hand, whom I expected to remain the same, as he was being read the same story day after day, expressed extreme anxiety. Geoff remained the same every day; from this I can infer that no outside influence (such as a storm coming or a change in diet) accounted for the responses of Almon and Mike. I conclude from this that dogs probably don’t understand the words they are being read. However, I believe this experiment justifies further research as to whether dogs recognize repetitive sounds, as was so clearly demonstrated by Almon’s response to See Spot Run day after day. Thus, though I cannot say I have proven that dogs understand English, I can say that I have opened the door to future scientific inquiry.

Step 5: Proofread

Check back to see that all illustrations and charts are correctly numbered and easily understood. Check for spelling, grammar, and punctuation. Also make sure that the purpose of the experiment is clear, and that your conclusion is well-founded.

Common lab report pitfalls

Overly technical language

Many students and novice science writers fall into the trap of thinking that science writing must be loaded with technical terms. Not so! Like all other writing, science writing is meant to be read. And you can bet your instructor will want to read a report that is clear and to the point.

Not having a unique perspective

Finding out what happens when you pour sulfuric acid over a candy bar, or whatever your particular experiment is, can be really interesting. That’s why scientists of old started all of this: they wanted to know what would happen. Sure, everyone else in the class might be doing the same experiment, but your perspective and interest in the result are your own. If you show interest in your subject and experiment, your lap report will be more engaging for the reader.

Lack of visuals

The great thing about lab reports is that, unlike most academic writing, you can insert figures and diagrams. Don’t let this opportunity escape you!

Lack of purpose

The point of a lab report is to present your experiment and why you performed it; if you do not know your purpose or if you are unable to convey your purpose in writing, your lab report will make little sense. There are some who write a lab report without this crucial knowledge, so their lab reports become an odd listing of things they did in science class that day, without any understanding of why they did them. Don’t let this happen. Start by looking at the material your teacher or professor gave you with your lab assignment. Why do they want you to do the assignment? If you don’t know, ask questions. Then create an outline, including a description of the experiment and why you performed it. Did everything happen the way you had expected or predicted it would? If not, why do you think that might be? Know what you what you want to say before you start writing, and your lab report will be much easier to write.

Format and style for lab reports

Format

Some lab reports accept a numbered list of steps rather than a sentence-by-sentence paragraph for the procedures section. Follow any directions provided by your teacher or professor regarding format.

Rough drafts

Generally, lab reports do not go through the rigorous draft process to which essays and research papers are subjected. Before you hand your lab report in, you should still proofread it for any possible errors, but the full-fledged stylistic editing process is generally used more on scientific research papers, which are formatted like regular research papers and are edited as such.

Title

Always include a title page. It gives you the opportunity to clearly lay out your topic right away as well as use visual aids.

References

Unless your instructor requests one, there is generally no need to supply a bibliography or any other list of sources. If you do use a quote from someone’s work, provide the name of the author and the title in parentheses within the report.

In conclusion…

Lab reports benefit from lucid prose—that is, clear, organized writing. Your reports will shine when you understand your experiment before you begin writing and express what you mean as clearly as you can.

Recommended reading

The following books discuss science in a clear exciting way understandable to the non-scientist. Read, enjoy, and emulate.

Isaac Asimov, Isaac Asimov’s Guide to Earth and Space, Fawcett.

Rachel Carson, Silent Spring, Houghton Mifflin.

James Gleick, Chaos, The Penguin Group.

Stephen Jay Gould, Bully for Brontosaurus, Norton.

David MacCauley, The Way Things Work, Houghton Mifflin.

John McPhee, In Suspect Terrain, The Noonday Press.

Lewis Thomas, The Lives of a Cell, Bantam Books.

Lewis Thomas, The Medusa and the Snail, G.K. Hall and Company.