Practical argument: A text and anthology - Laurie G. Kirszner, Stephen R. Mandell 2019

Proposal arguments

Strategies for argument

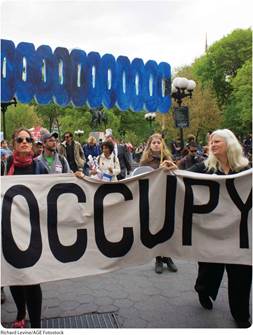

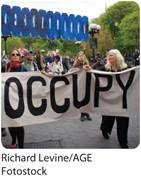

Protesters rallied in New York on April 25, 2012, the day that student loan debt reached $1 trillion. The protesters’ proposals include debt forgiveness and no-interest student loans.

AT ISSUE

Should the Government Do More to Relieve the Student-Loan Burden?

In 2011, the protest movement Occupy Wall Street began in New York City’s Zuccotti Park. Initially, the protestors focused on economic problems like inequality and unemployment. But other issues emerged, including a demand for student-loan forgiveness. Soon after, then-President Barack Obama announced a program of student-loan relief. For example, he reduced the maximum required payment on loans from 15 percent to 10 percent of a borrower’s annual income. Since taking office in 2017, President Donald Trump has proposed his own reforms. But regardless of political party, policymakers agree that student debt—now over $1.5 trillion—is a problem.

According to some experts, the debt is a financial bubble that will eventually burst and cause more damage than the 2008 housing crisis. Many critics claim that reforms to the current student-loan program miss the root cause of the problem: the ever-increasing cost of tuition. In response, they propose restructuring federal aid in a way that rewards schools that reduce expenses and penalize schools that do not. Others argue that most students receive enough money from traditional grants and loans to offset tuition; in their view, the “crisis” is overblown. Still others say that students should simply realize that they must live up to their obligations and repay their loans.

Later in this chapter, you will be asked to think more about this issue. You will be given several sources to consider and asked to write a proposal argument that takes a position on whether the government should do more to relieve the student-loan burden.

What Is a Proposal Argument?

When you write a proposal argument, you suggest a solution to a problem. The purpose of a proposal argument is to convince people that a problem exists and that your solution is both feasible and worthwhile.

Proposal arguments are the most common form of argument. You see them every day on billboards and in advertisements, editorials, and letters to the editor. The problems proposal arguments address can be local:

§ What steps should the community take to protect its historic buildings?

§ How can the city promote the use of public transportation?

§ What can the township do to help the homeless?

§ What should be done to encourage recycling on campus?

§ How can community health services be improved?

The problems addressed in proposal arguments can also be more global:

§ Should the United States increase its military budget?

§ What should be done to increase clean energy production?

§ What can countries do to protect themselves against terrorism?

§ What should be done to decrease gun violence?

§ How can we encourage the ethical treatment of animals?

The poster shows the photo of Charlize Theron with a dog. The text above the photo reads, “If you wouldn’t wear your dog (ellipsis) please don’t wear any fur.” By Charlize Theron. A text box at the bottom right portion of the poster reads, The only difference between your “best friend” and animals killed for their fur is how we treat them. All animals feel pain and suffer when trappers and farmers break their necks or electrocute them for their pelts. Learn more at (bold) PETA.org (end bold). The Peta logo is at the bottom left portion of the poster.

PROBLEM-SOLVING STRATEGIES

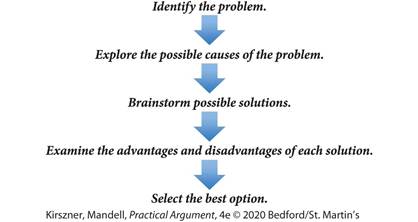

Because the purpose of a proposal argument is to solve a problem, you should begin by considering both the problem and its significance. By following a simple step-by-step process (alone or in a group), you can analyze the problem and develop effective strategies for solving it.

The text at the top of the diagram reads, Identify the problem. An arrow from it points to the text, Explore the possible causes of the problem. An arrow from this text points to the text, Brainstorm possible solutions. An arrow from this text points to the text, Examine the advantages and disadvantages of each solution. An arrow from this text points to the text, Select the best option.

Remember, problem solving is a process. If you solve the problem, you can begin to plan your proposal. If not, you should begin the problem-solving process again, perhaps modifying the problem or its possible solutions.

Stating the Problem

When you write a proposal argument, you should begin by demonstrating that a problem exists. In some cases, readers will be familiar with the problem, so you will not have to explain it in great detail. For example, it would not take much to convince students at your university that tuition is high or that some classrooms are overcrowded. Most people also know about the need to provide affordable health care to the uninsured or to reduce the rising level of student debt because these are problems that have received a good deal of media attention.

Other, less familiar issues need more explanation—sometimes a great deal of explanation. In these cases, you should not assume that readers will accept (or even understand) the importance of the problem you are discussing. For example, why should readers care about the high dropout rate at a local high school? You can answer this question by demonstrating that this problem affects not only the students who drop out but others as well:

§ Students who do not have high school diplomas earn substantially less than those who do.

§ Studies show that high school dropouts are much more likely to live in poverty than students who complete high school.

§ Taxpayers pay for the social services that dropouts often require.

§ Federal, state, and local governments lose the taxes that dropouts would pay if they had better jobs.

When you explain the situation in this way, you show that a problem that appears to be limited to just a few individuals actually affects society as a whole.

How much background information you need to provide about a problem depends on how much your readers already know about it. In many cases, a direct statement of a problem is not enough: you need to explain the context of the problem and then discuss it with this context in mind. For example, you cannot simply say that the number of databases to which your college library subscribes needs to be increased. Why does it need to be increased? How many new databases should be added? Which ones? What benefits would result from increasing the number of databases? What will happen if the number is not increased? Without answers to these questions, readers will not be able to understand the full extent of the problem. (Statistics, examples, personal anecdotes, and even visuals can also help you demonstrate the importance of finding a solution to the problem.) By presenting the problem in detail, you draw readers into your discussion and motivate them to want to solve it.

Proposing a Solution

After you have established that a problem exists, you have to propose a solution. Sometimes the solution is self-evident, so that you do not need to explain it in much detail. For example, if you want to get a new computer for the college newspaper, you do not have to give a detailed account of how you intend to purchase it. On the other hand, if your problem is more complicated—for example, proposing that your school should sponsor a new student organization—you will have to go into much more detail, possibly listing the steps that you will take to implement your plan as well as the costs associated with it.

Demonstrating That Your Solution Will Work

When you present a solution to a problem, you have to support it with evidence—facts, examples, and so on from your own experience and from research. You can also point to successful solutions that are similar to the one you are suggesting. For example, if you were proposing that the government should do more to relieve the student-loan burden, you could list the reasons why certain changes would be beneficial for many students. You might also point to student-friendly practices in other countries, such as Great Britain and Australia. Finally, you could use a visual, such as a chart or a graph, to help you support your position.

You also have to consider the consequences—both intended and unintended—of your proposal. Idealistic or otherwise unrealistic proposals almost always run into trouble when skeptical readers challenge them. If you think, for example, that the federal government should increase subsidies on electric cars to encourage clean energy, you should consider the effects of such subsidies. How much money would drivers actually save? How would the government make up the lost revenue? What programs would suffer because the government could no longer afford to fund them? In short, do the benefits of your proposal outweigh its negative effects?

Establishing Feasibility

Your solution not only has to make sense but also has to be feasible—that is, it has to be practical. Sometimes a problem can be solved, but the solution may be almost as bad as—or even worse than—the problem. For example, a city could drastically reduce crime by putting police on every street corner, installing video cameras at every intersection, and stopping and searching all cars that contain two or more people. These actions would certainly reduce crime, but most people would not want to live in a city that instituted such authoritarian policies.

Even if a solution is desirable, it still may not be feasible. For example, although expanded dining facilities might improve life on campus, the cost of a new student cafeteria would be high. If paying for it means that tuition would have to be increased, many students would find this proposal unacceptable. On the other hand, if you could demonstrate that the profits from the increase in food sales in the new cafeteria would offset its cost, then your proposal would be feasible.

Discussing Benefits

By presenting the benefits of your proposal, you can convince undecided readers that your plan has merit. How, for example, would students benefit from an expansion of campus parking facilities? Would student morale improve because students would get fewer parking citations? Would lateness to class decline because students would no longer have to spend time looking for a parking spot? Would the college earn more revenue from additional parking fees? Although not all proposals list benefits, many do. This information can help convince readers that your proposal has merit and is worth implementing.

Refuting Opposing Arguments

You should always assume that any proposal—no matter how strong—will be objectionable to some readers. Moreover, even sympathetic readers will have questions that they will want answered before they accept your ideas. That is why you should always anticipate and refute possible objections to your proposal. For example, if the federal government did more to relieve the student-loan burden, would some students try to take advantage of the program by borrowing more than they need? Would all students be eligible for help, even those from wealthy families? Would this proposal be fair to students who have already paid off their loans? Would students who worked while attending school be eligible? If any objections are particularly strong, concede them: admit that they have merit, but point out their shortcomings. For instance, you could concede that some students might try to abuse the program, but you could then point out that only a small minority of students would do this and recommend steps that could be taken to address possible abuses.

![]()

EXERCISE 16.1 SUPPORTING THESIS STATEMENTS

List the evidence you could present to support each of these thesis statements for proposal arguments.

1. Because many Americans are obese, the government should require warning labels on all sugared cereals.

2. The United States should ban all gasoline-burning cars in ten years.

3. Candidates for president should be required to use only public funding for their campaigns.

4. Teachers should carry handguns to protect themselves and their students from violence.

5. To reduce prison overcrowding, states should release all nonviolent offenders.

![]()

EXERCISE 16.2 IDENTIFYING PROBLEMS

Review the proposals in Exercise 16.1, and list two problems that each one could create if implemented.

![]()

EXERCISE 16.3 ANALYZING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

Read the following opinion column, “Why Medicare-for-All Is Good for Business” by Bernie Sanders. What problem does Sanders discuss? How does he propose to solve this problem? What benefits does he expect his solution to have? What evidence could he have added to strengthen his proposal?

WHY MEDICARE-FOR-ALL IS GOOD FOR BUSINESS

BERNIE SANDERS

This opinion column was published in Fortune on August 21, 2017.

Despite major improvements made by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), our health care system remains in crisis. Today, we have the most expensive, inefficient, and bureaucratic health care system in the world. We spend almost $10,000 per capita each year on health care, while the Canadians spend $4,644, the Germans $5,551, the French $4,600, and the British $4,192. Meanwhile, our life expectancy is lower than most other industrialized countries and our infant mortality rates are much higher.

Further, as of September 2016, 28 million Americans were uninsured and millions more underinsured with premiums, deductibles, and copayments that are too high. We also pay, by far, the highest prices in the world for prescription drugs.

The ongoing failure of our health care system is directly attributable to the fact that it is largely designed not to provide quality care in a cost-effective way, but to make maximum profits for health insurance companies, the pharmaceutical industry, and medical equipment suppliers. That has got to change. We need to guarantee health care for all. We need to do it in a cost-effective way. We need a Medicare-for-all health care system in the U.S.

“We need to guarantee health care for all. We need to do it in a cost-effective way.”

Let’s be clear. Not only is our dysfunctional health care system causing unnecessary suffering and financial stress for millions of low- and middle-income families, it is also having a very negative impact on our economy and the business community—especially small- and medium-sized companies. Private businesses spent $637 billion on private health insurance in 2015 and are projected to spend $1.059 trillion in 2025.

But it’s not just the heavy financial cost of health care that the business community is forced to bear. It is time and energy. Instead of focusing on their core business goals, small- and medium-sized businesses are forced to spend an inordinate amount of time, energy, and resources trying to navigate an incredibly complex system in order to get the most cost-effective coverage possible for their employees. It is not uncommon for employers to spend weeks every year negotiating with private insurance companies, filling out reams of paperwork, and switching carriers to get the best deal they can.

And more and more business people are getting tired of it and are asking the simple questions that need to be addressed.

Why as a nation are we spending more than 17 percent of our GDP on health care, while nations that we compete with provide health care for all of their people at 9, 10, or 11 percent of their GDP? Is that sustainable? What impact does that have on our overall economy?

Why are employers who do the right thing and provide strong health care benefits for their employees at a competitive disadvantage with those who don’t? Why are some of the largest and most profitable corporations in America, like Walmart, receiving massive subsidies from the federal government because their inadequate benefits force many of their employees to go on Medicaid? Why are most labor disputes in this country centered on health care coverage? Is it good for a company to have employees on the payroll not because they enjoy the work, but because their families need the health insurance the company provides?

Richard Master is the owner and CEO of MCS Industries Inc., the nation’s leading supplier of wall and poster frames—a $200 million a year company based in Easton, Pa. “My company now pays $1.5 million a year to provide access to health care for our workers and their dependents,” Master told Common Dreams. “When I investigated where all the money goes, I was shocked.”

What he found was that fully 33 cents of every health care premium dollar “has nothing to do with the delivery of health care.” Thirty-three percent of his health care budget was being spent on administrative costs.

“I came to realize that insurers comprise a completely unnecessary middleman that not only adds little if any value to our health care system, it adds enormous costs to it,” Master said.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Every other major country on earth has a national health care program that guarantees health care to all of their people at a much lower cost. In our country, Medicare, a government-run single-payer health care system for seniors, is a popular, cost-effective health insurance program. When the Senate gets back into session in September, I will be introducing legislation to expand Medicare to cover all Americans.

This is not a radical idea. I live in Burlington, Vt., 50 miles south of the Canadian border. For decades, every man, woman, and child in Canada has been guaranteed health care through a single-payer, publicly funded health care program. Not only has this system improved the lives of the Canadian people, it has saved businesses many billions of dollars.

The American Sustainable Business Council, a business advocacy organization, started a campaign in April in support of single-payer health care. To date, more than 170 business leaders have signed on to this initiative in more than 30 states.

Here is what these business leaders have written:

All supporters of the campaign believe that a single-payer health care system, which is what the vast majority of the industrialized world embraces, will deliver significant cost-savings, in large part by eliminating the wasteful practices of the insurance industry that are designed for financial advantage.

In my view, health care for all is a moral issue. No American should die or suffer because they lack the funds to get adequate health care. But it is more than that. A Medicare-for-all single-payer system will be good for the economy and the business community.

![]()

EXERCISE 16.4 RESPONDING TO A PROPOSAL

Write a paragraph or two in which you argue for or against the recommendations Sanders proposes in “Why Medicare-for-All Is Good for Business.” Be sure to present a clear statement of the problems he is addressing as well as the strengths or weaknesses of his proposal.

Structuring a Proposal Argument

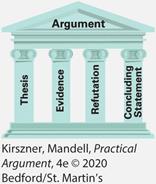

In general, a proposal argument can be structured in the following way:

§ Introduction: Establishes the context of the proposal and presents the essay’s thesis

§ Explanation of the problem: Identifies the problem and explains why it needs to be solved

§ Explanation of the solution: Proposes a solution and explains how it will solve the problem

§ Evidence in support of the solution: Presents support for the proposed solution (this section is usually more than one paragraph)

§ Benefits of the solution: Explains the positive results of the proposed course of action

§ Refutation of opposing arguments: Addresses objections to the proposal

§ Conclusion: Reinforces the main point of the proposal; includes a strong concluding statement

COLLEGES NEED HONOR CODES

MELISSA BURRELL

![]() The following student essay contains all the elements of a proposal argument. The student who wrote this essay is trying to convince the college president that the school should adopt an honor code—a system of rules that defines acceptable conduct and establishes procedures for handling misconduct.

The following student essay contains all the elements of a proposal argument. The student who wrote this essay is trying to convince the college president that the school should adopt an honor code—a system of rules that defines acceptable conduct and establishes procedures for handling misconduct.

Text reads as follows:

First paragraph: Today’s college students are under a lot of pressure to do well in school, to win tuition grants, to please teachers and family, and to compete in the job market. As a result, the temptation to cheat is greater than ever. At the same time, technology, particularly the internet, has made cheating easier than ever. Colleges and universities have tried various strategies to combat this problem, from increasing punishments to using plagiarism-detection tools such as Turnitin.com. However, the most comprehensive and effective solution to the problem of academic dishonesty is an honor code, a campus-wide contract that spells out and enforces standards of honesty. To fight academic dishonesty, colleges should institute and actively maintain honor codes (a corresponding margin note reads, Thesis statement).

Second paragraph: Although the exact number of students who cheat is impossible to determine, 68 percent of the students in one recent survey admitted to cheating (Musto). Some students cheat by plagiarizing entire papers or stealing answers to tests. Many other students commit so-called lesser offenses, such as collaborating with others when told to work alone, sharing test answers, cutting and pasting material from the internet, or misrepresenting data. All of these acts are dishonest; all amount to cheating. Part of the problem, however, is that students are often unsure whether (text continues on the next page and a corresponding margin note reads, Explanation of the problem: Cheating).

Second paragraph reads as follows:

their decisions are or are not ethical (Dimon). Because they are unclear about expectations and overwhelmed by the pressure to succeed, students can easily justify dishonest acts.

Third paragraph: An honor code solves these problems by clearly presenting the rules and by establishing honesty, trust, and academic honor as shared values. According to recent research, “setting clear expectations, and repeating them early and often, is crucial” (Grasgreen). Schools with honor codes require every student to sign a pledge to uphold the honor code. Ideally, students write and manage the honor code themselves, with the help of faculty and administrators. According to Timothy M. Dodd, however, to be successful, the honor code must be more than a document; it must be a way of thinking. To accomplish this, all first-year students should receive copies of the school’s honor code at orientation. At the beginning of each academic year, students should be required to reread the honor code and renew their pledge to uphold its values and rules. In addition, students and instructors need to discuss the honor code in class. (Some colleges post the honor code in every classroom.) In other words, Dodd believes that the honor code must be part of the fabric of the school. It should be present in students’ minds, guiding their actions and informing their learning and teaching. (A corresponding margin note reads, Explanation of the solution: Institute honor code.)

Fourth paragraph: Studies show that serious cheating is 25 to 50 percent lower at schools with honor codes (Dodd). With an honor code in place, students cannot say that they do not know what constitutes cheating or that they do not understand what will happen to them if they cheat. Studies also show that in schools with a strong honor code, instructors are more likely to take action against cheaters. One study shows that instructors frequently do not confront students who cheat because they are not sure the university will back them up (Vandehey, Diekhoff, and LaBeff 469) and another suggests that students are more likely to cheat when they feel their instructor will be lenient (Hosny and Fatima 753). When a school has an honor code, however, instructors can be certain that both the students and the school will support their actions. (A corresponding margin note reads, Evidence in support of the Solution.)

Fifth paragraph: When a school institutes an honor code, a number of positive results occur. First, an honor code creates a set of basic rules that students can follow. Students know in advance what is expected of them and what will happen if they commit an infraction. In addition, an honor code promotes honesty, placing more responsibility and power in the (text continues on the next page and a corresponding margin note reads, Benefits of the solution).

Fifth paragraph continues as follows:

hands of students and encouraging them to act according to a higher standard. As a result, schools with honor codes often permit unsupervised exams that require students to monitor one another. Finally, according to Dodd, honor codes encourage students to act responsibly. They assume that students will not take unfair advantage of each other or undercut the academic community. As Dodd concludes, in schools with honor codes, plagiarism (and cheating in general) becomes a concern for everyone—students as well as instructors.

Sixth paragraph: Some people argue that plagiarism-detection tools such as Turnitin .com are more effective at preventing cheating than honor codes. However, these tools focus on catching individual acts of cheating, not on preventing a culture of cheating. When schools use these tools, they are telling students that their main concern is not to avoid cheating but to avoid getting caught. As a result, these tools do not deal with the real problem: the decision to be dishonest. Rather than trusting students, schools that use plagiarism-detection tools assume that all students are cheating. Unlike plagiarism-detection tools, honor codes fight dishonesty by promoting a culture of integrity, fairness, and accountability. By assuming that most students are trustworthy and punishing only those who are not, schools with honor codes set high standards for students and encourage them to rise to the challenge. (A margin note corresponding to the paragraph reads, Refutation of opposing 6 arguments.)

Seventh paragraph: The only long-term, comprehensive solution to the problem of cheating is campus-wide honor codes. No solution will completely prevent dishonesty, but honor codes go a long way toward addressing the root causes of this problem. The goal of an honor code is to create a campus culture that values and rewards honesty and integrity. By encouraging students to do what is expected of them, honor codes help create a confident, empowered, and trustworthy student body (a corresponding margin note reads, Concluding statement).

Works Cited

Dimon, Melissa. “Why Students Cheat—And What to Do About It.” Edutopia, 17 Apr. 2018. https://www.edutopia.org/article/why-students-cheat-and-what-do-about-it.

Dodd, Timothy M. “Honor Code 101: An Introduction to the Elements of Traditional Honor Codes, Modified Honor Codes and Academic Integrity Policies.” Center for Academic Integrity, Clemson U, 2010, www.clemson.edu/ces/departments/mse/academics/honor-code.html.

Grasgreen, Allie. “Who Cheats, and How.” Inside Higher Ed, 16 Mar. 2012, www.insidehighered.com/news/2012/03/16/arizona-survey-examines-student-cheating-faculty-responses.

Hosny, Manar and Shameem Fatima. “Attitude of Students towards Cheating and Plagiarism: University Case Study.” Journal of Applied Sciences, vol. 14, no. 8, 2014, pp. 748—57.

Musto, Pete. “How Many College Students Admit to Cheating?” VOA, 1 Dec. 2018. https://www.voanews.com/a/how-many-college-students-admit-to-cheating/4095674.html.

Vandehey, Michael, et al. “College Cheating: A Twenty Year Follow-Up and the Addition of an Honor Code.” Journal of College Student Development, vol. 48, no. 4, July/August 2007, pp. 468—80. Academic OneFile, go

" aria-describedby="image06-desc4f1u4"/>

GRAMMAR IN CONTEXT

Will versus Would

Many people use the helping verbs will and would interchangeably. When you write a proposal, however, keep in mind that these words express different shades of meaning.

· Will expresses certainty. In a list of benefits, for example, will indicates the benefits that will definitely occur if the proposal is accepted.

o First, an honor code will create a set of basic rules that students can follow.

o In addition, an honor code will promote honesty.

· Would expresses probability. In a refutation of an opposing argument, for example, would indicates that another solution could possibly be more effective than the one being proposed.

o Some people argue that a plagiarism-detection tool such as Turnitin.com would be simpler and a more effective way of preventing cheating than an honor code.

![]()

EXERCISE 16.5 ANALYZING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

The following essay, “The Road to Fear-Free Biking in Boston” by Michelle Wu, includes the basic elements of a proposal argument. Read the essay, and answer the questions that follow it, consulting the outline on page 571 if necessary.

THE ROAD TO FEAR-FREE BIKING IN BOSTON

MICHELLE WU

This opinion column appeared in the Boston Globe on July 12, 2016.

I don’t own a bicycle. But I recently reclaimed my inner cyclist as part of the Boston Green Ribbon Commission’s Climate Innovations study tour to Northern Europe. Our agenda included experiencing sustainable mobility with a bicycle tour of Copenhagen, voted world’s best city for cyclists.

You might expect Cycling City to be a mecca of Lycra on wheels. But among the hundreds of riders on the road, no one looked like a Boston bicyclist, suited up for commuter battle.

“Stress-free city cycling? Never heard of it.”

Our tour guide, Niels, was helmet-less and dressed in a sharp blue suit. Spandex and gear, he explained, are for exercise cycling in the countryside. On the daily commute to work or school, the Danish take it easy, with relaxed, stress-free city cycling.

Stress-free city cycling? Never heard of it.

My head filled with flashbacks to the two previous bike tours I’ve joined in Boston: sweaty hands gripping handlebars where Massachusetts Avenue meets Columbia Road in a six-way intersection; silent prayers as cars zoomed by too close for comfort on River Street in Mattapan.

Crash fear is all too often justified in Greater Boston. In the first four months of 2016, 8 people were killed and 307 injured from crashes on Boston streets, up 20 percent compared to the same period in 2015. Last month, another fatal crash in Cambridge underscored the urgency of VisionZero and making our streets safe for all.

Many of these crashes are entirely preventable with street design that puts a buffer between cars and bikes—called “protected bike lanes’’ or “cycle tracks.” Separating cars from cyclists also makes pedestrians safer, with less sidewalk riding, slower vehicle speeds, shorter crossing distances, and safer intersections.

Pedaling through Copenhagen, I saw that safety is just the baseline benefit of world-class cycling infrastructure. When every street has bike lanes shielded from cars by a curb or median, cyclists ride without fear, and more people become cyclists: women, seniors, even kids riding alongside their parents. Safe infrastructure means cycling becomes an affordable transportation option open to all.

In Copenhagen, cyclists make up 45 percent of all commuters, and city planners have quantified the benefits. Adding up costs avoided by reducing traffic congestion, noise, crashes, wear and tear on infrastructure, and air pollution, they estimate 64 cents of net social gain from every mile traveled by bike instead of car. More residents getting regular exercise drives down health care costs by an estimated 61 cents per mile cycled.

But fitness and sustainability won’t motivate commuters to abandon their cars. To get nonprofessional riders on bicycles, cities must make bike commutes safe and convenient. In Copenhagen, cycle tracks receive top priority for snow clearance, followed by pedestrian sidewalks, then car lanes. Every detail of street design accommodates cyclists, from separately timed bicycle signals to plentiful bike parking at train stations.

Boston’s streets, on the other hand, are designed for conflict. Painted bike lanes function as space for double-parked delivery trucks, pushing cyclists into traffic. Posted signs and “sharrows” unrealistically ask drivers and cyclists to get along. The result is that only 1.9 percent of Boston commuters are willing to risk a bicycle trip—the bravest and most aggressive cyclists, who often provoke anxiety and rage in drivers.

We can do better.

Mayor Walsh and the Boston Transportation Department are leading a comprehensive effort to engage residents in planning our transportation future. We must reimagine our streets as spaces for all, not just cars.

For Boston, the urgency goes well beyond safety. Our continued economic growth depends on solving our transportation crunch. With a struggling public transit system that won’t be expanding service anytime soon, already gridlocked roadways will have to absorb many of the more than hundred thousand additional commuters projected by 2030. Carving out space for protected bike lanes is the most cost-effective way to increase our transit capacity and move more people on our streets.

To be clear, building a seamless and convenient network of protected cycling infrastructure will require trade-offs. On many streets, adding a cycle track means narrowing or removing car lanes, or eliminating on-street parking—scenarios that bring panic to car and business owners. Although research suggests that retail sales actually increase after switching parking for protected bike lanes, the proposals rarely see support from abutters. Yet we must acknowledge that our current transportation situation isn’t working for all residents, and it will worsen unless we take bold action to empower more affordable and sustainable options.

We can solve the car-bike conflict, and the solution unlocks a brighter, more inclusive economic and environmental future for Boston.

Identifying the Elements of a Proposal Argument

1. What is the essay’s thesis statement? How effective do you think it is?

2. Where in the essay does Wu identify the problem she wants to solve?

3. According to Wu, why is Copenhagen a model for Boston?

4. Where does Wu present her solutions to the problems she identifies?

5. Where does Wu discuss the benefits of her proposal? What other benefits could she have addressed?

6. Where does Wu address possible arguments against her proposal? What other arguments might she have addressed? How would you refute each of these arguments?

7. Evaluate the essay’s concluding statement.

![]()

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

Should the Government Do More to Relieve the Student-Loan Burden?

Reread the At Issue box on page 563, which gives background on whether the government should do more to relieve the student-loan burden. Then, read the sources on the following pages.

As you read this material, you will be asked to answer questions and to complete some simple activities. This work will help you understand both the content and structure of the selections. When you are finished, you will be ready to write a proposal argument that makes a case for or against having the government do more to relieve the student-loan burden.

SOURCES

Rana Foroohar, “The US College Debt Bubble Is Becoming Dangerous,” page 579 |

Richard Vedder, “Forgive Student Loans?,” page 582 |

Ben Miller, “Student Debt: It’s Worse than We Imagined,” page 585 |

Astra Taylor, “A Strike against Student Debt,” page 587 |

Sam Adolphsen, “Don’t Blame the Government,” page 590 |

Visual Argument: “Student Debt Crisis Solution,” page 593 |

THE US COLLEGE DEBT BUBBLE IS BECOMING DANGEROUS

RANA FOROOHAR

This op-ed appeared in Financial Times on April 9, 2017.

Rapid run-ups in debt are the single biggest predictor of market trouble. So it is worth noting that over the past 10 years the amount of student loan debt in the US has grown by 170 percent, to a whopping $1.4tn—more than car loans, or credit card debt. Indeed, as an expert at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) recently pointed out to me, since 2008 we have basically swapped a housing debt bubble for a student loan bubble. No wonder NY Federal Reserve president Bill Dudley fretted last week that high levels of student debt and default are a “headwind to economic activity.”

In America, 44 million people have student debt. Eight million of those borrowers are in default. That’s a default rate which is still higher than pre-crisis levels—unlike the default rate for mortgages, credit cards, or even car loans.

“I was told to expect a $72,000 a year sticker fee for Ivy League and liberal arts colleges.”

Rising college education costs will not help shrink those numbers. While the headline consumer price index is 2.7 percent, between 2016 and 2017 published tuition and fee prices rose by 9 percent at four-year state institutions, and 13 percent at posher private colleges.

A large chunk of the hike was due to schools hiring more administrators (who “brand build” and recruit wealthy donors) and building expensive facilities designed to lure wealthier, full-fee-paying students. This not only leads to excess borrowing on the part of universities—a number of them are caught up in dicey bond deals like the sort that sunk the city of Detroit—but higher tuition for students. The average debt load individual graduates carry is up 70 percent over the past decade, to about $34,000.

Having just attended the first college preparation meeting at my daughter’s high school, where I was told to expect a $72,000 a year sticker fee for Ivy League and liberal arts colleges, I would feel lucky to get away with just that.

This is clearly, as Mr Dudley observed, a headwind to stronger consumer spending. Growing student debt has been linked to everything from decreased rates of first time home ownership, to higher rental prices, to lower purchases of white goods, and all the things that people buy to fill homes. Indeed, given their debt loads, I wonder how much of the “rent not buy” spending habits of Millennials are a matter of choice.

But there are even more worrisome links between high student debt loads and health issues like depression, and marital failures. The whole thing is compounded by the fact that a large chunk of those holding massive debt do not end up with degrees, having had to drop out from the stress of trying to study, work, and pay back massive loans at the same time. That means they will never even get the income boost that a college degree still provides—creating a snowball cycle of downward mobility in the country’s most vulnerable populations.

How did we get here? Extreme politics played a role. In the US, the Koch Brothers/Grover Norquist tax revolt camp of the Republican party has been waging a state by state war on public university funding for years now: states today provide about $2,000 less in higher education funding per student than before 2008, the lowest rate in 30 years.

Meanwhile, the subprime crisis cut the ability of parents to use home equity loans to pay for their children’s education (previously a common practice). This left the bulk of the burden to students, at a time when the unemployment rates for young people of all skill levels were rising.

The trend is not limited to the US, of course. In the UK and beyond, completely free post-secondary education is a thing of the past. Beleaguered governments are pushing more and more of the responsibility for the things that make a person middle class—education, healthcare, and pension—on to individuals.

What are the fixes? For starters, we should look closely at the for-profit sector, where default rates are more than double those at average private colleges. These institutions receive federal subsidies but typically spend a minuscule part of their budgets on instruction; in the US, nearly 50 percent goes to marketing to new students. It looks all too much like an educational Ponzi scheme.

Transparency is also key—the student loan market as a whole is hopelessly opaque. In one recent US study, only a quarter of first year college students could predict their own debt load to within 10 percent of the correct amount. Truth in lending documents would help, as would loan counseling paid for by colleges. Sadly, the agency that is leading the fight on both—the CFPB—is under attack from Trump himself.

But the administration will not be able to hide from the student debt bubble. In an eerie echo of the housing crisis, debt is already flowing out of the private sector, and into the public. Before 2007, most student loans were underwritten by banks or other private sector financial institutions. Today, 90 percent of new loans originate with the Department of Education. Socialization of risk continues to be the way America deals with its debt bubbles.

Would that we considered making college free, as Bernie Sanders suggested. Even Mr Dudley called this “a reasonable conversation.” That way we could socialize the benefits of education too.

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

1. What does Foroohar mean when she says, “we have basically swapped a housing debt bubble for a student loan bubble” (para. 1)?

2. In the first ten paragraphs of her essay, Foroohar examines the problems associated with the student loan situation. Why do you think she spent so much time discussing these problems?

3. In paragraphs 3 and 4, Foroohar discusses the increasing cost of college tuition, but she never says what colleges should do about this situation. Should she have? What suggestions could she have made?

4. In paragraph 5, Foroohar says that she has just attended a college preparation meeting at her daughter’s high school. Why does she include this information?

5. According to Foroohar, how can the loan problem be fixed? How convincing are her suggestions?

6. How optimistic is Foroohar about the government’s ability to solve the student-debt problem? How do you know?

7. In her conclusion, Foroohar raises the possibility of making college free. Is this an effective way for her to end her essay? Explain.

FORGIVE STUDENT LOANS?

RICHARD VEDDER

The blog entry was posted to National Review Online on October 11, 2011.

As the Wall Street protests grow and expand beyond New York, growing scrutiny of the nascent movement is warranted. What do these folks want? Alongside their ranting about the inequality of incomes, the alleged inordinate power of Wall Street and large corporations, the high level of unemployment, and the like, one policy goal ranks high with most protesters: the forgiveness of student-loan debt. In an informal survey of over 50 protesters in New York last Tuesday, blogger and equity research analyst David Maris found 93 percent of them advocated student-loan forgiveness. An online petition drive advocating student-loan forgiveness has gathered an impressive number of signatures (over 442,000). This is an issue that resonates with many Americans.

Economist Justin Wolfers recently opined that “this is the worst idea ever.” I think it is actually the second-worst idea ever—the worst was the creation of federally subsidized student loans in the first place. Under current law, when the feds (who have basically taken over the student-loan industry) make a loan, the size of the U.S. budget deficit rises, and the government borrows additional funds, very often from foreign investors. We are borrowing from the Chinese to finance school attendance by a predominantly middle-class group of Americans.

But that is the tip of the iceberg: Though the ostensible objective of the loan program is to increase the proportion of adult Americans with college degrees, over 40 percent of those pursuing a bachelor’s degree fail to receive one within six years. And default is a growing problem with student loans.

Further, it’s not clear that college imparts much of value to the average student. The typical college student spends less than 30 hours a week, 32 weeks a year, on all academic matters—class attendance, writing papers, studying for exams, etc. They spend about half as much time on school as their parents spend working. If Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa (authors of Academically Adrift) are even roughly correct, today’s students typically learn little in the way of critical learning or writing skills while in school.

“The sins of the loan program are many. Let’s briefly mention just five.”

Moreover, the student-loan program has proven an ineffective way to achieve one of its initial aims, a goal also of the Wall Street protesters: increasing economic opportunity for the poor. In 1970, when federal student-loan and grant programs were in their infancy, about 12 percent of college graduates came from the bottom one-fourth of the income distribution. While people from all social classes are more likely to go to college today, the poor haven’t gained nearly as much ground as the rich have: With the nation awash in nearly a trillion dollars in student-loan debt (more even than credit-card obligations), the proportion of bachelor’s-degree holders coming from the bottom one-fourth of the income distribution has fallen to around 7 percent.

The sins of the loan program are many. Let’s briefly mention just five.

· First, artificially low interest rates are set by the federal government—they are fixed by law rather than market forces. Low-interest-rate mortgage loans resulting from loose Fed policies and the government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac spurred the housing bubble that caused the 2008 financial crisis. Arguably, federal student financial assistance is creating a second bubble in higher education.

· Second, loan terms are invariant, with students with poor prospects of graduating and getting good jobs often borrowing at the same interest rates as those with excellent prospects (e.g., electrical-engineering majors at MIT).

· Third, the availability of cheap loans has almost certainly contributed to the tuition explosion—college prices are going up even more than health-care prices.

· Fourth, at present the loans are made by a monopoly provider, the same one that gave us such similar inefficient and costly monopolistic behemoths as the U.S. Postal Service.

· Free Application for Federal Student Aid

· Fifth, the student-loan and associated Pell Grant programs spawned the notorious FAFSAº form that requires families to reveal all sorts of financial information—information that colleges use to engage in ruthless price discrimination via tuition discounting, charging wildly different amounts to students depending on how much their parents can afford to pay. It’s a soak-the-rich scheme on steroids.

Still, for good or ill, we have this unfortunate program. Wouldn’t loan forgiveness provide some stimulus to a moribund economy? The Wall Street protesters argue that if debt-burdened young persons were free of this albatross, they would start spending more on goods and services, stimulating employment. Yet we demonstrated with stimulus packages in 2008 and 2009 (not to mention the 1930s, Japan in the 1990s, etc.) that giving people more money to spend will not bring recovery. But even if it did, why should we give a break to this particular group of individuals, who disproportionately come from prosperous families to begin with? Why give them assistance while those who have dutifully repaid their loans get none? An arguably more equitable and efficient method of stimulus would be to drop dollars out of airplanes over low-income areas.

Moreover, this idea has ominous implications for the macro economy. Who would take the loss from the unanticipated non-repayment of a trillion dollars? If private financial institutions are liable for some of it, it could kill them, triggering another financial crisis. If the federal government shoulders the entire burden, we are adding a trillion or so more dollars in liabilities to a government already grievously overextended (upwards of $100 trillion in liabilities counting Medicare, Social Security, and the national debt), almost certainly leading to more debt downgrades, which could trigger investor panic. This idea is breathtaking in terms of its naïveté and stupidity.

The demonstrators say that selfish plutocrats are ruining our economy and creating an unjust society. Rather, a group of predominantly rather spoiled and coddled young persons, long favored and subsidized by the American taxpayer, are complaining that society has not given them enough—they want the taxpayer to foot the bill for their years of limited learning and heavy partying while in college. Hopefully, this burst of dimwittery should not pass muster even in our often dysfunctional Congress.

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

1. According to Vedder, forgiveness of student debt is “the second-worst idea ever” (para. 2). Why? What is the worst idea?

2. In paragraphs 3—6, Vedder examines the weaknesses of the federally subsidized student-loan program. List some of the weaknesses he identifies.

3. Why do you think Vedder waits until paragraph 7 to discuss debt forgiveness? Should he have discussed it sooner?

4. Summarize Vedder’s primary objection to forgiving student debt. Do you agree with him? How would you refute his objection?

5. Throughout his essay, Vedder uses rather strong language to characterize those who disagree with him. For example, in paragraph 8, he calls the idea of forgiving student loans “breathtaking in terms of its naïveté and stupidity.” In paragraph 9, he calls demonstrators “spoiled and coddled young persons” and labels Congress “dysfunctional.” Does this language help or hurt Vedder’s case? Would more neutral words and phrases have been more effective? Why or why not?

6. How would Vedder respond to Astra Taylor’s solution to the student-loan crisis (p. 587)? Are there any points that Taylor makes with which Vedder might agree?

STUDENT DEBT: IT’S WORSE THAN WE IMAGINED

BEN MILLER

This commentary was published in the New York Times on August 26, 2018.

Millions of students will arrive on college campuses soon, and they will share a similar burden: college debt. The typical student borrower will take out $6,600 in a single year, averaging $22,000 in debt by graduation, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

There are two ways to measure whether borrowers can repay those loans: There’s what the federal government looks at to judge colleges, and then there’s the real story. The latter is coming to light, and it’s not pretty.

“The new data makes clear that the federal government overlooks early warning signs.”

Consider the official statistics: Of borrowers who started repaying in 2012, just over 10 percent had defaulted three years later. That’s not too bad—but it’s not the whole story. Federal data never before released shows that the default rate continued climbing to 16 percent over the next two years, after official tracking ended, meaning more than 841,000 borrowers were in default. Nearly as many were severely delinquent or not repaying their loans (for reasons besides going back to school or being in the military). The share of students facing serious struggles rose to 30 percent over all.

Collectively, these borrowers owed over $23 billion, including more than $9 billion in default.

Nationally, those are crisis-level results, and they reveal how colleges are benefiting from billions in financial aid while students are left with debt they cannot repay. The Department of Education recently provided this new data on over 5,000 schools across the country in response to my Freedom of Information Act request.

The new data makes clear that the federal government overlooks early warning signs by focusing solely on default rates over the first three years of repayment. That’s the time period Congress requires the Department of Education to use when calculating default rates.

At that time, about one-quarter of the cohort—or nearly 1.3 million borrowers—were not in default, but were either severely delinquent or not paying their loans. Two years later, many of these borrowers were either still not paying or had defaulted. Nearly 280,000 borrowers defaulted between years three and five.

Federal laws attempting to keep schools accountable are not doing enough to stop loan problems. The law requires that all colleges participating in the student loan program keep their share of borrowers who default below 30 percent for three consecutive years or 40 percent in any single year. We can consider anything above 30 percent to be a “high” default rate. That’s a low bar.

Among the group who started repaying in 2012, just 93 of their colleges had high default rates after three years and 15 were at immediate risk of losing access to aid. Two years later, after the Department of Education stopped tracking results, 636 schools had high default rates.

For-profit institutions have particularly awful results. Five years into repayment, 44 percent of borrowers at these schools faced some type of loan distress, including 25 percent who defaulted. Most students who defaulted between three and five years in repayment attended a for-profit college.

The secret to avoiding accountability? Colleges are aggressively pushing borrowers to use repayment options known as deferments or forbearances that allow borrowers to stop their payments without going into delinquency or defaulting. Nearly 20 percent of borrowers at schools that had high default rates at year five but not at year three used one of these payment-pausing options.

The federal government cannot keep turning a blind eye while almost one-third of student loan borrowers struggle. Fortunately, efforts to rewrite federal higher-education laws present an opportunity to address these shortcomings. This should include losing federal aid if borrowers are not repaying their loans—even if they do not default. Loan performance should also be tracked for at least five years instead of three.

The federal government, states, and institutions also need to make significant investments in college affordability to reduce the number of students who need a loan in the first place. Too many borrowers and defaulters are low-income students, the very people who would receive only grant aid under a rational system for college financing. Forcing these students to borrow has turned one of America’s best investments in socioeconomic mobility—college—into a debt trap for far too many.

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

1. In paragraph 2, Miller says, “There’s what the federal government looks at to judge colleges, and then there’s the real story.” What does he mean by “the real story”?

2. Why, according to Miller, is the amount of student debt at “crisis level” (para. 5)?

3. What early warning signs concerning student debt does the federal government overlook? Why is this a problem?

4. How do colleges avoid accountability? Why do you think for-profit colleges have “particularly awful results” (10)?

5. Why, according to Miller, is the current student-loan program unfair to low-income students?

6. Has Miller defined the problem he is addressing in enough detail? Explain.

7. How does Miller propose to solve the burgeoning student-loan problem? Are his suggestions reasonable? Do they seem feasible?

A STRIKE AGAINST STUDENT DEBT

ASTRA TAYLOR

Taylor’s op-ed appeared on February 27, 2015, in the New York Times.

This week a group of former students calling themselves the Corinthian 15 announced that they were committing a new kind of civil disobedience: a debt strike. They are refusing to make any more payments on their federal student loans.

Along with many others, they found themselves in significant debt after attending programs at the Corinthian Colleges, a collapsed chain of for-profit schools that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has accused of running a “predatory lending scheme.” While the bureau has announced a plan to reduce some of the students’ private loan debts, the strikers are demanding that the Department of Education use its authority to discharge their federal loans as well.

These 15 students are members of the Debt Collective, an organization that evolved out of a project I helped start in 2012 called the Rolling Jubilee. Until now, we have worked in the secondary debt market, using crowdfunded donations to buy portfolios of medical and educational debts for pennies on the dollar, just as debt collectors do.

Only, instead of collecting on them, we abolish them, operating under the belief that people shouldn’t go into debt for getting sick or going to school. This week, we erased $13 million of “unpaid tuition receivables” belonging to 9,438 people associated with Everest College, a Corinthian subsidiary.

But this approach has its limits. Federal loans, for example, are guaranteed by the government, and debtors can be freed of them—via bankruptcy—only under exceedingly rare circumstances. That means they aren’t sold at steep discounts and remain out of our reach. What’s more, America’s mountain of student debt is too immense for the Jubilee to make a significant dent in it.

Real change will require more organized actions like those taken by the Corinthian 15.

“If anyone deserves debt relief—morally and legally—it’s these students.”

If anyone deserves debt relief—morally and legally—it’s these students. For-profit colleges are notorious for targeting low-income minorities, single mothers, and veterans with high-pressure, misleading recruitment techniques. The schools slurp up about a quarter of all federal student aid money, more than $30 billion a year, while their students run up a lifetime of debt for a degree arguably worth no more than a high school diploma.

But for-profit schools aren’t the only problem. Degrees earned from traditional colleges can also leave students unfairly burdened.

Today, a majority of outstanding student loans are in deferral, delinquency, or default. As state funding for education has plummeted, public colleges have raised tuition. Private university costs are skyrocketing, too, rising roughly 25 percent over the last decade. That’s why every class of graduates is more in the red than the last.

Modest fixes are not enough. Consider the interest rate tweaks or income-based repayment plans offered by the Obama administration. They lighten the debt burden on some—but not everyone qualifies. They do nothing to address the $165 billion private loan market, where interest rates are often the most punishing, or how higher education is financed.

Americans now owe $1.2 trillion in student debt, a number predicted by the think tank Demos to climb to $2 trillion by 2025. What if more people from all types of educational institutions and with all kinds of debts followed the example of the Corinthian 15, and strategically refused to pay back their loans? This would transform the debts into leverage to demand better terms, or even a better way of funding higher education altogether.

The quickest fix would be a full-scale student debt cancellation. For students at predatory colleges like Corinthian, this could be done immediately by the Department of Education. For the broader population of students, it would most likely take an act of Congress.

Student debt cancellation would mean forgone revenue in the near term, but in the long term it could be an economic stimulus worth much more than the immediate cost. Money not spent paying off loans would be spent elsewhere. In that situation, lenders, debt collectors, servicers, guaranty agencies, asset-backed security investors, and others who profit from student loans would suffer the most from debt forgiveness.

We also need to bring back the option of a public, tuition-free college education once represented by institutions like the University of California, which charged only token fees. By the Rolling Jubilee’s estimate, every public two- and four-year college and university in the United States could be made tuition-free by redirecting all current educational subsidies and tax exemptions straight to them and adding approximately $15 billion in annual spending.

This might sound like a lot, but it’s a small price to pay to restore America’s place on the long list of countries that provide tuition-free education.

To get there, more groups like the Corinthian 15 will have to show that they are willing to throw a wrench in the gears of the system by threatening to withhold payment on their debt. Everyone deserves a quality education. We need to come up with a better way to provide it than debt and default.

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

1. Taylor begins her essay by discussing the Corinthian 15. How does this focus help her introduce the problem she wants to solve?

2. Paraphrase Taylor’s thesis by filling in the following template.

o The Department of Education should solve the student debt crisis by .

3. What two problems does Taylor discuss? Does she describe them in enough detail? Explain.

4. What solutions does Taylor offer? How feasible are these solutions?

5. At what points in her essay does Taylor address objections to her proposal? Does she address the most important objections? If not, what other objections should she have addressed?

6. Taylor uses three terms that might be unfamiliar to some readers.

§ secondary debt market (para. 3)

§ crowdfunded donations (3)

§ unpaid tuition receivables (4)

§ Look up these terms, and then reread the paragraphs in which they appear. Do these terms help Taylor develop her argument, or could she have made her points without them?

7. What assumptions does Taylor assume are self-evident and need no proof? Do you agree? If not, what evidence should Taylor have included to support these assumptions?

DON’T BLAME THE GOVERNMENT

SAM ADOLPHSEN

This opinion piece was published online on May 1, 2012, at TheMaineWire.com.

I still remember the day.

I was sitting at my kitchen table, pen in hand, and I signed the dotted line to borrow a significant amount of money to pay for my first year of college.

The funny thing was, despite what you might hear in the media these days, no one was standing over my shoulder forcing me to. No government official told me I had to borrow the money. It was my decision then and it’s my debt today. I weighed the price of borrowing against the value of a secondary degree, and I chose education.

My decision, my responsibility.

That’s not what you are hearing today from most of America’s youth though. There are rallies in the streets of Portland, and in cities across America, with “Occupy” inspired students and graduates whining about their debt and how they need a way out. Students that have borrowed too much, of their own free will, for degrees that haven’t led to a job, are now demanding a handout.

My generation is looking for a bailout. It doesn’t matter that many of them are in tough positions, loaded with debt, because they made poor choices. It doesn’t matter that borrowing money is a personal decision and requires personal responsibility. They want the easy way out.

“They want the easy way out.”

Take the example of Stephanie, featured in a recent story from the Philadelphia Inquirer that re-ran in the Portland Press Herald. Stephanie, the story laments, owes over $100,000 in student loans. Poor Stephanie. Then we find out that, for one, Stephanie is in law school (really, becoming a lawyer costs money? Who knew . . .) and even worse, we find out that Stephanie, had a FREE RIDE to Rutgers, but instead chose to borrow money to go to a smaller private school because she “fell in love with it.”

So Stephanie didn’t have to take on student loan debt. She chose to. Why should I feel sorry for her? Why should the government lower her interest rates so taxpayers can help her pay those loans back? It’s her debt. Not the taxpayers of America.

Other decisions factor into this discussion as well. The Press Herald ran another story a couple days ago, highlighting several students who carried student loan debt. One of the students was a Social Worker who owes $97,000 in student loan debt. A cursory search of the internet will tell you that social workers don’t earn enough to warrant that kind of debt. The same goes for a Maine student who will owe more than $27,000 for his degree in Philosophy.

Seriously, I know Walt Disney told my generation we can “be whatever we want to be” if we “believe in ourselves” but borrowing $27,000 for a career in philosophy . . . in Maine? That’s a questionable decision at best, and it’s not the government’s fault.

The government already stepped in quietly and took over the student loan industry as part of Obamacare, and they already used taxpayer money to lower interest rates on current government student loans to 3.4 percent. Now those taxpayer subsidized interest rates are set to expire, and more than double, and the “gimme gimme” nation doesn’t like it.

Naturally, those who want government to take care of them are calling for the interest rates to be held at 3.4 percent, with the taxpayers chipping in for the difference. But make no mistake, even if those rates are held, this won’t be the end of the discussion. Now that the government holds all student loans, they have the opportunity to “bail out students” by forgiving loans. “Occupy” camps in a park near you are already chanting to the beat of the “forgive all student loans” drum, and you can expect that cry to get louder this summer. (It’s warm so they can start “occupying” again.)

Now don’t get me wrong. I agree that college costs are too high. And that IS partly government’s fault. Consider the University of Maine, piling on raises for their teachers, while simultaneously jacking up rates for students. In just a few years, university salaries were up 29 percent overall while at the same time tuition costs jumped 30 percent. That’s unacceptable and it’s a problem that needs to be addressed.

It’s also the government’s fault that anybody considers a bailout a legitimate solution to our problems. The bank bailouts and Obama’s absolute boondoggle “American Recovery Act” set the precedent and taught my generation that poor decisions and failure can be fixed with a government check. Shame on them for that, and shame on us for looking to government to bail out students now.

Ultimately, students and their parents make the decision to borrow money for school. And it’s their responsibility to pay it back. I’m tired of the whining, I’m tired of the blame game, and I’m tired of people relying on government to bail them out.

It’s your debt. Pay it yourself.

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

1. Adolphsen states his thesis in paragraph 4: “My decision, my responsibility.” In your own words, write an alternate one-sentence thesis statement for this essay on the lines below.

o Thesis Statement: .

o Is your thesis more or less effective than Adolphsen’s? Explain.

2. Adolphsen uses two examples to support his point that some people in his generation “want the easy way out” (para. 6). Are these examples enough to support his point? What other evidence could he have provided?

3. Could Adolphsen be accused of oversimplifying a complex issue? In other words, does he make hasty or sweeping generalizations? Does he beg the question? If so, where?

4. Where in his essay does Adolphsen concede a point to those who disagree with him? How effectively does he deal with this point?

5. How does Adolphsen characterize those who want student-debt relief? Are his characterizations fair? Accurate? Do these characterizations help or hurt his credibility? Explain.

6. In what sense is Adolphsen’s essay a refutation of Astra Taylor’s essay (p. 587)?

VISUAL ARGUMENT: STUDENT DEBT CRISIS SOLUTION

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

1. This image, which appeared at the beginning of this chapter, shows protesters rallying on April 25, 2012, the day that student loan debt reached $1 trillion. The 1T Day movement proposed that government should cover higher education costs, with any necessary loans to be granted without interest, and for debt forgiveness of past loans. How do the images in their protests connect to this proposal?

2. Is it easy to understand the group’s aims and solutions from their signs and props?

3. How do the images in the protest help support the argument and proposal being made by this group?

TEMPLATE FOR WRITING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

Write a one-paragraph proposal argument in which you consider the topic, “Should the Government Do More to Relieve the Student-Loan Burden?” Follow the template below, filling in the blanks to create your proposal.

The current federal student-loan program has some problems that must be addressed. For example, . In order to address this situation, . First, . Second,. Finally, . Not everyone agrees that this is the way to solve these problems, however. Some say . Others point out that . These objections make sense, but . All in all, .

![]()

EXERCISE 16.6 EXPANDING YOUR PROPOSAL

Ask several of your instructors and your classmates whether they think the government should do more to relieve the student-loan burden. Then, add their responses to the paragraph you wrote using the template above.

![]()

EXERCISE 16.7 WRITING A PROPOSAL

Write a proposal arguing that the government should do more to relieve the student-loan burden. Be sure to present examples from your own experience to support your arguments. (If you like, you may incorporate the material you developed for the template and for Exercise 16.7 into your essay.) Cite the readings on pages 578—592, and be sure to document your sources and include a works-cited page. (See Chapter 10 for information on documenting sources.)

![]()

EXERCISE 16.8 REVIEWING THE FOUR PILLARS OF ARGUMENT

Review the four pillars of argument discussed in Chapter 1. Does your essay include all four elements of an effective argument? Add anything that is missing.

![]() WRITING ASSIGNMENTS: PROPOSAL ARGUMENTS

WRITING ASSIGNMENTS: PROPOSAL ARGUMENTS

1. Each day, students at college cafeterias throw away hundreds of pounds of uneaten food. A number of colleges have found that by simply eliminating the use of trays, they can cut out much of this waste. At one college, for example, students who did not use trays wasted 14.4 percent less food for lunch and 47.1 percent less for dinner than those who did use trays. Write a proposal to your college or university in which you recommend eliminating trays from dining halls. Use your own experiences as well as information from your research and from interviews with other students to support your position. Be sure to address one or two arguments against your position.

2. Look around your campus, and find a service that you think should be improved. It could be the financial aid office, the student health services, or the writing center. Then, write an essay in which you identify the specific problem (or problems) and suggest a solution. If you wish, interview a few of your friends to get some information that you can use to support your proposal.

3. Assume that your college or university has just received a million-dollar donation from an anonymous benefactor. Your school has decided to solicit proposals from both students and faculty on ways to spend the money. Write a proposal to the president of your school in which you identify a good use for this windfall. Make sure you identify a problem, present a solution, and discuss the advantages of your proposal. If possible, address one or two arguments against your proposal—for example, that the money could be put to better use somewhere else.

Part 5 Review: Combining Argumentative Strategies

In Chapters 12—16, you have seen how argumentative essays can use different strategies to serve particular purposes. The discussions and examples in these chapters highlighted the use of a single strategy for a given essay. However, many (if not most) argumentative essays combine several different strategies.

For example, an argument recommending that the United States implement a national sales tax could be largely a proposal argument, but it could present a cause-and-effect argument to illustrate the likely benefits of the proposal, and it could also use an evaluation argument to demonstrate the relative advantages of this tax as compared to other kinds of taxes.

The following two essays—“RFK’s Still a Leadership Role Model for Youth” and “Fulfill George Washington’s Last Wish—a National University”—illustrate how various strategies can work together in a single argument. (The first essay includes marginal annotations that identify the different strategies the writer uses to advance his argument.)

RFK’S STILL A LEADERSHIP ROLE MODEL FOR YOUTH

ROBERT M. FRANKLIN

This article first appeared in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution on June 8, 2018.

At a moment when moral leadership is desperately needed in America and across the globe, we need to remember Bobby Kennedy and his style of moral leadership. Another American hero who was killed by a gun in 1968 at the age of 42, U.S. Senator Kennedy demonstrated the art of bringing diverse people together for the purpose of improving the nation, and he repeatedly expressed his great faith that young people and students would lead us to achieve a better world.

Proposal argument

Fifty years later, today’s students are mobilizing to make changes in gun laws, police behavior, respecting women, the environment, and many other social concerns. They need to take a page from the playbook of Bobby Kennedy.

For years, I have anticipated and dreaded the arrival of 2018, a perfectly ambivalent time zone of ecstasy and pain. We are here now, and far from being re-traumatized by painful memories, I am grateful for the lives of, and surprised by the abiding relevance of Bobby Kennedy and Martin King.

Ethical argument

In times of moral ambiguity and deep division, we need moral leaders who can bring us together and offer guidance, correction, and hope. That’s what Kennedy did on the night that Rev. King was murdered just two short months before his own assassination.

“In times of moral ambiguity and deep division, we need moral leaders who can bring us together and offer guidance, correction, and hope.”

I was a high school student in Chicago and felt crushed by the news of King’s death in Memphis. Searching for a way to make sense of the senseless theft of the life of another good man, on the radio I heard the soft and wavering but confident remarks of Robert F. Kennedy as he spoke impromptu to a crowd of people gathering in the streets of Indianapolis.

Kennedy did what moral leaders do. He started with empathy. He reminded people, especially African Americans angered by King’s murder that his own brother was also murdered, but this did not cause him to hate. His four-minute speech became King’s first eulogy as he said, “What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence or lawlessness; but love and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or they be black.”

In a haunting coincidence in 1966, almost two years to the day of his own assassination, Bobby spoke to members of the National Union of South African Students at the University of Cape Town as they mobilized to dismantle apartheid.

In 2006, my wife and I were in South Africa for the 40th anniversary of that speech and visited with the senator’s daughter, Rory Kennedy, after she delivered a speech to remember the occasion. We all celebrated his empathy and his truthfulness as he spoke of America’s freedom struggle and the courageous black and white students who were dismantling racism in America.

Ethical argument

Bobby said, “Each nation has different obstacles and different goals, shaped by the vagaries of history and of experience. Yet as I talk to young people around the world I am impressed not by the diversity but by the closeness of their goals, their desires and their concerns and their hope for the future.” Then he cited the many examples of social evil in the world that “reflect the imperfections of human justice” and reminded them that the youth today represent “the only true international community” as he applauded their willingness to make sacrifices on behalf of a better society.

Definition argument

I teach classes at Emory University that attempt to understand the principles and practices of moral leaders. We delve into their personal qualities or virtues, their ways of thinking about justice, and the outcomes they have. We believe that they have integrity, courage, and imagination for serving the common good while inviting others to join them. They have a knack for standing in places of suffering and conflict to offer words of hope, justice, and the possibility of reconciliation.

Evaluation argument