Practical argument: A text and anthology - Laurie G. Kirszner, Stephen R. Mandell 2019

Planning, drafting, and revising an argumentative essay

Writing an argumentative essay

AT ISSUE

Should All College Campuses Go Green?

In recent years, more and more American colleges and universities have become “green campuses,” emphasizing sustainability—the use of systems and materials that will not deplete the earth’s natural resources. Various schools have taken steps such as the following:

§ Placing an emphasis on recycling and reducing nonbiodegradable waste

§ Creating green buildings and using eco-friendly materials in construction projects

§ Instituting new curricula in environmental science

§ Monitoring their greenhouse gas emissions and evaluating their carbon footprint

§ Growing crops on campus to feed students

§ Hiring full-time “sustainability directors”

§ Encouraging students to use bikes instead of cars

§ Purchasing wind-generated electricity to supply the campus’s energy

§ Eliminating trays in college cafeterias

Although many schools continue to launch ambitious programs and projects to reduce their energy dependence, some have been more cautious, citing the high cost of such programs and the need to allocate resources elsewhere. Moreover, some critics of the green movement object to the notion that colleges should help to make students “sustainability literate.” Such critics consider the green movement to be an expression of political correctness that at best does no more than pay lip service to the problem and at worst threatens academic freedom by furthering a political agenda.

The question remains whether the green movement that is spreading rapidly across college campuses is here to stay or just a fad—or something between these two extremes. This chapter takes you through the process of writing an argumentative essay on the topic of whether all college campuses should go green. (Exercises guide you through the process of writing your own argumentative essay on a topic of your choice.)

Before you can write a convincing argumentative essay, you need to understand the writing process. You are probably already familiar with the basic outline of this process, which includes planning, drafting, and revising. This chapter reviews this familiar process and explains how it applies to the specific demands of writing an argumentative essay.

Choosing a Topic

The first step in planning an argumentative essay is to choose a topic you can write about. Your goal is to select a topic that you have some emotional stake in—not simply one that interests you. If you are going to spend hours planning, writing, and revising an essay, you should care about your topic. At the same time, you should be able to keep an open mind about your topic and be willing to consider various viewpoints. Your topic also should be narrow enough to fit the boundaries of your assignment—the time you have to work on the essay and its length and scope.

Typically, your instructor will give you a general assignment, such as the following.

Assignment

Write a three- to five-page argumentative essay on a topic related to college services, programs, facilities, or curricula.

The first thing you need to do is narrow this general assignment to a topic, focusing on one particular campus service, program, facility, or curriculum. You could choose to write about any number of topics—financial aid, the writing center, athletics, the general education curriculum—taking a position, for example, on who should receive financial aid, whether to expand the mission of the writing center, whether college athletes should receive a salary, or why general education requirements are important for business majors.

If you are interested in environmental issues, however, you might decide to write about the green movement that has been spreading across college campuses, perhaps using your observations of your own campus’s programs and policies to support your position.

Topic

The green movement on college campuses

Topics to Avoid

Certain kinds of topics are not appropriate for argumentative essays.

§ Topics that are statements of fact. Some topics are just not arguable. For example, you could not write an argumentative essay on a statement of fact, such as the fact that many colleges saw their endowments decline after the financial crisis of 2008. (A fact is not debatable, so there can be no argument.)

§ Topics that have been overused. Some familiar topics also present problems. These issues—the death penalty, abortion rights, and so on—are important (after all, that’s why they are written about so often), but finding an original argument on either side of the debate can be a challenge. For example, you might have a hard time finding something new to say that would convince some readers that the death penalty is immoral or that abortion is a woman’s right. In many people’s minds, these issues are “settled.” When you write on topics such as these, some readers’ strong religious or cultural beliefs are likely to prevent them from considering your arguments, however well supported they might be.

§ Topics that rely on subjective judgments. Some very narrow topics depend on subjective value judgment, often taking a stand on issues readers simply will not care much about, such as whether one particular video game or TV reality show is more entertaining than another. Such topics are unlikely to engage your audience (even if they seem compelling to you and your friends).

![]()

EXERCISE 7.1 CHOOSING A TOPIC

In response to the boxed assignment on the previous page, list ten topics that you could write about. Then, cross out any that do not meet the following criteria:

§ The topic interests you.

§ You know something about the topic.

§ You care about the topic.

§ You are able to keep an open mind about the topic.

§ The topic fits the boundaries of your assignment.

Now, decide on one topic to write an essay about.

Thinking about Your Topic

Before you can start to develop a thesis statement or plan the structure of your argument, you need to think a bit about the topic you have chosen. You can use invention strategies—such as freewriting (writing without stopping for a predetermined time), brainstorming (making quick notes on your topic), or clustering (creating a diagram to map out your thoughts)—to help you discover ideas you might write about. You can also explore ideas in a writing journal or in conversations with friends, classmates, family members, or instructors.

Freewriting

People say green is good, but I’m not sure why. Do we really need a separate, smelly container for composting? Won’t the food decompose just as fast in a landfill? In middle school, we learned about the “three Rs” to save the environment—one was Recycle, but I forget the other two. Renew? Reuse? Remember? Whatever. OK, I know not to throw trash on the ground, and I know we’re supposed to separate trash and recycling, etc. I get that. But does all this time and effort really do any good?

Brainstorming

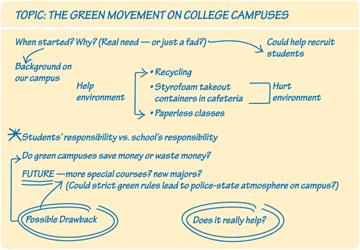

The text reads as follows.

Topic: The Green Movement on College Campuses

When started? Why? (Real need — or just a fad?) [An arrow from ’When started?’ points to a note that reads, Background on our campus. Another arrow from ’Real need — or just a fad?’ points to a note that reads, Could help recruit students.

Three points under ’Help environment’ reads as follows.

[Bullet point] Recycling.

[Bullet point] Styrofoam takeout containers in cafeteria. [Margin note to this point reads, Hurt environment]

[Bullet point] Paperless classes

[Asterisk] Students’ responsibility vs. school’s responsibility

Do green campuses save money or waste money? [Margin note reads, Possible drawback.]

Future — more special courses? new majors? [Margin note reads, Possible drawback.]

(Could strict green rules lead to police-state atmosphere on campus?)

[Margin note reads, Does it really help?]

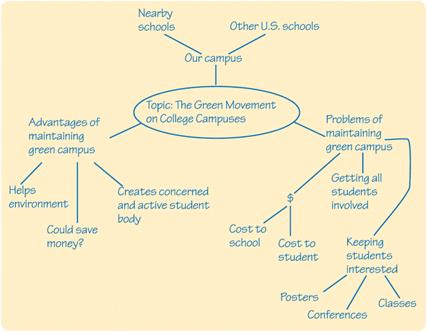

Clustering

Our campus considers Nearby schools and Other U. S. schools. An arrow joins ’Our campus’ to ’Topic: The Green Movement on College Campuses.’ Two branches from the topic reads, ’Advantages of maintaining green campus’ and ’Problems of maintaining green campus.’ Three points under ’Advantages of maintaining green campus’ are as follows: Helps environment, Could save money? and Creates concerned and active student body.

Three points under ’Problems of maintaining green campus’ are as follows: A dollar sign (further subdivided into Cost to school and Cost to student), Getting all students involved, and Keeping students interested (further subdivided into Posters, Conferences, and Classes).

When you finish exploring ideas, you should be able to construct a quick informal outline that lists the ideas you plan to discuss.

Informal Outline

· Topic: The Green Movement on College Campuses

o History/background

§ National

§ Our campus

o Positive aspects

§ Helps environment

§ Attracts new students

§ Negative aspects

o Cost

§ Enforcement

§ Future

By grouping your ideas and arranging them in a logical order, an informal outline like the preceding one can help lead you to a thesis statement that expresses the position you will take on the issue.

![]()

EXERCISE 7.2 EXPLORING IDEAS

Focusing on the topic you chose in Exercise 7.1, freewrite to explore ideas you might write about in your essay. Then, brainstorm to discover ideas. Finally, draw a cluster diagram to help you further explore possible ideas to write about.

![]()

EXERCISE 7.3 CONSTRUCTING AN INFORMAL OUTLINE

Construct an informal outline for an essay on the topic you chose in Exercise 7.1.

Drafting a Thesis Statement

After you have decided on a topic and thought about how you want to approach it, your next step is to take a stand on the issue you are going to discuss. You do this by expressing your position as a thesis statement.

A thesis statement is the central element of any argumentative essay. It tells readers what your position is and perhaps also indicates why you are taking this position and how you plan to support it. As you draft your thesis statement, keep the following guidelines in mind:

§ An argumentative thesis statement is not simply a statement of your topic; rather, it expresses the point you will make about your topic.

TOPIC

The green movement on college campuses

THESIS STATEMENT

College campuses should go green.

§ An argumentative thesis statement should be specific, clearly indicating to readers exactly what position you will take in your essay.

TOO GENERAL

Colleges need to do more to get students involved in environmental issues.

REVISED

Colleges should institute programs and classes to show students the importance of using sustainable resources.

§ An argumentative thesis statement should get right to the point, avoiding wordy, repetitive language.

WORDY

Because issues that revolve around the environment are so crucial and important, colleges should do more to increase student involvement in campus projects that are concerned with sustainability.

REVISED

Because environmental issues are so important, colleges should take steps to involve students in campus sustainability projects.

§ Many argumentative thesis statements include words such as should and should not.

§ College campuses should .

§ Because , colleges should .

§ Even though , colleges should not .

NOTE

At this point, any thesis that you come up with is tentative. As you think about your topic and perhaps read about it, you will very likely modify your thesis statement, perhaps expanding or narrowing its scope, rewording it to make it more precise, or even changing your position. Still, the thesis statement that you decide on at this point can give you some focus as you explore your topic.

TENTATIVE THESIS STATEMENT

College campuses should go green.

![]()

EXERCISE 7.4 DEVELOPING A THESIS STATEMENT

List five possible thesis statements for the topic you chose in Exercise 7.1. (To help you see your topic in several different ways, you might experiment by drafting at least one thesis statement that evaluates, one that considers causes and/or effects, and one that proposes a solution to a problem.) Which thesis statement seems to suggest the most promising direction for your essay? Why?

Understanding Your Purpose and Audience

When you write an argument, your primary purpose is to convince your audience to accept your position. Sometimes you will have other goals as well. For example, you might want to change readers’ ideas about an issue, perhaps by challenging a commonly held assumption. You might even want to move readers to take some action in support of your position.

To make the best possible case to your audience, you need to understand who your audience is—what knowledge, values, beliefs, and opinions your readers might have. You will also need to have some idea whether your audience is likely to be receptive, hostile, or neutral to the ideas you propose.

In most cases, it makes sense to assume that your readers are receptive but skeptical—that they have open minds but still need to be convinced. However, if you are writing about a topic that is very controversial, you will need to assume that at least some of your readers will not support your position and may, in fact, be hostile to it. If this is the case, they will be scrutinizing your arguments very carefully, looking for opportunities to argue against them. Your goal in this situation is not necessarily to win readers over but to make them more receptive to your position—or at least to get them to admit that you have made a good case even though they may disagree with you. At the same time, you also have to work to convince those who probably agree with you or those who are neutral (perhaps because the issue you are discussing is something they haven’t thought much about).

An audience of first-year college students who are used to the idea that sound environmental practices make sense might find the idea of a green campus appealing—and, in fact, natural and obvious. An audience of faculty or older students might be more skeptical, realizing that the benefits of green practices might be offset by the time and expense they could involve. College administrators might find the long-term goal of a green campus attractive (and see it as a strong recruitment tool), but they might also be somewhat hostile to your position, anticipating the considerable expense that would be involved. If you wrote an argument on the topic of green campuses, you would need to consider these positions—and, if possible, address them.

![]()

EXERCISE 7.5 CONSIDERING YOUR AUDIENCE

Consider how different audiences might respond to the thesis statement you found the most promising in Exercise 7.3. Identify five possible groups of readers on your college campus—for example, athletes, history majors, or part-time faculty. Would you expect each group to be receptive, hostile, or neutral to your position? Why?

Gathering Evidence

After you have a sense of who your audience will be and how these readers might react to your thesis, you can begin to collect evidence to support your thesis. As you look for evidence, you need to evaluate the usefulness and relevance of each of your sources, and you need to be alert for possible bias.

Evaluating the Evidence in Your Sources

As you read each potential source, consider the quality of the supporting evidence that the writer marshals to support his or her position. The more compelling the evidence, the more willing you should be to accept the writer’s ideas—and, perhaps, to integrate these ideas into your own essay.

NOTE

Don’t forget that if you use any of your sources’ ideas, you must document them. See Chapter 10 for information on MLA documentation format and Appendix B for information on APA documentation format.

To be convincing, the evidence that is presented in the sources you review should be accurate, relevant, representative, and sufficient:

§ Accurate evidence comes from reliable sources that are quoted carefully—and not misrepresented by being quoted out of context.

§ Relevant evidence applies specifically (not just tangentially) to the topic under discussion.

§ Representative evidence is drawn from a fair range of sources, not just those that support the writer’s position.

§ Sufficient evidence is enough facts, statistics, expert opinion, and so on to support the essay’s thesis.

(For more detailed information on evaluating sources, see Chapter 8.)

NOTE

Remember, the evidence you use to support your own arguments should also satisfy the four criteria listed above.

Detecting Bias in Your Sources

As you select sources, you should be alert for bias—a writer’s use of preconceived ideas (rather than factual evidence) as support for his or her arguments. A writer who demonstrates bias may not be trustworthy, and you should approach such a writer’s arguments with skepticism. To determine whether a writer is biased, follow these guidelines:

§ Consider what a writer explicitly tells you about his or her beliefs or opinions. For example, if a writer mentions that he or she is a lifelong member of the Sierra Club, a vegan, and the owner of a house heated by solar energy, then you should consider the possibility that he or she might downplay (or even disregard) valid arguments against maintaining a green campus rather than presenting a balanced view.

§ Look for slanted language. For example, a writer who mocks supporters of environmental issues as “politically correct” or uses pejorative terms such as hippies for environmentalists should not earn your trust.

§ Consider the supporting evidence the writer chooses. Does the writer present only examples that support his or her position and ignore valid opposing arguments? Does the writer quote only those experts who agree with his or her position—for example, only pro- (or only anti-) environmental writers? A writer who does this is presenting an unbalanced (and therefore biased) case.

§ Consider the writer’s tone. A writer whose tone is angry, bitter, or sarcastic should be suspect.

§ Consider any overtly offensive statements or characterizations that a writer makes. A writer who makes negative assumptions about college students (for example, characterizing them as selfish and self-involved and therefore dismissing their commitment to campus environmental projects) should be viewed with skepticism.

NOTE

As you develop your essay, be alert for any biases you hold that might affect the strength or logic of your own arguments. See “Being Fair,” page 267.

![]()

EXERCISE 7.6 EXAMINING YOUR BIASES

In writing an essay that supports the thesis statement you have been working with in this chapter, you might find it difficult to remain objective. What biases do you have that you might have to watch for as you research and write about your topic?

![]()

EXERCISE 7.7 GATHERING EVIDENCE

Now, gather evidence to support the thesis statement you decided on in Exercise 7.3, evaluating each source carefully (and consulting Chapter 8 as necessary). Be on the lookout for bias in your sources.

USING VISUALS AS EVIDENCE

As you draft your essay, you might want to consider adding a visual—such as a chart, graph, table, photo, or diagram—to help you make a point more forcefully. For example, in a paper on the green campus movement, you could include anything from photos of students recycling to a chart comparing energy use at different schools. Sometimes a visual can be so specific, so attractive, or so dramatic that its impact will be greater than words would be; in such cases, the image itself can constitute a visual argument. At other times, a visual can expand and support a written argument.

You can create a visual yourself, or you can download one from the internet, beginning your search with Google Images. If you download a visual and paste it into your paper, be sure to include a reference to the visual in your discussion to explain the argument it makes—or to show readers how it supports your argument.

NOTE

Don’t forget to label any visuals with a figure number, to use proper documentation, and to include a caption explaining what the visual shows, as the student essay that begins on page 278 does. (For information on documentation, see Chapter 10.)

Refuting Opposing Arguments

As you plan your essay and explore sources that might supply your supporting evidence, you will encounter evidence that contradicts your position. You may be tempted to ignore this evidence, but if you do, your argument will not be very convincing. Instead, as you review your sources, identify the most convincing arguments against your position and prepare yourself to refute them (that is, to disprove them or call them into question), showing them to be illogical, unfair, or untrue. Indicating to readers that you are willing to address these arguments—and that you can respond effectively to them—will help convince them to accept your position.

Of course, simply saying that your opponent’s position is “wrong” or “stupid” is not convincing. You need to summarize opposing arguments accurately and clearly identify their weaknesses. In the case of a strong opposing argument, be sure to concede its strengths (that is, acknowledge that it is a valid position) before you refute it; if you do not, readers may see you as uninformed or unfair. For example, you could refute the argument that maintaining a green campus is too expensive by acknowledging that although expenditures are high at first, in the long run, a green campus is not all that costly considering its benefits.

In assessing the strength of an opposing argument, you should always try to identify its limitations. Even a strong opposing argument may be addressing only one part of the problem. For example, an argument might focus on students’ reluctance to comply with campus environmental guidelines and ignore efforts by the school’s administration to overcome that reluctance. Or, an argument might focus on the current lack of green buildings on campus and ignore the school’s requirement that green materials be used in all campus construction projects.

Also be careful not to create a straw man—that is, do not distort an opposing argument by oversimplifying it so it can be easily refuted (for example, claiming that environmentalists believe that sustainability should always be a college’s first priority in its decisions about allocating resources). This unfair tactic will discourage readers from trusting you and thus will undermine your credibility.

Strategies for Refuting Opposing Arguments

In order to do a convincing job of refuting an argument that challenges your position, you need to consider where such an argument might be weak and on what basis you could refute it.

WEAKNESS IN OPPOSING ARGUMENT |

REFUTATION STRATEGY |

Factual errors or contrary-to-fact statements |

Identify and correct the errors, perhaps explaining how they call the writer’s credibility into question. |

Insufficient support |

Point out that more facts and examples are needed; note the kind of support (for example, statistics) that is missing. |

Illogical reasoning |

Identify fallacies in the writer’s argument, and explain why the logic is flawed. For example, is the writer setting up a straw man or employing the either/or fallacy? (See Chapter 5 for more on logic.) |

Exaggerated or overstated claims |

Identify exaggerated statements, and explain why they overstate the case. |

Biased statements |

Identify biased statements, and show how they exhibit the writer’s bias. (See page 259, “Detecting Bias in Your Sources.”) |

Irrelevant arguments |

Identify irrelevant points and explain why they are not pertinent to the writer’s argument. |

![]()

EXERCISE 7.8 EVALUATING OPPOSING ARGUMENTS

Read paragraphs 7 and 8 of the student essay on page 278. Summarize the opposing argument presented in each of these paragraphs. Then, consulting the preceding list, identify the specific weakness of each opposing argument. Finally, explain the strategy the student writer uses to refute the argument.

Revising Your Thesis Statement

Before you can begin to draft your argumentative essay, and even before you can start to arrange your ideas, you need to revise your tentative thesis statement so it says exactly what you want it to say. After you have gathered and evaluated evidence to support your position and considered the merits of opposing ideas, you are ready to refocus your thesis and state it in more precise terms. Although a tentative thesis statement such as “College campuses should go green” is a good start, the thesis that guides your essay’s structure should be more specific. In fact, it will be most useful as a guide if its phrasing actually acknowledges opposing arguments.

REVISED THESIS STATEMENT

Colleges should make every effort to create and sustain green campuses because by doing so they will not only improve their own educational environment but also ensure their institutions’ survival and help solve the global climate crisis.

![]()

EXERCISE 7.9 REVISING YOUR THESIS STATEMENT

Consulting the sources you gathered in Exercise 7.7, list all the arguments against the position you express in your thesis statement. Then, list possible refutations of each of these arguments. When you have finished, revise your thesis statement so that it is more specific, acknowledging the most important argument against your position.

After you have revised your thesis statement, you will have a concise blueprint for the essay you are going to write. At this point, you will be ready to plan your essay’s structure and write a first draft.

Structuring Your Essay

As you learned in Chapter 1, an argumentative essay, like other essays, includes an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. In the introduction of an argumentative essay, you state your thesis; in the body paragraphs, you present evidence to support your thesis and you acknowledge and refute opposing arguments; and in your conclusion, you bring your argument to a close and reinforce your thesis with a strong concluding statement. As you have seen, these four elements—thesis, evidence, refutation, and concluding statement—are like the four pillars of the ancient Greek temple, supporting your argument so that it will stand up to scrutiny.

SUPPLYING BACKGROUND INFORMATION

Depending on what you think your readers know—and what you think they need to know—you might decide to include a background paragraph that supplies information about the issue you are discussing. For example, in an essay about green campuses, you might briefly sum up the history of the U.S. environmental movement and trace its rise on college campuses. If you decide to include a background paragraph, it should be placed right after your introduction, where it can prepare readers for the discussion to follow.

Understanding basic essay structure can help you as you shape your essay. You should also know how to use induction and deduction, how to identify a strategy for your argument, and how to construct a formal outline.

Using Induction and Deduction

Many argumentative essays are structured either inductively or deductively. (See Chapter 5 for explanations of induction and deduction.) For example, the body of an essay with the thesis statement that is shown on page 263 could have either of the following two general structures:

INDUCTIVE STRUCTURE

§ Colleges have been taking a number of steps to follow green practices.

§ Through these efforts, campuses have become more environmentally responsible, and their programs and practices have had a positive impact on the environment.

§ Because these efforts are helping to save the planet, they should be expanded.

DEDUCTIVE STRUCTURE

§ Saving the planet is vital.

§ Green campuses are helping to save the planet.

§ Therefore, colleges should continue to develop green campuses.

These structures offer two options for arranging material in your essay. Many argumentative essays, however, combine induction and deduction or use other strategies to organize their ideas.

Identifying a Strategy for Your Argument

There are a variety of different ways to structure an argument, and the strategy you use depends on what you want your argument to accomplish. In this text, we discuss five options for presenting material: definition arguments, cause-and-effect arguments, evaluation arguments, ethical arguments, and proposal arguments. (See p. 390 for more on these options.)

Any of the five options listed above could guide you as you develop an essay on green campuses:

§ You could structure your essay as a definition argument, explaining the concept of a green campus and giving examples to show its positive (or negative) impact.

§ You could structure your essay as a cause-and-effect argument, showing how establishing a green campus can have positive results for students and for the campus—or how it might cause problems.

§ You could structure your essay as an evaluation argument, assessing the strengths and weaknesses of various programs and policies designed to create and sustain a green campus.

§ You could structure your essay as an ethical argument, explaining why maintaining a green campus is the right thing to do from a moral or ethical standpoint.

§ You could structure your essay as a proposal argument, recommending a particular program, service, or course of action and showing how it can support a green campus.

Constructing a Formal Outline

If you like, you can construct a formal outline before you begin your draft. (Later on, you might also construct an outline of your finished paper to check the logic of its structure.) A formal outline, which is more detailed and more logically organized than the informal outline shown on page 255, presents your main points and supporting details in the order in which you will discuss them.

A formal outline of the first body paragraph (para. 2) of the student essay on page 278 would look like this:

I. Background of the term green

A. 1960s environmental movement

1. Political agenda

2. Environmental agenda

B. Today’s movements

1. Eco-friendly practices

2. Green values

Following a formal outline makes the drafting process flow smoothly, but many writers find it hard to predict exactly what details they will use for support or how they will develop their arguments. In fact, your first draft is likely to move away from your outline as you develop your ideas. Still, if you are the kind of writer who prefers to know where you are going before you start on your way, you will probably consider the time you devote to outlining to be time well spent.

![]()

EXERCISE 7.10 CONSTRUCTING A FORMAL OUTLINE

Look back at the thesis you decided on earlier in this chapter, and review the evidence you collected to support it. Then, construct a formal outline for your argumentative essay.

Establishing Credibility

Before you begin drafting your essay, you need to think about how to approach your topic and your audience. The essay you write will use a combination of logical, emotional, and ethical appeals, and you will have to be careful to use these appeals reasonably. (See pp. 15—21 for information on these appeals.) As you write, you will concentrate on establishing yourself as well informed, reasonable, and fair.

Being Well Informed

If you expect your readers to accept your ideas, you will need to establish yourself as someone they should believe and trust. Achieving this goal depends upon showing your audience that you have a good command of your material—that is, that you know what you are talking about.

If you want readers to listen to what you are saying, you need to earn their respect by showing them that you have done your research, that you have collected evidence that supports your argument, and that you understand the most compelling arguments against your position. For example, discussing your own experiences as a member of a campus or community environmental group, your observations at a Greenpeace convention, and essays and editorials that you have read on both sides of the issue will encourage your audience to accept your ideas on the subject of green campuses.

Being Reasonable

Even if your evidence is strong, your argument will not be convincing if it does not seem reasonable. One way to present yourself as a reasonable person is to establish common ground with your readers, stressing possible points of agreement instead of attacking those who might disagree with your position. For example, saying, “We all want our planet to survive” is a more effective strategy than saying, “Those who do not support the concept of a green campus are out to destroy our planet.” (For more on establishing common ground, see the discussion of Rogerian argument in Chapter 6.)

Another way to present yourself as a reasonable person is to maintain a reasonable tone. Try to avoid absolutes (words like always and never); instead, use more conciliatory language (in many cases, much of the time, and so on). Try not to use words and phrases like obviously or as anyone can see to introduce points whose strength may be obvious only to you. Do not brand opponents of your position as misguided, uninformed, or deluded; remember, some of your readers may hold opposing positions and will not appreciate your unfavorable portrayal of them.

Finally, be very careful to treat your readers with respect, addressing them as your intellectual equals. Avoid statements that might insult them or their beliefs (“Although some ignorant or misguided people may still think . . .”). And never assume that your readers know less about your topic than you do; they may actually know a good deal more.

Being Fair

If you want readers to respect your point of view, you need to demonstrate respect for them by being fair. It is not enough to support your ideas convincingly and maintain a reasonable tone. You also need to avoid unfair tactics in your argument and take care to avoid bias.

In particular, you should be careful not to distort evidence, quote out of context, slant evidence, make unfair appeals, or use logical fallacies. These unfair tactics may influence some readers in the short term, but in the long run such tactics will alienate your audience.

§ Do not distort evidence. Distorting (or misrepresenting) evidence is an unfair tactic. It is not ethical or fair, for example, to present your opponent’s views inaccurately or to exaggerate his or her position and then argue against it. If you want to argue that expanding green programs on college campuses are a good idea, it is not fair to attack someone who expresses reservations about their cost by writing, “Mr. McNamara’s concerns about cost reveal that he has basic doubts about saving the planet.” (His concerns reveal no such thing.) It is, however, fair to acknowledge your opponent’s reasonable concerns about cost and then go on to argue that the long-term benefits of such programs justify their expense.

§ Do not quote out of context. It is perfectly fair to challenge someone’s stated position. It is not fair, however, to misrepresent that position by quoting out of context—that is, by taking the words out of the original setting in which they appeared. For example, if a college dean says, “For schools with limited resources, it may be more important to allocate resources to academic programs than to environmental projects,” you are quoting the dean’s remarks out of context if you say, “According to Dean Levering, it is ’more important to allocate resources to academic programs than to environmental projects.’ ”

§ Do not slant evidence. An argument based on slanted evidence is not fair. Slanting involves choosing only evidence that supports your position and ignoring evidence that challenges it. This tactic makes your position seem stronger than it actually is. Another kind of slanting involves using biased language to unfairly characterize your opponents or their positions—for example, using a dismissive term such as tree hugger to describe a concerned environmentalist.

§ Do not make unfair appeals. If you want your readers to accept your ideas, you need to avoid unfair appeals to the emotions, such as appeals to your audience’s fears or prejudices. For example, if you try to convince readers of the importance of using green building materials by saying, “Construction projects that do not use green materials doom future generations to a planet that cannot sustain itself,” you are likely to push neutral (or even receptive) readers to skepticism or to outright hostility.

§ Do not use logical fallacies. Using logical fallacies (flawed arguments) in your writing is likely to diminish your credibility and alienate your readers. (See Chapter 5 for information about logical fallacies.)

MAINTAINING YOUR CREDIBILITY

Be careful to avoid phrases that undercut your credibility (“Although this is not a subject I know much about”) and to avoid apologies (“This is just my opinion”). Be as clear, direct, and forceful as you can, showing readers you are confident as well as knowledgeable. And, of course, be sure to proofread carefully: grammatical and mechanical errors and typos will weaken your credibility.

Drafting Your Essay

Once you understand how to approach your topic and your audience, you will be ready to draft your essay. At this point, you will have selected the sources you will use to support your position as well as identified the strongest arguments against your position (and decided how to refute them). You may also have prepared a formal outline (or perhaps just a list of points to follow).

As you draft your argumentative essay, keep the following guidelines in mind:

§ Follow the general structure of an argumentative essay. State your thesis in your first paragraph, and discuss each major point in a separate paragraph, moving from least to most important point to emphasize your strongest argument. Introduce each body paragraph with a clearly worded topic sentence. Discuss each opposing argument in a separate paragraph, and be sure your refutation appears directly after your mention of each opposing argument. Finally, don’t forget to include a strong concluding statement in your essay’s last paragraph.

§ Decide how to arrange your material. As you draft your essay, you may notice that it is turning out to be an ethical argument, an evaluation argument, or another kind of argument that you recognize. If this is the case, you might want to ask your instructor how you can arrange your material so it is consistent with this type of argument (or consult the relevant chapter in Part 5, “Strategies for Argument”).

§ Use evidence effectively. As you make your points, select the evidence that supports your argument most convincingly. As you write, summarize or paraphrase relevant information from your sources, and respond to this information in your own voice, supplementing material that you find in your sources with your own original ideas and conclusions. (For information on finding and evaluating sources, see Chapter 8; for information on integrating source material, see Chapter 9.)

§ Use coordination and subordination to make your meaning clear. Readers shouldn’t have to guess how two points are connected; you should use coordination and subordination to show them the relationship between ideas.

Choose coordinating conjunctions—and, but, or, nor, for, so, and yet—carefully, making sure you are using the right word for your purpose. (Use and to show addition; but, for, or yet to show contradiction; or to present alternatives; and so to indicate a causal relationship.)

Choose subordinating conjunctions—although, because, and so on—carefully, and place them so that your emphasis will be clear.

Consider the two ideas expressed in the following sentences.

Achieving a green campus is vitally important. Creating a green campus is expensive.

If you want to stress the idea that green measures are called for, you would connect the sentences like this:

Although creating a green campus is expensive, achieving a green campus is vitally important.

If, however, you want to place emphasis on the high cost, you would connect the sentences as follows:

Although achieving a green campus is vitally important, creating a green campus is expensive.

§ Include transitional words and phrases. Be sure you have enough transitions to guide your readers through your discussion. Supply signals that move readers smoothly from sentence to sentence and paragraph to paragraph, and choose signals that make sense in the context of your discussion.

SUGGESTED TRANSITIONS FOR ARGUMENT

§ To show causal relationships: because, as a result, for this reason

§ To indicate sequence: first, second, third; then; next; finally

§ To introduce additional points: also, another, in addition, furthermore, moreover

§ To move from general to specific: for example, for instance, in short, in other words

§ To identify an opposing argument: however, although, even though, despite

§ To grant the validity of an opposing argument: certainly, admittedly, granted, of course

§ To introduce a refutation: however, nevertheless, nonetheless, still

§ Define your terms. If the key terms of your argument have multiple meanings—as green does—be sure to indicate what the term means in the context of your argument. Terms like environmentally friendly, climate change, environmentally responsible, sustainable, and sustainability literacy may mean very different things to different readers.

§ Use clear language. An argument is no place for vague language or wordy phrasing. If you want readers to understand your points, your writing should be clear and direct. Avoid vague words like good, bad, right, and wrong, which are really just unsupported judgments that do nothing to help you make your case. Also avoid wordy phrases such as revolves around and is concerned with, particularly in your thesis statement and topic sentences.

§ Finally, show your confidence and your mastery of your material. Avoid qualifying your statements with phrases such as I think, I believe, it seems to me, and in my opinion. These qualifiers weaken your argument by suggesting that you are unsure of your material or that the statements that follow may not be true.

GRAMMAR IN CONTEXT

Using Parallelism

As you draft your argumentative essay, you should express corresponding words, phrases, and clauses in parallel terms. The use of matching parts of speech to express corresponding ideas strengthens your argument’s impact because it enables readers to follow your line of thought.

In particular, use parallelism in sentences that highlight paired items or items in a series.

§ Paired Items

UNCLEAR

Maintaining a green campus is important because it sets an example for students and the environment will be protected.

PARALLEL

Maintaining a green campus is important because it sets an example for students and protects the environment.

§ Items in a Series

UNCLEAR

Students can do their part to support green campus initiatives in four ways—by avoiding bottled water, use of electricity should be limited, and they can recycle packaging and also educating themselves about environmental issues is a good strategy.

PARALLEL

Students can do their part to support green campus initiatives in four ways—by avoiding bottled water, by limiting use of electricity, by recycling packaging, and by educating themselves about environmental issues.

![]()

EXERCISE 7.11 DRAFTING YOUR ARGUMENTATIVE ESSAY

Keeping the preceding guidelines in mind, write a draft of an argumentative essay that develops the thesis statement you have been working with. If you like, include a visual to support your argument.

Revising Your Essay

After you have written a draft of your essay, you will need to revise it. Revision is “re-seeing”—looking carefully and critically at the draft you have written. Revision is different from editing and proofreading, which focus on grammar, punctuation, mechanics, and the like. In fact, revision can involve substantial reworking of your essay’s structure and content. The strategies discussed on the pages that follow can help you revise your arguments.

Asking Questions

Asking some basic questions, such as those in the three checklists that follow, can help you to focus on the individual elements of your essay as you revise.

CHECKLIST

Questions about Your Essay’s Purpose and Audience

· What was your primary purpose in writing this essay? What other purposes did you have?

· What appeals, strategies, and evidence did you use to accomplish your goals?

· Who is the audience for your essay? Do you see your readers as receptive, hostile, or neutral to your position?

· What basic knowledge do you think your readers have about your topic? Have you provided enough background for them?

· What biases do you think your readers have? Have you addressed these biases in your essay?

· What do you think your readers believed about your topic before reading your essay?

· What do you want readers to believe now that they have read your essay?

CHECKLIST

Questions about Your Essay’s Structure and Style

· Does your essay have a clearly stated thesis?

· Are your topic sentences clear and concise?

· Have you provided all necessary background and definitions?

· Have you refuted opposing arguments effectively?

· Have you included enough transitional words and phrases to guide readers smoothly through your discussion?

· Have you avoided vague language and wordy phrasing?

· Does your essay have a strong concluding statement?

CHECKLIST

Questions about Your Essay’s Supporting Evidence

· Have you supported your opinions with evidence—facts, observations, examples, statistics, expert opinion, and so on?

· Have you included enough evidence to support your thesis?

· Do the sources you rely on present information accurately and without bias?

· Are your sources’ discussions directly relevant to your topic?

· Have you consulted sources that represent a wide range of viewpoints, including sources that challenge your position?

· Have you included one or more visuals to support your argument?

The answers to the questions in the checklists may lead you to revise your essay’s content, structure, and style. For example, you may want to look for additional sources that can provide the kind of supporting evidence you need, or you may want to add visuals or replace a visual with one that more effectively supports your argument. Then, you may notice you need to revise the structure of your essay, perhaps rearranging your points so that the most important point is placed last, for emphasis. You may also want to revise your essay’s introduction and conclusion, sharpening your thesis statement or adding a stronger concluding statement. Finally, you may decide to add more background material to help your readers understand the issue you are writing about or to help them take a more favorable view of your position.

Using Outlines and Templates

To check the logic of your essay’s structure, you can prepare a revision outline or consult a template.

§ To make sure your essay’s key points are arranged logically and supported convincingly, you can construct a formal outline of your draft. (See pp. 265—66 for information on formal outlines.) This outline will indicate whether you need to discuss any additional points, add supporting evidence, or refute an opposing argument more fully. It will also show you if paragraphs are arranged in a logical order.

§ To make sure your argument flows smoothly from thesis statement to evidence to refutation of opposing arguments to concluding statement, you can refer to one of the paragraph templates that appear throughout this book. These templates can help you to construct a one-paragraph summary of your essay.

Getting Feedback

After you have done as much as you can on your own, it is time to get feedback from your instructor and (with your instructor’s permission) from your school’s writing center or from other students in your class.

Instructor Feedback

You can get feedback from your instructor in a variety of different ways. For example, your instructor may ask you to email a draft of your paper to him or her with some specific questions (“Do I need paragraph 3, or do I have enough evidence without it?” “Does my thesis statement need to be more specific?”). The instructor will then reply with corrections and recommendations. If your instructor prefers a traditional face-to-face conference, you may still want to email your draft ahead of time to give him or her a chance to read it before your meeting.

Writing Center Feedback

You can also get feedback from a writing center tutor, who can be either a student or a professional. The tutor can give you another point of view about your paper’s content and organization and also help you focus on specific questions of style, grammar, punctuation, and mechanics. (Keep in mind, however, that a tutor will not edit or proofread your paper for you; that is your job.)

Peer Review

Finally, you can get feedback from your classmates. Peer review can be an informal process in which you ask a classmate for advice, or it can be a more structured process, involving small groups working with copies of students’ work. Peer review can also be conducted electronically. For example, students can exchange drafts by email or respond to one another’s drafts that are posted on the course website. They can also use Word’s comment tool, as illustrated in the following example.

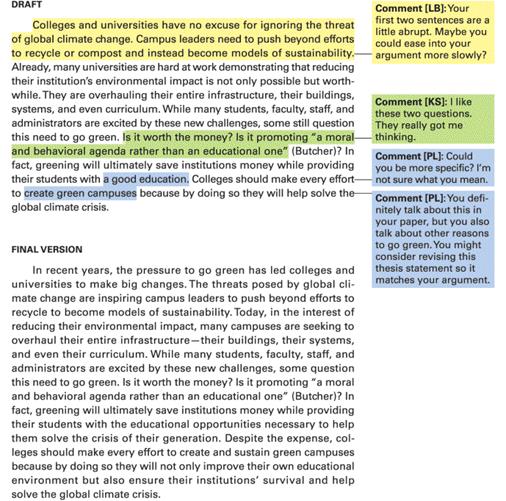

The text reads as follows.

Draft

Colleges and universities have no excuse for ignoring the threat of global climate change. Campus leaders need to push beyond efforts to recycle or compost and instead become models of sustainability. [Annotation reads, Comment [L B]: Your first two sentences are a little abrupt. Maybe you could ease into your argument more slowly?] Already, many universities are hard at work demonstrating that reducing their institution’s environmental impact is not only possible but worthwhile. They are overhauling their entire infrastructure, their buildings, systems, and even curriculum. While many students, faculty, staff, and administrators are excited by these new challenges, some still question this need to go green. Is it worth the money? Is it promoting (open quotes) a moral and behavioral agenda rather than an educational one (close quotes) (Butcher)? [Margin note to the above two questions reads, Comment [K S]: I like these two questions. They really got me thinking.] In fact, greening will ultimately save institutions money while providing their students with a good education. Colleges should make every effort to create green campuses because by doing so they will help solve the global climate crisis. [Margin note pointing to ’a good education.’ and the last sentence reads, Comment [P L]: Could you be more specific? I’m not sure what you mean. Another margin note pointing to the last sentence reads, Comment [P L]: You definitely talk about this in your paper, but you also talk about other reasons to go green. You might consider revising this thesis statement so it matches your argument.]

Final Version

In recent years, the pressure to go green has led colleges and universities to make big changes. The threats posed by global climate change are inspiring campus leaders to push beyond efforts to recycle to become models of sustainability. Today, in the interest of reducing their environmental impact, many campuses are seeking to overhaul their entire infrastructure — their buildings, their systems, and even their curriculum. While many students, faculty, staff, and administrators are excited by these new challenges, some question this need to go green. Is it worth the money? Is it promoting (open quotes) a moral and behavioral agenda rather than an educational one (close quotes) (Butcher)? In fact, greening will ultimately save institutions money while providing their students with the educational opportunities necessary to help them solve the crisis of their generation. Despite the expense, colleges should make every effort to create and sustain green campuses because by doing so they will not only improve their own educational environment but also ensure their institutions’ survival and help solve the global climate crisis.

GUIDELINES FOR PEER REVIEW

Remember that the peer-review process involves giving feedback as well as receiving it. When you respond to a classmate’s work, follow these guidelines:

§ Be very specific when making suggestions, clearly identifying errors, inconsistencies, redundancy, or areas that need further development.

§ Be tactful and supportive when pointing out problems.

§ Give praise and encouragement whenever possible.

§ Be generous with your suggestions for improvement.

![]()

EXERCISE 7.12 REVISING YOUR ARGUMENTATIVE ESSAY

Following the guidelines for revision discussed earlier, get some feedback from others, and then revise your argumentative essay.

Polishing Your Essay

The final step in the writing process is putting the finishing touches on your essay. At this point, your goal is to make sure that your essay is well organized, convincing, and clearly written, with no distracting grammatical or mechanical errors.

Editing and Proofreading

When you edit your revised draft, you review your essay’s overall structure, style, and sentence construction, but you focus on grammar, punctuation, and mechanics. Editing is an important step in the writing process because an interesting, logically organized argument will not be convincing if readers are distracted by run-ons and fragments, confusingly placed modifiers, or incorrect verb forms. (Remember, your grammar checker will spot some grammatical errors, but it will miss many others.)

When you proofread your revised and edited draft, you carefully read every word, trying to spot any remaining punctuation or mechanical errors, as well as any typographical errors (typos) or misspellings that your spellchecker may have missed. (Remember, a spellchecker will not flag a correctly spelled word that is used incorrectly.)

GRAMMAR IN CONTEXT

Contractions versus Possessive Pronouns

Be especially careful not to confuse the contractions it’s, who’s, they’re, and you’re with the possessive forms its, whose, their, and your.

INCORRECT

Its not always clear who’s responsibility it is to promote green initiatives on campus.

CORRECT

It’s not always clear whose responsibility it is to promote green initiatives on campus.

Choosing a Title

After you have edited and proofread your essay, you need to give it a title. Ideally, your title should create interest and give readers clear information about the subject of your essay. It should also be appropriate for your topic. A serious topic calls for a serious title, and a thoughtfully presented argument deserves a thoughtfully selected title.

A title does not need to surprise or shock readers. It also should not be long and wordy or something many readers will not understand. A simple statement of your topic (“Going Green”) or of your position on the issue (“College Campuses Should Go Green”) is usually all that is needed. If you like, you can use a quotation from one of your sources as a title (“Green Is Good”).

![]()

EXERCISE 7.13 EVALUATING POSSIBLE ESSAY TITLES

Evaluate the suitability and effectiveness of the following titles for an argumentative essay on green campuses. Be prepared to explain the strengths and weaknesses of each title.

§ Green Campuses

§ It’s Not Easy Being Green

§ The Lean, Clean, Green Machine

§ What Students Can Do to Make Their Campuses More Environmentally Responsible

§ Why All Campuses Should Be Green Campuses

§ Planting the Seeds of the Green Campus Movement

§ The Green Campus: An Idea Whose Time Has Come

Checking Format

Finally, make sure that your essay follows your instructor’s guidelines for documentation style and manuscript format. (The student paper on p. 278 follows MLA style and manuscript format. For additional sample essays illustrating MLA and APA documentation style and manuscript format, see Chapter 10 and Appendix B, respectively.)

GOING GREEN

SHAWN HOLTON

![]() The following student essay, “Going Green,” argues that colleges should make every effort to create green campuses.

The following student essay, “Going Green,” argues that colleges should make every effort to create green campuses.

Text reads as follows:

(A margin note corresponding to the paragraph reads, Body paragraph: Definition of green as it applies to colleges) Greening a college campus means moving toward a sustainable campus that works to conserve the earth’s natural resources. It means reducing the university’s carbon footprint by focusing on energy efficiency in every aspect of campus life. This is no small task. Although replacing incandescent lightbulbs with compact fluorescent ones and offering more locally grown food in dining halls are valuable steps, meaningful sustainability requires more comprehensive changes. For example, universities also need to invest in alternative energy sources, construct new buildings and remodel old ones, and work to reduce campus demand for nonrenewable products. Although these changes will eventually save universities money, in most cases, the institutions will need to spend money now to reduce costs in the long term. To achieve this transformation, many colleges— individually or in cooperation with other schools—have established formal “climate commitments,” set specific goals, and developed tools to track their investments and evaluate their progress.

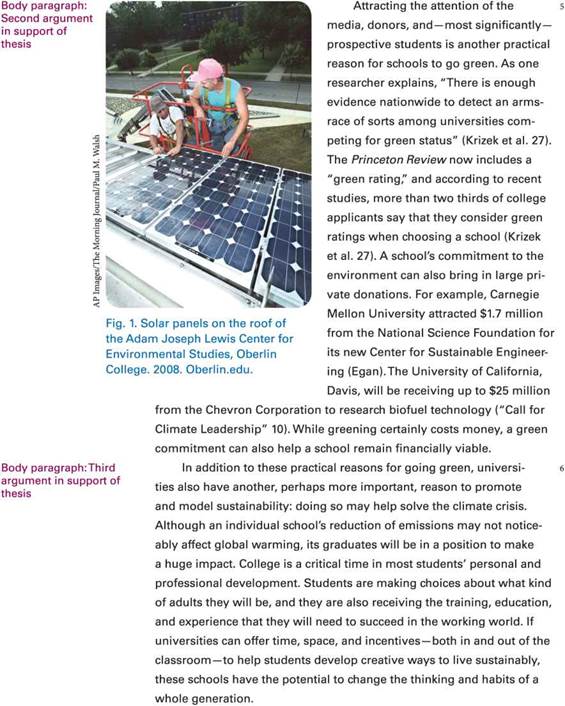

(A margin note corresponding to the next paragraph reads, Body paragraph: First argument in support of thesis) the paragraph reads, Despite these challenges, there are many compelling reasons to act now. Saving money on operating costs, thus making the school more competitive in the long term, is an appealing incentive. In fact, many schools have made solid and sometimes immediate gains by greening some aspect of their campus. For example, by changing its parking and transit systems to encourage more carpooling, biking, and walking, Cornell University has saved 417,000 gallons of fuel and cut costs by $36 million over the last twelve years (“Call for Climate Leadership” 10). By installing geothermal wells and replacing its old power plant with a geothermal pump system, the University of Central Missouri (UCM) is saving 31 percent in energy costs, according to a case study in Climate Neutral Campus Report (Trane). These changes were not merely a social, or even a political, response, but a necessary part of updating the campus. Betty Roberts, the UCM vice president for administration, was faced with the problem of how to “make a change for the benefit of the institution . . . with no money.” After saving several million dollars by choosing to go green, Roberts naturally reported that the school was “very happy!” with its decision (qtd. in Trane). There is more to be gained than just savings, however. Oberlin College not only saves money by generating its own solar energy (as shown in Fig. 1) but also makes money by selling its excess electricity back to the local power company (Petersen). Many other schools have taken similar steps, with similarly positive results.

Text reads as follows:

Many critics of greening claim that becoming environmentally friendly is too expensive and will result in higher tuition and fees. However, often a very small increase in fees, as little as a few dollars a semester, can be enough to help a school institute significant change. For example, at the University of Colorado—Boulder, a student-initiated $1 increase in fees allowed the school to purchase enough wind power to reduce its carbon emissions by 12 million pounds (“Call for Climate Leadership” 9). Significantly, the students were the ones who voted to increase their own fees to achieve a greener campus. Although university faculty and administrators’ commitment to sustainability is critical for any program’s success, few green initiatives will succeed without the enthusiastic support of the student body. Ultimately, students have the power. If they think their school is spending too much on green projects, then they can make a change or choose to go elsewhere. (A margin note corresponding to the paragraph reads, Refutation of first opposing argument.)

Other critics of the trend toward greener campuses believe that schools with commitments to sustainability are dictating how students should live rather than encouraging free thought. As one early critic has claimed, “Once [sustainability literacy] is enshrined in a university’s public pronouncements or private articles, then the institution has diminished its commitment to academic inquiry” (Butcher). This kind of criticism overlooks the fact that figuring out how to achieve sustainability requires and will continue to require rigorous critical thinking and creativity. Why not apply the academic skills of inquiry, analysis, and problem solving to the biggest problem of our day? Not doing so would be irresponsible and would confirm the perception that universities are ivory towers of irrelevant knowledge. In fact, the presence of sustainability as both a goal and a subject of study has the potential to reaffirm academia’s place at the center of civil society. (A margin note corresponding to the paragraph reads, Refutation of second opposing argument.)

Creating a green campus is a difficult task, but universities must rise to the challenge or face the consequences. If they do not commit to changing their ways, they will become less and less able to compete for students and for funding. If they refuse to make a comprehensive commitment to sustainability, they also risk irrelevance at best and institutional collapse at worst. Finally, by not rising to the challenge, they will be giving up the opportunity to establish themselves as leaders in addressing the climate crisis. As the coalition of American College and University Presidents states in its Climate Commitment, “No other institution has the influence (text continues on the next page and a corresponding margin note reads, Conclusion).

Text continues as follows:

the critical mass and the diversity of skills needed to successfully reverse global warming” (“Call for Climate Leadership” 13). Now is the time for schools to make the choice and pledge to go green (corresponding margin note reads, Concluding statement).

Works Cited

Butcher, Jim. “Keep the Green Moral Agenda off Campus.” Times Higher

Education, 19 Oct. 2007, www.timeshighereducation.com/news/keep-the-green-moral-agenda-off-campus/310853.article.

“A Call for Climate Leadership.” American College and University Presidents

Climate Commitment, Aug. 2009, www2.presidentsclimatecommitment.org/html/documents/ACUPCC_InfoPacketv2.pdf.

Egan, Timothy. “The Greening of America’s Campuses.” New York Times, 8

Jan. 2006, www.nytimes.com/2006/01/08/education/edlife/egan_environment.html?scp=1&%3Bsq=The&_r=0.

“Environmentalism.” Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, 2015, www.britannica.com/topic/environmentalism.

Krizek, Kevin J., Dave Newport, James White, and Alan R. Townsend. “Higher

Education’s Sustainability Imperative: How to Practically Respond?”

International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, vol. 13,

no. 1, 2012, pp. 1—33. DOI: 10.1108/14676371211190281.

Petersen, John. “A Green Curriculum Involves Everyone on Campus.” Chronicle of Higher Education, vol. 54, no. 41, 2008, p. A25. ERIC Institute of

Education Services, eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ801316.

Trane. “University of Central Missouri.” Climate Neutral Campus Report,

Kyoto Publishing, 14 Aug. 2009, secondnature.org/wp-content/uploads/09-8-14_ClimateNeutralCampusReportReleased.pdf.

![]()

EXERCISE 7.14 PREPARING A FINAL DRAFT

Edit and proofread your essay, paying special attention to parenthetical documentation and to your works-cited page, and check to make sure your essay’s format is consistent with your instructor’s requirements. When you have finished, give your essay a title, and print out a final copy.

![]()

EXERCISE 7.15 EVALUATING VISUAL ARGUMENTS

Write a paragraph in which you evaluate the visual in the student essay on pages 278—82. Does it add valuable support to the essay, or should it be deleted or replaced? Can you suggest a visual that could serve as a more convincing argument in support of green campuses?