Teaching information literacy and writing studies - Grace Veach 2018

Are they really using what i’m teaching?

Making a Difference

AAC&U’s 2015 report “Trends in Learning Outcomes Assessment” notes that institutions have prioritized research skills, as 76% of member institutions reported student learning outcomes for information literacy. The effectiveness of this emphasis is complicated by studies conducted by Project Information Literacy (PIL), which suggest students experience difficulty initiating research projects, determining information need, and evaluating sources (Head, 2013). As institutions emphasize information literacy, writing instructors and librarians must collaborate to determine what curricular revisions are needed to enact best practices in both information literacy instruction and composition pedagogy. Such collaboration and curricular work have been inhibited by disciplinary jargon (Carter & Alderidge, 2016); by a paucity of scholarship exploring theoretical articulations between information and library sciences and rhetoric and composition (Mazziotti & Grettano, 2011); and by writing instructors’ lack of exposure to scholarship on information literacy (D’Angelo & Maid, 2004; Deitering & Jameson, 2008; Mazziotti & Grettano, 2011).

This chapter contributes to an interdisciplinary conversation regarding the dynamic interrelationship between information literacy and writing by describing a collaborative assessment project at a small liberal arts college in the Midwest in which a librarian partnered with a writing program administrator and an assessment scholar as part of the American Library Association’s “Assessment in Action” initiative. This ongoing, IRB-approved project applies dynamic criteria mapping (DCM), a qualitative, constructivist method of writing assessment where librarians and writing faculty defined information literacy and engaged in interdisciplinary conversations, developing consensus on what they value when they read first-year writing projects in light of research skills and information literacy and reconciling disparate disciplinary terminology. This chapter frames the DCM performance-based method for assessing information literacy that counters methods, like rubric scoring, prevalent within information and library sciences (Belanger, Bliquez, & Mondal, 2012), and that aligns “form and content of the assessment method” with “instructional goals” within both information literacy and writing programs (Oakleaf, 2008 p. 242). First, this chapter presents DCM as an assessment methodology and describes how it was applied at Elmhurst College. Then, the chapter explains important products of the process: a criteria guide and a criteria map. Finally, it describes how the project presents important interdisciplinary implications.

DYNAMIC CRITERIA MAPPING

Assessment of information literacy (IL) instruction concerns teaching librarians attempting to understand the effect of their instruction on student learning (Gilchrist, 2009). However, since IL instruction often occurs in “one-shot” sessions (Artman, Frisicaro-Pawlowski, & Monge, 2010) and since librarians rarely have access to student artifacts, authentic assessment of IL instruction remains difficult. Assessment, though, provides unique opportunities for collaboration among librarians and writing instructors, for highlighting the importance of IL, and for acquiring evidence of student learning (Belanger, Zou, Mills, Holmes, & Oakleaf, 2015). Research on best practices in IL instruction describes the positive impact of collaborative efforts between librarians and classroom faculty (Barratt, Nielsen, Desmet, & Balthazor, 2009; Belanger et al., 2012), suggesting the need to conceptualize assessment as an important component of best practices.

In considering appropriate assessment methods, practitioners should consider dynamic criteria mapping, a site-based, locally controlled process that responds to the needs and circumstances of a community (Broad, 2003). Writing assessment scholarship frames DCM as organic, generative, and qualitative. As an organic assessment process, it engages the experience and knowledge of practitioners rather than outsourcing assessment to a commercial testing corporation, like Pearson. It is fundamentally focused on a specific community, encouraging practitioners to articulate and then cultivate consensus on what they value when they evaluate and assess student products in individual courses and/or during programmatic assessment processes (Broad, 2003). Underlying dynamic criteria mapping is social-constructivist theory, which privileges an epistemological framing of knowledge as constructed through social processes, like intensive discussion sessions, involving competing perspectives, values, power relations, and levels of expertise. DCM purposely addresses these complexities to identify how disciplinary knowledges and social dynamics influence the evaluative process. It contrasts sharply with traditional assessment processes, which are informed by a positivist psychometric epistemological framework that conceptualizes knowledge as precisely discernible and reality as distinctly stable and objectively known and knowable (Huot, 2002).

As a generative and qualitative practice, DCM encourages participants to verbalize and understand the specific criteria they apply when evaluating student products, identify textual features of student products fulfilling privileged criteria, and link criteria to learning outcomes for courses and programs (Broad, 2003). Enriching the generative process, participants think critically about the respective value of each and make articulations among evaluation criteria, textual features, and learning outcomes. DCM is also framed as a qualitative method of assessment because it elicits a variety of qualitative data, like marginalia on student artifacts, participant notes, and transcripts of small- and large-group discussion sessions. One key product of the DCM process is the creation of a visual representation that not only identifies privileged criteria but also conveys the dynamic relationships among them (Broad, 2003). This visual representation, or criteria map, portrays participant consensus regarding what they value; what criteria matter and why; and how criteria interrelate when participants apply them when evaluating student artifacts (Appendix A).

DCM AT ELMHURST COLLEGE

DCM’s site-based, organic focus makes it adaptable to a variety of institutional contexts, ranging from community colleges to flagship state universities (Broad et al., 2009). For several reasons, DCM was a particularly compelling methodology to cultivate consensus on IL at Elmhurst College, a liberal arts institution with approximately 3,200 undergraduate and graduate students. One, precipitated by the financial stresses of the Great Recession and by the implementation of a corporate model of administration, distrust and skepticism permeated institutional dynamics and interdepartmental relationships, causing many faculty to presume that assessment enacts ulterior motives, like the curtailment of programs. It is impossible to develop a culture of assessment if faculty not only devalue assessment but also perceive it as a means to ominous ends (Behm, 2016; Janangelo & Adler-Kassner, 2009). Two, resulting from a long history of indifference to assessment, the college lacked empirical evidence of student learning, a deficiency gently admonished by a 2009 Higher Learning Commission (HLC) report. Three, across campus, practitioners have heretofore neither asserted ownership of assessment nor cultivated consensus on learning outcomes and criteria related to IL. This institutional context provided a unique crucible, then, in which to implement DCM and realize its benefits (see Box 18.1), because it privileges collaborative discussion, ultimately building trust, collegiality, and consensus.

BOX 18.1

BENEFITS OF DYNAMIC CRITERIA MAPPING (DCM)

✵Privileges Qualitative Writing Assessment

✵Conceptualizes Assessment as a Social Process

✵Reveals What a Community Values

✵Renders Evaluative Dynamics Visually

✵Clarifies the Semantics of Criteria

✵Facilitates Professional Development

✵Builds a Culture of Assessment

(Data from Broad, 2003.)

Lacking consensus regarding learning outcomes and criteria related to IL, the most logical starting place was to engage English faculty and librarians in the process of clarifying their diverse understandings of IL: how they conceptualize it as a disposition and practice, what features distinguish IL within written products, and what aspects of IL they value and why. To do this, we designed a three-day DCM process that progressed inductively from individual close reading of student artifacts to successive small- and large-group intensive discussions during which 11 participants (six librarians and five writing instructors) articulated their disparate conceptions of IL but ultimately reached consensus on a shared understanding of IL and vocabulary, building a bridge across our disciplinary division. Students in six sections of first-year writing signed informed consent forms and submitted their academic argument essays. The 11 faculty participants of the DCM process also provided informed consent. Since essays were used only to springboard discussion as part of clarifying participants’ expectations, we chose six essays for review. Though we delineate the steps sequentially below, in actual practice, DCM methodology functions recursively as participants generate ideas, identify and negotiate criteria, find common ground, and foster community.

The first step of our DCM process involved a brief introduction conceptualizing the project and explaining dynamic criteria mapping methodology. Participants then individually reviewed six student artifacts. To elicit participants’ preconceptions of IL and how IL is demonstrated by written artifacts, participants provided marginalia on the artifacts, took notes, and completed a worksheet with the following questions: (1) Does this text demonstrate information literacy (Y/N)? Why? (2) What rationale can you provide for deciding as you did? (3) What aspects or characteristics of the sample texts do you value, privilege, or emphasize? (4) Why do you value those aspects/characteristics? (5) What do they reflect, represent, and/or demonstrate? The review of student artifacts not only fostered discussion of IL but also grounded and focused that discussion. For instance, it was students’ demonstration of IL that served as the impetus for participants to articulate and think critically about how they conceptualize IL. Also, if discussion veered unproductively, we could always return to the artifacts. The writing of marginalia, taking of notes, and responding to questions was critical in encouraging participants to express their respective definitions of IL, provide a rationale supporting that definition and their interpretation of the student artifacts, identify textual features that exhibit IL, and describe why they privileged those features and what those features represented within student writing.

The second step involved participants working in groups of three or “trio groups.” With 11 participants, we divided participants into three groups of three and one group of two. In DCM methodology, small- and large-group work is framed as articulation sessions. Noting evaluative comments, criteria, and textual features delineating IL, the trio groups provided space for participants to discuss their respective interpretations of each text. Each trio group audio-recorded their discussion and participants took notes as well. Trio groups labored to generate consensus on a conception of IL, on what comprises it, and on what specific textual features and characteristics of student artifacts demonstrate IL.

The third step involved an articulation session with all participants during which each trio group presented their privileged comments, criteria, and textual features and described how each group cultivated consensus. The focus of the large-group discussion was to identify comments, criteria, and textual features; group synonymous comments and criteria together; and categorize them as constellations, a process of describing and framing the data in a way that makes it more amenable to visual representation as a map. Through this work, participants fostered consensus on a framing of IL as a developmental process and disposition toward information and knowledge that is active and engaged. The group also generated consensus on what comments and criteria ought to be emphasized and how we could combine and categorize them appropriately (see Appendix A).

After cultivating consensus as a large group, we moved to the fourth step: collaborating in the construction of a useful visual representation of that consensus that accurately portrayed how the group defines and describes IL, a rendering that could be shared with the Elmhurst College community, particularly students, to clarify the expectations of librarians and writing instructors. Another critical part of this step was to foster consensus among the group regarding the dynamics of how our privileged comments, criteria, and textual features interrelated to portray our framing of IL. With dynamic criteria mapping, not only is it critical to articulate privileged criteria, but also to convey visually the relationships among those criteria as they are applied when practitioners review and evaluate student artifacts.

The last step consisted of a debriefing session where participants discussed their experience with our dynamic criteria mapping methodology, noting challenges and providing feedback on how the exercise might be modified and improved in the future. The group also discussed how the criteria guide could inform future IL sessions, improve student learning, enrich strategies for teaching IL in first-year writing courses, and influence future assessment practices.

FROM CRITERIA TO MAP

The primary purpose of DCM is to make explicit, through small- and large-group discussion and critical reflection, what a community really values when assessing and evaluating student work (see Box 18.2 for the data analysis procedure). The criteria lists generated during our articulation sessions present a comprehensive, yet messy, view of what our community values in terms of IL (Appendix A). Criteria that were repeated frequently, like source/s, complicated/complexity, and integration, reflected what group participants considered important. Some of these criteria were more “honored in the breach,” in that participants felt the papers lacked the quality/criteria rather than demonstrated it. In our large-group discussion, we worked on grouping the criteria into constellations that reflected both the importance of the criteria and also the group’s conceptual consensus about their underlying significance. Ultimately, the constellations articulated by the large group were the following:

✵Process: awareness of information need, searching, source choice

✵Praxis/Enactment: synthesis/deployment of sources, awareness of context/perspectives/conversation, awareness of bias

✵Engagement: cognition/metacognition, persistence, disposition of inquiry

✵Attribution: mechanics of citation, paraphrasing

BOX 18.2

DATA ANALYSIS

Data Collected

✵Workshop participant worksheet responses

✵Marginalia respondent notes collected from sample papers

✵Recording of trio- and large-group discussion (transcript)

Initial Analysis

✵All material transcribed to Google docs

✵Text search used to identify and locate relevant IL words/descriptors

✵Each investigator also engaged in close reading of the texts

Constellation-Building Process

✵Investigators compiled lists of criteria words/terms/concepts

✵Word/term/concept groupings

✵Themes emerge

✵Themes become “constellations”

A note on analytic software: Although we had access to NVivo, the learning curve was steeper than anticipated given time constraints.

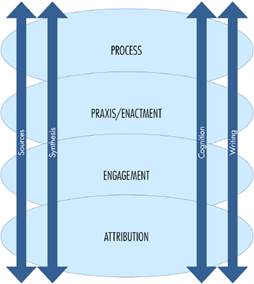

The sorting of the criteria into the constellations provided some interesting perspective. As the investigators sorted criteria into the constellations, it became apparent that two constellations, Praxis/Enactment and Engagement, were privileged, gaining the most criteria. We also noted that Attribution, though a necessary constellation, drew the fewest descriptors. Once the constellations and criteria were analyzed, we visually represented the relationships among the constellations. Our map uniquely represents the values expressed by the community and reflects how we see the constellations as overlapping. Though we initiated the map-making process during a large-group articulation session, time constraints necessitated that we construct the map after closely analyzing the data.

The elements of the map consist of the constellations (Process, Praxis/Enactment, Engagement, Attribution), as well as elements that connect and flow between them—Sources, Synthesis, Cognition, and Writing are the means by which these concepts are enacted. These terms were repeated in our criteria enough that we felt they needed to be explicitly part of the map itself. They seemed to us to be structurally integral to explaining the relationships between the constellations, and added a representation of movement between the constellations.

The map itself (Figure 18.1) came out of discussions between the investigators and data analysis, and resulted from an intuitive leap by one of us while trying to articulate the movement and relationship among the constellations and the process-oriented elements. In DCM, the development of the map is a creative process. We benefited from allowing time for thoughtful processing. Several of the meetings between investigators were spent drawing things on paper and then throwing them away. This was a crucial part of the process and led to our having a map that really reflects our process and our community values. Our map portrays IL as a fluid process-oriented activity that students move through in a recursive way.

Figure 18.1 Dynamic criteria map.

INTERDISCIPLINARY IMPLICATIONS OF THE PROJECT

Our process of applying DCM generated three important interdisciplinary implications: that writing and research are interrelated, that the DCM process can generate a shared language describing IL, and that disciplinary documents can possibly enable interdisciplinary collaborations and coalitions.

Writing and Research Are Interrelated

Participants agreed that writing and IL are interrelated and that student writing is useful in assessing IL. These essays were a valuable resource for assessing IL in terms of students’ process and product. For instance, participants determined the extent to which students were comfortable with complexity and were aware of how research and writing enriched their perspectives and influenced their understanding of audience awareness and research needs as the projects unfolded. This exploration of student writing was particularly useful to the librarians. Because librarians typically don’t have access to student products, they tend to focus on process. Having the opportunity to read student papers and see the enactment of the research process in student work helped librarians explicitly see that connection between writing and IL. The IL and writing criteria were inextricably linked so that while the constellations (Appendix A) developed with a focus on IL, the writing faculty and librarians could not separate the writing from the research. One librarian remarked on the “firm agreement in quality and criteria amongst a small pool of reviewers, as it illustrates and validates that we have a pretty common definition of a ’good’ research essay.” Similarly, a writing instructor did not see “a considerable amount of conflict between what we have articulated as IL and how it functions in the classroom. There appears to be some discussion about what the level of proficiency should be in first-year students; however, I have found the discussion to be incredibly useful and illuminating.”

By its very nature as a radically situated process, DCM resulted in participants’ experiences paralleling students’ struggles with the academic research essay. Participants needed to experience the DCM process to understand the complexity of what we were asking students to do within a limited time period and what we valued in that process and those products. Students can’t “pre-answer” their research questions just as practitioners can’t subscribe to an ideal text that students are not developmentally ready to produce. Our initial review of essays applied our respective ideal texts. The insights emerging from the cross-disciplinarity of our group discussions, however, made us recalibrate our expectations so that we reviewed the essays as first-year students’ initial attempt at entering an academic community, a reflection of the developmental nature of cultivating proficiency in IL and writing. One writing instructor observed how “during this workshop, it seems that we arrived at the right questions and became aware of the gap between our standards and student performance.” For instance, we observed that students were using at least some library sources. Works Cited lists included many books, encyclopedia entries, and articles both scholarly and popular gleaned from databases. But one developmental marker for us was that, although students found sources, their writing revealed their inability to understand and skillfully deploy that material in service of an argument, which may indicate that students lack the metacognitive skill required to successfully integrate sources in support of an argument.

Interdisciplinary Conversation and Collaboration

Librarians and writing faculty both facilitate student learning, though their approaches and disciplinary jargon vary. However, DCM enables useful interdisciplinary conversation. Participants discovered that although the vocabulary/language we used to describe and articulate student demonstrations of IL differ, our group discussions allowed us to unpack semantics and revealed that we value similar demonstrations of IL, even if we initially used different words to articulate criteria. For example, one criterion that emerged revolves around the “why” of IL. Both librarians and writing faculty assign value to students understanding the intellectual underpinning of IL practices, like source citation. Librarians and writing instructors value the correct use of citation, but the different disciplinary approaches lead to different “whys.” Librarians often use citations as a locator: the accuracy of a citation dictates its usefulness in harvesting additional sources. However, for writing instructors, citation reflects students’ location in a discourse and recognition of a source’s authority within a discourse. A writing instructor checks sources to ensure students are maximizing their rhetorical agenda. Our discussions allowed us to consider disciplinary perspectives, deepening our understanding of how we can work concertedly to develop student learning. A veteran librarian noted that “while we are speaking of terms from two different disciplines of librarianship and teachers of English, we have the same goals and many overlap. We may also view these goals through different lenses but our end point is the same.” A shared—and expanding—vocabulary also emerged from this assessment project. One librarian intended “to be more purposeful in what I say to students.”

Some participants attributed this shift to the shared meanings and varied synonyms that represent and clarify the constellations (see Appendix A), and others commented that hearing the perspective of someone in another discipline helped them see and name things they couldn’t before. One writing instructor used the simile of a ball. She imagined that “if what we’re talking about is like a ball, I’m looking at this part of the ball and the librarian might be looking at this part of the ball—the lenses—and it’s really helpful for me for the librarian to describe what I’m looking at.” She explained how this librarian perspective “forces me to re-prioritize in my own head what it is that students are supposed to get out of my class. Now I have a better image of what other expectations are and what other understandings of the subject are.” This different perspective—and different language—expands one’s approach. And a librarian, who had previously described the criteria as “cumbersome,” in fact agreed that “I feel the same way from a library science perspective.”

Articulations Between the Framework(s)

Before this DCM process, practitioners were aware of the national conversation about IL and writing as they have been enshrined in disciplinary documents, like the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (IL Framework; ACRL, 2016) and the Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing (Writing Framework; CWPA, 2011). While not anticipated, our criteria guide closely corresponded with and easily revealed discernible connections between these disciplinary documents. We identified Framework categories as speaking to our initial list of criteria (see Appendix B), and believe that highlighting the connections between the documents could initiate productive interdisciplinary collaborations and coalitions. For example, the IL Framework articulates lenses that generally correspond to the Writing Framework, like practices and dispositions. This approach—what students do and their orientation toward the process—parallels the “habits of mind” that “refers to ways of approaching learning that are both intellectual and practical and that will support students’ success in a variety of fields and disciplines” (p. 1). Thus, the intellectual/disposition components of the process and practices/practical aspects encompass both an approach to writing and research and an enactment. Both frameworks emphasize metacognition with the Writing Framework devoting a section to it and the IL Framework founded on “these core ideas of metaliteracy, with special focus on metacognition, or critical self-reflection, as crucial to becoming more self-directed in that rapidly changing ecosystem” (p. 3). Our criteria include characteristics, like curiosity, recursivity, and persistence, that speak to the necessity for awareness and reflection on the part of the student writer.

Unlike the Writing Framework, the IL Framework talks explicitly about issues of power. In our reading of student papers, we found that the research frequently overpowered student writers in terms of their inability to understand and synthesize material as well as their facility in maintaining a strong voice and stance. The IL Framework maintains that even though “novice learners and experts at all levels can take part in the conversation, established power and authority structures may influence their ability to participate and can privilege certain voices and information” (p. 8). Writing instructors and librarians felt that students lacked “fluency in the language and process of a discipline,” but rather than allowing this inexperience to disempower their “ability to participate and engage” (p. 8), our job as educators is to highlight entry points for students. For librarians, that might mean showing students encyclopedias that can facilitate access to the more in-depth scholarly conversation. For writing faculty, that might mean asking students to incorporate narrative elements, like personal anecdotes, into their arguments, or helping students formulate research questions that connect to their lived experiences, which allows students to understand their place in the scholarly conversation while still possessing the confidence to participate. Developmentally, students are being asked to “appropriate (or be appropriated by) a specialized discourse, and they have to do this as though they were easily and comfortably one with their audience” (Bartholomae, 1986, p. 9). While “their initial progress will be marked by their abilities to take on the role of privilege, by their abilities to establish authority” (Bartholomae, 1986, p. 20) this process may, ironically, be characterized by inconsistencies and false steps. Thus, given the place of first-year writing in the curriculum and in a student’s undergraduate career, students may come to the institution with extensive learning needs regarding IL and writing. The criteria that practitioners generate through DCM must not ignore the institutional context and students’ positions within that structure.

At the disciplinary level, the articulations between the IL Framework and the Writing Framework, particularly the dual emphasis on dispositions and practices, serve as an opportunity for future scholarship in both library science and rhetoric and composition. There is much that both disciplines could learn from each other, and the articulations between the respective frameworks could generate productive collaborative relationships among librarians and writing instructors, providing a shared discourse with which to not only unpack and understand disciplinary pedagogical and theoretical differences but also cultivate an awareness of the complex intercalations of IL and writing. At the programmatic level, this shared discourse and understanding could springboard discussions of how to design effective information literacy instruction; demystify the complex relationship between writing and information literacy for students; articulate pertinent, measurable learning outcomes; and construct programmatic professional development opportunities. For us, getting to know our colleagues in library science and rhetoric and composition through the DCM experience of assessment and the process of comparing the two disciplinary frameworks was one of the most rewarding outcomes, enabling us to find theoretical and pedagogical common ground. What is more, the iterative nature of the DCM discussion gave us the opportunity to think through the messiness of the evaluative process, helping us discover values we might not have recognized and requiring us to consider them critically as part of generating consensus about criteria and developing clear expectations that both librarians and writing faculty hold. Ultimately, applying DCM methodology, we generated consensus on how to conceptualize information literacy and engaged in interdisciplinary conversations that strengthened coalitions among librarians and writing faculty and initiated additional assessment projects.

NOTE

We would like to thank Ted Lerud, former Associate Dean of the Faculty; Susan Swords Steffen, Director of the A. C. Buehler Library; and Ann Frank Wake, Chair of the English Department, for their ongoing support of this project and the following participants: Librarians Donna Goodwyn, Jacob Hill, Elaine Page, and Jennifer Paliatka; and writing faculty members Erika McCombs, Michelle Mouton, Mary Beth Newman, Bridget O’Rourke, and Kathy Veliz.

APPENDIX A. IL Criteria Guide for English Composition Researched Arguments

Process |

Praxis/Enactment |

Engagement |

Attribution |

Library (Re)sources Range of Sources Number of Sources Source Genre Academic Sources Scholarly Sources Analytical Awareness Relationships among Source Material Appropriateness of Source Material Relevance Knowing Information Need Credibility/Credible Quotes Cite/Citation/Cites Digging Deeper Grappling with Viewpoints Curious Researcher Inquiry Recursive Complexity of Topic Curiosity |

Command of Research and Argument Thesis Facilitate an Argument Analytical Awareness Bias Awareness Resisting Confirmation Bias Cherry Picking Conversation Explore Conflicting/Complex Integration/Incorporation Claim Facts, Evidence, & Examples Support Synthesize Sources Contextualizing Source Material Grouping Sources Acknowledging Perspectives Discerning the Credibility of Sources Paraphrase Quote Synthesis Agency Demonstration of writing skills and of Being Informed about an Issue |

Persistence Inquiry Grasp Engaged Curious Recursive Understood Interpret Inability to Distinguish Information from Opinion Accommodation of Alternative Perspectives Contrast Sides Dialogue Complexity Rhetorical Awareness Demonstration of Critical Thinking Demonstration of Being Informed about an Issue Possessing the Requisite Background to Enter the Conversation History Context Grasp Comprehension of Source Material Common Ground Representation |

Cite Sources Works Cited Quotations Paraphrasing Attribution Tag Introduce/Introducing Not Traceable Authority Background Terms Quality of Source Material Quantity of Source Material Type of Source Variety Range of Source Material Conversation Visual Representation of Source Material Demonstration of Methods |

APPENDIX B. The Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education as Corresponding to the IL Criteria Guide for English Composition Researched Arguments (Appendix A)

Process |

Praxis/Enactment |

Engagement |

Attribution |

|

Frame #1: Authority Is Constructed & Contextual |

|||

Frame #2: Information Creation as a Process |

Frame #2: Information Creation as a Process |

||

|

Frame #3: Information Has Value |

|||

|

Frame #4: Research as Inquiry |

|||

Frame #5: Scholarship as Conversation |

|||

|

Frame #6: Searching as Strategic Exploration |

|||

REFERENCES

Artman, M., Frisicaro-Pawlowski, E., & Monge, R. (2010). Not just one shot: Extending the dialogue about information literacy in composition classes. Composition Studies, 38(2), 93—110.

Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2015). Trends in learning outcomes assessment: Key findings from a survey among administrators at AAC&U member institutions. Washington, DC: Hart Research Associates. Retrieved from https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/files/LEAP/2015_Survey_Report3.pdf

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2016). Framework for information literacy for higher education. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Barratt, C. C., Nielsen, K., Desmet, C., & Balthazor, R. (2009). Collaboration is key: Librarians and composition instructors analyze student research and writing. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 9(1), 37—56. Johns Hopkins University Press. Retrieved December 21, 2016, from Project MUSE database.

Bartholomae, D. (1986). Inventing the university. Journal of Basic Writing, 5(1), 4—23. Retrieved from http://wac.colostate.edu/jbw/v5n1/bartholomae.pdf

Behm, N. (2016). Strategic assessment: Using dynamic criteria mapping to actualize institutional mission and build community. In J. Janangelo (Ed.), A critical look at institutional mission: A guide for writing program administration (pp. 40—58). Anderson, SC: Parlor Press.

Belanger, J., Bliquez, R., & Mondal, S. (2012). Developing a collaborative faculty-librarian information literacy assessment project. Library Review, 61(2), 68—91. https://doi.org/10.1108/00242531211220726

Belanger, J., Zou, N., Mills, J. R., Holmes, C., & Oakleaf, M. (2015). Project RAILS: Lessons learned about rubric assessment of information literacy skills. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 15(4), 623—644. Johns Hopkins University Press. Retrieved December 21, 2016, from Project MUSE database.

Broad, B. (2003). What we really value: Beyond rubrics in teaching and assessing writing. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Broad, B., Adler-Kassner, L., Alford, B., Detweiler, J., Estrem, H., Harrington, S., … Weeden, S. (Eds.). (2009). Organic writing assessment: Dynamic criteria mapping in action. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Carter, T. M., & Alderidge, T. (2016). The collision of two lexicons: Librarians, composition instructors and the vocabulary of source evaluation. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 11(1), 23—39.

Council of Writing Program Administrators, National Council of Teachers of English, & National Writing Project. (2011). Framework for success in postsecondary writing. Retrieved from http://wpacouncil.org/files/framework-for-success-postsecondary-writing.pdf

D’Angelo, B., & Maid, B. (2004). Moving beyond definitions: Implementing information literacy across the curriculum. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 30(3), 212—217.

Deitering, A. M., & Jameson, S. (2008). Step by step through the scholarly conversation: A collaborative library/writing faculty project to embed information literacy and promote critical thinking in first year composition at Oregon State University. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 15(1), 57—79. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691310802176830

Gilchrist, D. L. (2009). A twenty year path. Communications In Information Literacy, 3(2), 70—79.

Head, A. J. (2013). Project Information Literacy: What can be learned about the information-seeking behavior of today’s college students? In D. M. Mueller (Ed.), Imagine, innovate, inspire: The proceedings of the ACRL 2013 Conference, April 10—13, 2013, Indianapolis, IN (pp. 472—482). Association of College and Research Libraries. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/2013/papers/Head_Project.pdf

Huot, B. (2002). (Re)articulating writing assessment for teaching and learning. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Janangelo, J., & Adler-Kassner, L. (2009). Common denominators and the ongoing culture of assessment. In M. C. Paretti & K. Powell (Eds.), Assessing writing (pp. 11—34). Tallahassee: Association of Institutional Research Press.

Mazziotti D., & Grettano, T. (2011). “Hanging together”: Collaboration between information literacy and writing programs based on the ACRL Standards and the WPA Outcomes. In D. M. Mueller (Ed.), Declaration of interdependence: The proceedings of the ACRL 2011 Conference, March 30—April 2, 2011, Philadelphia, PA (pp. 180—190). Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/

national/2011/papers/hanging_together.pdf

Oakleaf, M. (2008). Dangers and opportunities: A conceptual map of information literacy assessment approaches. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 8(3), 233—253. Retrieved from Project Muse. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.0.0011