Putting the science in fiction - Dan Koboldt, Chuck Wendig 2018

Crafting holograms

Things to know for when Skynet takes over

By Judy L. Mohr

Imagine driving through a parking garage looking for a perfect place to park. You find one just outside the main doors. You turn on your indicator and start to pull in.

STOP! A man in a wheelchair has appeared out of nowhere. You almost ran over him. Thinking that you could have killed this handicapped fellow, you step out of your car to apologize. As you walk around your car door and move closer to the man, you notice something odd. He’s thin—as in 2D thin. He’s not real. Yet his image is as clear as anything. Stunned, you stare at this image of a man in a wheelchair while he tells you that your perfect parking spot is actually a handicapped spot. A hologram wants you to park somewhere else.

Feeling guilty and sheepish, you get back into your car and look for another place to park.

It may sound like fiction, but it’s not. Scientists in Russia have combined detection-and-recognition technologies with projection systems to solve a very real issue. If a handicap placard is not detected on your vehicle, an image of the man in the wheelchair is projected onto a curtain of mist directly in front of you. The image is very convincing, but is this really a hologram?

According to Merriam-Webster and the Oxford English Dictionary, a hologram is a 3D image formed from the interference patterns of a coherent light source. Put simply, a hologram is a virtual 3D image. It does not need a screen to be seen, nor does it need a source of monochromatic light. All that is needed is a light source of known, determinable characteristics and surfaces to bounce the light around. For something to truly be classified as a hologram, you should be able to look at the image from multiple directions, getting a feel for the 3D object hovering in empty space.

The Russian man in a wheelchair is actually just a 2D projection, but still a very convincing one—and one I would love to see in other countries around the world.

So, what about real holograms?

It started with star wars

In 1977, R2-D2 projected an image of Princess Leia onto the big screen and the mainstream idea of using holograms for telecommunications was born. However, George Lucas was not the first one to come up with the idea. What the public didn’t know was that holograms already existed.

The first hologram was produced in 1947 by the British scientist Dennis Gabor while trying to improve the resolution of electron microscopes. With the advancement of lasers in the 1960s, holography developed into our current understanding of 3D-image transmission. In 1972, Lloyd Cross combined white-light transmission holography with conventional cinematography to produce moving 3D images from a sequence of recorded 2D images of a rotating object. So when George Lucas added holographic technologies to his futuristic story, it was by no means a stretch of the imagination.

However, I must admit that I’m still trying to figure out how R2-D2 was able to take an image of Leia’s back when she was facing him during the recording, but we’ll ignore that little detail.

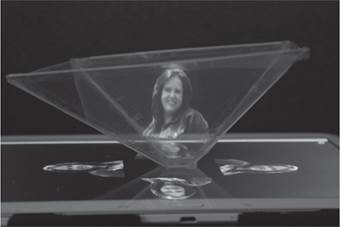

Creating large-scale 3D images showing different views from all angles, similar to those portrayed in the Star Wars franchise, is not completely beyond the realm of our current technology. With clear, reflective plastic (or glass) and the right app, you can turn your smartphone or tablet into a holographic projector (Figure 37.1).

Figure 37.1: Using the plastic from CD cases, you can turn your smartphone or tablet into a holographic projector.

You can find many articles on the Internet detailing how to use the clear plastic from a CD case and your smartphone to create a moving holographic image of a jellyfish (or some other creature). There are even videos on YouTube that are designed specifically to use for the purpose. It’s a fun activity to do with children that shows them how reflection works to form virtual images. (Actually, you don’t need to have children to do this experiment—just an inquisitive mind.)

There are readily available units that use mirrors to magnify and project 3D virtual images of Matchbox cars and rubber frogs in free air. They come in a range of sizes, and every time I see one, the urge to pass my fingers through the image is uncontrollable. If you were to combine these simple holographic projectors with the current videophone technologies, the talking, interactive hologram used for communications in Star Wars instantly becomes a reality.

But what about the best holographic idea that science fiction has to offer: the holodeck from Star Trek: The Next Generation? I don’t know about anyone else, but I remember sitting with my parents, gathered around the TV in awe as the first episode aired in 1987. Already big fans of Star Trek, my mother constantly begging to have a replicator, it was a collective “I want one” when we saw Riker open the doors to the holodeck and walk into the forest.

Unfortunately, unlike the holograms of Star Wars, the holodeck and its fully interactive environment are something we will never see. Projection systems may progress to the point that the 3D images are indistinguishable from reality; however, just the presence of a solid object would disrupt the image, creating shadows and distortions. This idea becomes further complicated with the fact that light cannot stop matter.

The scientific models for light can be incredibly confusing, with the ray and wave models used to describe reflection, refraction, and interference. Add the quantum model into the mix and even this scientist is lost. However, I can appreciate that current laser technology could potentially stop something with mass, but only by burning it to a crisp and blowing it up. Physical, tactile interactions with light are out of the question—at least the kind that won’t injure us are out of the question. If you try to sit in a holographic chair, you will fall to the floor and potentially hurt your bum.

For the moment, I’ll just ignore science fiction’s suggestion that we might physically interact with holograms, enjoying a cup of tea with historic holographic characters. Regardless, projection and holographic-related systems have already had an impact on our everyday life—and it all starts with a pseudo-hologram telling you to park somewhere else.