English grammar - Roger Berry 2012

A9.2 Types of sentence

A9 Types of sentence

Section A. Introduction

In order for us to talk about grammar at the sentence level, it helps to make a number of distinctions:

1. Major (or regular) sentences vs minor (or irregular) sentences. The purpose of this distinction is to distinguish the type of sentence we are interested in, namely major sentences. Minor sentences are incomplete; they lack some important element. There are various types; thus to a question such as When will she come? we might get the following responses:

In the afternoon. (a prepositional phrase)

Before her sister does. (a subordinate, adverbial, clause - see A10)

Tonight. (an adverb/adverb phrase)

Next week. (a noun phrase)

These responses all have some grammar, but not on the sentence level, in that they constitute adverbials in terms of clause elements. They are sometimes called ’fragments’, since they can be seen as part of a major sentence. We can construct a major sentence for all of them using the original question, for example:

She will come in the afternoon.

There is one other type of minor sentence, so-called ’non-sentences’, for example: No smoking. / Silence!

Such non-sentences are typical of signs and headlines. Although they may have some grammar at the phrase level (e.g. the fact that there is a determiner preceding a noun in No smoking), they are different from fragments in that it is not certain what the equivalent major sentence should be: Smoking is not allowed (?), There is no smoking here (?).

Activity A9.1

Say whether these newspaper headlines are major or minor sentences.

1. Ailing Maggie in hospital. (ailing = ’sick’)

2. Save our schools by restoring teachers’ authority.

3. End to reading classes.

4. How your money is spent by the state.

2. Simple sentences vs multiple sentences. This distinction applies to major sentences. A simple sentence is one consisting of only one clause, while a multiple sentence consists of more than one clause. Since we have already dealt with the construction of clauses in A8, this section is mainly interested in multiple sentences, i.e. how clauses are combined.

3. Compound sentences vs complex sentences. These are two types of multiple sentence, reflecting the two main ways in which clauses are combined. They are discussed below.

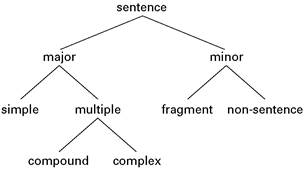

This diagram shows the relationship between the various kinds of sentence described above:

Figure A9.2.1 The relationship between different types of sentence

Activity A9.2

Look at this short paragraph taken from the text in C9 and answer the question underneath. The numbers in brackets indicate graphological sentences.

(1) Here is how I came to love my mother. (2) How I saw in her my own true nature. (3) What was beneath my skin. (4) Inside my bones.

There are four graphological sentences, but how many grammatical ones are there?

Multiple sentences

Multiple sentences are those where two or more clauses are combined. There are two types of combination: co-ordination and subordination. With co-ordinated clauses, two or more clauses of equal importance are joined, in series; a co-ordinating conjunction (see below) is usually inserted, for example:

She works hard, has an enquiring mind and is popular with her colleagues.

Here there are three clauses. Such sentences are called ’compound’, and the clauses are called ’main’.

The other type of clause combination is subordination. In this, one clause of lesser importance, a subordinate clause, is added to a main clause:

I like him because he is different.

In this example the subordinate clause can be regarded as an adverbial of the main clause. Such sentences are called ’complex’.

Main clauses are sometimes called ’independent’ clauses, because it is thought that they can stand on their own, while subordinate clauses cannot. While this would apply to the example above (I like him), it does not apply to all cases:

He said that he wasn’t coming.

Here we cannot just say He said, because that he wasn’t coming is the object and the verb say requires an object. Subordinate clauses always represent a part of the main clause, either as a clause element, as above, or as part of a clause element, as in this example:

Where did you put the pen I lent you?

Here I lent you is part of the object the pen I lent you.

Complex sentences can become quite complicated especially in some kinds of writing, and it is possible to find both types of combination in the same sentence, i.e. compound-complex sentences (see C10).

The different types of subordinate clause are described in some detail in A10.