PSAT/NMSQT Prep 2020 - Princeton Review 2020

PSAT reading passage strategies

PSAT reading

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, you will be able to:

· Identify keywords that promote active reading and relate passage text to the questions

· Create short, accurate margin notes that help you research the text efficiently

· Summarize the big picture of the passage

How Much Do You Know?

Directions

In this chapter, you’ll learn how PSAT experts actively read the passage, take notes, and summarize the main idea to prepare themselves to answer all of the passage’s questions quickly and confidently. You saw this kind of reading modeled in the previous chapter. To get ready for the current chapter, take five minutes to actively read the following passage by 1) noting the keywords that indicate the author’s point of view and the passage’s structure, 2) jotting down a quick description next to each paragraph, and 3) summarizing the big picture (the passage’s main idea and the author’s purpose for writing it). When you’re done, compare your work to the sample passage map that follows.

1. This passage is adapted from a 2018 article reviewing the benefits and shortcomings of a financial model called microcredit.

Until a few decades ago, it was virtually impossible for an impoverished person to obtain credit from an institutional source like a bank. Lacking collateral or verifiable income, such people—often citizens of developing nations—simply could not qualify for even a small loan from a traditional financial institution. As a result, these people were unable to start businesses that could free them from the trap of poverty. Some financial experts put forth an intriguing theory: if impoverished people had access to very small loans, called microloans, for the purpose of funding small businesses, they could lift themselves up from poverty to self-employment and perhaps even into a position to employ others. In 1976, an economics professor in Bangladesh extended a microloan of 27 dollars to a group of impoverished village women for the purpose of buying supplies for their business manufacturing bamboo stools. The loan allowed the women to make a modest profit and grow their business to a point of self-sufficiency. Advocates of microlending built on this initial success, maintaining that microcredit was an avenue to widespread entrepreneurship among the poor that could increase individual wealth and, ultimately, reduce poverty. Additionally, since microloans were frequently extended to women borrowers, supporters contended that microfinance was a way to empower women. A variety of microcredit organizations sprang up to serve the needs of the poor in Asia, Latin America, Africa, and Eastern Europe. A number of different microlending business models developed, and over the ensuing decades, the number of customers of microcredit grew from a few hundred to tens of millions worldwide. Microlenders and microcredit advocates told stories of desperately poor people who had lifted themselves out of poverty and into self-sufficiency, and of impoverished women who had become family breadwinners through the use of microloans. Microfinance, it seemed, was a tremendous success. Soon, however, another side of the story came to light. Anecdotes emerged about impoverished borrowers who were unable to pay their interest from their business earnings, became imprisoned in debt, and were forced to sell off their meager possessions to meet their loan obligations. Other stories described customers who used their loans for consumption spending rather than to finance businesses, and who were thus unable either to pay their interest or to return the original money borrowed. A backlash developed against microlending. Members of the media, politicians, and public administrators harshly criticized the industry and its advocates for promoting a process that could harm rather than help the neediest and most vulnerable people. Nevertheless, economists were more cautious. They recognized that anecdotes were not adequate to support either side of the debate meaningfully. What was needed was solid scientific evidence that could quantify the real impacts of microlending. Academics focused on finance and development performed a number of studies exploring various aspects of microfinance. When researchers aggregated the findings of the best of these studies, they concluded that microlending was not the panacea claimed by its advocates. Poverty had not been alleviated on a widescale, or even measurably reduced. Moreover, there was little if any evidence that women had been substantially empowered by microcredit. Perhaps most tellingly, the average incomes of microloan customers had not risen above their previous levels. Critics jumped on these findings, claiming that they proved that microfinance as a whole was a failure. Undeterred, advocates could still point to a variety of less dramatic yet still worthwhile positive outcomes that resulted from microcredit. While borrowers had not increased their incomes on average, they often replaced longer hours of grueling wage-work with more fulfilling and less onerous self-employment. In many cases, temptation spending—expenditures on things like tobacco, alcohol, and gambling—had been reduced in favor of greater savings and expenditures on durable goods, better food, and healthcare. There is also evidence that borrowers’ use of microcredit extended beyond financing small businesses to “income smoothing,” the use of microloans to ease the financial stresses of temporary or seasonal unemployment, crop failures, health crises, and the like. While the original lofty expectations for microfinance were overly optimistic, it would be unfair and inaccurate to classify the practice as a failure. Rather, microfinance should be viewed as a useful tool to help impoverished people better their circumstances, even if only modestly.

2.

Check Your Work

1. Big Picture

Main Idea: Microcredit provides some relief for impoverished people even if it is not the total success its supporters imagined.

Author’s Purpose: To analyze the claims of microcredit advocates and critics in light of research on the subject

o Blurb: The passage will likely define “microcredit” and then analyze its advantages and disadvantages.

o ¶1: The author presents a problem: in the past, impoverished people could not get loans to help them get out of poverty.

o ¶2: The author defines microcredit—very small loans to people in poverty—and presents an example of its early success for women in a small Bangladeshi village.

o ¶3: This paragraph outlines the growth of microcredit. Lenders contended that microloans would build entrepreneurship, especially helping women.

o ¶4: Microcredit lenders grew to the millions and the practice seemed to be very successful. The word “seemed” suggests that the next paragraph will give a counterargument.

o ¶5: The contrast word, “however,” and the phrase “another side of the story” indicate that this paragraph is about the downside of microcredit. The author outlines several negative stories and says the result was a public backlash.

o ¶6: Here’s another contrast (“Nevertheless”): economists didn’t want good or bad stories; they wanted real data and performed studies.

o ¶7: The studies gave three negative results: 1) poverty not alleviated, 2) women not helped, and 3) no increase in average income.

o ¶8: Because of the negative conclusions, critics of microcredit said the whole idea was a failure, but microcredit supporters pointed out several small, good outcomes: 1) reduced hard labor, 2) reduced temptation spending, and 3) better individual crisis management.

o ¶9: Author’s conclusion: microcredit is not a total failure, it can give people in poverty some help.

PSAT Reading Strategies—Keywords, Margin Notes, and the Big Picture Summary

Learning Objectives

After this lesson, you will be able to:

· Identify keywords that promote active reading and relate passage text to the questions

· Create short, accurate margin notes that help you research the text efficiently

· Summarize the big picture of the passage

To read and map a passage like this:

This passage is adapted from an article called “Nature’s Tiny Farmers” that appeared in a popular biology magazine in 2018.

Leafcutter ants are among the most ecologically important animals in the American tropics. At least forty-seven species of leafcutter ants range from as far south as Argentina to as far north as the southern United States. These ants, as their name implies, cut sections of vegetation—leaves, flowers, and grasses—from an array of plants, taking the cut sections back into their underground nests. However, the ants don’t feed on the vegetation they cut; in fact, they’re unable to digest the material directly. Instead, they carry the fragments into dedicated chambers within their nests, where they cultivate a particular species of nutritious fungus on the cut vegetation. It is this fungus that the ants eat and feed to their larvae. Remarkably, each species of leafcutter ant cultivates a different species of fungus, and each of these fungi grows nowhere but within the nests of its own species of leafcutter ant. According to entomologist Ted Schultz of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, “The fungi that [the ants] grow are never found in the wild, they are now totally dependent on the ants.” In other words, over millions of years, the ants have actually domesticated the fungi, much as we humans have domesticated the plants we grow for crops. The leafcutters’ foraging trails extend hundreds of meters throughout the landscape. The ants harvest a wide range of vegetation but are selective, preferring particular plant species and picking younger growth to cut. Research has also shown that the ants often limit how much they cut from a single plant, possibly in response to chemical defenses the cut plant produces. In this way, the amount of damage they cause to individual plants is limited. Leafcutters are probably the most important environmental engineers in the areas they occupy. A single leafcutter nest can extend as far as 21 meters underground, have a central mound 30 meters in diameter with branches extending out to a radius of 80 meters, contain upwards of 1,000 individual chambers, and house up to eight million ants. Where they are present, leafcutters are responsible for up to 25 percent or more of the total consumption of vegetation by all herbivores. Alejandro G. Farji-Brener of Argentina’s National Scientific and Technical Research Council and Mariana Tadey of the National University of Comahue wanted to better understand how the activities of leafcutter ants influence soil conditions. To do so, they analyzed the data from a large number of previous studies to determine how various environmental factors play into the ants’ behavior and their effects on local ecology. The researchers found that overall soil quality and fertility are dramatically higher where leafcutters are present. The ants affect the soil in two ways: first, the physical shifting of the soil that occurs as a consequence of nest construction improves soil porosity, drainage, and aeration; additionally, the ants’ fungus-cultivating activities generate enormous amounts of plant waste, which the ants carry away, either into specialized chambers within the nest or to dedicated refuse piles outside. In fact, this movement of organic matter may be the largest performed by any animal in the environment. This transfer of huge volumes of organic material results in greatly enriched soil, with nutrient levels that are orders of magnitude higher than in areas where the ants are not present. The researchers also determined that seeds germinate more easily and at higher rates in these soils. Additionally, plants grow substantially better in soils that have been modified by leafcutters. In effect, then, the ants create conditions that encourage the growth of plants, thereby greatly improving the conditions of the landscape in general. Furthermore, in areas of disturbance or degradation, such as lands that have been overgrazed or deforested, or those suffering from the effects of fire or drought, leafcutters are major contributors to the natural restoration of healthy plant communities and the overall recovery of the land. The study concludes that “in terms of conservation, ant-nest areas should be especially protected . . . because they are hot spots of plant productivity and diversity.”

|

Relative Nutrient Content of Leafcutter Ant Soils— |

||

|

Nutrient |

Nest Soil: |

Refuse Soil: |

|

Nitrogen |

1.4:1 |

33:1 |

|

Phosphorus |

2.0:1 |

48:1 |

|

Potassium |

1.4:1 |

49:1 |

|

Carbon |

4.2:1 |

47:1 |

|

Calcium |

1.9:1 |

29:1 |

|

Magnesium |

2.2:1 |

15:1 |

You’ll need to know this:

· PSAT Reading passages are preceded by short blurbs that tell you about the author and source of the passage.

· There are three categories of keywords that reveal an author’s purpose and point of view and that unlock the passage’s structure:

o Opinion and Emphasis—words or phrases that signal that the author finds a detail noteworthy (e.g., especially, crucial, important, above all) or has an opinion about it (e.g., fortunately, disappointing, I suggest, it seems likely)

o Connection and Contrast—words or phrases that suggest that a subsequent detail continues the same point (e.g., moreover, in addition, also, further) or that indicate a change in direction or point of difference (e.g., but, yet, despite, on the other hand)

§ In some passages, these keywords may show steps in a process or developments over time (e.g., traditionally, in the past, recently, today, first, second, finally, earlier, since)

o Evidence and Example—words or phrases that indicate an argument (the use of evidence to support a conclusion), either the author’s or someone else’s (e.g., thus, therefore, because), or that introduce an example to clarify or support another point (e.g., for example, such as, to illustrate)

· PSAT experts read strategically, jotting down brief, accurate, and useful margin notes next to each paragraph.

· Expert test takers summarize the passage as a whole by paying attention to its big picture:

o Main Idea—the author’s primary conclusion or overall takeaway

o Author’s Purpose—the author’s reason for writing the passage

§ Express this as a verb (e.g., to explain, to evaluate, to argue, to refute)

Reading Passage and Question Strategy

Why read the passage before reading the questions?

Each PSAT Reading passage is accompanied by 9 or 10 questions. One or two of the questions may ask about the passage as a whole. The others will ask about specific paragraphs, details, or arguments within the passage. PSAT experts use deliberate Reading strategies to answer all of the questions quickly and accurately, with a minimum of rereading.

You’ll need to do this:

The PSAT Reading Passage strategy

· Extract everything you can from the pre-passage blurb

· Read each paragraph actively

· Summarize the passage’s big picture

Extract everything you can from the pre-passage blurb

· Quickly prepare for the passage by unpacking the pre-passage blurb.

o What does the title and date of the original book or article tell you about the author and her purpose for writing?

o What information can you glean from the source (nonfiction book, novel, academic journal, etc.)?

o Is there any other information that provides context for the passage?

Read each paragraph actively

· Note keywords (circling or underlining them may help) and use them to focus your reading on

o the author’s purpose and point of view,

o the relationships between ideas, and

o the illustrations or other support provided for passage claims.

Keywords

Why pay attention to keywords?

Keywords indicate opinions and signal structure that make the difference between correct and incorrect answers on PSAT questions. Consider this question:

With which one of the following statements would the author most likely agree?

o Coffee beans that grow at high altitudes typically produce dark, mellow coffee when brewed.

o Coffee beans that grow at high altitudes typically produce light, acidic coffee when brewed.

To answer that based on a PSAT passage, you will need to know whether the author said:

Type X coffee beans grow at very high altitudes, and so produce a dark, mellow coffee when brewed.

That would make choice (1) correct. But if the author instead said:

Type X coffee beans grow at very high altitudes, but produce a surprisingly dark, mellow coffee when brewed.

Then choice (2) would be correct. The facts in the statements did not change at all, but the correct answer to the PSAT question would be different in each case because of the keywords the author chose to include.

· As you read, jot down brief, accurate margin notes that will help you research questions about specific details, examples, and paragraphs.

o Paraphrase the text (put it into your own words) as you go.

o Ask “What’s the author’s point and purpose?” for each paragraph.

Margin notes

Why jot down notes next to each paragraph?

PSAT Reading is an open-book test. The answer is always in the passage. Margin notes help you zero in on the details and opinions you need to answer questions like these:

As used in line 32, “erased” most nearly means

In the context of the passage as a whole, the question in Lines 72—74primarily functions to help the author

The passage most strongly implies which of the following statements about the Great Recession?

In the third paragraph (lines 52-74), the most likely purpose of the author’s discussion of the “gig economy” is to

Summarize the passage’s big picture

· At the end of the passage, pause for a few seconds to summarize the passage’s big picture to prepare for Global questions. Ask yourself:

o “What is the main idea of the entire passage?”

o “Why did the author write it?”

The Big Picture

Why summarize the passage’s big picture?

Summarizing the big picture prepares you to answer Global questions such as the following:

Which one of the following most accurately expresses the main point of the passage?

The passage primarily serves to

Explanation:

Leafcutter Passage Map

Leafcutter ants are among the most ecologically important animals in the American tropics. At least forty-seven species of leafcutter ants range from as far south as Argentina to as far north as the southern United States. These ants, as their name implies, cut sections of vegetation—leaves, flowers, and grasses—from an array of plants, taking the cut sections back into their underground nests. However, the ants don’t feed on the vegetation they cut; in fact, they’re unable to digest the

leafcutter

ants “farm”

fungus

using cut

vegetation

material directly. Instead, they carry the fragments into dedicated chambers within their nests, where they cultivate a particular species of nutritious fungus on the cut vegetation. It is this fungus that the ants eat and feed to their larvae. Remarkably, each species of

unique

fungus for

each ant

species

leafcutter ant cultivates a different species of fungus, and each of these fungi grows nowhere but within the nests of its own species of leafcutter ant. According to entomologist Ted Schultz of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, “The fungi that [the ants] grow are never found in the wild, they are now totally dependent

ant domesticated

fungus

on the ants.” In other words, over millions of years, the ants have actually domesticated the fungi, much as we humans have domesticated the plants we grow for crops. The leafcutters’ foraging trails extend hundreds of meters throughout the landscape. The ants harvest a wide

ants’ plant

cutting

explained

range of vegetation but are selective, preferring particular plant species and picking younger growth to cut. Research has also shown that the ants often limit how much they cut from a single plant, possibly in response to chemical defenses the cut plant produces. In this way, the amount of damage they cause to individual plants is limited.

why ants

so impt to

environment

Leafcutters are probably the most important environmental engineers in the areas they occupy. A single leafcutter nest can extend as far as 21 meters underground, have a central mound 30 meters in diameter with branches extending out to a radius of 80 meters, contain upwards of 1,000 individual chambers, and house up to eight million ants. Where they are present, leafcutters are responsible for up to 25 percent or more of the total consumption of vegetation by all herbivores. Alejandro G. Farji-Brener of Argentina’s National Scientific and

2 scientists

research

LC ants

Technical Research Council and Mariana Tadey of the National University of Comahue wanted to better understand how the activities of

review prev

studies

leafcutter ants influence soil conditions. To do so, they analyzed the data from a large number of previous studies to determine how various environmental factors play into the ants’ behavior and their effects on local ecology.

findings:

soil better

where LC

ants are

The researchers foundthat overall soil quality and fertility are dramatically higher where leafcutters are present. The ants affect the soil in two ways: first, the physical shifting of the soil that occurs as a

— reason 1

consequence of nest construction improves soil porosity, drainage, and aeration; additionally, the ants’ fungus-cultivating activities generate enormous amounts of plant waste,

— reason 2

which the ants carry away, either into specialized chambers within the nest or to dedicated refuse piles outside.

HUGE

impact

In fact, this movement of organic matter may be the largest performed by any animal in the environment. This transfer of huge volumes of organic material results in greatly enriched soil, with nutrient levels that are orders of magnitude higher than in areas where the ants are not present.

more

findings:

seeds and

plants grow

better

The researchers also determined that seeds germinate more easily and at higher rates in these soils. Additionally, plants grow substantially better in soils that have been modified by leafcutters. In effect, then, the ants create conditions that encourage the growth of plants, thereby greatly improving the conditions of the landscape in general. Furthermore, in areas of disturbance or degradation, such as lands that have been overgrazed or deforested, or those suffering from the effects of fire or drought, leafcutters are major contributors to the natural restoration of healthy plant communities and

recommendation:

protect LC

ant areas

the overall recovery of the land. The study concludes that “in terms of conservation, ant-nest areas should be especially protected . . . because they are hot spots of plant productivity and diversity.”

ANALYSIS

· Pre-passage blurb: The passage was written for a popular biology magazine, so no expertise is expected. The title hints that these ants “cultivate” in some way.

· On the actual PSAT, the pre-passage blurb will always give the author’s name, the title of the book or article from which the passage was adapted, and the year it was published. When necessary, the blurb may also include a context-setting sentence with additional information. Train yourself to unpack the blurb to better anticipate what the passage will cover.

· ¶1: The author emphasizes the leafcutter ant’s value for the environment and explains their name: they cut leaves and grasses and use them to grow the fungi they eat.

· ¶2: Using the opinion keyword “remarkably,” the author writes that each species of leafcutter ant cultivates its own species of fungus, which grows only in that ant species’ nest. Citing an entomologist who says that the fungi are dependent on the ants, the author makes the point that the ants have actually domesticated the fungi, as humans have domesticated crop plants.

· ¶3: The author describes the size of the ants’ harvest areas. They cut a wide variety of vegetation, “but” (contrast keyword) they are selective about what they take and limit the damage they do to individual plants.

· ¶4: The author highlights the ants’ importance as “environmental engineers” by describing the size of their nests and the volume of vegetation they consume in their areas.

· ¶5: The author introduces two researchers who analyzed a large number of earlier studies to investigate how leafcutter ants affect the soil.

· ¶6: The researchers’ findings: leafcutter ants improve soil quality. This occurs “two ways”: 1) physically shifting the soil, and 2) creating plant waste with their fungus cultivation. The author emphasizes that leafcutter ants may be the largest mover of organic matter in their environment.

· ¶7: Another finding from the researchers: soils altered by the ants feature higher rates of seed germination and better-growing plants. The ants help to restore damaged landscapes. Because the ants are so important, the researchers recommend protecting the areas with leafcutter ant nests, noting that they are “hot spots” for plant diversity.

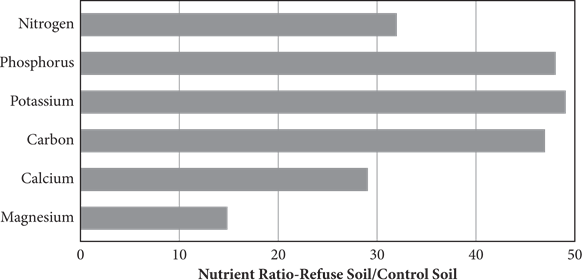

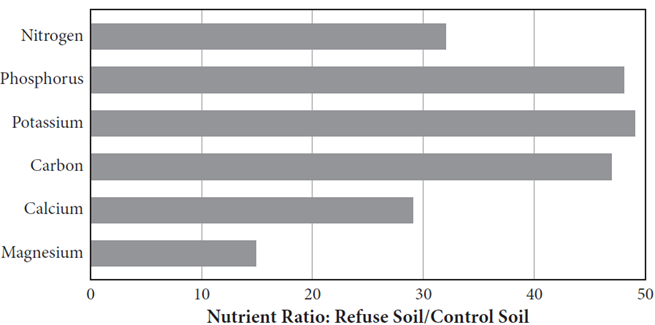

· Graph: The caption indicates that this graph refers to “Nutrient Ratio: Refuse Soil/ Control Soil.” The bars of the graph represent various nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, etc). So, the longer a bar, the more that nutrient is present in refuse soil when compared to control soil.

|

Relative Nutrient Content of Leafcutter Ant Soils— |

||

|

Nutrient |

Nest Soil: |

Refuse Soil: |

|

Nitrogen |

1.4:1 |

33:1 |

|

Phosphorus |

2.0:1 |

48:1 |

|

Potassium |

1.4:1 |

49:1 |

|

Carbon |

4.2:1 |

47:1 |

|

Calcium |

1.9:1 |

29:1 |

|

Magnesium |

2.2:1 |

15:1 |

· Table: The table compares “leafcutter ant” soils to “control” soils (soils that leafcutter ants did not impact). On the left are the ratios of nutrients in nest soil to control soil. All of the nutrients are present in greater amounts in the nest soil than in the control. On the right are the ratios of nutrients in refuse soil to control soil. The nutrients are present in even greater amounts in the refuse soil than in the nest soil. Leafcutter ants increase the amount of these nutrients in their nest soil, and increase it even more in their refuse soil. The rightmost column of the table includes the same data as depicted visually in the graph.

·

charts and graphs in PSAT reading

o What information does the graphic contain?

o Why has the author included the graphic?

o Which paragraph(s) does this information relate to?

o Does the graphic display any trends or relationships that supports a point made in the passage?

In the Reading section, you will not be asked to perform calculations from the data in graphs. You will be asked how they relate to the passage and which claims or arguments they support or refute.

Big Picture

Main Idea: Leafcutter ants are impressive environmental engineers with profound and positive effects on their environments.

Author’s Purpose: To Describe the range, nests, and fungus cultivation of the ants and to summarize the research on how they alter and improve their environments

Now, try another passage on your own. Use the PSAT Reading strategies and tactics you’ve been learning to read and map this passage as quickly and accurately as you can.

Try on Your Own

Directions

Actively read and map the following passage by 1) circling or underlining keywords (from the Emphasis and Opinion, Connection and Contrast, or Evidence and Example categories), 2) jotting down brief, accurate margin notes that reflect good paraphrases of each paragraph, and 3) summing up the big picture. When you’re done, compare your work to that of a PSAT expert in the Answers and Explanations at the end of the chapter.

1. This passage, about the decline of the Norse colonies that once existed in Greenland, is from a comprehensive 2015 research report examining this anthropological mystery.

In 1721, the Norwegian missionary Hans Egede discovered that the two known Norse settlements on Greenland were completely deserted. Ever since, the reasons behind the decline and eventual disappearance of these people have been greatly debated. Greenland, established by the charismatic outlaw Erik the Red in about 986 c.e., was a colony of Norway by 1000 c.e., complete with a church hierarchy and trading community. After several relatively prosperous centuries, the colony had fallen on hard times and was not heard from in Europe, but it wasn’t until Egede’s discovery that the complete downfall of the settlement was confirmed. Throughout the nineteenth century, researchers attributed the demise of the Norse colonies to war between the colonies and Inuit groups. This is based largely on evidence from the work Description of Greenland, written by Norse settler Ivar Bardarson around 1364, which describes strained relationships between the Norse settlers and the Inuits who had recently come to Greenland. However, because there is no archaeological evidence of a war or a massacre, and the extensive body of Inuit oral history tells of no such event, modern scholars give little credence to these theories. New theories about the reason for the decline of the Norse colonies are being proposed partially because the amount of information available is rapidly increasing. Advances in paleoclimatology, for example, have increased the breadth and clarity of our picture of the region. Most notably, recent analyses of the central Greenland ice core, coupled with data obtained from plant material and sea sediments, have indicated severe climate changes in the region that some are now calling a “mini ice age.” Such studies point toward a particularly warm period for Greenland that occurred between the years 800 c.e. and 1300 c.e., which was then followed—unfortunately for those inhabiting even the most temperate portions of the island—by a steady decline in overall temperatures that lasted for nearly 600 years. The rise and fall of the Norse colonies in Greenland, not surprisingly, roughly mirrors this climate-based chronology. Researchers have also found useful data in a most surprising place—fly remains. The insect, not native to the island, was brought over inadvertently on Norse ships. Flies survived in the warm and unsanitary conditions of the Norse dwellings and barns and died out when these were no longer inhabited. By carbon dating the fly remains, researchers have tracked the occupation of the settlements and confirmed that the human population began to decline around 1350 c.e. Changing economic conditions likely also conspired against the settlers. The colonies had founded a moderately successful trading economy based on exporting whale ivory, especially important given their need for the imported wood and iron that were in short supply on the island. Unfortunately, inexpensive and plentiful Asian and African elephant ivory flooded the European market during the fourteenth century, destroying Greenland’s standing in the European economy. At the same time, the trading fleet of the German Hanseatic League supplanted the previously dominant Norwegian shipping fleets. Because the German merchants had little interest in the Norse colonists, Greenland soon found itself visited by fewer and fewer ships each year until its inhabitants were completely isolated by 1480 c.e. Cultural and sociological factors may have also contributed to the demise of the Norse settlements. The Inuit tribes, while recent immigrants to Greenland, had come from nearby areas to the west and had time-tested strategies to cope with the severe environment. The Norse settlers, however, seem to have viewed themselves as fundamentally European and did not adopt Inuit techniques. Inuit apparel, for example, was far more appropriate for the cold, damp environment; the remains from even the last surviving Norse settlements indicate a costume that was undeniably European in design. Likewise, the Norse settlers failed to adopt Inuit hunting techniques and tools, such as the toggle harpoon, which made it possible to capture calorie-rich seal meat. Instead, the Norse relied on the farming styles that had been so successful for their European ancestors, albeit in a radically different climate. It seems likely that this stubborn cultural inflexibility prevented the Norse civilization in Greenland from adapting to increasingly severe environmental and economic conditions.

How Much Have You Learned?

Directions

Take five minutes to actively read the following passage by 1) noting the keywords, 2) jotting down margin notes next to each paragraph, and 3) summarizing the big picture. When you’re done, compare your work to the Answers and Explanations at the end of the chapter.

1.

2. This passage, about infant language acquisition, is adapted from a research paper written in 2017 that explored early childhood development.

Infants are born as scientists, constantly interacting with and questioning the world around them. However, as any good scientist knows, simply making observations is not sufficient; a large part of learning is dependent on being able to communicate ideas, observations, and feelings with others. Though most infants do not produce discernible words until around age one or one-anda- half, they begin gaining proficiency in their native languages long before that. In fact, many linguists agree that a newborn baby’s brain is already preprogrammed for language acquisition, meaning that it’s as natural for a baby to talk as it is for a dog to dig. According to psycholinguist Anne Cutler, an infant’s language acquisition actually begins well before birth. At only one day old, newborns have demonstrated the ability to recognize the voices and rhythms heard during their last trimester in the muffled confines of the womb. In general, infants are more likely to attend to a specific voice stream if they perceive it as more familiar than other streams. Newborns tend to be especially partial to their mother’s voice and her native language, as opposed to another woman or another language. For example, when an infant is presented with a voice stream spoken by his mother and a background stream delivered by an unfamiliar voice, he will effortlessly attend to his mother while ignoring the background stream. Therefore, by using these simple yet important cues, and others like them, infants can easily learn the essential characteristics and rules of their native language. However, it is important to note that an infant’s ability to learn from the nuances of her mother’s speech is predicated upon her ability to separate that speech from the sounds of the dishwasher, the family dog, the bus stopping on the street outside, and, quite possibly, other streams of speech, like a newscaster on the television down the hall or siblings playing in an adjacent room. Infants are better able to accomplish this task when the voice of interest is louder than any of the competing background noises. Conversely, when two voices are of equal amplitude, infants typically demonstrate little preference for one stream over the other. Researchers have hypothesized that because an infant’s ability to selectively pay attention to one voice or sound, even in a mix of others, has not fully developed yet, the infant is actually interpreting competing voice streams that are equally loud as one single stream with unfamiliar patterns and sounds. During the first few months after birth, infants will subconsciously study the language being used around them, taking note of the rhythmic patterns, the sequences of sounds, and the intonation of the language. Newborns will also start to actively process how things like differences in pitch or accented syllables further affect meaning. Interestingly, up until six months of age, they can still recognize and discriminate between the phonemes (single units of sound in a language like “ba” or “pa”) of other languages. Though infants do display a preference for the language they heard in utero, most infants are not biased towards the specific phonemes of that language. This ability to recognize and discriminate between all phonemes comes to an end by the middle of their first year, at which point infants start displaying a preference for phonemes in their native language, culminating at age one, when they stop responding to foreign phonemes altogether. This is part of what is known as the “critical period,” which begins at birth and lasts until puberty. During this period, as the brain continues to grow and change, language acquisition is instinctual, explaining why young children seem to pick up languages so easily.

3.

Reflect

Directions: Take a few minutes to recall what you’ve learned and what you’ve been practicing in this chapter. Consider the following questions, jot down your best answer for each one, and then compare your reflections to the expert responses on the following page. Use your level of confidence to determine what to do next.

Why do PSAT experts note keywords as they read?

What are the three categories of keywords? Provide some examples from each category.

· ________________

o Examples: ________________

· ________________

o Examples: ________________

· ________________

o Examples: ________________

Why do PSAT experts jot down margin notes next to the text?

What are the elements of a strong big picture summary?

Expert Responses

Why do PSAT experts note keywords as they read?

Keywords indicate what the author finds important, express his point of view about the subject and details of the passage, and signal key points in the passage structure. Keywords are the pieces of text that help test takers see which parts of the passage are likely to be mentioned in questions and help the test taker to distinguish between correct and incorrect answer choices about those parts of the passage.

What are the three categories of keywords? Provide some examples from each category.

· Opinion and Emphasis

o Examples: indeed, quite, masterfully, inadequate

· Connection and Contrast

o Examples: furthermore, plus, however, on the contrary

· Evidence and Example

o Examples: consequently, since, for instance, such as

Why do PSAT experts jot down margin notes next to the text?

Margin notes help the test taker research questions that ask about details, examples, and arguments mentioned in the passage by providing a “map” to their location in the text. Margin notes can also help students answer questions about the passage structure and the purpose of a specific paragraph.

What are the elements of a strong big picture summary?

A strong big picture summary prepares a test taker to answer any question about the main idea of the passage or the author’s primary or overall purpose in writing it. After reading the passage, PSAT experts pause to ask, “What’s the main point of the passage?” and “Why did the author write it?”

NEXT STEPS

If you answered most questions correctly in the “How Much Have You Learned?” section, and if your responses to the Reflect questions were similar to those of the PSAT expert, then consider PSAT Reading Passage Strategies an area of strength and move on to the next chapter. Come back to this topic periodically to prevent yourself from getting rusty.

If you don’t yet feel confident, review the material in “PSAT Reading Strategies—Keywords, Margin Notes, and the Big Picture Summary,” then try the exercises you missed again. As always, be sure to review the explanations closely.

Answers and Explanations

Norse Passage Map

This passage, about the decline of the Norse colonies that once existed in Greenland, is from a comprehensive 2015 research report examining this anthropological mystery.

In 1721, the Norwegian missionary

GL colony

gone by

1721—

reasons

debated

Hans Egede discovered that the two known Norse settlements on Greenland were completely deserted. Ever since, the reasons behind the decline and eventual disappearance of these people have been greatly debated. Greenland, established by the charismatic outlaw Erik the Red in about 986 c.e., was a colony of Norway by 1000 c.e., complete with a church hierarchy and trading community. After several relatively prosperous centuries, the colony had fallen on hard times and was not heard from in Europe, but it wasn’t until Egede’s discovery that the complete downfall of the settlement was confirmed.

1800s

researchers

said

cause was

war w/

Inuits

Throughout the nineteenth century, researchers attributed the demise of the Norse colonies to war between the colonies and Inuit groups. This is based largely on evidence from the work Description of Greenland, written by Norse settler Ivar Bardarson around 1364, which describes strained relationships between the Norse settlers

but no arch.

evid.

and the Inuits who had recently come to Greenland. However, because there is no archaeological evidence of a war or a massacre, and the extensive body of Inuit oral history tells of no such event, modern scholars give little credence to these theories. New theories about the reason for the decline of the Norse colonies

much new

info

are being proposed partially because the amount of information available is rapidly increasing. Advances in paleoclimatology, for example, have

climate

data

increased the breadth and clarity of our picture of the region. Most notably, recent analyses of the central Greenland ice core, coupled with data obtained from plant material and sea sediments,

big climate

change

b/4 colony

decline

have indicated severe climate changes in the region that some are now calling a “mini ice age.” Such studies point toward a particularly warm period for Greenland that occurred between the years 800 c.e. and 1300 c.e., which was then followed—unfortunately for those inhabiting even the most temperate portions of the island—by a steady decline in overall temperatures that lasted for nearly 600 years. The rise and fall of the Norse colonies in Greenland, not surprisingly, roughly mirrors this climate-based chronology.

fly remains

Researchers have also found useful data in a most surprising place—fly remains. The insect, not native to the island, was brought over inadvertently on Norse ships. Flies survived in the warm and unsanitary conditions of the Norse dwellings and barns and died out when these were no longer inhabited.

dating

shows

human

decline

—1350

By carbon dating the fly remains, researchers have tracked the occupation of the settlements and confirmed that the human population began to decline around 1350 c.e.

econ problems,

too

Changing economic conditions likely also conspired against the settlers. The colonies had founded a moderately successful trading economy based on exporting whale ivory,

ivory

market ↓

especially important given their need for the imported wood and iron that were in short supply on the island. Unfortunately, inexpensive and plentiful Asian and African elephant ivory flooded the European market during the fourteenth century, destroying Greenland’s standing in the European economy. At the same time, the trading fleet of the German Hanseatic League supplanted the previously dominant

+ German

traders

didn’t visit

GL

Norwegian shipping fleets. Because the German merchants had little interest in the Norse colonists, Greenland soon found itself visited by fewer and fewer ships each year until its inhabitants were completely isolated by 1480 c.e.

also

cultural

factors

Cultural and sociological factors may have also contributed to the demise of the Norse settlements. The Inuit tribes, while recent immigrants to Greenland, had come from nearby areas to the west and had time-tested strategies to cope with the severe environment. The Norse settlers, however, seem to have viewed themselves as fundamentally European and did not adopt Inuit techniques. Inuit apparel, for example, was far more appropriate for the cold, damp environment; the remains

Euro.

clothes

from even the last surviving Norse settlements indicate a costume that was undeniably European in design. Likewise, the Norse settlers failed to adopt Inuit hunting techniques and tools, such as the toggle harpoon, which

hunting vs.

farming

made it possible to capture calorie-rich seal meat. Instead, the Norse relied on the farming styles that had been so successful for their European ancestors, albeit in a radically different climate. It seems likely that this stubborn cultural inflexibility prevented the Norse civilization in Greenland from adapting to increasingly severe environmental and economic conditions.

ANALYSIS

· Pre-passage blurb: The topic of the passage is the “anthropological mystery” of Norse colonies in Greenland that disappeared. The passage is based on a 2015 research report, so there are likely to be many factual details.

· ¶1: The writer provides background on the existence of the Norse settlements in Greenland. In the 1700s, a missionary discovered that settlements had been deserted. The settlements’ decline is a matter of debate—and given the pre-passage blurb, it is reasonable to predict that the rest of the passage will address this debate.

· ¶2: Nineteenth-century researchers relied on an account by a Norse settler to conclude that the decline was caused by war between Norse and Inuit people. The writer’s use of the contrast keyword “however” signals a problem with this theory: modern scholars reject it due to a lack of evidence from archaeology or Inuit oral history. Expect to learn more about the modern theories next.

· ¶3: New information is driving new theories. The writer uses example keywords (“for example”) to introduce evidence from paleoclimatology, which indicates that a “mini ice age” corresponded with the fall of the Norse in Greenland. In addition, carbon dating of flies—which the Norse brought to Greenland—helps to confirm when the colonies began to decline.

· ¶4: The writer describes an additional theory: economic conditions hurt the settlers. Their trade in whale ivory became less profitable as elephant ivory reached European markets, and the rise of German merchants meant that fewer ships visited the Greenland colonies.

· ¶5: One further theory is that Norse culture may not have adapted properly to Greenland. The writer compares the Inuit and the Norse, using the examples of clothing, hunting, and farming. While the Inuit (native to the Arctic) had tools and practices suited to the environment, the Norse (in the author’s opinion, “stubborn[ly]”) maintained European techniques inappropriate to Greenland.

Big Picture

Main Idea: New information shows that factors such as climate, economy, and culture may have caused the collapse of the Norse colonies in Greenland.

Author’s Purpose: To describe current theories (and evidence for them) of what happened to the Norse in Greenland

Infant Language Passage Map

This passage, about infant language acquisition, is adapted from a research paper written in 2017 that explored early childhood development.

1. Infants are born as scientists, constantly interacting with and questioning the world around them. However, as any good scientist knows, simply making observations

babies

start

learning

lang. b/4

they can

talk

is not sufficient; a large part of learning is dependent on being able to communicate ideas, observations, and feelings with others. Though most infants do not produce discernible words until around age one or one-anda- half, they begin gaining proficiency in their native languages long before that. In fact, many linguists agree that a

“pre-programmed”

newborn baby’s brain is already preprogrammed for language acquisition, meaning that it’s as natural for a baby to talk as it is for a dog to dig.

Cutler:

learn lang.

b/4 birth

According to psycholinguist Anne Cutler, an infant’s language acquisition actually begins well before birth. At only one day old, newborns have demonstrated the ability to recognize the voices and rhythms heard during their last trimester in the muffled confines of the womb. In general, infants are more likely to attend to a specific voice stream if they perceive it as more familiar than other streams. Newborns tend to be especially

—support

partial to their mother’s voice and her native language, as opposed to another woman or another language. For example, when an infant is presented with a voice stream spoken by his mother and a background stream delivered by an unfamiliar voice, he will effortlessly attend to his mother while ignoring the background stream. Therefore, by using these simple yet important cues, and others like them, infants can easily learn the essential characteristics and rules of their native language. However, it is important to note that an infant’s ability to learn from the nuances of her mother’s speech is predicated upon her ability to separate

need

mom’s

voice sep.

from bkgd

that speech from the sounds of the dishwasher, the family dog, the bus stopping on the street outside, and, quite possibly, other streams of speech, like a newscaster on the television down the hall or siblings playing in an adjacent room. Infants are better

+ louder

than

other

voices

able to accomplish this task when the voice of interest is louder than any of the competing background noises. Conversely, when two voices are of equal amplitude, infants typically demonstrate little preference for one stream over the other. Researchers have hypothesized that because an infant’s ability to selectively pay attention to one voice or sound, even in a mix of others, has not fully developed yet, the infant is actually interpreting competing voice streams that are equally loud as one single stream with unfamiliar patterns and sounds. During the first few months after birth, infants will subconsciously

newborns

learn

patterns

study the language being used around them, taking note of the rhythmic patterns, the sequences of sounds, and the intonation of the language. Newborns will also start to actively process how things like differences in pitch or accented syllables further

<6 mos.:

“hear”

other

lang. too

affect meaning. Interestingly, up until six months of age, they can still recognize and discriminate between the phonemes (single units of sound in a language like “ba” or “pa”) of other languages. Though infants do display a preference for the language they heard in utero, most infants are not biased towards the specific phonemes of that language.

~1 yr.:

prefer

their own

lang.

This ability to recognize and discriminate between all phonemes comes to an end by the middle of their first year, at which point infants start displaying a preference for phonemes in their native language, culminating at age one, when they stop responding to foreign phonemes altogether. This is part of what is known as the “critical

crit. pd.:

still easier

to learn

other

lang.

period,” which begins at birth and lasts until puberty. During this period, as the brain continues to grow and change, language acquisition is instinctual, explaining why young children seem to pick up languages so easily.

ANALYSIS

· Pre-passage blurb: The passage is from a research text about “infant language acquisition.” It will likely be a factual, academic review of ideas and theories.

· ¶1: Using a couple of similes to make her point, the author states a central thesis: infants begin learning their native language well before they can produce words. She states that linguists consider babies “pre-programmed for language acquisition.” The following paragraphs will elaborate on and support this thesis.

· ¶2: The first elaboration comes from psycholinguist Anne Culter: infants start acquiring language before birth. The rest of the paragraph supports this claim. Newborns immediately recognize familiar voices, preferring their mother’s voice and easily attending to it instead of others. This helps the infant learn his or her native tongue.

· ¶3: The author explains some limiting factors (note the opening contrast keyword, “however”) for infant language acquisition. Babies can learn from their mother’s speech only if they can separate that speech from background noise. They are better at focusing on their mother’s voice when the mother’s voice is louder than other sounds. Research indicates that they cannot interpret different voices of equal volume separately.

· ¶4: The author explains how infants start learning their native language. They subconsciously study patterns, sounds, and intonation, and start to connect sound to meaning. The author emphasizes (with “[i]nterestingly”) that, up to six months old, babies can distinguish between the sounds in unfamiliar languages, not only the language they were exposed to in the womb.

· ¶5: The author continues along the development timeline. By age one, infants prefer their own language’s sounds (and stop responding to other languages’ sounds). Still, it’s easier to learn foreign languages (it’s still “instinctual,” says the author) up through puberty because the brain is still growing and changing.

Big Picture

Main Idea: Infants listen to voices in their environments to acquire language instinctually, possibly starting before they are even born.

Author’s Purpose: To explain the abilities and limitations of infants in acquiring language