Writing Smart, 3rd edition - Princeton Review 2018

Project proposals

So you need to write a project proposal…

Maybe you need to present a business idea to your boss. Or maybe you are applying for a grant and need to outline your project to demonstrate how worthwhile and why it deserves funding. A project proposal is a written description of your project along with a rationale for why it should be undertaken or funded.

Whatever the occasion for your proposal, don’t panic. The process of writing a project proposal is relatively straightforward; all you need is a good idea, a plan, and enthusiasm.

Project proposal format

Introduction

The introduction should state how your idea came to be. If your project is to satisfy some hole in the array of products in the world, here you can write, “It was always clear to me that there were not enough different types of cookie jars in the world.” Then, describe your project and how it will address that need.

Body of proposal

This section will always be divided into three parts.

1. The Idea: A summary of your idea

2. Your Plan: What you will do once your project is approved

3. You: Your particular qualifications for the task or project

While not absolutely necessary, you may want to itemize the costs and other financial needs of your project in this section as well. This will show your employer or whoever is reading this proposal that you are doing your homework.

Conclusion

Wrap up your proposal with a convincing argument for why your idea is a great one, and include a graceful sign-off.

Writing the project proposal

Step 1: Create an outline

You first need to organize your thoughts, and as we have discussed elsewhere in this book, the best way to do that is to write an outline. An outline for a project proposal gives you a chance to write down your idea and lay out your plan for selling it.

Lisa and Mimi have an idea; they want someone to give them money so they can travel around the world for a few years by boat, having a wonderful time. They call this project the Sailing Sisters. They estimate they need $5 million. They want to write the proposal together, which makes it a collaborative project. Yet they have no fear; they know that if you start with a clear plan, collaborative writing can be less work and more fun than writing alone.

To begin, both Lisa and Mimi write outlines, which they will then compare and meld into one.

Lisa’s outline

I. Introduction: Why? There aren’t enough women having fun out there; there is a great need for a few raise-hell women.

A. Evidence for this, success of Thelma and Louise, the movie of women raising hell

B. People’s undying interest in the antics of supermodels

C. Success of “Absolutely Fabulous,” British television series in which a couple of hellions tear up the town

D. Sailing Sisters: we want to have fun.

II. Idea: Mimi and I on a boat with plenty of money and a radio; the possibilities are endless

. A couple of scenarios? Mimi and I swim in the Aegean, Mimi and I disrupt a boring meeting and create an international incident, Mimi and I skydive in Venezuela.

A. When we get the money, we buy the boat and set sail.

B. Why us? Mimi has sailed before; we are ready for this kind of fun.

III. Costs: How much the boat, the food, etc. will cost

IV. Conclusion: How great it will be to have this need filled and how worthy a cause it is

Mimi’s outline

I. Introduction

Why? There is no record of women taking a trip like this.

Idea: Sailing Sisters—Lisa and I take a boat and sail and sail and sail, island to island, then write a book.

II. Idea

A. The Plan: We outline the plan of going from island to island, starting on Martha’s Vineyard, then south, then east. Give an example of the kind of entry we would write.

B. With the money we first do research about other island-to-island boat jaunts throughout history, then buy a boat, then itinerary.

C. Why us? We are interested in women and history and the history of travel; we can do the island-to-island thing with a historical perspective; we can write a book about it.

III. Conclusion: How worthy it would be to have this kind of travel history done by women, right now!

Lisa and Mimi get together and compare notes. Their outlines are so different! Their ideas for the trip are so divergent! Or are they? They spend some time discussing the particulars of each of their proposals. Do they really want to make a book of this? Is it for fun or for historical importance, and is there a difference between these two goals?

This discussion and comparison of goals is of the utmost importance for anyone planning a collaborative writing project. It allows you to compare ideas and really come up with a common focus, before the bulk of the writing is done.

Lisa and Mimi first try to decide whether they really do want to write a book about their adventures. Mimi confesses that she included that section in her outline because she wanted to sound worthier of funding. Lisa says that, actually, they don’t need to sound worthy of funding, they are worthy of funding. Why pretend to be scholars when they are not? They have other attributes, and their project is not about books.

Next to be decided is the perspective of the trip. Is it for fun or for history? Again, they talk about what they really want to do. They decide that what they really want is not to talk about travel but to have some fun. They ponder all of this for some time and decide to focus on the hell-raising women aspect of the trip; they want to do this to have a good time, so why shouldn’t that be their strength? And, after all, they want to be honest about the funding they seek. Mimi volunteers to write the final outline for the proposal, which Lisa will then check over.

Final outline

I. Introduction

Why: There is a great need for images of women being daring and reckless. The public is hungry for it, witness.

A. Success of Thelma and Louise, the movie of women raising hell

B. People’s undying interest in the antics of supermodels

C. Success of “Absolutely Fabulous,” British television series in which a couple of hellions tear up the town

Therefore: We will go on a no-holds-barred ocean-going tour.

II. Plan

Idea: We will buy a sailboat and adventure across the open seas, inspiring all who hear tell of us.

Scenarios:

. Skydiving in Venezuela

A. Swimming in the Aegean

B. Barging into a meeting and creating an international incident

How: With the funds we receive, we will buy a boat and go where the winds take us.

Why us: We have the time, the inclination, and the wild-woman credentials.

III. Conclusion: It’s really a great idea.

Step 2: Check your outline

Read your outline and determine if it gives you a clear writing plan. Do you know the gist of what you want to get across? Do you understand what you will write? If so, continue. If not, rework your outline until it fulfills these guidelines.

Step 3: Gather your data and write a rough draft

A good project proposal is one that is based on diligent research and reflects that diligent research. If you are competing with others for a project, point out your strengths, supporting your points with hard data. If you are demonstrating a need for stuffed-crust pizza that you are going to fill, note that there were over one million calls for stuffed-crust pizza recorded by Pizza Palace.

Once you have gathered as many facts and figures as you can—by using any information source that occurs to you—you can begin writing. Writing a project proposal is much like writing a research paper. You follow your outline, paragraph by paragraph, and put together a rough draft to work from. When you are working collaboratively, you might assign one person research and the other writing. Another possibility is to assign separate sections of the outline to each person. For instance, the introduction and the idea sections might go to one person, and the conclusion and the other body paragraphs to the other. This second option can be difficult when you are putting the whole proposal together, because often people have different writing styles; putting the pieces together will require you to make the whole proposal stylistically uniform. Choose the best option based on your group’s strengths and weaknesses. For example, the stronger public speaker should do the talking, and the more skilled writer should do the writing. Try to determine this division of labor ahead of time, as negotiations in the middle of writing can make an already difficult task more trying.

Mimi and Lisa decide that Lisa will be responsible for the research, and Mimi will write the proposal, which will then be edited and revised by Lisa. Lisa goes to the library and finds books about adventuring women, women sailors, and sea-going. She calls the Motion Picture Association of America and finds out how many people went to see Thelma and Louise. Meanwhile, Mimi sits on the veranda, sips lemonade, and thinks of convincing images to put in her writing. When Lisa has accumulated enough facts, she gives her copious and well-organized notes to Mimi, who then goes inside to her laptop.

Step 4: Edit

Edit your proposal, aiming to make it professional, convincing, and clear. You know what to do, and if you need reminding, look back to the editing guidelines in Chapter 4.

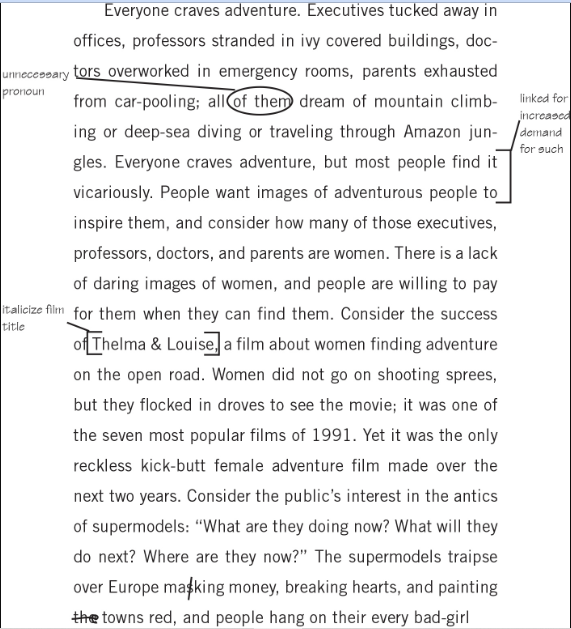

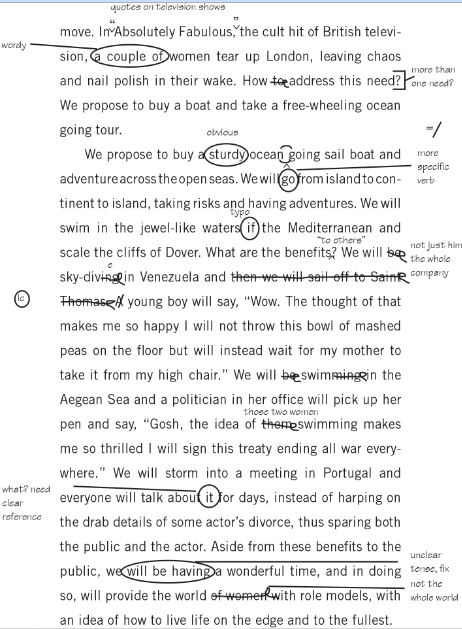

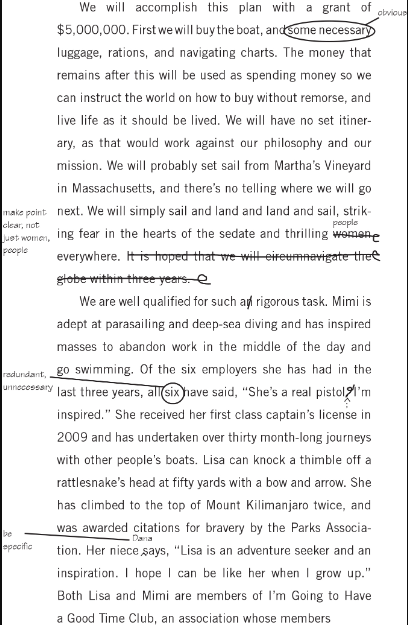

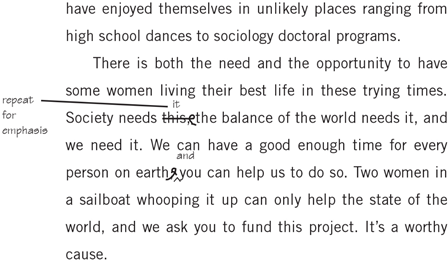

One more time! Edit Mimi’s rough draft, checking for clarity, organization, and brevity. When you’re done, see if Lisa’s edits agree with yours.

Rough draft

Everyone craves adventure. Executives tucked away in offices, professors stranded in ivy covered buildings, doctors overworked in emergency rooms, parents exhausted from car-pooling; all of them dream of mountain climbing or deep-sea diving or traveling through Amazon jungles. Everyone craves adventure, but most people find it vicariously. People want images of adventurous people to inspire them, and consider how many of those executives, professors, doctors and parents are women. There is a lack of daring images of women, and people are willing to pay for them when they can find them. Consider the success of Thelma & Louise, a film about women finding adventure on the open road. Women did not go on shooting sprees, but they flocked in droves to see the movie; it was one of the seven most popular films of 1991. Yet it was the only reckless kick-butt female adventure film made over the next two years. Consider the public’s interest in the antics of supermodels: “What are they doing now? What will they do next? Where are they now?” The supermodels traipse over Europe masking money, breaking hearts and painting the towns red, and people hang on their every bad-girl move. In Absolutely Fabulous, the cult hit of British television, a couple of women tear up London, leaving chaos and nail polish in their wake. How to address this need? We propose to buy a boat and take a free-wheeling ocean going tour.

We propose to buy a sturdy ocean going sail boat and adventure across the open seas. We will go from island to continent to island, taking risks and having adventures. We will swim in the jewel-like waters if the Mediterranean and scale the cliffs of Dover. What are the benefits? We will be sky-diving in Venezuela and then we will sail off to Saint Thomas. A young boy will say, “Wow. The thought of that makes me so happy I will not throw this bowl of mashed peas on the floor but will instead wait for my mother to take it from my high chair.” We will be swimming in the Aegean Sea and a politician in her office will pick up her pen and say, “Gosh, the idea of them swimming makes me so thrilled I will sign this treaty ending all war everywhere.” We will storm into a meeting in Portugal and everyone will talk about it for days, instead of harping on the drab details of some actor’s divorce, thus sparing both the public and the actor. Aside from these benefits to the public, we will be having a wonderful time, and in doing so, will provide the world of women with role models, with an idea of how to live life on the edge and to the fullest.

We will accomplish this plan with a grant of $5,000,000. First we will buy the boat, and some necessary luggage, rations, and navigating charts. The money that remains after this will be used as spending money so we can instruct the world on how to buy without remorse, and live life as it should be lived. We will have no set itinerary, as that would work against our philosophy and our mission. We will probably set sail from Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts, and there’s no telling where we will go next. We will simply sail and land and land and sail, striking fear in the hearts of the sedate and thrilling women everywhere. It is hoped that we will circumnavigate the globe within three years.

We are well qualified for such an rigorous task. Mimi is adept at parasailing and deep-sea diving and has inspired masses to abandon work in the middle of the day and go swimming. Of the six employers she has had in the last three years, all six have said, “She’s a real pistol. I’m inspired.” She received her first class captain’s license in 2009 and has undertaken over thirty month-long journeys with other people’s boats. Lisa can knock a thimble off a rattlesnake’s head at fifty yards with a bow and arrow. She has climbed to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro twice, and was awarded citations for bravery by the Parks Association. Her niece says, “Lisa is an adventure seeker and an inspiration. I hope I can be like her when I grow up.” Both Lisa and Mimi are members of I’m Going to Have a Good Time Club, an association whose members have enjoyed themselves in unlikely places ranging from high school dances to sociology doctoral programs.

There is both the need and the opportunity to have some women living their best life in these trying times. Society needs this, the balance of the world needs it, and we need it. We can have a good enough time for every person on Earth; you can help us to do so. Two women in a sailboat whooping it up can only help the state of the world, and we ask you to fund this project. It’s a worthy cause.

Edited version by lisa

Step 5: Put it all together

Your proposal should be as professional as possible, so double-check for typos, grammar, and spelling mistakes. The language should be clear and convincing while conveying your enthusiasm for the project at hand.

The title page of your proposal should indicate to the recipients what they are to expect, and from whom. You should also include information on how the recipients can get in touch with you, though that same information should be included in your cover letter; see Chapter 8 on professional letters.

Keys to the success of a proposal are much like those of a business letter: brevity and knowledge of your audience. The cover letter for a proposal should be no longer than one page, and it should include a brief description of the project and the amount of money requested. Also mention any significant prior contact with the funding source, if relevant, and why you chose to approach this particular individual or organization.

Lisa and Mimi have discussed the edits made on the previous pages and implemented them. They have rewritten the awkward sentences and cleaned up all typos and spelling. Their proposal, which follows, is now ready to go. Note that in your own proposal, you should rely more on facts and figures than they have here; for their project these were not as relevant.

Sailing Sisters

A Proposal for a Round-the-World Voyage

Submitted by Lisa Smith and Mimi Smith

Everyone craves adventure. Executives tucked away in offices, professors stranded in ivy-covered buildings, doctors overworked in emergency rooms, parents exhausted from car-pooling: all dream of mountain-climbing or deep-sea diving or traveling through Amazon jungles. Everyone craves adventure, but most people find it vicariously. Consider the demand this creates for images of adventure to inspire them. Then consider how many of those executives, professors, doctors, and parents are women. There is a lack of daring images of women, and people are willing to pay for them when they can find them. Consider the success of Thelma and Louise, a film about women finding adventure on the open road. Women did not go on shooting sprees, but they flocked in droves to see the movie; it was one of the seven most popular films of 1991. Yet it was the only reckless kick-butt female adventure film made over the next two years. Consider the public’s interest in the antics of supermodels: “What are they doing now? What will they do next? Where are they now?” The supermodels traipse over Europe making money, breaking hearts, and painting towns red, and people hang on their every bad-girl move. In “Absolutely Fabulous,” the cult hit of British television, a pair of women tear up London, leaving chaos and nail polish in their wake. How can we address these needs? We propose to buy a boat and take a freewheeling oceangoing tour.

We propose to buy an oceangoing sailboat and adventure across the open seas. We will sail from island to continent to island, taking risks and having adventures. We will swim in the jewel-like waters of the Mediterranean and scale the cliffs of Dover. What are the benefits to the rest of the world? We will sky-dive in Venezuela, and a young boy will say, “Wow. The thought of that makes me so happy I will not throw this bowl of mashed peas on the floor but will instead wait for my mother to take it from my high chair.” We will swim in the Aegean Sea and a politician in her office will pick up her pen and say, “Gosh, the idea of those two women swimming makes me so thrilled I will sign this treaty ending all war everywhere.” We will storm into a meeting in Portugal and everyone will talk about the spectacle for days, instead of harping on the drab details of some actor’s divorce, thus sparing both the public and the actor. Aside from these benefits to the public, we will have a wonderful time, and in doing so, will provide the world with role models, with an idea of how to live life on the edge and to the fullest.

We will accomplish this plan with a grant of $5,000,000. First we will buy the boat, luggage, rations, and navigating charts. The money that remains after this will be used as spending money so we can instruct the world on how to buy without remorse, and live life as it should be lived. We will have no set itinerary, as that would work against our philosophy and our mission. We will probably set sail from Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts, and there’s no telling where we will go next. We will simply sail and land, and land and sail, striking fear in the hearts of the sedate, and thrilling people everywhere.

We are well qualified for such a rigorous task. Mimi is adept at parasailing and deep-sea diving and has inspired masses to abandon work in the middle of the day and go swimming. Of the six employers she has had in the last three years, all have said, “She’s a real pistol. I’m inspired.” She received her first-class captain’s license in 2009 and has undertaken over thirty month-long journeys with other people’s boats. Lisa can knock a thimble off a rattlesnake’s head at fifty yards with a bow and arrow. She has climbed to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro twice, and was awarded citations for bravery by the Parks Association. Her niece Dana says, “Lisa is an adventure seeker and an inspiration. I hope I can be like her when I grow up.” Both Lisa and Mimi are members of I’m Going to Have a Good Time Club, an association whose members have enjoyed themselves in unlikely places ranging from high school dances to sociology doctoral programs.

There is both the need and the opportunity to have some women living their best life in these trying times. Society needs it, the balance of the world needs it, and we need it. We can have a good enough time for every person on earth, and you can help us do so. Two women in a sailboat whooping it up can only help the state of the world, and we ask you to fund this project. It’s a worthy cause.

Step 6: Submit your proposal

Don’t go overboard with your presentation; just make sure what you submit is neat and professional.

Common project proposal pitfalls

Insufficient evidence

When you write a project proposal, you must sell your idea, and as with all selling, the buyer is constantly wary of being taken advantage of. Give buyers, or readers, sufficient evidence; your enthusiasm must be backed up with facts.

No visuals

Charts, graphs, and photographs contribute to a proposal’s professional look, and break up the text to make it more interesting. Charts are also a great way to present hard data and statistics, which can help your case and convince your audience more readily.

Lack of professionalism

If you do not appear entirely capable and organized, your audience is unlikely to trust you. Remember, you are asking readers to give you either money or control of some project, all of which makes recipients understandably nervous. It is your job to convince them of your reliability and capability.

Wrong audience

Know your audience. If you are trying to sell a book about your experiences in the wilderness, don’t send your proposal to a crossword puzzle publisher. This affects the way you write the proposal as well. Are you trying to convince an arts commissioner? Then your proposal should focus on that aspect of your work.

Lack of enthusiasm

If you truly believe your idea is exciting, make sure your enthusiasm is conveyed. Most businesses receive hundreds of proposals, so yours should stand out.

Format and style for project proposals

Always provide a title page

This should include to whom the proposal is being submitted, and your name, address, and where you can be reached. If it is a group project, it should list the name of the group or association proposing the project, as well as the name of one person to contact for questions and correspondence.

Footnote all references

The more documented evidence you have, the more creditable and impressive your proposal will be.

Charts, graphs, and illustrations

Be sure to assign any figures a number (e.g., Figure 1) so you can refer to them clearly in the text.

In conclusion…

Like any type of writing, the best project proposals are clear, cogent, and backed up by research. As long as you take the time to organize and carefully edit your presentation, you should be able to put together a proposal that presents your ideas clearly and convinces a reader that you are the proper one for any job, project, or funding.

Recommended reading

The following books are written especially for the business writer, and are invaluable for their information on structure, style, and presentation.

William Paxson, The Business Writing Handbook, Bantam Books, 1981.

William Paxson, Principles of Style for the Business Writer, Dodd, Mead & Company, 1985.